Digital Art in the “Third World” Context of the Philippines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

INTERLACED JOURNEYS INTERLACED JOURNEYS Diaspora and the Contemporary in Southeast Asian Art

INTERLACED JOURNEYS INTERLACED INTERLACED JOURNEYS Diaspora and the Contemporary in Southeast Asian Art Edited by Patrick D. Flores & Loredana Pazzini-Paracciani Diaspora and the Contemporary in Southeast Asian Art INTERLACED JOURNEYS| Diaspora and the Contemporary in Southeast Asian Art brings together the work of some of the most engaging art historians and curators from Southeast Asia and beyond that explores the notion of diaspora in contemporary visual culture. Regional attention on this particular condition of movement and resettlement has oen been conned to sociological studies, while the place of diaspora in Southeast Asian contemporary art remains mostly unexplored. is is the rst anthology to examine the subject from the complex perspective of artistic and curatorial practice as it attempts to propose multiple narratives of diaspora in relation to a range of articulations in the contemporary context. INTERLACED JOURNEYS Diaspora and the Contemporary in Southeast Asian Art Edited by Patrick D. Flores & Loredana Pazzini-Paracciani ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Editing Patrick D. Flores Loredana Pazzini-Paracciani Copyediting Thelma Arambulo Carlos Quijon, Jr. First and foremost, we would like to express our sincere appreciation to the writers whose insightful Design chapters, developed for this publication, have helped to advance the discourse on migration and Belle Leung for Osage Design diaspora, Southeast Asia, and contemporary Southeast Asian art. We hope this publication to be but the initial step towards a larger research and exploration on the topic of migration and border crossing Publication Coordination in the region. Carlos Quijon, Jr. Our heartfelt gratitude goes to the artists included in this book whose invaluable art practices and Publication Support viewpoints have inspired the writers and editors. -

David Medalla

DAVID MEDALLA Nació en Manila en 1942. David Medalla es considerado uno de los pioneros del land art, del kinetic art, del arte conceptual, del arte participativo y del live art. A la edad de 12 años asistió a la Universidad de Columbia en Nueva York, como estudiante especial. Estudió teatro griego antiguo con Moses Hadas, teatro moderno con Eric Bentley, literatura moderna con Lionel Trilling, filosofía moderna con John Randall. También asistió al taller de poesía de Leonie Adams. En Nueva York, motivado por el poeta Jose García Villa y por el actor James Dean, David Medalla decide tomarse en serio la pintura. Medalla regresa a Manila a fines de los cincuenta, en donde se encuentra con los primeros patrocinadores de su obra, que incluyen al poeta catalán Jaime Gil de Biedma, al artista español Fernando Zóbel de Ayala y al pianista norteamericano Albert Faurot. En los años sesenta en París, el filósofo francés Gaston Bachelard introdujo la performance de Medalla, titulada "The Poet in Abyssinia: an imaginary biography of Arthur Rimbaud" en la Academia de Raymond Duncan, hermano de la legendaria bailarina Isadora Duncan, a quien le dedicó una performance con Shoe Taylor Guinness en el British Museum in 2001. En 1980, el poeta Louis Aragon (co-fundador del movimiento surrealista con André Breton y Philippe Soupault) introdujo otra de las performances de David Medalla, titulada "Anges du Jour, Anges du Nuit". Franklin Furnace y la Jerome Foundation patrocinaron la performance de Medalla "Five Immortals at Drop Dead Prices" en el Great Hall of Cooper Union en 1994 en Nueva York. -

Glimpses of Before 1970S Performance Art in the UK

Glimpses of Before 1970s Performance Art in the UK Compiled & written by Helena Goldwater 2016 LADA Study Room Guides As part of the continuous development of the Study Room we regularly commission artists and thinkers to write personal Study Room Guides on specific themes. The idea is to help navigate Study Room users through the resource, enable them to experience the materials in a new way and highlight materials that they may not have otherwise come across. All Study Room Guides are available to view in our Study Room, or can be viewed and/or downloaded directly from their Study Room catalogue entry. Please note that materials in the Study Room are continually being acquired and updated. For details of related titles acquired since the publication of this Guide search the online Study Room catalogue with relevant keywords and use the advance search function to further search by category and date. Bernsteins ‘Taking Measurements of yourselves as Artists`” Fairlight Glen, Hastings 1972 Glimpses of Before: 1970s UK Performance Art by Helena Goldwater Commissioned by Live Art Development Agency, and Queen Mary, University of London’s Research Project ‘Performance and Politics in the 1970s’ Published by Live Art Development Agency (2016) www.1970s.thisisliveart.co.uk www.1970s.thisisliveart.co.uk Contents Foreword ............................................................................................................... 4 Prelude ................................................................................................................. -

Conceptualism – Intersectional Readings, Inter National Framings

Conceptualism – Intersectional Readings, Inter national Framings Situating ‘Black Artists & Modernism’ in Europe CONTENTS • Nick Aikens, susan pui san lok, Sophie Orlando Introduction 4 KEYNOTE • Valerie Cassel Oliver Through the Conceptual Lens: The Rise, Fall and Resurrection of Blackness 218 KEYNOTE • Iris Dressler Subversive Practices: Art Under Conditions of Political Repression in 1960s and 1980s South America and Europe 14 IV DAVID MEDALLA 244 I CONCEPTUALISM AND INTERSECTIONAL READINGS 30 • Nick Aikens Introduction 246 • Nick Aikens, Annie Fletcher Introduction 32 • David Dibosa Ambivalent Thresholds: David Medalla’s Conceptualism and ‘Queer British Art’ 250 • Alexandra Kokoli Read My QR: Quilla Constance and the Conceptualist Promise of Intelligibility 36 • Eva Bentcheva Conceptualism-Scepticism and Creative Cross-pollinations in the Work of David Medalla, 1969–72 262 • Elisabeth Lebovici The Death of the Author in the Age of the Death of the Authors 54 • Sonia Boyce Dearly Beloved: Transitory Relations and the Queering of ‘Women’s Work’ in David Medalla’s A Stitch in Time (1967–72) 282 • susan pui san lok Found and Lost: A Genealogy of Waste? 68 • Wei Yu David Medalla and Li Yuan-chia: Conceptual Projects from the 1960s to 1970s 300 II NIL YALTER 96 • Sarah Wilson Introduction 98 V CONCEPTUALISM AND INTERNATIONAL FRAMINGS 312 • Fabienne Dumont Is Nil Yalter’s Work Compatible with Black • susan pui san lok Introduction 314 Conceptualism? An Analysis Based on the FRAC Lorraine Collection 104 • Alice Correia Allan deSouza and Mohini -

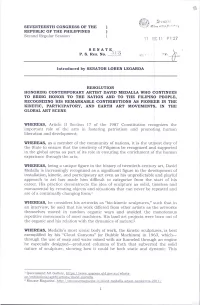

Aiyi S C Tin Ti' SEVENTEENTH CONGRESS of the ) 'I'- 77/^ 6 ( Ifirt of M REPUBLIC of the PHILIPPINES ) Second Regular Session ) *17 DEC 11 P 3 ■•27

Aiyi S c tin ti' SEVENTEENTH CONGRESS OF THE ) 'i'- 77/^ 6( ifirt of m REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES ) Second Regular Session ) *17 DEC 11 P 3 ■•27 S E N A T E,_ P. S. Res. No. Hl ( ! ' ' ’’V: Introduced by SENATOR LOREN LEGARDA RESOLUTION HONORING CONTEMPORARY ARTIST DAVID MEDALLA WHO CONTINUES TO BRING HONOR TO THE NATION AND TO THE FILIPINO PEOPLE, RECOGNIZING HIS REMARKABLE CONTRIBUTIONS AS PIONEER IN THE KINETIC, PARTICIPATORY, AND EARTH ART MOVEMENTS, IN THE GLOBAL ART SCENE WHEREAS, Article II Section 17 of the 1987 Constitution recognizes the important role of the arts in fostering patriotism and promoting human liberation and development; WHEREAS, as a member of the community of nations, it is tlie utmost duty of the State to ensure that the creativity of Filipinos be recognized and supported in the global arena as part of its role in ensuring the enrichment of the human experience through the arts; WHEREAS, being a unique figure in the history of twentieth-century art, David Medalla is increasingly recognized as a significant figure in the development of installation, kinetic, and participatory art even as his unpredictable and playful approach to art has made him difficult to categorize from the start of his career. His practice deconstructs the idea of sculpture as solid, timeless and monumental by creating objects and situations that can never be repeated and are of a continually changing form;1 WHEREAS, he considers his artworks as “bio-kinetic sculptures,” such that in an interview, he said that his work differed from other artists as the artworks themselves moved in random organic ways and avoided the monotonous repetitive movements of most machines. -

“Total Community Response”: Performing the Avant-Garde As a Democratic Gesture in Manila

“Total Community Response”: Performing the Avant-garde as a Democratic Gesture in Manila Patrick D. Flores Southeast of Now: Directions in Contemporary and Modern Art in Asia, Volume 1, Number 1, March 2017, pp. 13-38 (Article) Published by NUS Press Pte Ltd DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/sen.2017.0001 For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/646476 [ Access provided at 3 Oct 2021 20:14 GMT with no institutional affiliation ] “Total Community Response”: Performing the Avant-garde as a Democratic Gesture in Manila PATRICK D. FLORES “This nation can be great again.” This was how Ferdinand Marcos enchanted the electorate in 1965 when he won his first presidential election at a time when the Philippines “prided itself on being the most ‘advanced’ in the region”.1 In his inaugural speech titled “Mandate to Greatness”, he spoke of a “national greatness” founded on the patriotism of forebears who had built the edifice of the “first modern republic in Asia and Africa”.2 Marcos conjured prospects of encompassing change: “This vision rejects and discards the inertia of centuries. It is a vision of the jungles opening up to the farmers’ tractor and plow, and the wilderness claimed for agriculture and the support of human life; the mountains yielding their boundless treasure, rows of factories turning the harvests of our fields into a thousand products.” 3 This line on greatness may prove salient in the discussion of the avant- garde in Philippine culture in the way it references “greatness” as a marker of the “progressive” as well as of the “massive”. -

Signals Crossing Borders: Cybernetic Words and Images and 1960S Avant-Garde Art

Interfaces Image Texte Language 38 | 2017 Crossing Borders: Appropriations and Collaborations Signals Crossing Borders: Cybernetic Words and Images and 1960s Avant-Garde Art John A. Tyson Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/interfaces/312 DOI: 10.4000/interfaces.312 ISSN: 2647-6754 Publisher: Université de Bourgogne, Université de Paris, College of the Holy Cross Printed version Date of publication: 1 January 2017 Number of pages: 65-103 ISSN: 1164-6225 Electronic reference John A. Tyson, « Signals Crossing Borders: Cybernetic Words and Images and 1960s Avant-Garde Art », Interfaces [Online], 38 | 2017, Online since 13 June 2018, connection on 04 January 2021. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/interfaces/312 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/interfaces.312 Les contenus de la revue Interfaces sont mis à disposition selon les termes de la Licence Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International. 65 SIGNALS CROSSING BORDERS: CYBERNETIC WORDS AND IMAGES AND 1960S AVANT-GARDE ART John A. Tyson We hope to provide a forum for all those who believe passionately in the correlation of the arts and Art’s Imaginative integration with technology, science, architecture and our entire environment. We believe that such an integration can only be accomplished by most rigorous means: by the exercise of the highest academic standards, and when society gives to the artist its available materials, its support, and complete freedom in the pursuit of his (the artist’s) art. —David Medalla and Paul Keeler This frank, hopeful introduction appears on the front page of the first issue of the avant-garde publication Signalz: Newsbulletin of the Centre for Advanced Creative Study (the sole one that employs a deviant “z” spelling) (Fig. -

David Medalla CV

David Medalla CV David Medalla is a pioneer of land art, kinetic art, participatory art and live art. He was born in 1942 in Manila, Philippines. At the age of 12 Medalla was admitted as a special student at Colombia University in New York upon the recommendation of american poet Mark van Doren. Medalla's tutor at Colombia was Professor Moses Hadas under whom he studied ancient greek drama. Medalla also attended the lectures on modern drama by Eric Bentley, modern literature by Lionel Trilling, modern philosophy by John Randall and the poetry workshop by Leonie Adams. In New York City David met the american actor James Dean and the filipino poet José Garcia Villa who encouraged Medalla's early interest in painting. When he returned to Manila in the late fifties, he met Jaime Gil de Biedma (the catalan poet) and the painter Fernando Zobel de Ayala, who became the earliest patrons of Medalla's art. In Paris in 1960, the French philosopher Gaston Bachelard introduced David's first performance in France at the Academy of Raymond Duncan, the brother of the great american dancer Isadora Duncan. Years later in Paris, the French poet Louis Aragon (co- founder of surrealism with André Breton) introduced another performance by Medalla and hailed the filipino artist as a genius. Marcel Duchamp made a medallic object for David. From 1964 -1966 Medalla edited SIGNALS newsbulletin in London. In 1967 he initiated the Exploding Galaxy, an international confluence of multi-media artists. From 1974 - 1977 he was chairman of Artists for Democracy and director of the Fitzrovia Cultural Centre in London. -

David Medalla | I Am an Enigma, Even to My Self July 14 – August 5, 2016

David Medalla | I am an enigma, even to my self July 14 – August 5, 2016 VENUS 980 Madison Avenue New York, NY 10075 (New York, NY)—This July, VENUS is pleased to present its second exhibition of work by David Medalla, a pioneer of kinetic and participatory art. In 2014 VENUS showcased Cloud Canyons, an eight-foot-tall bubble machine considered to be Medalla’s most iconic work (currently on view at the TATE Modern). The second exhibition, titled I am an enigma, even to my self, will feature paintings, photographs, sculpture, ephemera, and an interactive installation, providing an overview of Medalla’s artistic practice. For the exhibition, Medalla recounts: In the late ‘60s, I met two ex-lovers at London’s Heathrow airport and gave them each a handkerchief, along with a packet of needles and several spools of cotton thread. I instructed them to stitch anything they wanted on the handkerchiefs— poems, names, messages, drawings, etc. Years later, I met a backpacker at Schiphol airport in Amsterdam carrying a totem-like pole of pieces of multicolored cloths stitched together with various objects including old Chinese coins, keys, David Medalla Dreaming of the Mystic Rose, empty cigarette packets, dried leaves, barks and roots of tropical trees attached. New York City, 1954. The backpacker revealed that someone had given it to him in Bali. Upon taking a closer look, I was amazed to find that the bottom piece of cloth was one of the original handkerchiefs I had given away. This event marked the beginning of A Stitch in Time, a pioneering work of participatory art in which needles and spools of colored thread are made available to visitors to stitch messages onto a suspended length of fabric. -

LEFT SHIFT: RADICAL ART in 1970S BRITAIN

1st Revise 22/10/01 138 X 216mm LEFT SHIFT 1st Revise 22/10/01 138 X 216mm This book is dedicated to the memory of Jo Spence (1934–92), the bravest woman I knew during the 1970s 1st Revise 22/10/01 138 X 216mm LEFT SHIFT RADICAL ART IN 1970s BRITAIN JOHN A. WALKER I.B.Tauris Publishers LONDON . NEW YORK 1st Revise 22/10/01 138 X 216mm Published in 2002 by I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd 6 Salem Road, LondonW2 4BU 175 Fifth Avenue, NewYorkNY 10010 www.ibtauris.com In the United States of America and in Canada distributed by St Martin’s Press, 175 Fifth Avenue, NewYorkNY 10010 Copyright # John A.Walker, 2002 The right of John A.Walker to be identi¢ed as the author of this work has been asserted by the author in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or any part thereof, may not be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. ISBN1 86064 hardback ISBN1 86064 paperback A full CIP record for this book is available from the British Library A full CIP record for this book is available from the Library of Congress Library of Congress catalog card: available Project Management by SteveTribe, London Printed and bound in Great Britain by MPG Books Ltd 1st Revise 22/10/01 138 X 216mm Contents List of illustrations vii Acknowledgements ix Introduction 1 Chapter 1: 1970 21 Chapter 2: 1971 44 Chapter 3: 1972 65 Chapter 4: 1973 91 Chapter 5: 1974 111 Chapter 6: 1975 137 Chapter 7: 1976 157 Chapter 8: 1977 182 Chapter 9:1978 208 Chapter 10: 1979 230 Conclusion: Aftermath 253 Notes 259 Bibliography 275 Index 279 v 1st Revise 22/10/01 138 X 216mm 1st Revise 22/10/01 138 X 216mm Illustrations 1. -

Kineticart0000bret Kinetic Art Guy Brett

Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2020 with funding from Kahle/Austin Foundation https://archive.org/details/kineticart0000bret Kinetic Art Guy Brett Studio-Vista: London Reinhold Book Corporation: New York Acknowledgments The photos in this book, the selection of works, the text, are inevitably brought together in the context of an in¬ tellectual argument. But this argument doesn't bind the works or attach itself to them. Another writer might make a different selection of artists under the same title. And this could be good, because it could prevent the formation of a clearly-defined style and therefore bring us closer to the perception of individual artists. I am very grateful to the artists who gave me photo¬ graphs of their work, to Clay Perry for helping me with photographs, and to the following for giving permission to reproduce works in their collection : The Tate Gallery, London 22; Pierre Matisse, New York 14; Max Bill 14, 17; Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam 15; Kroller-Muller Museum, Otterloo 16; Moderna Museet, Stockholm 16, 23; Mme Roberta Gonzalez 18; Miriam Gabo 19; Mus6e Nationale d'Art Moderne, Paris 19; Rose Fried Gallery, New York 20; Museum Haus Lange, Krefeld 26; Shunk-Kender, photographer 25; Alfred Barr 21 ; Busch Reisinger Museum of Harvard University 24; Indica Gallery, London 57, 87; M. Visser 71 ; Lucio Fontana 71; Marlborough Gerson Gallery 84, 85; Galerie Alexandre lolas, Paris 34, 37, 38, 39; Kunsthalle, Baden- Baden 36. I especially want to acknowledge here the work done by Paul Keeler and David Medalla at Signals, London, (1964-66) in exhibiting the work of several of the artists in this book and arousing enthusiasm for it. -

Helen Chadwick

LADA Study Room Guides As part of the continuous development of the Study Room we regularly commission artists and thinkers to write personal Study Room Guides on specifc themes. The idea is to help navigate Study Room users through the resource, enable them to experience the materials in a new way and highlight materials that they may not have otherwise come across. All Study Room Guides are available to view in our Study Room, or can be viewed and/or downloaded directly from their Study Room catalogue entry. Please note that materials in the Study Room are continually being acquired and updated. For details of related titles acquired since the publication of this Guide search the online Study Room catalogue with relevant keywords and use the advance search function to further search by category and date. Bernsteins ‘Taking Measurements of yourselves as Artists`” Fairlight Glen, Hastings 1972 Glimpses of Before: 1970s UK Performance Art by Helena Goldwater Commissioned by Live Art Development Agency, and Queen Mary, University of London’s Research Project ‘Performance and Politics in the 1970s’ Published by Live Art Development Agency (2016) www.1970s.thisisliveart.co.uk www.1970s.thisisliveart.co.uk Contents Foreword ............................................................................................................... 4 Prelude .................................................................................................................. 7 Artists ................................................................................................................