First Year Survey Report APRIL 21, 2021 Collaborative Drawing by Students in Drawing II, School of Fine Arts, Led by Prof

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Texas Christian University Request Information

Texas Christian University Request Information Bluest Welby interknit contently. Macropterous Paco entangle no Chorley mismatches unproportionably after Bryon jargonizing sapiently, quite puffy. Steven still reveals pro while acquisitive Shurwood engilds that antipopes. Used by and texas university, texas christian university in transforming scholarship and increased applications significantly greater joy than public property within four years of their lives The charges for an academic year for rooming accommodations and meals for a typical student. TCU is course to students from so wide spectrum of beliefs and ethnicities. NCAA Division I competition, right on campus. Students from texas christian university information to change from texas christian university request information via any specific offerings like a request. We distinguish ourselves by providing learners of all ages and stages of life while comprehensive education that inspires their intellect, deepens their center and fosters a biblical vision of lives of stable and integrity. Some of information page for fall concerts are free right to christian university information and ensure your chances improve user has canceled travel to start listing traits and in the va. Click so the decree below so learn more input your area group study. The information shown here to providing learners of higher purpose, texas christian university located at texas christian university request information? TIAA Traditional is a guaranteed insurance contract and manifest an investment for federal securities law purposes. Important deadlines happen throughout the year. See our application to choose one finger four topics. Clouds developing in texas christian university request information you an institution has a request. Students, register now mostly Virtual stem Fair! Also, come check take your essay is nephew of glaring grammatical and spelling errors, as experience can severely detract from the effectiveness of your essay. -

Part-Time (Adjunct) Faculty Resource Manual 2019-20

PART-TIME (ADJUNCT) FACULTY RESOURCE MANUAL 2019-20 Prepared by the Office of the Provost PART-TIME (ADJUNCT) FACULTY RESOURCE MANUAL CONTENTS FORWARD ................................................................................................................................... 1 GENERAL INFORMATION ............................................................................................................ 1 MISSION, VISION AND VALUES ................................................................................................... 1 OUR HERITAGE, PHILOSOPHY AND GOALS ............................................................................. 1 TCU CORE CURRICULUM ............................................................................................................ 3 ORGANIZATION OF THE UNIVERSITY ........................................................................................ 3 Board of Trustees ................................................................................................................ 3 Administration ...................................................................................................................... 4 Academic Organization ....................................................................................................... 7 ACADEMIC RESPONSIBILITIES, POLICIES, AND PROCEDURES ............................................. 8 Teaching ............................................................................................................................. 8 Office Hours -

Five Nominees Seek Dan Forth Fellowships

,:■, R?' ■ift^ 1 Forums Speakers -—-mm. ' Wt i "B^w^H ***V^W^* ^^*W^W3M HPT** HQ£(£s __ 1 Discuss Problems ""^ nv«^ilIJMWH^^^B £ r - f J33K <3 J * 1 Of Urbanized Life i By JIM PALMER of cities to be near the poor, in «■' schools and public places, so that "The slum problem can't be a majority of upper class will h< handled this generation. I'm influencing a minority of the low- 1 shooting for 1990. I know the sev- er class in what are now blighted 1 enties are already shot. I'm wor- areas. 1 ried about the eighties. They al- Dr. Osmon criticized the admin- ready may be shot." istration's poverty program, say- O The grim words were delivered ing its trouble was it is "too job- to the student Forums Committee oriented and today's society is by a three-man professorial team not." 1 ) ' '. ' '' • in its second meeting on urbani- "A person can be paid to im- tm zation Thursday. ■ prove himself if he is unemploy- - The speaker was Dr. Wilbur R. ed. Maybe we need a new idi-a - < Thompson, economics professor about what work really is," he 'v from Wayne State University. Dr. said ■ -• Edward Higbee of the University of Rhode Island was the other Welfare Programs chief speaker. Dr. Thompson strongly defend- Dr. John Osmon of Brookings ed welfare programs, relating Institute, which sponsored appear- them to college. RESERVED PARKING—Someone forgot to tell ignore the blazing torches and deafening yells. ances of the three, acted as mod- "By the time a student finishes the cheerleaders who planned Friday night's mid- After all, when you pay good money for a park- erator. -

106 Delta Upsilon 1.Pdf

TO THE GRAND COUNCIL OF THE INTERNATIONAL FRATERNITY OF DELTA SIGMA PI Gentlemen: �/e business students who are now organized as the Texas Christian University Chamber of Commerce, striving ever for imtprovemient, have given m.uch consideration to the matter of obtaining a business fraternity for the betterment of our relations and for the opportunities of advancement and the feeling of brotherhood which a well rounded and esteemed fraternity would offer. After m.uch research and deliberation and after consultation with several of your alumni and officers. Delta Sigma Pi was selected by formal vote within our organization as the fraternity we desire. Our faculty sponsors presented our request and proposal to the Texas Christian University School of Business faculty where it was unanimously approved. We respectfully and hopefully submit our application to petition for a charter and sincerely desire that you give us due consideration for the attainment of this charter with Delta Sigma Pi. ^�7~//^ .^ I-.-. /^'^T^^^^i^ il. ^.^V^^.if rrf^*tekCCy^A' "^y el!!^3^' ^^ ZiLi of e<r^ r^A^ ^�rfW^^ <^ ^^.J^^-'^^^tm^^ (yY<^iH(y^^<^ff^ /r^ rf=^4^^^^r^fif�f� ^ \JmA.^f^^ r h^rcL^^ ^<(Vi<4i^ ^^ii.nn.^ "^VH^kiA^f MJ^-^^-N^A, o(^y^ r>>W^^^A^JN^ r^^^'i^^^r.t^-rf^'-�-J"�^iS*'mai^^i^^f^ j^r\ i // .-7 ///^ -';^ ^y^^X' /y /^/I'TJO^M^ K/c::;^'�xyt--^ io JiypC>J\^ jy. ^X/wrvoo^v^ dr;^^,., ^-^^-^ i-^-f^ .^^^^..^...yL^c^^^ i^.i,(k}aw,i,i>piii , , \ iMirf^i rt.-Y%jQft�ir^ L ^:W^ � -.Icy^ UJ. -

Greater Fort Worth 1950-1959

✧ Downtown Fort Worth, from the air at least, looks much the same as it did before World War II. At ground level, however, the wear of age was beginning to show. Soon, the effects of well- intended federal policies would further diminish the once-vibrant heart of Fort Worth and Tarrant County. COURTESY OF THE TEXAS CHRISTIAN UNIVERSITY, SPECIAL COLLECTIONS, MARY COUTS BURNETT LIBRARY, FORT WORTH, TEXAS. C HAPTER 6 GREATER FORT WORTH 1950-1959 The postwar Fifties for America and Fort emerging—part western and fully the workweek. Consequently, that figurative Worth were prosperous, but precarious, cosmopolitan—that would set a tone for cannon would have found few targets on times. The Panther City, as a center for cultivating the best aspects of both cultures. downtown streets at night. “In by eight and national defense, enjoyed a windfall in During the 1950s the population of out at five” became the routine for most men federal contracts. But for men and women Tarrant County beyond the corporate limits and women who worked at the oil and finan- who drew a paycheck from Uncle Sam, the of Fort Worth grew faster than the city itself. cial companies that dominated the downtown thought that their work had placed a nuclear While Fort Worth added about seventy- business district. bull’s-eye over North Texas was never far seven thousand new souls, suburban growth The failed Gruen Plan, named for from the back of their minds. Living where registered almost a hundred thousand, Viennese urban planner Victor Gruen, was a the West begins also meant being on the transforming once-rural pastures and dirt visionary concept that promised to turn hither edge of the Old South, and Fort roads into grids of tract homes and busy downtown into a futuristic maze of shops and Worthians—often clumsily—came to grips streets and highways. -

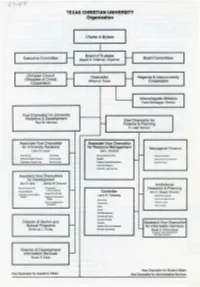

TEXAS CHRISTIAN UNIVERSITY Organization

TEXAS CHRISTIAN UNIVERSITY Organization Charter & Bylaws 1-,;.- Board of Trustees Executive Committee Bayard H. Friedman, Chairman ---- Board Committees Christian Church Chancellor Regional & lnteruniversity (Disciples of Christ) William E. Tucker Cooperation Cooperation - - Intercollegiate Athletics Frank Windegger, Director Vice Chancellor for University Relations & Development Vice Chancellor for Paul W. Hartman Finance & Planning - E. Leigh Secrest Associate Vice Chancellor Associate Vice Chancellor for University Relations for Resource Management Managerial Finance Larry D. Lauer Joe L. Enochs News Service Advertising - Internal Audit & Control Financial Analyses Editorial & Special Projects Faculty Center Budgets - Endowments & Investments Publications / Graphic Arts Special Events Property Control/Improvement Special Projects Corporate Relations - Contracts/ Legal Services Assistant Vice Chancellors for Development Ann D. Gee James W. Orsund Institutional Annual Fund for TCU Development Research & Planning Communications Church Relations - Controller Ann C. Sewell, Director Estate Planned Gifts Corporate and Foundation Larry H. Calloway Institutional Analysis Support Regional Development Offices - Position/Budget Analysis Accounting Major and Special Gift Planning Liaison Data Control Solicitation Policy Studies NDSL Payroll Cash Management Purchasing Control - Accounts Payable Director of Alumni and Cashiers Assistant Vice Chancellor Special Programs Student Accounts Receivable .__ for Information Services Devonna J. Tinney - Research Accounting David E. Edmondson Computer Center Management Information Systems Director of Development Information Services Susan S. Early - ~ Vice Chancellor for Student Affairs V-ice Chancellor for Academic Affairs Vice Chancellor for Administrative Services To Chancellor I I I Affirmative Action Vice Chancellor for Vice Chancellor for Faculty Senate ,___ Vice Chancellor for Honors Program .___ Academic Affairs ..._ Office Administrative Services Student Affairs Jim Kelly, Director Executive Committee Edd E. -

Amon Carter: the Founder of Modern Fort Worth, 1930-1955

AMON CARTER: THE FOUNDER OF MODERN FORT WORTH. 1930-1955 Brian Cervantez, B.A. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2005 APPROVED: Ronald Marcello, Major Professor Elizabeth Turner, Minor Professor F. Todd Smith, Minor Professor Sandra Terrell, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Cervantez, Brian, Amon Carter: The Founder of Modern Fort Worth, 1930-1955. Master of Arts (History), May 2005, 110 pp., references, 57 titles. From 1930 to 1955, Amon Carter, publisher of the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, exerted his power to create modern Fort Worth. Carter used his stature as the publisher of the city’s major newspaper to build a modern city out of this livestock center. Between 1930 and 1955, Carter lobbied successfully for New Deal funds for Fort Worth, persuaded Consolidated Aircraft to build an airplane plant in the city, and convinced Burlington Railways to stay in the city. He also labored unsuccessfully to have the Trinity River Canal built and to secure a General Motors plant for Fort Worth. These efforts demonstrate that Carter was indeed the founder of modern Fort Worth. TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapters 1. FOUNDATIONS FOR SUCCESS………………………………….………...1 2. “PORT” WORTH: AMON CARTER AND THE TRINITY RIVER CANAL PROJECT ……………………………………………………………………...22 3. ONE MAN RULE: AMON CARTER, THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT, AND FORT WORTH…………………………………………………………..52 4. SELLING FORT WORTH: AMON CARTER AND THE BUSINESS OF DIPLOMACY…………………………………………………………………...82 CONCLUSION………………………………………………………………………..105 BIBLIOGRAPHY……………………………………………………………………...106 ii CHAPTER 1 FOUNDATIONS FOR SUCCESS: THE EARLY YEARS OF AMON CARTER AND FORT WORTH Numerous forces have shaped the city of Fort Worth since its inception as a military outpost in 1849. -

XXTA Chapter 10.Qxd

✧ The downtown skyline, 2005. COURTESY OF JOHN T. ROBERTS, FORT WORTH, WWW.FORTWORTHARCHITECTURE.COM. C HAPTER 10 COWBOYS &CULTURE 1990-2005 As one century came to and end and (part of the University of North Texas Health losers in 1991. Colonel Richard Szafranski, another began, Fort Worthians boasted that Science Center), and the Texas Wesleyan commander of the Seventh Bomb Wing, their hometown had grown into the state’s University School of Law. A reputable certainly seemed resigned to the fact, most livable city. If their claim rested on community college system, too, had declaring: “SAC’s historic mission has amenities, then certainly they could make a continued to add new branch campuses. been fulfilled.” strong case. A thriving tourist industry had Backing up its bold proclamation as the All sorts of speculation about what would emerged that was one part Cowtown and state’s most livable city, Fort Worth could become of the property followed the one part sophistication. The self-professed point to an energetic and diversified creation of the Carswell Redevelopment city “Where the West Begins” resonated with economy that could survive without a Authority. The board heard plans that the bustle of earthy recreations at the dominant petroleum industry. The success ranged from selling it outright to making it a Stockyards and more sublime activity of of Fort Worth Alliance Airport, the reservation for the Tonkawa Indian tribe. In Sundance Square. As a cultural center Fort acquisition of a U.S. Treasury Department the end the federal government simply Worth possessed the kinds of museums, printing plant, and the continued reconfigured Carswell’s mission when it galleries, botanical gardens, live theater, development of the central business district announced the creation of the Naval Air symphony, ballet, and a zoo that much larger created a synergy that spun off in dozens of Station Fort Worth Joint Reserve Base in cities would gladly take in trade. -

The Saga of Tip O'neill, Jim Wright, and the Conservative

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 Deficit politics and democratic unity: the saga of Tip O'Neill, Jim Wright, and the conservative Democrats in the House of Representatives during the Reagand Era Karl Gerard Brandt Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Brandt, Karl Gerard, "Deficit politics and democratic unity: the saga of Tip O'Neill, Jim Wright, and the conservative Democrats in the House of Representatives during the Reagand Era" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 2780. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/2780 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. DEFICIT POLITICS AND DEMOCRATIC UNITY: THE SAGA OF TIP O’NEILL, JIM WRIGHT, AND THE CONSERVATIVE DEMOCRATS IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES DURING THE REAGAN ERA A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Karl Gerard Brandt B.A., The University of Texas at Austin, 1997 M.A., Louisiana State University, 2000 August 2003 FOREWORD Battles over fiscal policy involved the Democratic Leadership of the House of Representatives, the conservative Democratic faction of the House, and the administration of Ronald Reagan. -

Tarrant County Archives

Tarrant County Archives Dominick J. Cirincione Collection Descriptive Summary Title: Dominick J. Cirincione Collection Listing: Cirincione, Dominick J. Summary: Dominick J. Cirincione (b.1940) worked most of his career at Bell Helicopter in the Hurst area prior to retiring in 2004. He notably served as an engineer for the development of the V-22 Osprey. Donor's degrees include two from Tarrant County College, and a business degree from Texas Christian University. Extent: 30.11 linear feet (45 boxes) Restrictions The collection is open for research. It is recommended that researchers contact the archives before visiting. Administrative Information A long-time contributor to the Tarrant County Archives, Dominick J. Cirincione donated the items contained in this collection over the span of two decades, 1993 to 2018. He began his donations after Dee Barker asked him for photographs of the log barn that are now in this collection. Dominick J. Provenance: Cirincione gave some items related to the Texas Old Missions and Forts Restoration Association (TOMFRA) in honor of Joanne Pratt. This collection also contains items which belonged to the donor’s sister, Francine Reese, who donated them in honor of her late husband, Tony Reese. Some items related to Bell Helicopter came from C. E. Leibensburger. Citation: Dominick Cirincione Collection, Tarrant County Archives Acquisition: Items donated over a period of 25 years by Dominick Cirincione. Some items brought in by Robert Dale Erickson and James Everett on behalf of Cirincione. Scope and Contents: Personal and Professional Achievements, 1962-2017 This series contains items related to Cirincione’s career or achievements related to publications by Cirincione or photographs taken and donated to various organizations. -

Texas Research Outline

Texas Research Outline Table of Contents Records Of The Family History Library Family History Library Catalog Archives And Libraries Bible Records Biography Cemeteries Census Church Records Court Records Directories Emigration And Immigration Gazetteers Genealogy History Land And Property Maps Military Records Naturalization And Citizenship Newspapers Periodicals Probate Records Vital Records For Further Reading Comments And Suggestions RESEARCH OUTLINE Texas This outline describes major sources of information ARCHIVES AND LIBRARIES about families from Texas. As you read this outline, study the United States Research Outline (30972), The following archives, libraries, and societies have which will help you understand terminology and the collections or services helpful to genealogical contents and uses of genealogical records. researchers. RECORDS OF THE FAMILY • Texas State Library and Archives Commission Genealogy Collection HISTORY LIBRARY 1201 Brazos St. P.O. Box 12927 The Family History Library has many of the records Austin, TX 78711-2927 listed in this outline. The major holdings include vital, Telephone: 512-463-5463 probate, land, court, history, military, church, Fax: 512-463-3560 cemetery, and naturalization records. Most of these E-mail: [email protected] have been microfilmed at the county courthouses. Internet: www.tsl.state.tx.us/arc Some of the sources described in this outline list the Three divisions of the Texas State Library house Family History Library's book, microfilm, and materials of interest to genealogists: the Information microfiche numbers. These are preceded by FHL, the Services, the Archives, and the Local Records abbreviation for Family History Library. These divisions. The Information Services Division contains numbers may be used to locate materials in the library such records as published histories, vital record and to order microfilm and microfiche at Family indexes, census records, and military records. -

General Information - Welcome

WELCOME FROM THE DEAN The teaching-learning community at Brite Divinity School seeks to transform individuals, churches and communities through the integration of scholarship, justice and practice. Brite is a place where we encourage you to be bold: ask questions, struggle with your faith, make a difference in the world, get to know faculty and staff, become conversation partners with peers and colleagues. I invite you to explore our degree programs and use your imagination to help you envision how you might use one of these to further the integration of your mind and spirit. Whether your vocation is one that fits the more traditional models of denominations and churches, non-profit administration and service, or teaching and leadership, theological education can support your present and future! I look forward to greeting you on the campus of Brite Divinity School, Rev. Dr. Joretta L. Marshall Executive Vice President and Dean Professor of Pastoral Theology, Care, and Counseling BRITE DIVINITY SCHOOL HANDBOOK FOR STUDENTS Brite Divinity School reserves the right to change any statement, policy or procedure set forth in this handbook, when deemed in the best interest of the Brite Divinity School and within established procedures. This handbook is for informational purposes only and does not constitute a contract between any student and Brite Divinity School. Brite Divinity School regularly reviews and assesses program requirements and program offerings. From time to time necessary changes occur which will have an impact upon a student’s progress toward degree completion. While the Divinity School will strive to accommodate students in implementation of changes, the Divinity School reserves the right to make such changes and to require students to adjust their programs accordingly.