The Saga of Tip O'neill, Jim Wright, and the Conservative

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Monica Prasad Northwestern University Department of Sociology

SPRING 2016 NEW YORK UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF LAW COLLOQUIUM ON TAX POLICY AND PUBLIC FINANCE “The Popular Origins of Neoliberalism in the Reagan Tax Cut of 1981” Monica Prasad Northwestern University Department of Sociology May 3, 2016 Vanderbilt-208 Time: 4:00-5:50 pm Number 14 SCHEDULE FOR 2016 NYU TAX POLICY COLLOQUIUM (All sessions meet on Tuesdays from 4-5:50 pm in Vanderbilt 208, NYU Law School) 1. January 19 – Eric Talley, Columbia Law School. “Corporate Inversions and the unbundling of Regulatory Competition.” 2. January 26 – Michael Simkovic, Seton Hall Law School. “The Knowledge Tax.” 3. February 2 – Lucy Martin, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Department of Political Science. “The Structure of American Income Tax Policy Preferences.” 4. February 9 – Donald Marron, Urban Institute. “Should Governments Tax Unhealthy Foods and Drinks?" 5. February 23 – Reuven S. Avi-Yonah, University of Michigan Law School. “Evaluating BEPS” 6. March 1 – Kevin Markle, University of Iowa Business School. “The Effect of Financial Constraints on Income Shifting by U.S. Multinationals.” 7. March 8 – Theodore P. Seto, Loyola Law School, Los Angeles. “Preference-Shifting and the Non-Falsifiability of Optimal Tax Theory.” 8. March 22 – James Kwak, University of Connecticut School of Law. “Reducing Inequality With a Retrospective Tax on Capital.” 9. March 29 – Miranda Stewart, The Australian National University. “Transnational Tax Law: Fiction or Reality, Future or Now?” 10. April 5 – Richard Prisinzano, U.S. Treasury Department, and Danny Yagan, University of California at Berkeley Economics Department, et al. “Business In The United States: Who Owns It And How Much Tax Do They Pay?” 11. -

Women in the United States Congress: 1917-2012

Women in the United States Congress: 1917-2012 Jennifer E. Manning Information Research Specialist Colleen J. Shogan Deputy Director and Senior Specialist November 26, 2012 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RL30261 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Women in the United States Congress: 1917-2012 Summary Ninety-four women currently serve in the 112th Congress: 77 in the House (53 Democrats and 24 Republicans) and 17 in the Senate (12 Democrats and 5 Republicans). Ninety-two women were initially sworn in to the 112th Congress, two women Democratic House Members have since resigned, and four others have been elected. This number (94) is lower than the record number of 95 women who were initially elected to the 111th Congress. The first woman elected to Congress was Representative Jeannette Rankin (R-MT, 1917-1919, 1941-1943). The first woman to serve in the Senate was Rebecca Latimer Felton (D-GA). She was appointed in 1922 and served for only one day. A total of 278 women have served in Congress, 178 Democrats and 100 Republicans. Of these women, 239 (153 Democrats, 86 Republicans) have served only in the House of Representatives; 31 (19 Democrats, 12 Republicans) have served only in the Senate; and 8 (6 Democrats, 2 Republicans) have served in both houses. These figures include one non-voting Delegate each from Guam, Hawaii, the District of Columbia, and the U.S. Virgin Islands. Currently serving Senator Barbara Mikulski (D-MD) holds the record for length of service by a woman in Congress with 35 years (10 of which were spent in the House). -

1990 NGA Annual Meeting

BARLOW & JONES P.O. BOX 160612 MOBILE, ALABAMA 36616 (205) 476-0685 ~ 1 2 ACHIEVING EDUCATIONAL EXCELLENCE 3 AND ENVIRONMENTAL QUALITY 4 5 National Governors' Association 6 82nd Annual Meeting Mobile, Alabama 7 July 29-31, 1990 8 9 10 11 12 ~ 13 ..- 14 15 16 PROCEEDINGS of the Opening Plenary Session of the 17 National Governors' Association 82nd Annual Meeting, 18 held at the Mobile Civic Center, Mobile, Alabama, 19 on the 29th day of July, 1990, commencing at 20 approximately 12:45 o'clock, p.m. 21 22 23 ".~' BARLOW & JONES P.O. BOX 160612 MOBILE. ALABAMA 36616 (205) 476-0685 1 I N D E X 2 3 Announcements Governor Branstad 4 Page 4 5 6 Welcoming Remarks Governor Hunt 7 Page 6 8 9 Opening Remarks Governor Branstad 10 Page 7 11 12 Overview of the Report of the Task Force on Solid Waste Management 13 Governor Casey Governor Martinez Page 11 Page 15 14 15 Integrated Waste Management: 16 Meeting the Challenge Mr. William D. Ruckelshaus 17 Page 18 18 Questions and Discussion 19 Page 35 20 21 22 23 2 BARLOW & JONES P.O. BOX 160612 MOBILE, ALABAMA 36616 (205) 476-0685 1 I N D E X (cont'd) 2 Global Environmental Challenges 3 and the Role of the World Bank Mr. Barber B. Conable, Jr. 4 Page 52 5 Questions and Discussion 6 Page 67 7 8 Recognition of NGA Distinguished Service Award Winners 9 Governor Branstad Page 76 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 3 BARLOW & JONES P.O. -

Appendix File Anes 1988‐1992 Merged Senate File

Version 03 Codebook ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ CODEBOOK APPENDIX FILE ANES 1988‐1992 MERGED SENATE FILE USER NOTE: Much of his file has been converted to electronic format via OCR scanning. As a result, the user is advised that some errors in character recognition may have resulted within the text. MASTER CODES: The following master codes follow in this order: PARTY‐CANDIDATE MASTER CODE CAMPAIGN ISSUES MASTER CODES CONGRESSIONAL LEADERSHIP CODE ELECTIVE OFFICE CODE RELIGIOUS PREFERENCE MASTER CODE SENATOR NAMES CODES CAMPAIGN MANAGERS AND POLLSTERS CAMPAIGN CONTENT CODES HOUSE CANDIDATES CANDIDATE CODES >> VII. MASTER CODES ‐ Survey Variables >> VII.A. Party/Candidate ('Likes/Dislikes') ? PARTY‐CANDIDATE MASTER CODE PARTY ONLY ‐‐ PEOPLE WITHIN PARTY 0001 Johnson 0002 Kennedy, John; JFK 0003 Kennedy, Robert; RFK 0004 Kennedy, Edward; "Ted" 0005 Kennedy, NA which 0006 Truman 0007 Roosevelt; "FDR" 0008 McGovern 0009 Carter 0010 Mondale 0011 McCarthy, Eugene 0012 Humphrey 0013 Muskie 0014 Dukakis, Michael 0015 Wallace 0016 Jackson, Jesse 0017 Clinton, Bill 0031 Eisenhower; Ike 0032 Nixon 0034 Rockefeller 0035 Reagan 0036 Ford 0037 Bush 0038 Connally 0039 Kissinger 0040 McCarthy, Joseph 0041 Buchanan, Pat 0051 Other national party figures (Senators, Congressman, etc.) 0052 Local party figures (city, state, etc.) 0053 Good/Young/Experienced leaders; like whole ticket 0054 Bad/Old/Inexperienced leaders; dislike whole ticket 0055 Reference to vice‐presidential candidate ? Make 0097 Other people within party reasons Card PARTY ONLY ‐‐ PARTY CHARACTERISTICS 0101 Traditional Democratic voter: always been a Democrat; just a Democrat; never been a Republican; just couldn't vote Republican 0102 Traditional Republican voter: always been a Republican; just a Republican; never been a Democrat; just couldn't vote Democratic 0111 Positive, personal, affective terms applied to party‐‐good/nice people; patriotic; etc. -

HOUSE of REPRESENTATIVES-Thursday, April 18, 1991 the House Met at 10 A.M

8568 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-HOUSE April18, 1991 HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES-Thursday, April 18, 1991 The House met at 10 a.m. H.J. Res. 222. Joint resolution to provide PRAISING THE ACTIONS OF OUR The Chaplain, Rev. James David for a settlement of the railroad labor-man TROOPS AND THE PRESIDENT'S Ford, D.D., offered the following pray agement disputes between certain railroads NEW WORLD ORDER er: represented by the National Carriers' Con ference Committee of the National Railway (Mr. BARTON of Texas asked and We see in our world, 0 God, the power Labor Conference and certain of their em was given permission to address the of might and all the forces of our in ployees; House for 1 minute and to revise and vention, and yet we do not see as clear S.J. Res. 16. Joint resolution designating extend his remarks.) ly the power of the spirit. We confess the week of April 21-27, 1991, as "National Mr. BARTON of Texas. Mr. Speaker, that we so easily recognize the might Crime Victims' Rights Week"; and I rise today to pay tribute not only to used between individuals or nations, S.J. Res. 119. Joint resolution to designate the soldiers of Operation Desert Storm, but we fail to admit the power of the April 22, 1991, as "Earth Day" to promote the but also to their Commander in Chief, spiritual forces that truly touch the preservation of the global environment. President George Bush. Their decisive lives of people. Teach us, gracious God, victory over aggression, combined with to see the energy of the spirit, encour the triumph of democracy over com aged by loyalty and integrity, by faith ALOIS BRUNNER, MOST WANTED munism, has fueled the President's fulness and allegiance, by steadfastness NAZI CRIMINAL pursuit for a new world order. -

Food & Beverage Litigation Update

Food & Beverage LITIGATION UPDATE Issue 198 • January 19, 2007 Table of Contents Legislation, Regulations and Standards [1] 2007 Farm Bill Expected to Draw New Participants . .1 [2] BSE, “Functional Foods” and Calcium on FDA Agenda .2 [3] FDA Extends “Lean” Labeling Rule to Cover Portable Products . .3 [4] FDA Focuses on California Dairy Farms in E. Coli Lettuce Investigation . .3 [5] USDA Agencies Provide Notice on BSE and Codex Fats and Oils Activities . .3 [6] Experts Urge EU to Ban Use of Mercury . .4 [7] New Jersey Law Will Prohibit Sale of Sugary Foods in Schools . .4 Other Developments [8] RAND Scientist Calls for Radical Environmental Changes to Tackle Obesity . .4 [9] Food Studies Funded by Industry Are Biased, Survey Alleges . .5 [10] CFNAP Conducts Survey of Consumer Attitudes Toward Cloned Livestock . .5 Media Coverage [11] Lawyers Predict Action on Children’s Advertising at National Conference . .6 www.shb.com Food & Beverage LITIGATION UPDATE Congress. Block also said that current USDA Legislation, Regulations Secretary Mike Johanns will likely have less influence over negotiations because the political control of and Standards Congress had changed during the interim elections. Block observed that this year’s farm bill, which will 110th Congress probably contain crop subsidies as in the past, should cost less relative to previous years because [1] 2007 Farm Bill Expected to Draw prices for basic commodities such as corn are high; New Participants he also suggested that different policy objectives, During a Webinar co-sponsored by the Food such as the promotion of increased production to Institute, former government officials, members of help feed the world’s hungry and develop alternative Congress and congressional staffers discussed what fuel sources, will come into play in the next farm bill. -

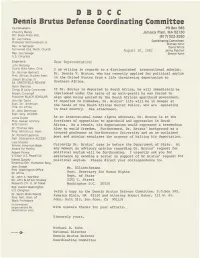

Dear Representative: John Bellamy Coord

• I Co-Convenors: PO Box 585 Chauncy Bailey Jamaica Plain, MA 02130 Dir. Black Press Inst. (617) 522-3260 Dr. Jan Carew Coordinating Committee: Professor Northwestern U. Michael Kohn Rev. AI Sampson David White Fernwood Utd. Meth. Church August 10, 1982 Jenny Patchen Rep. Gus Savage Steven Kahn U.S. Congress Endorsers: Dear Representative: John Bellamy Coord. Biko Mem. Ctte. I am writing in regards to a distinguished international scholar, Dr. Norman Bennett Dr. Dennis V. Brutus, who has recently applied for political asylum Pres. African Studies Assn. in the United States from a life threatening deportation to Joseph Bruchac III Ed. GREEN~ELD REVIEW Southern Africa. Norm Watkins Clergy & Laity Concerned If Dr. Brutus is deported to South Africa, he will immediately be Robert Chrisman imprisoned under the terms of an exit-permit he was forced to Publisher BLACK SCHOLAR sign upon being exiled by the South African apartheid government. Jennifer Davis If deported to Zimbabwe, Dr. Brutus' life will ?e in danger at Exec. Dir. American the hands of the South African Secret Police, who are operating Ctte. On Africa in that country. See attachment. Dr. John Domnisse Exec. Secy. ACCESS Lorna Evans As an international human rights advocate, Dr. Brutus is in the Pres. Hawaii Literary forefront of opposition to apartheid and oppression in South Arts Council Africa. As a result, his deportation would represent a tremendous Dr. Thomas Hale blow to world freedom. Furthermore, Dr~ Brutus' background as a Pres. African Lit. Assn. tenured professor at Northwestern UnIversity and as an acclaimed Dr. Richard Lapchick poet and scholar escalates the urgency of halting his deportation. -

America's Political System Is Broken

We can fix this. © 2015 Lynford Morton America’s political system is broken. Money has too much power in politics. Our nation faces We are the ReFormers Caucus: A bipartisan group of a governing crisis, and polls confirm an overwhelming former members of Congress and governors dedicated to majority of Americans know it. We deserve solutions now. building a better democracy – one where Americans from The 2016 election must be the last of its kind. all walks of life are represented and are empowered to tackle our nation’s most pressing challenges. That’s why we are coming together – Republicans and Democrats – to renew the promise of self-governance. We have the solutions. Let’s get to work. The ReFormers Caucus We are more than 100 strong and growing. Join us. Rep. Les Aucoin (D-OR) Rep. Tom Downey (D-NY) Rep. Barbara Kennelly (D-CT) Rep. John Edward Porter (R-IL) Sec. Bruce Babbitt (D-AZ) Rep. Karan English (D-AZ) Sen. Bob Kerrey (D-NE) Sen. Larry Pressler (R-SD) Sen. Nancy Kassebaum Baker (R-KS) Rep. Victor Fazio (D-CA) Rep. Ron Klein (D-FL) Sen. Mark Pryor (D-AR) Rep. Michael Barnes (D-MD) Rep. Harold Ford, Jr. (D-TN) Rep. Mike Kopetski (D-OR) Gov. Bill Ritter (D-CO) Rep. Charles Bass (R-NH) Amb. Wyche Fowler (D-GA) Rep. Peter Kostmayer (D-PA) Amb. Tim Roemer (D-IN) Rep. Berkley Bedell (D-IA) Rep. Martin Frost (D-TX) Amb. Madeleine Kunin (D-VT) Rep. Bill Sarpalius (D-TX) Rep. Tony Beilenson (D-CA) Rep. -

Download the Transcript

BOOK-2020/02/24 1 THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION FALK AUDITORIUM CODE RED: A BOOK EVENT WITH E.J. DIONNE JR. Washington, D.C. Monday, February 24, 2020 Conversation: E.J. DIONNE JR., W. Averell Harriman Chair and Senior Fellow, Governance Studies, The Brookings Institution ALEXANDRA PETRI Columnist The Washington Post * * * * * ANDERSON COURT REPORTING 1800 Diagonal Road, Suite 600 Alexandria, VA 22314 Phone (703) 519-7180 Fax (703) 519-7190 BOOK-2020/02/24 2 P R O C E E D I N G S MR. DIONNE: I want to welcome everybody here today. I’m E.J. Dionne. I’m a senior fellow here at Brookings. The views I am about to express are my own. I don’t want people here necessarily to hang on my views. There are so many people here. First, I want to thank Amber Hurley and Leti Davalos for organizing this event. I want to thank my agent, Gail Ross, for being here. You have probably already seen one of the 10,500,000 Mike Bloomberg ads; you know the tagline is “Mike Gets it Done.” No. Gail gets it done (laughter), so thank you for being here. One unusual person I want to -- also, another great book that you have to read, my friend, Melissa Rogers, who’s a visiting scholar here, we worked together for 20 years, her book, “Faith in American Public Life,” which has a nice double meaning, is a great book to read. And, I can't resist honoring my retired Dr. Mark Shepherd who came here today. -

Speakers of the House: Elections, 1913-2021

Speakers of the House: Elections, 1913-2021 Updated January 25, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov RL30857 Speakers of the House: Elections, 1913-2021 Summary Each new House elects a Speaker by roll call vote when it first convenes. Customarily, the conference of each major party nominates a candidate whose name is placed in nomination. A Member normally votes for the candidate of his or her own party conference but may vote for any individual, whether nominated or not. To be elected, a candidate must receive an absolute majority of all the votes cast for individuals. This number may be less than a majority (now 218) of the full membership of the House because of vacancies, absentees, or Members answering “present.” This report provides data on elections of the Speaker in each Congress since 1913, when the House first reached its present size of 435 Members. During that period (63rd through 117th Congresses), a Speaker was elected six times with the votes of less than a majority of the full membership. If a Speaker dies or resigns during a Congress, the House immediately elects a new one. Five such elections occurred since 1913. In the earlier two cases, the House elected the new Speaker by resolution; in the more recent three, the body used the same procedure as at the outset of a Congress. If no candidate receives the requisite majority, the roll call is repeated until a Speaker is elected. Since 1913, this procedure has been necessary only in 1923, when nine ballots were required before a Speaker was elected. -

Congressional Record—House H9262

H9262 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — HOUSE October 7, 2003 perfect movie Hollywood couple that America’s last half century, to have land Athletics and she passed away in her just loved each other and did not mind raised three wonderful sons and two sleep. expressing that love in front of every- outstanding daughters. Tommy, who I Millie O’Neill was an incredible woman who body. met at Boston College; Susan, who was was not often recognized for the selfless work I had the opportunity for 12 consecu- my classmate and a history major with she did for Congress and our country. Mr. tive years to travel with Tip O’Neill as me at Boston College. I have known Speaker, I want to call attention to two things he was invited around the world as them my whole life. that Mrs. O’Neill was instrumental in achiev- Speaker; but I do not know whether it This is a wonderful family, and they ing. The first was a massive fundraising effort was Tip or Millie, but one thing was balanced the demands of that journey on behalf of the Ford’s Theatre Foundation, abundantly clear, that they were not against the love and attention that a raising over $4 million dollars, for which Millie Democratic trips. They were not Re- family requires. And Millie emerged was recognized at a Gala dinner in 1984. publican trips. It was traveling with from it all with her love for Tip as The second item that I believe Mrs. O’Neill Millie and Tip O’Neill, and they made strong and as deep and as transparent deserves to be recognized for was ensuring everyone feel like just one big congres- as the two schoolkids they once were. -

19301 Winter 04 News

WINTER 2011 BBlueCrossBBlueCrosslluueeCCrroossss BBlueShieldBBlueShieldlluueeSShhiieelldd ofooofff Tennessee:TTTennessee:eennnneesssseeee:: TTiTTiiittlettlellee SponsorSSSponsorppoonnssoorr oofoofff tthetthehhee StateSSStatettaattee BasketballBBasketballBaasskkeettbbaallll ChampionshipsCChampionshipsChhaammppiioonnsshhiippss • A.F. BRIDGES AWARDS PROGRAM WINNERS • DISTINGUISHED SERVICE RECOGNITION • 2011 BASKETBALL CHAMPIONSHIP SCHEDULES TENNESSEE SECONDARY SCHOOL ATHLETIC ASSOCIATION HERMITAGE, TENNESSEE TSSAA NEWS ROUTING REPORT 2010 FALL STATE CHAMPIONS TSSAA is proud to recognize the 2010 Fall Sports Champions This routing report is provided to assist principals and athletic directors in ensuring that the TSSAA News is seen by all necessary CHEERLEADING CROSS-COUNTRY GOLF school personnel. CHEER & DANCE A-AA GIRLS Each individual should check the appropriate A-AA GIRLS Signal Mountain High School box after having read the News and pass it on Small Varsity Jazz Greeneville High School to the next individual on the list or return it to Brentwood High School AAA GIRLS the athletic administrator. AAA GIRLS Soddy-Daisy High School K Large Varsity Jazz Oak Ridge High School K Athletic Director Ravenwood High School DIVISION II-A GIRLS Girls Tennis Coach K DIVISION II-A GIRLS Franklin Road Academy Baseball Coach K Junior Varsity Pom Webb School of Knoxville Boys Tennis Coach K DIVISION II-AA GIRLS Girls Basketball Coach Arlington High School K DIVISION II-AA GIRLS Baylor School K Girls Track & Field Coach Small Varsity Pom Baylor School K Boys Basketball Coach Briarcrest Christian School A-AA BOYS K Boys Track & Field Coach A-AA BOYS Christian Academy of Knoxville K Girls Cross Country Coach Large Varsity Pom K Girls Volleyball Coach Martin Luther King High School K Boys Cross Country Coach Arlington High School AAA BOYS K Wrestling Coach AAA BOYS Hendersonville High School K Football Coach Junior Varsity Hip Hop Hardin Valley Academy K Cheerleading Coach St.