Brine Density & Persistence: Part 1 Physical Properties of a Brine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

3D Convection, Phase Change, and Solute Transport in Mushy Sea Ice

3D convection, phase change, and solute transport in mushy sea ice Dan Martin, James Parkinson, Andrew Wells, Richard Katz Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (USA), Oxford University (UK). Summary: ● Simulated brine drainage via 3-D convection in porous mushy sea ice ● Shallow region near ice-ocean interface is desalinated by many small brine channels ● Full-depth “mega-channels” allow drainage from saline layer near top of ice. What is a mushy layer? Dense brine drains convectively from porous mushy sea ice into the ocean. - What is spatial structure of this flow in 3 dimensions? Upper fig.: Sea ice is a porous mixture of solid ice crystals (white) and liquid brine (dark). H. Eicken et al. Cold Regions Science and Technology 31.3 (2000), pp. 207–225 Lower fig.: Trajectory (→) of a solidifying salt water parcel through the phase diagram. As the temperature T decreases, the ice fraction increases and the residual brine salinity SI increases making the fluid denser, which can drive convection. Using a linear approximation for the liquidus curve, the freezing point is - Problem setup Numerically solve mushy-layer equations for porous ice-water Cold upper boundary O matrix g T=-10 C, no normal salt flux, no vertical flow (see appendix). 2m Initial conditions z S=30g/kg O T=Tfreezing (S=30g/kg) + 0.2 C U = 0 Horizontally periodic O y Plus small random O(0.01 C) temperature perturbation x 4m 4m Open bottom boundary Inflow/outflow, with constant pressure O Inflow: S=30g/kg, T=Tfreezing (S=30g/kg) + 0.2 C Movie Contours of: Ice permeability -function of ice porosity; (red lower, green higher ~ice-ocean interface) Velocity (blue lower, purple higher). -

Steven D. Vance –

Steven D. Vance Research Focus My research focuses on using geophysical and geochemical methods to understand ocean worlds: how oceans couple to the thermal evolution and composition, and what this might mean for life. I am also interested in the global geochemical fluxes in ocean worlds, by analogy to biogeochemical fluxes in the Earth system. My experimental research involves collecting thermodynamic equations of state for fluids and ices. I have applied these equations of state to evaluating oceanic heat transport and double diffusive convection in Europa, and to the geophysical constraints imposed by ocean composition on the radial structures of Europa, Ganymede, Callisto, Enceladus, and Titan. In recent years I have used these models to explore the parameter space of possible geophysical signals—seismic, magnetic, and gravitational—in the interest of improving the fidelity of returned science from investigations of ocean composition and habitability. Education 2001–2007 Ph.D., University of Washington, Seattle, Geophysics and Astrobiology. 1996–2000 B.S., University of California, Santa Cruz, Physics (with honors). Ph.D. Thesis title Thesis title: High Pressure and Low Temperature Equations of State for Aqueous Sulfate Solutions: Applications to the Search for Life in Extraterrestrial Oceans, with Particular Reference to Europa advisor Prof. J. Michael Brown Bachelor Thesis title The Role of Methanol Frost in Particle Sticking and the Formation of Planets in the Early Solar Nebula advisor Prof. Frank G. Bridges Current Appointments Research -

I ABSTRACT a CONCEPTUAL MODEL of ICE SHELF

i ABSTRACT A CONCEPTUAL MODEL OF ICE SHELF SEDIMENTATION Matthew Mayerle, M.S. Department of Geology and Environmental Geosciences Northern Illinois University 2014 Ross Powell, Director Sedimentation studies of polar glacimarine systems remain few relative to temperate glacimarine systems due to the problem of accessibility below ice shelves. This thesis presents a conceptual model of ice shelf sedimentation at the scale of a continental shelf, which is an update of Howat and Domack’s (2003) model. This update adds scale, a third dimension, a decade of research on new geologic/glaciological processes, depositional bias', and greater specificity to their model. The shelf-scale model groups facies into deformation till, glacigenic debris flows, shelfstone mud, and diatomaceous mud. Furthermore, the model is tested and shown to be capable of replicating the facies distribution and major landforms found in two distinctly different Antarctic paleo-ice stream troughs within time constraints dictated by radiometric dating. It is hoped that ideas and techniques presented by this conceptual model will serve as a launching pad for more advanced computational models in the future, which are badly needed in order to help constrain future behavior of ice sheets in a warming world. i NORTHERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY DE KALB, ILLINOIS DECEMBER 2014 A CONCEPTUAL MODEL OF ICE SHELF SEDIMENTATION BY MATTHEW WILLIAM MAYERLE ©2014 Matthew Mayerle A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULLFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE DEPARTMENT OF GEOLOGY AND ENVIRONMENTAL GEOSCIENCES Thesis Director: Ross D. Powell ii DEDICATION With love to my parents William and Margaret Mayerle, whose long hours of work provided me with the gift of education. -

Multi-Column Ocean Grid for Ocean Mixing Under Sea Ice in CESM

Multi-column ocean grid for ocean mixing under sea ice in CESM Meibing Jin International Arctic Research Center (IARC) University of Alaska Fairbanks Single column ocean model multi-column ocean model Sea ice Open water Open water model Thick ice Thin ice Thick ice Thin ice Flux i2o Coupler Average flux by ice category Pass Surface layer of ocean model Surface layer of ocean model Ocean vertical mixing: (1) Mixing coef. only (2) Mixing coef. tracer 2-column ocean grid (2cog) experiments scheme Case v0 Case v1 Lead (�↓0 ) Lead (�↓0 ) Ice (�↓1 =1− Ice (�↓1 =1− �↓0 ) �↓0 ) Ocean surface Ocean surface Ocean surface Ocean surface flux F1 flux F0 flux F1 flux F0 Ocean vertical Ocean vertical Ocean vertical Ocean vertical mixing coefficient mixing coefficient mixing coefficient mixing coefficient (VDC1)by KPP (VDC0)by KPP (VDC1)by KPP (VDC0)by KPP Merge (VDC) into single column Ocean implicit Ocean implicit then vertical mixing (T, S) vertical mixing vertical mixing (T1, S1) (T0, S0) Merge (VDC and T, S) into single column Case settings Model: POP-CICE active on GX1 grid CORE 2 forcing data from 1948 to 2009 Parameters are default CESM 1_1_1 setting except: 1) Control case, surface flux (heat and salt) �=�↓0 �↓0 +�↓1 �↓1 2) Case v0 and v1, �↓0 =1−∑↑▒�↓� is lead fraction and�↓1 =1−�↓0 is ice concentration. 3) Case fix, �↓0 is a constant (0.001%) when sea ice present. When �↓0���� =�−�+�↓��_���_��� , the results are almost identical to that of the control. The following discussion, �↓0���� =�−�+�↓��_���_��� , 4) Case n5 is a -

3D Convection, Phase Change, and Solute Transport in Mushy Sea Ice

3D convection, phase change, and solute transport in mushy sea ice Dan Martin, James Parkinson, Andrew Wells, Richard Katz Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (USA), Oxford University (UK). Summary: ● Simulated brine drainage via 3-D convection in porous mushy sea ice ● Shallow region near ice-ocean interface is desalinated by many small brine channels ● Full-depth “mega-channels” allow drainage from saline layer near top of ice. What is a mushy layer? Dense brine drains convectively from porous mushy sea ice into the ocean. - What is spatial structure of this flow in 3 dimensions? Upper fig.: Sea ice is a porous mixture of solid ice crystals (white) and liquid brine (dark). H. Eicken et al. Cold Regions Science and Technology 31.3 (2000), pp. 207–225 Lower fig.: Trajectory (→) of a solidifying salt water parcel through the phase diagram. As the temperature T decreases, the ice fraction increases and the residual brine salinity SI increases making the fluid denser, which can drive convection. Using a linear approximation for the liquidus curve, the freezing point is - Problem setup Numerically solve mushy-layer equations for porous ice-water Cold upper boundary O matrix g T=-10 C, no normal salt flux, no vertical flow (see appendix). 2m Initial conditions z S=30g/kg O T=Tfreezing (S=30g/kg) + 0.2 C U = 0 Horizontally periodic O y Plus small random O(0.01 C) temperature perturbation x 4m 4m Open bottom boundary Inflow/outflow, with constant pressure O Inflow: S=30g/kg, T=Tfreezing (S=30g/kg) + 0.2 C Movie Contours of: Ice permeability -function of ice porosity; (red lower, green higher ~ice-ocean interface) Velocity (blue lower, purple higher). -

Entrainment and Dynamics of Ocean‐Derived Impurities Within Europa's

RESEARCH ARTICLE Entrainment and Dynamics of Ocean‐Derived Impurities 10.1029/2020JE006394 Within Europa's Ice Shell Key Points: J. J. Buffo1,2 , B. E. Schmidt1 , C. Huber3 , and C. C. Walker4 • Planetary ices contain a chemical fingerprint inherited from the 1Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta, GA, USA, 2Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH, USA, 3Brown University, thermochemical properties and 4 dynamics of the parent liquid Providence, RI, USA, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Woods Hole, MA, USA reservoir • The refreezing of basal fractures and perched lenses in Europa's ice Abstract Compositional heterogeneities within Europa's ice shell likely impact the dynamics and shell produces regions of high habitability of the ice and subsurface ocean, but the total inventory and distribution of impurities within the chemical gradation and ‐ concentration shell are unknown. In sea ice on Earth, the thermochemical environment at the ice ocean interface • Europa's ice shell is predicted to governs impurity entrainment into the ice. Here, we simulate Europa's ice‐ocean interface and bound the have a bulk salinity between 1.053 impurity load (1.053–14.72 g/kg [parts per thousand weight percent, or ppt] bulk ice shell salinity) and and 14.72 ppt, depending on the fi ocean composition bulk salinity pro le of the ice shell. We derive constitutive equations that predict ice composition as a function of the ice shell thermal gradient and ocean composition. We show that evolving solidification rates Supporting Information: of the ocean and hydrologic features within the shell produce compositional variations (ice bulk • Supporting Information S1 salinities of 5–50% of the ocean salinity) that can affect the material properties of the ice. -

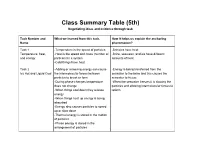

Class Summary Table (5Th) Negotiating Ideas and Evidence Through Task

Class Summary Table (5th) Negotiating ideas and evidence through task Task Number and What we learned from this task. How it helps us explain the anchoring Name phenomenon? Task 1 -Temperature is the speed of particles -Brinicles have heat Temperature, heat, -Heat is the speed and mass (number of -Brine, seawater, and ice have different and energy particles) in a system amounts of heat -Cold things have heat Task 2 -Adding or removing energy can cause -Energy is being transferred from the Icy Hot and Liquid Cool the intermolecular forces between seawater to the brine and this causes the particles to break or form seawater to freeze -During phase changes temperature -When the seawater freezes it is slowing the does not change particles and allowing intermolecular forces to -When things cool down they release reform energy -When things heat up energy is being absorbed -Energy also causes particles to speed up or slow down -Thermal energy is stored in the motion of particles -Phase energy is stored in the arrangement of particles Task 3: -Liquid water is more dense than ice -What ice looks like at the particle level will Water’s Wacky Ways -Water forms hydrogen bonds help with final model -liquid water and solid water look -Ice floats so it can hold the brine on top of different at the particle level the water -Solid water forms hexagon rings -The oxygen have a slightly negative charge, -Surface tension is created by hydrogen while the hydrogens have a slightly positive bonds charge -Cohesion is when particles are attracted to the same type -

Antarctic Dive Guide ASC-17-022 Version 1

Antarctic Dive Guide ASC-17-022 Version 1 July 2017 Antarctic Dive Guide ASC-17-022 Version 1 July 2017 Version History Section Version # Date Author/Editor Change Details (if applicable) This document is derived from a former July Steve Rupp 1 All NSF document, Antarctic Scientific 2017 Dean Hancock Diving Manual (NSF 99-22). The document library holds the most recent versions of all documents. Approved by: Signature Print Name Date Supervisor, Dive Services Approved by: Signature Print Name Date Supervisor, Dive Services All brand and product names remain the trademarks of their respective owners. This publication may also contain copyrighted material, which remains the property of respective owners. Permission for any further use or reproduction of copyrighted material must be obtained directly from the copyright holder. Page i Antarctic Dive Guide ASC-17-022 Version 1 July 2017 Table of Contents Forward ......................................................................................................................... vi 1. Introduction to Antarctic Scientific Diving................................................. 1 2. United States Antarctic Program Scientific Diving Certification ............. 4 2.1. Project Dive Plan Approval ............................................................................ 4 2.2. Diver Certification ........................................................................................... 4 2.3. Pre-Dive Orientation ...................................................................................... -

On the Differing Growth Mechanisms of Black-Smoker and Lost City-Type

On the differing growth rspa.royalsocietypublishing.org mechanisms of black-smoker and Lost City-type hydrothermal vents Research SilvanaS.S.Cardoso1 andJulyanH.E.Cartwright2,3 Cite this article: Cardoso SSS, Cartwright JHE. 2017 On the differing growth mechanisms 1Department of Chemical Engineering and Biotechnology, of black-smoker and Lost City-type Cambridge University, Cambridge CB3 0AS, UK hydrothermal vents. Proc.R.Soc.A473: 2Instituto Andaluz de Ciencias de la Tierra, CSIC–Universidad de 20170387. Granada, 18100 Armilla, Granada, Spain http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rspa.2017.0387 3Instituto Carlos I de Física Teórica y Computacional, Universidad de Granada, 18071 Granada, Spain Received: 12 June 2017 Accepted: 16 August 2017 SSSC, 0000-0003-0417-035X; JHEC, 0000-0001-7392-0957 Black smokers and Lost City-type springs are varieties Subject Areas: of hydrothermal vents on the ocean floors that emit geophysics, fluid mechanics, complexity hot, acidic water and cool, alkaline water, respectively. While both produce precipitation structures as the Keywords: issuing fluid encounters oceanic water, Lost City- chemical gardens, chemobrionics, type hydrothermal vents in particular have been implicated in the origin of life on the Earth. We present hydrothermal vents, origin of life a parallel-velocity flow model for the radius and flow rate of a cylindrical jet of fluid that forms the template Authors for correspondence: for the growth of a tube precipitated about itself and Silvana S. S. Cardoso we compare the solution with previous laboratory e-mail: [email protected] experimental results from growth of silicate chemical gardens. We show that when the growth of the solid Julyan H. -

Water Density

Water Density For most normal substances, as heat is removed from the molecules, they are able to get closer together and become denser. And the solid form is the most dense form. However, water behaves much differently as we know well from having our solid ice cubes float atop our liquid sodas. The solid form of water – ice –is LESS dense than the liquid form Why? The shape of the water molecule of course. As long as water molecules have enough velocity, they can slide in and around each other. However, when they slow down enough, they pack together in a hexagonal structure based on hydrogen bonding. This structure leaves a large hole in the middle of every six water molecules and thus produces a more expanded less dense form. Let’s look at that more closely. Once water cools to very near its freezing temperature (zero degrees), it starts to develop zones of crystals in the hexagonal arrangement previously described – the ones that actually take up more space than the liquid form. When does that start to happen? About 4 degrees Celsius. The result? The liquid starts to expand. The water becomes less dense and rises!. And when, at zero degrees Celsius, it completely freezes, it’s now made up of 100% of that expanded crystal structure, and it is so low density that it floats. This behavior is important for natural freshwater bodies on land. It’s what allows fish to survive winter in the bottom of lakes that are frozen. If ice was denser than water, then lakes would freeze from the bottom upwards, and fish would get frozen out of the lakes. -

From Chemical Gardens to Chemobrionics

From chemical gardens to chemobrionics , , , Laura M. Barge,⇤ † Silvana S. S. Cardoso,⇤ ‡ Julyan H. E. Cartwright,⇤ ¶ , , , Geoffrey J. T. Cooper,⇤ § Leroy Cronin,⇤ § Anne De Wit,⇤ k Ivria J. , , ,# Doloboff,⇤ † Bruno Escribano,⇤ ? Raymond E. Goldstein,⇤ Florence , ,@ , , Haudin,⇤ k David E. H. Jones,⇤ Alan L. Mackay,⇤ 4 Jerzy Maselko,⇤ r , , , Jason J. Pagano,⇤ †† J. Pantaleone,⇤ ‡‡ Michael J. Russell,⇤ † C. Ignacio , , , Sainz-D´ıaz,⇤ ¶ Oliver Steinbock,⇤ ¶¶ David A. Stone,⇤ §§ Yoshifumi , , Tanimoto,⇤ kk and Noreen L. Thomas⇤ ?? Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, California 91109, USA † Department of Chemical Engineering and Biotechnology, University of Cambridge, Cambridge ‡ CB2 3RA, UK Instituto Andaluz de Ciencias de la Tierra, CSIC–Universidad de Granada, E-18100 Armilla, ¶ Granada, Spain WestCHEM School of Chemistry, University of Glasgow, Glasgow G12 8QQ, UK § Nonlinear Physical Chemistry Unit, CP231, Universite´ libre de Bruxelles (ULB), B-1050 k Brussels, Belgium Basque Center for Applied Mathematics, E-48009 Bilbao, Spain ? #Department of Applied Mathematics and Theoretical Physics, University of Cambridge, Cambridge CB3 0WA, UK @Department of Chemistry, University of Newcastle upon Tyne NE1 7RU, UK Birkbeck College, University of London, Malet Street, London WC1E 7HX, UK 4 Department of Chemistry, University of Alaska, Anchorage, Alaska 99508, USA r Department of Chemistry, Saginaw Valley State University, University Center, Michigan †† 48710-0001, USA Department of Physics, University -

CURRICULUM VITÆ Julyan Cartwright

CURRICULUM VITÆ Julyan Cartwright http://www.iact.csic.es/personal/julyan_cartwright Versión de marzo de 2019 1 CURRICULUM VITAE APELLIDO: Cartwright NOMBRES: Julyan Harold Edward FECHA DE NACIMIENTO: 4 Agosto 1967 NACIONALIDAD: Británica NIE: X1656430Q (España) SEXO: Varón TEL.: 609 355224 FORMACION ACADEMICA LICENCIATURA: (Homologada en España) Licenciado en Física Teorica University of Newcastle upon Tyne, Gran Bretaña Título de tesina: The Spherical Pendulum Revisited: Chaos in a Forced Oscillator DIRECTOR DE TESINA: Dr. David J. Tritton FECHA: Junio 1988 DOCTORADO: (Homologado en España) Doctor en Matematica Aplicada University of London, Gran Bretaña Título de tesis: Chaos in Dissipative Systems: Bifurcations and Basins DIRECTOR DE TESIS: Dr. David K. Arrowsmith FECHA: Octubre 1992 SITUACION PROFESIONAL: Científico Titular del CSIC (cuatro sexenios; cinco quinquenios) y Miembro del Instituto Carlos I de Física Teórica y Computacional, Universidad de Granada. INSTITUTO: Instituto Andaluz de Ciencias de la Tierra (CSIC–UGR) DIRECCION POSTAL: E-18100 Armilla, Granada. CORREO ELECTRONICO: [email protected] WWW http://www.iact.csis.es/personal/julyan_cartwright DEDICACION: A tiempo completo ACTIVIDADES ANTERIORES DE CARACTER CIENTIFICO FECHAS PUESTO INSTITUCION Mar 00 Científico Titular; antes Consejo Superior de Investigaciones — presente ‘Ramón y Cajal’ Fellow Científicas (CSIC), España. Nov 15 Miembro Instituto Carlos I de Física Teórica y — presente Computacional, Universidad de Granada. May 14 Visiting Scholar Pembroke College, — May 15 Cambridge University, UK. Nov 99 Visiting Scholar Lawrence Livermore Natl Laboratory, — Sep 01 University of California, USA. Nov 98 Profesor Visitante Universidad de Granada y — Feb 00 Universidad de las Islas Baleares, España Ene 98 Profesor Visitante Bioengineering Institute & Dept of Physics, — Oct 98 Miguel Hernández University, España.