Resilient Podcast, Episode 2, May 2016.Docx

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Special Orders

SPECIAL ORDERS Automobile Care/Gas Cards National Restaurants Acapulco Mexican Restaurante $25.00 @ 9.00% 76® Gas $100.00 @ 1.50% Applebee's $25.00 @ 8.00% 76® Gas $50.00 @ 1.50% Arby's $10.00 @ 8.00% Advance Auto $500.00 @ 7.00% Arby's $50.00 @ 8.00% Advance Auto Parts $25.00 @ 7.00% Black Angus Steakhouse $25.00 @ 11.00% Arco Gas Stations $100.00 @ 1.50% Bob Evans Restaurants® $20.00 @ 10.00% Arco Gas Stations $250.00 @ 1.50% Buca di Beppo $25.00 @ 8.00% Arco Gas Stations $50.00 @ 1.50% BufFalo Wild Wings $10.00 @ 8.00% AutoZone $25.00 @ 8.00% BufFalo Wild Wings $25.00 @ 8.00% Chevron Gas $100.00 @ 1.00% Burger King $10.00 @ 4.00% Chevron Gas $250.00 @ 1.00% Burger King $50.00 @ 4.00% Chevron Gas $50.00 @ 1.00% CaliFornia Pizza Kitchen $25.00 @ 8.00% Circle K $100.00 @ 1.50% Carl's Jr $10.00 @ 5.00% Circle K $25.00 @ 1.50% Carrabba's Italian Grill $25.00 @ 8.00% Exxon $100.00 @ 1.00% Carrabba's Italian Grill $50.00 @ 8.00% Exxon $50.00 @ 1.00% Cheesecake Factory $25.00 @ 5.00% Jiffy Lube $25.00 @ 8.00% Chevys Fresh Mex $25.00 @ 9.00% Mobil $100.00 @ 1.00% Chili's $25.00 @ 10.00% Mobil $50.00 @ 1.00% Chili's $50.00 @ 10.00% Shell Gas $100.00 @ 1.50% Chipotle $10.00 @ 11.00% Shell Gas $25.00 @ 1.50% Chipotle $25.00 @ 11.00% Shell Gas $50.00 @ 1.50% Chuck E. -

Krispy Kreme Doughnuts®

® www.krispykreme.com Krispy Kreme Doughnuts Brands are trademarks of their respective holders. Food Item Serving Weight Calories Carbs Fiber Protein Fat % Cals Saturated Trans Cholesterol Sodium (g) (g) (g) (g) (g) from Fat Fat (g) Fat (g) (mg) (mg) Doughnuts Apple Fritter 87 210 18 1 3 14 60 7 0 5 110 Baseball Doughnut 68 290 33 <1 4 17 53 8 0 0 125 Caramel Kreme Crunch 96 390 50 <1 4 20 46 10 0 5 170 Chocolate Iced Cake 71 280 34 <1 3 15 48 7 0 20 320 Chocolate Iced Custard Filled 89 310 36 <1 4 17 49 8 0 0 150 Chocolate Iced Glazed 64 240 33 <1 2 11 41 5 0 5 95 Chocolate Iced Glazed Cruller 70 260 38 <1 2 12 42 5 0 15 260 Chocolate Iced Glazed Football Stamp 72 290 31 <1 4 17 53 8 0 0 125 Chocolate Iced Glazed Hearts w/Strawberry - Kreme Filling and Red Drizzle 93 360 43 <1 4 20 50 10 0 0 150 Chocolate Iced Kreme Filling 89 360 40 <1 4 21 53 10 0 0 140 Chocolate Iced Kreme Filling Web (Halloween) 100 400 51 <1 4 20 45 10 0 0 140 Chocolate Iced Glazed w/ Sprinkles 72 270 41 <1 2 11 37 5 0 5 95 Chocolate Iced Raspberry Filled 89 310 36 <1 4 17 49 8 0 0 125 Cinnamon Apple Filled 81 290 33 <1 3 16 50 8 0 5 150 Cinnamon Bun 67 260 28 <1 3 16 55 8 0 5 125 Cinnamon Twist 59 240 23 <1 3 15 56 7 0 5 130 Doughnut Hole Glazed Blueberry Cake 4 Holes 51 190 26 <1 2 8 38 4 0 15 210 Doughnut Hole Glazed Cake 4 Holes 51 200 26 <1 2 10 45 4.5 0 15 220 Doughnut Hole Glazed Chocolate Cake 4 Holes 51 190 25 1 2 9 43 4.5 0 15 200 Doughnut Hole Original Glazed 4 Holes 54 200 26 0 2 11 50 4.5 0 0 90 Doughnut Hole Pumpkin Spice 4 Holes 51 210 29 0 2 10 43 -

How Krispy Kremes Work

How Krispy Kremes Work by Tom Harris In the southern United States, sweets fans have been scarfing down Krispy Kreme doughnuts for more than 50 years -- in many families, they're a weekly ritual! The rest of the country finally got 1 a taste in the '90s, when Krispy Kreme launched new doughnut stores coast to coast, to much fanfare. The company's unique snacks have also crept into pop culture over the past few years, appearing in several TV shows and in dozens of national magazines. On top of that, Krispy Kreme has been making headlines in the financial world -- it was one of the best performing initial public offering stocks in 2000. All this, as well as some grumbling stomachs, seemed like a good excuse to stop by our local Krispy Kreme for a peek behind the scenes. In this edition of HowStuffWorks, we'll see how the Raleigh, NC, "factory store" transforms raw ingredients into Krispy 2 Kreme's signature doughnut, the "original glazed." We'll also see how the store's doughnut-makers get chocolate filling in the middle of doughnuts, and find out a little bit about Krispy Kreme's distribution structure. Mixing and Extruding The Raleigh Krispy Kreme is one of Krispy Kreme's many factory stores, bakeries that make doughnuts for walk-in customers as well as for local grocery stores. All the factory store's 3 ingredients are prepared in a Krispy Kreme manufacturing facility in Winston Salem, about two hours away. In the factory store back room, we found stacks of doughnut mix, sugar, yeast, doughnut filling and other packaged ingredients. -

2011 Veteran's Day Free Meals and Discounts

2011 Veteran’s Day Free Meals and Discounts by Ryan Guina on October 23, 2011 Veteran’s Day is soon approaching and there are many restaurants and companies who want to thank our veterans by providing them with discounts or a free meal. To those companies offering veterans a free meal or discount, the military community gives a collective thanks! Our goal is to share as many of these free meals and discounts with our military veterans and we will update this page as soon as new information becomes available. 2011 Veteran’s Day Free Meals and Discounts Two notes before jumping in: Proof of Military Service. First, most companies require some form of military ID – including a U.S. Uniform Services ID Card (active/reserve/retired), Current Leave and Earnings Statement (LES), Photograph in uniform, be wearing uniform (if your service permits), Veterans Organization Card (e.g., American Legion and VFW), DD214, discharge paperwork, or other form of identification. Other restaurants and companies may only require a photo of you in uniform, or go by the honor system. Participation. Second, always call ahead to verify locations, times, and participation. Many of the listed companies are franchises and may have different policies. We will do our best to keep this page updated as we find new info. 2011 Free Veterans Day Meals Applebee’s – free meal, Friday, Nov. 11: Last year, Applebee’s served 1,024,000 million free meals to military veterans and active servicemembers. Applebee’s is again offering a free meal to military veterans and active-duty service members on Veteran’s Day, Friday, Nov. -

MAPB Public Expose Presentation, 19 August 2021

Public Expose PRESENTATION BY ANTHONY Cottan PRESIDENT DIRECTOR JAKarta, AUGUst 19TH 2021 1 Contents • MBA Overview • 2020 Financial Highlights • 2020 Marketing & Operational Highlights • 2020: How We Reimagined MBA • Looking Ahead: Roadmap to 2023 • ESG 2 MBA Overview (End June 2021) 593 7PremiuM 5,499 REtAiL StORES F&B BrandS employEES LiStEd On A member of MAp group 33 indOnESiA StrategiC pARtnERSHip WitH CitiES StOCk ExCHAnGE GEneral atlantiC 3 MBA Overview (End June 2021) 478 stores 20 stores 5 stores 22 stores 32 stores 29 stores 7 stores TotAL 593 stores 4 2020 FinAnCial HiGHLiGHtS 5 Consolidated income Statement Consolidated Un-audited Audited (IDR Million) 1H 21 Q1 21 2020 2019 2018 NET SALES 1,176,010 551,637 2,044,306 3,094,880 2,576,852 % growth 22.5% -18.6% -33.9% 20.1% 22.6% E B I T D A 254,253 100,967 401,699 457,224 353,724 % margin 21.6% 18.3% 19.6% 14.8% 13.7% % growth 61.4% -34.9% -12.1% 29.3% 15.5% E B I T (8,951) (25,010) (152,581) 223,478 162,251 % margin -0.8% -4.5% -7.5% 7.2% 6.3% % growth 92.8% -306.6% -168.3% 37.7% 2.8% NET INCOME/(LOSS) (20,068) (22,828) (164,799) 165,726 110,688 % margin -1.7% -4.1% -8.1% 5.4% 4.3% % growth 82.5% -48.0% -199.4% 49.7% 20.5% Figures presented for 1H2021, Q12021 and 2020 are after PSAK 73 6 Operating Expenses Efficiency OPERATING EXPENSES Efficiency in 2020 1H 2021 2020 (GROWTH VS 2019) total payroll Saving: Rp 152,975 M PREMISES COST -29.7% -32.7% total Efficiency premises Cost Saving: Rp 133,982 M PAYROLL -18.0% -22.5% DEPRE & AMORTISATION 14.1% 13.9% Efficiency in 2021 A &P -

Free Meals, Activities & Discounts for Veterans Day 2011 This List Is For

Free Meals, Activities & Discounts for Veterans Day 2011 This list is for informative purposes only and does not constitute an endorsement or recommendation by the United States Department of Veterans Affairs. The United States does not warrant or guarantee the products, services or information provided. Applebee’s – free meal, Friday, Nov. 11: Applebee’s is offering a free meal to military veterans and active-duty service members on Veteran’s Day, Friday, Nov. 11, 2011. There will be 7 entrées to choose from. Military ID or proof of service required. Find locations at http://applebees.com/. Chili’s – free meal, Friday, Nov. 11. Chili’s is offering all military veterans past and present their choice of one of 6 meals. This offer is available during business hours on November 11, 2011 at participating Chili’s in the U.S. only. Dine-in from limited menu only; beverages and gratuity not included. Veterans and active duty military simply show proof of military service. Visit their website to find locations: http://www.chilis.com/EN/Pages/home.aspx. Golden Corral – Free meal, Monday Nov. 14: The 10th annual Golden Corral Military Appreciation dinner will be held on Monday, November 14, 2011 from 5 p.m. to 9 p.m. in all Golden Corral Restaurants nationwide. The free “thank you” dinner is available to any person who has ever served in the United States Military. If you are a veteran, retired, currently serving, in the National Guard or Reserves, you are invited to participate in Golden Corral’s Military Appreciation Monday dinner. For more information visit http://www.goldencorral.com/military/. -

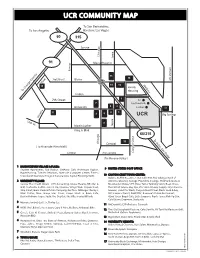

Ucr Community Map

UCR COMMUNITY MAP To San Bernardino, To Los Angeles Barstow, Las Vegas 60 215 Spruce Chicago Iowa 91 Massachusetts Kansas 13 16 3rd Street Blaine Mt.Vernon Vine 14 15 Watkins 12 Family To Orange County Housing Linden Canyon Crest 7th Street 1 A-I 7 Pentland Hills University 5 2 Lothian 17 11 4 3 8 6 UCR Big SpringsSprings Victoria 14th St. 9 Martin Luther Iowa King Jr. Blvd 60/215 To Indio, San Diego 10 Chicago Central ( To Riverside Plaza Mall ) Central Alessandro Canyon CrestCrest ( To Moreno Valley ) 1 BANNOCKBURN VILLAGE & PLAZA: Student Apartments, Sub-Station, GetAway Cafe, Archetype, Kaplan, 9 UNITED STATES POST OFFICE Hyperlearning, Transfer Relations, Riverside Computer Center, Fitness United with Nutrition, Design & Construction, Capital Planning, CLIFS 10 CANYON CREST TOWN CENTER: Ralphs, Coee Roasters, Crest Cafe, Rite Aid, Subway, Bank of 2 UNIVERSITY VILLAGE: America, Downey Savings, Provident Savings, Hallmark, Donuts, Service Plus Credit Union, UCR Accounting, Movie Theatre, BB’s Bar & Blockbuster Video, UPS Store, Tailor, Tanning Salon, Book Store, Grill, Starbuck's Coee, Juice It Up, Quiznos, Village Wok, Teriyaki Bowl, Hair & Nail Salons, Day Spa, Pet Store, Beauty Supply, Dry Cleaners, Ship Smart, Great Steak & Potato Company, Del Taco, FatBurger, Denny's, Jeweler, Hand Car Wash, Canyon Crest Travel, Don's Lock & Key, Mad Platter, New Image Hair Salon, Crepe Shack & Boba Cafe, Ritz Camera, Florist, A&W/KFC, Romano's Italian Restaurant, Baskin-Robbins, Togos, Sushi, The DogOut, The Ville, Tropics Billiards 42nd Street -

The History of Krispy Kreme

Thank you for your interest in Krispy Kreme. Krispy Kreme History 1933 In 1933, Vernon Carver Rudolph, the founder of Krispy Kreme, bought a doughnut shop in Paducah, Kentucky, from a French chef from New Orleans. He received the company’s assets, goodwill, and the rights to a secret yeast-raised doughnut recipe. Mid 1930s It wasn’t long before Rudolph and his partner decided to look for a larger market. They moved their operations to Nashville, Tennessee, where other members of the Rudolph family joined the business and opened shops in Charleston, West Virginia; and Atlanta, Georgia. At this time, the business focused on selling doughnuts to local grocery stores. July 13, 1937 During the early summer of 1937, Rudolph decided to leave Nashville to open his own doughnut shop. He and two other young men set off in a 1936 Pontiac and arrived in Winston-Salem with $25 in cash, a few pieces of doughnut-making equipment, the secret recipe, and the name Krispy Kreme Doughnuts. They used their last $25 to rent a building across from Salem Academy and College in what is now called historic Old Salem. With little money left to buy ingredients, Rudolph convinced a nearby grocer to lend him ingredients in return for payment once the first doughnuts were sold. Next, Rudolph needed a way to deliver the doughnuts. So he took the back seat out of the Pontiac and installed a delivery rack. On July 13, 1937, the first Krispy Kreme doughnuts were made and sold at the new Winston-Salem shop. -

SURVEY ANALYSIS Pg. 3 # WINNING BRANDS Pg. 22 # SEGMENT

WWW.NRN.COM MARCH 24, 2014 A PENTON© PUBLICATION SURVEY ANALYSIS pg. 3 l WINNING BRANDS pg. 22 l SEGMENT RANKINGS pg. 24 Saving with sustainability pg. 52 • Restaurants, suppliers co-brand pg. 58 • Wendy’s marketing success pg. 68 WWW.NRN.COM MARCH 24, 2014 A PENTON© PUBLICATION PAGE 3 THE CHEESECAKE FACTORY’S CAJUN JAMBALAYA PASTA See which brands win diners’ devotions and why in the fourth annual survey BY ROBIN LEE ALLEN desires and rewarding brands that listen to their preferences. Three IN-N-OUT BURGER’S estaurants have questioned out of the four top-performing DOUBLE-DOUBLE CHEESEBURGER and studied for years the im- brands in their respective Con- Rpacts the Millennial age group sumer Picks restaurant industry will have on their businesses — segments — In-N-Out Burger RUTH’S CHRIS STEAK HOUSE’S THE ORIGINAL PANCAKE HOUSE’S and the answers have arrived. in Limited Service, The Original HERO RIBEYE APPLE PANCAKES In the fourth annual Consumer Pancake House in Family Dining Picks survey from Nation’s Res- and Ruth’s Chris Steak House in taurant News and WD Partners, Fine Dining — were buoyed by the rising importance of peer or high scores in many attributes, but social reviews, best tied to survey most importantly in Likely to Rec- attributes Likely to Recommend ommend. Many of the highest- and Likely to Return, showcase the ranking brands within the report’s dominant nature of sharing among subsegments, like Limited-Service Millennials. Beverage/Snack or Casual-Dining With the bulk of the estimated Italian/Pizza, also scored high in 90 million people born between Likely to Recommend. -

Edinburg Restaurant Market Potential

Restaurant Market Potential Shoppes at Rio Grande Valley Prepared by The Canvass Group 419 E Trenton Rd, Edinburg, Texas, 78539 Latitude: 26.26144 Drive Time: 5 minute radius Longitude: -98.16832 Demographic Summary 2018 2023 Population 19,833 22,345 Population 18+ 13,885 15,644 Households 5,697 6,433 Median Household Income $50,230 $58,724 Expected Number of Product/Consumer Behavior Adults Percent MPI Went to family restaurant/steak house in last 6 mo 10,854 78.2% 104 Went to family restaurant/steak house 4+ times/mo 3,884 28.0% 104 Spent at family restaurant/30 days: <$31 1,082 7.8% 89 Spent at family restaurant/30 days: $31-50 1,532 11.0% 111 Spent at family restaurant/30 days: $51-100 2,323 16.7% 108 Spent at family restaurant/30 days: $101-200 1,476 10.6% 114 Spent at family restaurant/30 days: $201-300 356 2.6% 103 Family restaurant/steak house last 6 months: breakfast 2,059 14.8% 111 Family restaurant/steak house last 6 months: lunch 3,135 22.6% 116 Family restaurant/steak house last 6 months: dinner 6,617 47.7% 102 Family restaurant/steak house last 6 months: snack 410 3.0% 150 Family restaurant/steak house last 6 months: weekday 4,097 29.5% 96 Family restaurant/steak house last 6 months: weekend 6,378 45.9% 108 Fam rest/steak hse/6 months: Applebee`s 2,713 19.5% 87 Fam rest/steak hse/6 months: Bob Evans Farms 265 1.9% 52 Fam rest/steak hse/6 months: Buffalo Wild Wings 1,802 13.0% 124 Fam rest/steak hse/6 months: California Pizza Kitchen 342 2.5% 88 Fam rest/steak hse/6 months: Carrabba`s Italian Grill 591 4.3% 141 Fam rest/steak -

Muis Halal Certified Eating Establishments NOT for COMMERCIAL USE

Muis Halal Certified Eating Establishments NOT FOR COMMERCIAL USE MUIS HALAL CERTIFIED EATING ESTABLISHMENTS (1) Click on "Ctrl + F" to search for the name or address of the establishment. (2) You are advised to check the displayed Halal certificate & ensure its validity before patronising any establishment. (3) For updates, please visit www.halal.sg. Alternatively, you can contact Muis at tel: 6359 1199 or email: [email protected] Last Updated: 16 Oct 2018 COMPANY / EST. NAME ADDRESS POSTAL CODE 126 CONNECTION BAKERY 45 OWEN ROAD 01-297 - 210045 SEMBAWANG SPRINGS 13 MILES 596B SEMBAWANG ROAD - 758455 ESTATE 149 Cafe @ TechnipFMC (Mngd By 149 GUL CIRCLE - - 629605 The Wok People) REPUBLIC POLYTECHNIC 1983 A Taste of Nanyang E1 WOODLANDS AVENUE 9 02 738964 (Food Court A) SINGAPORE MANAGEMENT 1983 A Taste of Nanyang 70 STAMFORD ROAD 01-21 178901 UNIVERSITY 1983 A Taste of Nanyang 2 Ang Mo Kio Drive 02-10 ITE College Central 567720 CHANGI AIRPORT 1983 Cafe Nanyang 60 AIRPORT BOULEVARD 026-018-09 819643 TERMINAL 2 HARBOURFRONT CENTRE, 1983 Coffee & Toast 1 MARITIME SQUARE 02-21 099253 TRANSIT AREA Tower C, Jurong Community 1983 Coffee & Toast - 1 Jurong East Street 21 01-01 609606 Hospital 1983 Coffee & Toast 1 JOO KOON CIRCLE 02-32/33 FAIRPRICE HUB 629117 CHANGI GENERAL 1983 Coffee & Toast 2 SIMEI STREET 3 01-09/10 529889 HOSPITAL 21 On Rajah 1 JALAN RAJAH 01 DAYS HOTEL 329133 4 Fingers Crispy Chicken 2 ORCHARD TURN B4-06/06A ION ORCHARD 238801 4 Fingers Crispy Chicken 68 ORCHARD ROAD B1-07 PLAZA SINGAPURA 238839 4 Fingers Crispy Chicken 1 -

Guide to the Krispy Kreme Corporation Records

Guide to the Krispy Kreme Corporation Records NMAH.AC.0594 Juliette Arai October 1998 Archives Center, National Museum of American History P.O. Box 37012 Suite 1100, MRC 601 Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 [email protected] http://americanhistory.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 5 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 9 Container Listing ........................................................................................................... 11 Series 1: History of Krispy Kreme, 1948-1952....................................................... 11 Series 2: Administrative Records, 1939-1997........................................................ 12 Series 3: Operational Records, 1947-2009............................................................ 16 Series 4: Newsletters, 1957-1998.......................................................................... 24 Series 5: Press Clippings, 1949-1998, 2000.......................................................... 25