Pohlman Sbts 0207D 10063.Pdf (1.129Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Free Methodist Church, the Wesleyan Methodist Church, the Salvation Army and the Church of the Nazarene)

A Study of Denominations 1 Corinthians 14:33 (KJV 1900) - 33 For God is not the author of confusion, but of peace, as in all churches of the saints. Holiness Churches - Introduction • In historical perspective, the Pentecostal movement was the child of the Holiness movement, which in turn was a child of Methodism. • Methodism began in the 1700s on account of the teachings of John and Charles Wesley. One of their most distinguishing beliefs was a distinction they made between ordinary and sanctified Christians. • Sanctification was thought of as a second work of grace which perfected the Christian. Also, Methodists were generally more emotional and less formal in their worship. – We believe that God calls every believer to holiness that rises out of His character. We understand it to begin in the new birth, include a second work of grace that empowers, purifies and fills each person with the Holy Spirit, and continue in a lifelong pursuit. ―Core Values, Bible Methodist Connection of Churches • By the late 1800s most Methodists had become quite secularized and they no longer emphasized their distinctive doctrines. At this time, the "Holiness movement" began. • It attempted to return the church to its historic beliefs and practices. Theologian Charles Finney was one of the leaders in this movement. When it became evident that the reformers were not going to be able to change the church, they began to form various "holiness" sects. • These sects attempted to return to true Wesleyan doctrine. Among the most important of these sects were the Nazarene church and the Salvation Army. -

![The Charismatic Movement and Lutheran Theology [1972]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7475/the-charismatic-movement-and-lutheran-theology-1972-67475.webp)

The Charismatic Movement and Lutheran Theology [1972]

THE CHARISMATIC MOVEMENT AND LUTHERAN THEOLOGY Pre/ace One of the significant developments in American church life during the past decade has been the rapid spread of the neo-Pentecostal or charis matic movement within the mainline churches. In the early sixties, experi ences and practices usually associated only with Pentecostal denominations began co appear with increasing frequency also in such churches as the Roman Catholic, Episcopalian, and Lutheran. By the mid-nineteen-sixties, it was apparent that this movement had also spread co some pascors and congregations of The Lutheran Church - Missouri Synod. In cerrain areas of the Synod, tensions and even divisions had arisen over such neo-Pente costal practices as speaking in tongues, miraculous healings, prophecy, and the claimed possession of a special "baptism in the Holy Spirit." At the request of the president of the Synod, the Commission on Theology and Church Relations in 1968 began a study of the charismatic movement with special reference co the baptism in the Holy Spirit. The 1969 synodical convention specifically directed the commission co "make a comprehensive study of the charismatic movement with special emphasis on its exegetical aspects and theological implications." Ie was further suggested that "the Commission on Theology and Church Relations be encouraged co involve in its study brethren who claim to have received the baptism of the Spirit and related gifts." (Resolution 2-23, 1969 Pro ceedings. p. 90) Since that time, the commission has sought in every practical way co acquaint itself with the theology of the charismatic movement. The com mission has proceeded on the supposition that Lutherans involved in the charismatic movement do not share all the views of neo-Pentecostalism in general. -

"How to Use the Bible in Modern Theological Construction" The

Christ. Rather than being the Judge, Chirst is the light in 23 Nov which we pass judgment on ourselves. The truth is that 1949 everyday our deeds and words, our silence and speech, are building character. Any day that reveals this fact is a day of judgment. THDS. MLKP-MBU: Box I 13, folder 19. The Martin Luther King, Jr. Papers Project "How to Use the Bible in Modern Theological Construction" [13September-23 November 19491 [Chester, Pa.] In this paper written for Christian Theologyfor Today, King directly confronts a question many of his earlier papers had skirted: how does one reconcile the Bible with science? King finds a solution by following the example of biblical critics such as Millar Burrows and Harry Emerson Fosdick.' He defines their approach: "It sees the Bible not as a textbook written with divine hands, but as a portrayal of the experiences of men written in particular historical situations," so "that God reveals himself progressively through human history, and that the final signijicance of the Scripture lies in the outcome of the process." Davh gave the paper an A - and wrote: "I think you could be more pointed injust how you apply progressive revelation to theological construction. Nonetheless, you do a good piece of work and show that you have grasped the theological significance of biblical criticism." The question as to the use of the Bible in modern culture stands as a perplexing enigma troubling mul- titudes of minds. As modern man walks through the pages of this sacred book he is constantly hindered by numerous obstacles standing in his path. -

The Musical Heritage of the Lutheran Church Volume I

The Musical Heritage of the Lutheran Church Volume I Edited by Theodore Hoelty-Nickel Valparaiso, Indiana The greatest contribution of the Lutheran Church to the culture of Western civilization lies in the field of music. Our Lutheran University is therefore particularly happy over the fact that, under the guidance of Professor Theodore Hoelty-Nickel, head of its Department of Music, it has been able to make a definite contribution to the advancement of musical taste in the Lutheran Church of America. The essays of this volume, originally presented at the Seminar in Church Music during the summer of 1944, are an encouraging evidence of the growing appreciation of our unique musical heritage. O. P. Kretzmann The Musical Heritage of the Lutheran Church Volume I Table of Contents Foreword Opening Address -Prof. Theo. Hoelty-Nickel, Valparaiso, Ind. Benefits Derived from a More Scholarly Approach to the Rich Musical and Liturgical Heritage of the Lutheran Church -Prof. Walter E. Buszin, Concordia College, Fort Wayne, Ind. The Chorale—Artistic Weapon of the Lutheran Church -Dr. Hans Rosenwald, Chicago, Ill. Problems Connected with Editing Lutheran Church Music -Prof. Walter E. Buszin The Radio and Our Musical Heritage -Mr. Gerhard Schroth, University of Chicago, Chicago, Ill. Is the Musical Training at Our Synodical Institutions Adequate for the Preserving of Our Musical Heritage? -Dr. Theo. G. Stelzer, Concordia Teachers College, Seward, Nebr. Problems of the Church Organist -Mr. Herbert D. Bruening, St. Luke’s Lutheran Church, Chicago, Ill. Members of the Seminar, 1944 From The Musical Heritage of the Lutheran Church, Volume I (Valparaiso, Ind.: Valparaiso University, 1945). -

THE MISSIONARY SPIRIT in the AUGUSTANA CHURCH the American Church Is Made up of Many Varied Groups, Depending on Origin, Divisions, Changing Relationships

Augustana College Augustana Digital Commons Augustana Historical Society Publications Augustana Historical Society 1984 The iM ssionary Spirit in the Augustana Church George F. Hall Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.augustana.edu/ahsbooks Part of the History Commons, and the Scandinavian Studies Commons Recommended Citation "The iM ssionary Spirit in the Augustana Church" (1984). Augustana Historical Society Publications. https://digitalcommons.augustana.edu/ahsbooks/11 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Augustana Historical Society at Augustana Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Augustana Historical Society Publications by an authorized administrator of Augustana Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Missionary Sphit in the Augustana Church George F. Hall \ THE MISSIONARY SPIRIT IN THE AUGUSTANA CHURCH The American church is made up of many varied groups, depending on origin, divisions, changing relationships. One of these was the Augustana Lutheran Church, founded by Swedish Lutheran immigrants and maintain ing an independent existence from 1860 to 1962 when it became a part of a larger Lutheran community, the Lutheran Church of America. The character of the Augustana Church can be studied from different viewpoints. In this volume Dr. George Hall describes it as a missionary church. It was born out of a missionary concern in Sweden for the thousands who had emigrated. As soon as it was formed it began to widen its field. Then its representatives were found in In dia, Puerto Rico, in China. The horizons grew to include Africa and Southwest Asia. Two World Wars created havoc, but also national and international agencies. -

Literary Criticism from a Cape Town Pulpit: Ramsden Balmforth's

In die Skriflig / In Luce Verbi ISSN: (Online) 2305-0853, (Print) 1018-6441 Page 1 of 7 Original Research Literary criticism from a Cape Town pulpit: Ramsden Balmforth’s explications of modern novels as parables revealing ethical and spiritual principles Author: Literary criticism evolved slowly in southern Africa. One of the first commentators to write 1 Frederick Hale about this topic was the Unitarian minister, Ramsden Balmforth (1861-1941), a native of Affiliation: Yorkshire and Unitarian minister who emigrated to Cape Town in 1897. Eschewing conventional 1Research Unit for Reformed homiletics in its various forms, in dozens of instances he illustrated ethical and spiritual points Theology, Faculty of in his Sunday sermons or ‘discourses’ by discussing their manifestation in literary works. Theology, North-West Crucially, these texts did not merely yield illustrations of Biblical themes, but themselves University, South Africa served as the primary written vehicles of moral and ethical principles, and the Bible was rarely Corresponding author: mentioned in them. Balmforth’s orations about novels were published in 1912. The following Frederick Hale, year he preached about selected operas by Richard Wagner, and in the 1920s Balmforth issued [email protected] two additional series of discourses focusing on dramas. In all of these commentaries he Dates: consistently emphasised thematic content rather than narrative and other literary techniques. Received: 29 July 2016 He extracted lessons which he related to his ethically orientated version of post-orthodox Accepted: 21 Apr. 2017 religious faith. Published: 27 July 2017 How to cite this article: Hale, F., 2017, ‘Literary Introduction criticism from a Cape Town pulpit: Ramsden Balmforth’s The phenomenon of preaching has hardly been an unexplored topic in the history of Christianity. -

Pastor's Pondering ̴

Spire Barre Congregational Church, UCC Welcoming & Serving the Quabbin Area Phone—978-355-4041 Email—[email protected] website—www.barrechurch.com ̴ Pastor’s Pondering ̴~ Instead, speaking the truth in love, we will grow to become in every respect t he mature body of him who is the head, that is, Christ. ~ (Ephesians 4:15) On Sunday, September 27, a majority of the voting members present at the special congregational meet- ing accepted the six recommendations of the MACUCCC to help resolve “conflict and the financial sit- uation.” In her introduction to the recommendations, MACUCC Associate Conference Minister Rev. Kelly Gal- lagher stated: “It is clear from the conversations with groups within the church that there is a history of conflict and lack of communication within the congregation. Much like many congregations, this con- flict often surfaces around finances and change. There appears to be need for structural accountability and transparency throughout the governance of the church.” In her comments to those in attendance Sunday, she observed that the institutional church has not kept pace with the changes that have taken place in the world over the last 5 or 6 decades, and that we, like many other MA congregations need to review all aspects of our organizational structure so that we can continue to faithfully respond to the needs of our neighbors in this time. We know that the process itself will generate moments of disagreement, confusion, and a temporary sense of disorientation. However, the goals of this process are to clarify our sense of mission in response to God’s call, to identify the gifts for ministry within our own congregation and to maximize their effectiveness in ways that may bear no resemblance to how we’ve always done things. -

Pentecostal and Charismatic Movements Don Fanning Liberty University, [email protected]

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Liberty University Digital Commons Liberty University DigitalCommons@Liberty University Trends and Issues in Missions Center for Global Ministries 2009 Pentecostal and Charismatic Movements Don Fanning Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/cgm_missions Recommended Citation Fanning, Don, "Pentecostal and Charismatic Movements" (2009). Trends and Issues in Missions. Paper 7. http://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/cgm_missions/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for Global Ministries at DigitalCommons@Liberty University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Trends and Issues in Missions by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Liberty University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Pentecostal/Charismatic Movements Page 1 Pentecostal Movement The first two hundred years (100-300 AD) The emphasis on the spiritual gifts was evident in the false movements of Gnosticism and in Montanism. The result of this false emphasis caused the Church to react critically against any who would seek to use the gifts. These groups emphasized the gift of prophecy, however, there is no documentation of any speaking in tongues. Montanus said that “after me there would be no more prophecy, but rather the end of the world” (Philip Schaff, History of the Christian Church, Vol II, p. 418). Since his prophecy was not fulfilled, it is obvious that he was a false prophet (Deut . 18:20-22). Because of his stress on new revelations delivered through the medium of unknown utterances or tongues, he said that he was the Comforter, the title of the Holy Spirit (Eusebius, V, XIV). -

CH510: a History of the Charismatic Movements Course Lecturer: John D

COURSE SYLLABUS CH510: A History of the Charismatic Movements Course Lecturer: John D. Hannah, PhD, ThD Distinguished Professor of Historical Theology at Dallas Theological Seminary About This Course This course was originally created through the Institute of Theological Studies in association with the Evangelical Seminary Deans’ Council. There are nearly 100 evangelical seminaries of various denominations represented within the council and many continue to use the ITS courses to supplement their curriculum. The lecturers were selected primarily by the Deans’ Council as highly recognized scholars in their particular fields of study. Course Description Charismatic theology is more than just a theology of spiritual gifts; worship, bibliology, sanctification, and ecclesiology are also central. Learners will complete a historical and theological study of the origins and developments of Classical Pentecostalism, Charismatic Renewalism, and Restoration Movements, with emphasis given to theological backgrounds and trends. Lectures also analyze other related movements, including the Jesus Only Movement, the Vineyard Movement, and the Toronto Revival Movement. Throughout the course, the pros and cons of the various charismatic movements are presented. Course Objectives Upon completion of the course, the student should be able to do the following: • Trace the history of the Pentecostal Movement from its origin in the American Holiness Movement to its current manifestation, Charismatic Renewalism, and the varieties of Restorationism. • Move toward a formulation (or clearer understanding) of such concepts as spiritual power and victory for himself/herself. At the minimum, the course purposes to discover the questions that must be asked in order to formulate a cogent statement of the “victorious Christian life.” • Gain insight into the nature and defense of Pentecostal and Charismatic distinctives, as well as the theological changes that have taken and are taking place in the movement. -

Broadcast December 23 at 7 Pm & December 25 at 1 Pm on WOWT Channel 6

Broadcast December 23 at 7 pm & December 25 at 1 pm on WOWT Channel 6 Ernest Richardson, principal pops conductor Parker Esse, stage director/choreographer Maria Turnage, associate stage director ROBERT H. STORZ FOUNDATION PROGRAM The Most Wonderful Time of the Year/ Jingle Bells JAMES LORD PIERPONT/ARR. ELLIOTT Christmas Waltz VARIOUS/ARR. KESSLER Happy Holiday - The Holiday Season IRVING BERLIN/ARR. WHITFIELD Joy to the World TRADITIONAL/ARR. RICHARDSON Mother Ginger (La mère Gigogne et Danse russe Trepak from Suite No. 1, les polichinelles) from Nutcracker PIOTR ILYICH TCHAIKOVSKY from Nutcracker PIOTR ILYICH TCHAIKOVSKY We Are the Very Model of a God Bless Us Everyone from Modern Christmas Shopping Pair A Christmas Carol from Pirates of Penzance ALAN SILVESTRI/ARR. ROSS ARTHUR SULLIVAN/LYRICS BY RICHARDSON Silent Night My Favorite Things from FRANZ GRUBER/ARR. RICHARDSON The Sound of Music RICHARD RODGERS/ARR. WHITFIELD Snow/Jingle Bells IRVING BERLIN/ARR. BARKER O Holy Night ADOLPH-CHARLES ADAM/ARR. RICHARDSON Let It Snow, Let It Snow, Let It Snow JULE STYNE/ARR. SEBESKY We Need a Little Christmas JERRY HERMAN/ARR. WENDEL Frosty the Snowman WALTER ROLLINS/ARR. KATSAROS Hark All Ye Shepherds TRADITIONAL/ARR. RICHARDSON Sleigh Ride LEROY ANDERSON 2 ARTISTIC DIRECTION Ernest Richardson, principal pops conductor and resident conductor of the Omaha Symphony, is the artistic leader of the orchestra’s annual Christmas Celebration production and internationally performed “Only in Omaha” productions, and he leads the successful Symphony Pops, Symphony Rocks, and Movies Series. Since 1993, he has led in the development of the Omaha Symphony’s innovative education and community engagement programs. -

Theological Reflections on the Charismatic Movement – Part 1 Churchman 94/1 1980

Theological Reflections on the Charismatic Movement – Part 1 Churchman 94/1 1980 J. I. Packer I My subject is a complex and still developing phenomenon which over the past twenty years has significantly touched the entire world church, Roman Catholic, Orthodox, Anglican and non-episcopal Protestant, at all levels of life and personnel and across a wide theological spectrum.1 Sometimes it is called Neo-Pentecostalism because, like the older Pentecostalism which ‘spread like wildfire over the whole world’2 at the start of this century, it affirms Spirit-baptism as a distinct post-conversion, post-water-baptism experience, universally needed and universally available to those who seek it. The movement has grown, however, independently of the Pentecostal denominations, whose suspicions of its non-separatist inclusiveness have been—and in some quarters remain—deep, and its own preferred name for itself today is ‘charismatic renewal’.3 For it sees itself as a revitalizing re-entry into a long-lost world of gifts and ministries of the Holy Spirit, a re-entry which immeasurably deepens individual spiritual lives, and through which all Christendom may in due course find quickening. Charismatic folk everywhere stand on tiptoe, as it were, in excited expectation of great things in store for the church as the movement increasingly takes hold. Already its spokesmen claim for it major ecumenical significance. ‘This movement is the most unifying in Christendom today’, writes Michael Harper; ‘only in this movement are all streams uniting, and all ministries -

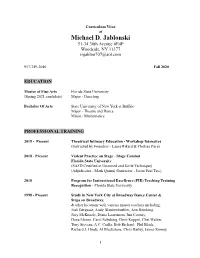

Michael Jablonski's CV

Curriculum Vitae of Michael D. Jablonski 51-34 30th Avenue #E4P Woodside, NY 11377 [email protected] 917-749-2040 Fall 2020 EDUCATION Master of Fine Arts Florida State University (Spring 2021 candidate) Major - Directing Bachelor Of Arts State University of New York at Buffalo Major - Theatre and Dance Minor - Mathematics PROFESSIONAL TRAINING 2019 - Present Theatrical Intimacy Education - Workshop Intensives (Instructed by Founders - Laura Rikard & Chelsea Pace) 2018 - Present Violent Practice on Stage - Stage Combat Florida State University (SAFD Certified in Unarmed and Knife Technique) (Adjudicator - Mark Quinn) (Instructor - Jason Paul Tate) 2018 Program for Instructional Excellence (PIE) Teaching Training Recognition - Florida State University 1998 - Present Study in New York City at Broadway Dance Center & Steps on Broadway, & other locations with various master teachers including: Josh Bergasse, Andy Blankenbuehler, Ann Reinking, Joey McKneely, Diana Laurenson, Jim Cooney, Dana Moore, Carol Schuberg, Dorit Koppel, Chet Walker, Tony Stevens, A.C. Ciulla, Bob Richard, Phil Black, Richard J. Hinds, Al Blackstone, Chris Bailey, James Kinney 1 2010 - Present One on One Studio - New York City On Camera Workshops (Selection by Audition) Instructors - Bob Krakower & Marci Phillips EMPLOYMENT HISTORY 2020 - 2021 Fall & Spring Florida State University, Florida Instructor In The School of Theatre (Intro to Music Theatre Dance - New Course Developed) (Instructor of Record - Michael D. Jablonski) (Culminations - Senior Seminar Course) (Instructor - Michael D. Jablonski) 2019 - 2020 Fall & Spring Florida State University, Florida Instructor In The School of Theatre (Intro to Music Theatre Dance - New Course Developed) (Instructor of Record - Michael D. Jablonski) Graduate Teaching Assistant (Performance I - Uta Hagen Acting Class) (Instructor of Record - Chari Arespacochaga) (Performance I Lab - Uta Hagen Workshop class) (Instructor of Record - Michael D.