Copyright © and Moral Rights for This Thesis Are Retained by the Author And/Or Other Copyright Owners

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IRAQ COUNTRY REPORT April 2004 COUNTRY INFORMATION

IRAQ COUNTRY REPORT April 2004 COUNTRY INFORMATION & POLICY UNIT IMMIGRATION & NATIONALITY DIRECTORATE HOME OFFICE, UNITED KINGDOM CONTENTS 1 Scope of document 1.1 – 1.7 2 Geography 2.1 – 2.6 3 Economy 3.1 – 3.3 4 History Post Saddam Iraq 4.3 – 4.11 History of northern Iraq 4.12 – 4.15 5 State Structures The Constitution 5.1 – 5.2 The Transitional Administrative Law 5.3 – 5.5 Nationality and Citizenship 5.6 Political System 5.7 –5.14 Interim Governing Council 5.7 – 5.8 Cabinet 5.9 – 5.11 Northern Iraq 5.12 – 5.14 Judiciary 5.15 – 5.27 Judiciary in northern Iraq 5.28 Justice for human rights abusers 5.29 – 5.31 Legal Rights/Detention 5.32 – 5.38 Death penalty 5.34 Torture 5.35 – 5.38 Internal Security 5.39 – 5.52 Police 5.41 – 5.46 Security services 5.47 Militias 5.48 – 5.52 Prisons and prison conditions 5.53 – 5.59 Military Service 5.60 – 5.61 Medical Services 5.62 – 5.79 Mental health care 5.71 – 5.74 HIV/AIDS 5.75 – 5.76 People with disabilities 5.77 Educational System 5.78 – 5.79 6 Human Rights 6A Human Rights issues Security situation 6.4 – 6.14 Humanitarian situation 6.15 – 6.22 Freedom of Speech and the Media 6.23 – 6.28 Freedom of Religion 6.29 – 6.47 Shi’a Muslims 6.31 Sunni Muslims 6.32 Christians 6.33 – 6.38 Mandaeans 6.39 Yazidis 6.40 – 6.45 Jews 6.46 – 6.47 Freedom of Association and Assembly 6.48 Employment Rights 6.49 People Trafficking 6.50 Freedom of Movement 6.51 – 6.54 Internal travel 6.51 – 6.53 Travel to Iraq 6.54 6B Human rights - Specific Groups Ethnic Groups 6.55 – 6.74 Shi’a Arabs 6.55 – 6.60 Sunni Arabs 6.61 – -

Diyala Governorate, Kifri District

( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( (( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( Iraq- Diyala Governorate, Kifri( District ( ( ( ( (( ( ( ( ( ( ( Daquq District ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( Omar Sofi Kushak ( Kani Ubed Chachan Nawjul IQ-P23893 IQ-P05249 Kharabah داﻗوق ) ) IQ-P23842 ( ( IQ-P23892 ( Chamchamal District ( Galalkawa ( IQ-P04192 Turkey Haji Namiq Razyana Laki Qadir IQ-D074 Shekh Binzekhil IQ-P05190 IQ-P05342 ) )! ) ﺟﻣﺟﻣﺎل ) Sarhang ) Changalawa IQ-P05159 Mosul ! Hawwazi IQ-P04194 Alyan Big Kozakul IQ-P16607 IQ-P23914 IQ-P05137 Erbil IQ-P05268 Sarkal ( Imam IQ-D024 ( Qawali ( ( Syria ( IranAziz ( Daquq District Muhammad Garmk Darka Hawara Raqa IQ-P05354 IQ-P23872 IQ-P05331 Albu IQ-P23854 IQ-P05176 IQ-P052B2a6 ghdad Sarkal ( ( ( ( ( ! ( Sabah [2] Ramadi ( Piramoni Khapakwer Kaka Bra Kuna Kotr G!\amakhal Khusraw داﻗوق ) ( IQ-P23823 IQ-P05311 IQ-P05261 IQ-P05235 IQ-P05270 IQ-P05191 IQ-P05355 ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( Jordan ( ( ! ( ( ( IQ-D074 Bashtappa Bash Tappa Ibrahim Big Qala Charmala Hawara Qula NaGjafoma Zard Little IQ-P23835 IQ-P23869 IQ-P05319 IQ-P05225 IQ-P05199 ( IQ-P23837 ( Bashtappa Warani ( ( Alyan ( Ahmadawa ( ( Shahiwan Big Basrah! ( Gomatzbor Arab Agha Upper Little Tappa Spi Zhalan Roghzayi Sarnawa IQ-P23912 IQ-P23856 IQ-P23836 IQ-P23826 IQ-P23934 IQ-P05138 IQ-P05384 IQ-P05427 IQ-P05134 IQ-P05358 ( Hay Al Qala [1] ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( Ibrahim Little ( ( ( ( ( ( ( Ta'akhi IQ-P23900 Tepe Charmuk Latif Agha Saudi ArabiaKhalwa Kuwait IQ-P23870 Zhalan ( IQ-P23865 IQ-P23925 ( ( IQ-P23885 Sulaymaniyah Governorate Roghzayi IQ-P05257 ( ( ( ( ( Wa(rani -

Iraq- Salah Al-Din Governorate, Daur District

( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( Iraq- Salah al-Din Governorate, Daur District ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( Raml ( Shibya Al-qahara ( Sector 41 - Al Khazamiya Mukhaiyam Tmar Zagilbana ( IQ-P16758 abdul aziz IQ-P16568 Summaga Al Sharqiya - illegal Kirkuk District IQ-P16716 Muslih IQ-P16862 IQ-P16878 Turkey Albu IQ-P23799 Ramel [1] IQ-P16810 ( Upper Sabah [2] Shahatha Abdul Aziz Zajji IQ-P16829 IQ-P23823 IQ-P16757 IQ-P16720 IQ-P16525 ( Khashamina ﻛرﻛوك ( ( Albu IQ-P16881 Mosul! ! ( ( IQ-P23876 ( Shahiwan Sabah [1] Albu shahab Erbil ( Gheda IQ-P23912 IQ-D076 TALAA IQ-P16553 IQ-P16554 ( IQ-P16633 ( Tamur Syria Iran AL-Awashra AL-DIHEN ( ( ( Tamour IQ-P16848 Hulaiwa Big IQ-P16545 IQ-P16839 Baghdad ( ( IQ-P16847 IQ-P23867 ( ( Khan Mamlaha ( ( Ramadi! !\ IQ-P23770 Dabaj Al Jadida ( Salih Hulaiwa ( ( ( ( IQ-P23849 village Al Mubada AL- Ugla (JLoitrtlde an Najaf! (( IQ-P23671 village IQ-P16785 IQ-P23868 ( ( Ta`an ( Daquq District ( IQ-P23677 Al-Mubadad Basrah! IQ-P23804 ( Maidan Yangija ( IQ-P16566 Talaa dihn ( IQ-P16699 Albu fshka IQ-P23936 داﻗوق ) Al Washash al -thaniya ( Khashamila KYuawnija( iBtig village IQ-P16842 IQ-P16548 Albu zargah Saudi Arabia Tal Adha ( IQ-P23875 IQ-P23937 IQ-P23691 IQ-D074 ( IQ-P16557 ( ( ( Talaa dihn ( IQ-P16833 ( al-aula Alam Bada IQ-P16843 ( IQ-P23400 Mahariza ( IQ-P16696 ( Zargah ( IQ-P16886 Ajfar Kirkuk Governorate ( Qaryat Beer Chardaghli Sector 30 IQ-P23393 Ahmed Mohammed Shallal IQ-P23905 IQ-P23847 ﻛرﻛوك ) Al Rubidha ( ( ( Abdulaziz Bi'r Ahmad ( IQ-P23798 ( IQ-G13 -

Download the COI Focus

OFFICE OF THE COMMISSIONER GENERAL FOR REFUGEES AND STATELESS PERSONS PERSONS COI Focus IRAQ Security Situation in Central and Southern Iraq 20 March 2020 (update) Cedoca Original language: Dutch DISCLAIMER: This COI-product has been written by Cedoca, the Documentation and Research Department of the CGRS, and it provides information for the processing of applications for international protection. The document does not contain policy guidelines or opinions and does not pass judgment on the merits of the application for international protection. It follows the Common EU Guidelines for processing country of origin information (April 2008) and is written in accordance with the statutory legal provisions. The author has based the text on a wide range of public information selected with care and with a permanent concern for crosschecking sources. Even though the document tries to cover all the relevant aspects of the subject, the text is not necessarily exhaustive. If certain events, people or organizations are not mentioned, this does not mean that they did not exist. All the sources used are briefly mentioned in a footnote and described in detail in a bibliography at the end of the document. Sources which have been consulted but which were not used are listed as consulted sources. In exceptional cases, sources are not mentioned by name. When specific information from this document is used, the user is asked to quote the source mentioned in the bibliography. This document can only be published or distributed with the written consent of the Office of the Commissioner General for Refugees and Stateless Persons. TO A MORE INTEGRATED MIGRATION POLICY, THANKS TO AMIF Rue Ernest Blerot 39, 1070 BRUSSELS T 02 205 51 11 F 02 205 50 01 [email protected] www.cgrs.be IRAQ. -

Iraq- Wassit Governorate, Badra District

( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( Iraq- W(assi( t Governorate, Badra District ( ( ( ( ( ( ( Karim ( ( Sh`alan IQ-P12003 IQ-P12115 Turkey Mukhaybir ( Mosul! ! ( ( ( IQ-P12050 Erbil Baba Mahmud Gurzuddin Ayayi Syria Iran Hasan IQ-P11912 IQ-P12032 ( IQ-P11948 ( ( ( ( Baghdad Abruk ! Awad as Hay Karaz Muhsin Ramadi IQ-P11870 IQ-P12049 !\ ( ( Suwaylim ( Al Din IQ-P11977 IQ-P11908 Salman Jordan Najaf! Hizam Muhammad [2] Farraj IQ-P12044 IQ-P12112 IQ-P11980 ( Basrah! ( ( ( ( ( ( Abd al Saudi Arabia Kuwait Kisarah Hassun IQ-P11866 IQ-P11953 Mahar `Ali Abd Allah ( ( ( ( ( ( Ariz IQ-P12027 Salim IQ-P11906 IQ-P11868 ( ( Binyan ( IQ-P11919 Mutlag al Humayyid Ma'mur Lihmah Shanun Muhayhay IQ-P12054 IQ-P12024 IQ-P11981 IQ-P12048 ( ( ( ( Tursak IQ-P12136 ( ( Diyala Governorate Dal`ah Rashid Abbas` دﯾﺎﻟﻰ ) IQ-P11924 ( IQ-G10 Midan [1] Iran Bustan `Abd IQ-P12038 ( al Hasan IQ-P11922 ( Baladrooz District ( ﺑﻠدروز ( IQ-D057 Insif IQ-P11993 ( ( ( Amil IQ-P11903 ( ( ( Sultan [1] IQ-P12127 ( Hashimah Kani Sakht IQ-P21257 IQ-P21271 ( ( Abd al `Ali IQ-P21218 ( Salih muhsen wa jama'atih Al-seha wa IQ-P21289 (umm al-riwaq IQ-P21242 (( Umm ar Rawwaf Ulwi IQ-P21299 IQ-P21297 ( Al-nishan Mahalat Al-ghazaly Zaly ab /1 Hurkayjah ( Mashali Beg al-aswad al-jami'e IQ-P21227 IQ-P21300 IQ-P21264 IQ-P21281 ( Faris IQ-P21239 IQ-P2127(6 ( ( ( ( ( al-sa'adon ( ( ( ( IQ-P21254 Dahnok Al-ta'an ( Zurbatiya ( ( Rustim ( ( IQ-P21251 ( (al-ta'an / 4 ) Deh Nuk IQ-P21302 IQ-P21287( IQ-P21244 ( IQ-P21253 Qiyawi ( Bahramabad IQ-P21285 Al-me'dan ( Arafat IQ-P21248 ( IQ-P21236 Badrah -

Investment Map of Iraq 2016

Republic of Iraq Presidency of Council of Ministers National Investment Commission Investment Map of Iraq 2016 Dear investor: Investment opportunities found in Iraq today vary in terms of type, size, scope, sector, and purpose. the door is wide open for all investors who wish to hold investment projects in Iraq,; projects that would meet the growing needs of the Iraqi population in different sectors. Iraq is a country that brims with potential, it is characterized by its strategic location, at the center of world trade routes giving it a significant feature along with being a rich country where I herby invite you to look at Iraq you can find great potentials and as one of the most important untapped natural resources which would places where untapped investment certainly contribute in creating the decent opportunities are available in living standards for people. Such features various fields and where each and characteristics creates favorable opportunities that will attract investors, sector has a crucial need for suppliers, transporters, developers, investment. Think about the great producers, manufactures, and financiers, potentials and the markets of the who will find a lot of means which are neighboring countries. Moreover, conducive to holding new projects, think about our real desire to developing markets and boosting receive and welcome you in Iraq , business relationships of mutual benefit. In this map, we provide a detailed we are more than ready to overview about Iraq, and an outline about cooperate with you In order to each governorate including certain overcome any obstacle we may information on each sector. In addition, face. -

Weekly Iraq .Xplored Report 02 November 2019

Weekly Iraq .Xplored report 02 November 2019 Prepared by Risk Analysis Team, Iraq garda.com Confidential and proprietary © GardaWorld Weekly Iraq .Xplored Report 02 November 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS .......................................................................................................................................... 2 ACTIVITY MAP .................................................................................................................................................... 3 OUTLOOK ............................................................................................................................................................. 4 Short term outlook ............................................................................................................................................. 4 Medium to long term outlook ............................................................................................................................ 4 SIGNIFICANT EVENTS ...................................................................................................................................... 5 Violent protests in Baghdad and southern Iraq continue .............................................................................. 5 IS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi killed in US SF operation in Syria .............................................................. 5 THREAT MATRIX ............................................................................................................................................... -

Weekly Report 23 29July.Pdf (English)

IMMAP - MOSUL HUMANITARIAN RESPONSE 23 JULY - 29 JULY WEEKLY EXPLOSIVE INCIDENTS REPORT 2017 18 33 13 64 Airstrikes + Explosive Hazards + Armed Clash Areas = Explosive Incidents JULY 23, 2017 JULY 24, 2017 Popular Mobilization Forces repelled an ISIS attack in Fatha area in Iraqi Military Forces Iraqi Military Forces found a mass Baiji distirct and Synia-Haditha sector in grave which contained 60 corpses 44 of • Launched strike on an ISIS car and killed Salah Al-Din. them belongs to the Police Forces of all of them in Mutaibija area in Salah Mosul in Maidan area in Mosul Al-Din. Al-Qadimah. ISIS launched an attack on the Security • Found and cleared IEDs and weapons in Forces in Ma’ash Market in western side Mosul Al-Qadimah. of Mosul city and killed four members. • Killed ISIS members while trying to Popular Mobilization Forces escape from Telafar district to the Syrian • Found and cleared dozens of IEDs and border. booby-trapped houses on the road JULY 26, 2017 between Baiji-Mosul districts. • Shelled ISIS positions on the Iraq-Syria Government Security Force Popular Mobilization Forces found Launched airstrikes on Shumayt Bridge border. three mass graves belonging to yazidi in Hawiga district in Kirkuk. sectarian in Seba Shaikhder village of • Killed ISIS members and destroyed the Sinjar district in Ninewa. vehicles belonging to them on the Iraq-Syria border. Popular Mobilization Forces • Repelled an ISIS attack on Tikrit district caused an explosion in a house ISIS in Salah Al-Din by destroying several which injured a man in Ba’shiqa JULY 25, 2017 ISIS SVBIEDs which were coming from sub-district in Mosul. -

The Future of Iraq: Dictatorship, Democracy

THE FUTURE OF IRAQ DICTATORSHIP, DEMOCRACY, OR DIVISION? Liam Anderson and Gareth Stansfield 01 anderson fm 12/15/03 11:57 AM Page i THE FUTURE OF IRAQ This page intentionally left blank 01 anderson fm 12/15/03 11:57 AM Page iii THE FUTURE OF IRAQ DICTATORSHIP, DEMOCRACY, OR DIVISION? Liam Anderson and Gareth Stansfield 01 anderson fm 12/15/03 11:57 AM Page iv THE FUTURE OF IRAQ Copyright © Liam Anderson and Gareth Stansfield, 2004. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. First published 2004 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN™ 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010 and Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire, England RG21 6XS. Companies and representatives throughout the world. PALGRAVE MACMILLAN is the global academic imprint of the Palgrave Macmillan division of St. Martin’s Press, LLC and of Palgrave Macmillan Ltd. Macmillan® is a registered trademark in the United States, United Kingdom and other countries. Palgrave is a registered trademark in the European Union and other countries. ISBN 1–4039–6354–1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Anderson, Liam D. The future of Iraq : dictatorship, democracy, or division? / by Liam Anderson and Gareth Stansfield. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1–4039–6354–1 hardcover 1. Iraq—Politics and government—1958- 2. Iraq War, 2003. 3. Democracy—Iraq. 4. Iraq—Ethnic relations. I. Stansfield, Gareth R. V. II. Title. DS79.65.A687 2004 956.7044’3—dc22 2003058846 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. -

Weekly Report Jun 3 to JUNE2 9

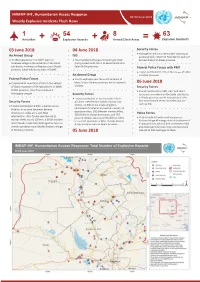

iMMAP-IHF, Humanitarian Access Response 03-09 June 2018 Weekly Explosive Incidents Flash News 1 54 8 63 Airstrikes + Explosive Hazards + Armed Clash Areas = Explosive Incidents 03 June 2018 04 June 2018 Security Forces ● Managed to kill a suicide bomber wearing an An Armed Group ISIS explosive belt in the First Tash district south of ● An IED exploded on the SWAT patrol in ● Four members of Saraya Al-Salam got killed Ramadi district in Anbar province. Mukhesa village in the outskirts of Abu Saida during a clash with ISIS in Al-Samarra Island in sub-district northeast of Baquba city in Diyala Salah Al-Din province. Federal Police Forces with PMF province, which killed a member of SWAT. ● Found and cleared 3 IEDs in the village of Safira An Armed Group in Kirkuk province. Federal Police Forces ● An IED exploded near the north terminal of ● Clashed with members of ISIS in the valleys Mosul city in Ninewa province, which injured 5 06 June 2018 of Qara mountain of Shirqat district in Salah civilians. Security Forces Al-Din province, also they released 2 ● Found and cleared an IED, ruler and small kidnapped people. Security Forces battery in an orchard of Abu Saida sub-district ● Found and cleared 51 locally made IEDs in in Diyala province, worth noting that it’s the Security Forces Al-Salam intersec�on towards Falahat train first time that the terrorists create and use such an IED. ● Found and cleared 2 IEDs, a tunnel and a sta�on, 12 IEDs in the shape of gallons hideout in an area between Bararat contained C4 material, an Austrian rocket, 22 explosive rulers, 300 different mortars fillers, checkpoint, Salby area and Hadr 250 different mortar detonators, and TNT Police Forces intersection. -

Investment Map of Iraq 2019 Republic of Iraq Presidency of Council of Ministers National Investment Commission

Republic of Iraq Presidency of Council of Ministers National Investment Commission Investment Map of Iraq 2019 Republic of Iraq Presidency of Council of Ministers National Investment Commission Investment Map of Iraq 2019 www.investpromo.gov.iq [email protected] Dear investor: Investment opportunities found in Iraq today vary in terms of type, size, scope, sector, and purpose. the door is wide open for all investors who wish to hold investment projects in Iraq,; projects that would meet the growing needs of the Iraqi population in different sectors. In this map, we provide a detailed overview about Iraq, and an outline about each governorate including certain information on each sector. In addition, you will find a list of investment I herby invite you to look at Iraq as opportunities that was classified as per one of the most important places the available investment opportunities in where untapped investment each economic sector in each opportunities are available in various governorate. This updated map includes a fields and where each sector has a number of investment opportunities that crucial need for investment. were presented by the concerned Ministries. Think about the great potentials and We reiterate our efforts to increase the markets of the neighboring economic and investment cooperation countries. Moreover, think about our with all countries of the world through real desire to receive and welcome continuous efforts to stimulate and attract you in Iraq , we are more than ready investments, reconstruction and to cooperate with you In order to development in productive fields with overcome any obstacle we may face. -

Pdf | 238.97 Kb

IOM EMERGENCY NEEDS ASSESSMENTS POST FEBRUARY 2006 DISPLACEMENT IN IRAQ 1 NOVEMBER 2008 MONTHLY REPORT Following the February 2006 bombing of the Samarra Al-Askari Mosque, escalating sectarian violence in Iraq caused massive displacement, both internal and to locations abroad. In coordination with the Iraqi government’s Ministry of Displacement and Migration (MoDM), IOM continues to assess Iraqi displacement through a network of partners and monitors on the ground. Most displacement over the past five years (since 2003) occurred in 2006 and has since slowed. However, displacement continues to occur in some locations and the humanitarian situation of those already displaced is worsening. Some Iraqis are returning, but their conditions in places of return are extremely difficult. The estimated number of displaced since February 2006 is almost 1,596,448 individuals1. In addition, there are an estimated 1,212,108 individuals2 who were internally displaced before February 2006. SUMMARY OF CURRENT IRAQI DISPLACEMENT AND RETURN: Returns Government and security forces in Iraq continue to emphasize improved security and opportunity for returns, attempting to facilitate the process where possible. In Baghdad, returnees are requested to make themselves known to the security forces, so as to ensure that areas of return are routinely patrolled and kept secure. Overall, returns are continuing at a slow but significant rate, while displacement is still slowed nationwide, limited to isolated events such as the recent displacement of Christian families in Mosul. Returnee families are in need of humanitarian assistance in order to reconstruct their homes and their livelihoods. IDP and host community children crowd In Hurriya neighborhood of Baghdad, the one together in a primary school in Wassit.