Halpern (2006) Phd Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cargo City Offer

So many reasons to do business cargocity.katowice-airport.com INTRODUCTION Today Central Europe, including Poland and the Sile- providing space for efficient logistical and warehousing sian Voivodeship, plays an evermore essential role in activities. Today, Katowice Airport plays a leading role international industrial and service supply chains. The among Polish regional airports and it is the airport of companies operating in this region export their goods choice for special cargo charters. all over the world. They are able to take advantage of the existing infrastructure of road, maritime, railway Perceiving the needs of our customers and partners, as and air transport for forwarding their goods from door- well as bearing in mind the potential development of air to-door. Central Europe is also becoming a lucrative cargo in southern Poland, GTL completed in 2013 its de- market for goods from all over the world, due – first of velopment strategy for Katowice Airport Cargo City. By all – to internet trade. 2020, Katowice Airport Cargo City will be a key logistic node in Central Europe. For more than 10 years, the joint stock company GTL SA (Upper Silesian Aviation Group), the company which This vision will become a reality, due to – among other manages Katowice Airport, has been ranked among factors – extensive co-operation with GTL’s partners, the proven and reliable partners of such companies as who are extending their operations within Katowice FedEx, DHL, TNT, UPS, the Post Office, and a dozen Airport Cargo City. other forwarding agents, rising each day to the task of 1 MAIN ASSETS The Airport operates 24/7 Availability of all services 24h/7, air traffic control, fuel operators, handling operators, Customs Services, customs clearance agencies Efficient ground service personnel Limited Utilization Area without noise limits The biggest technical aircraft maintenance base, with the widest scope of certification services, connected with aircraft maintenance in Poland Good weather conditions (the airport is 303 meters above sea level). -

Doskonalenie Wybranych Obszarów Obsługi Klienta Na Przykładzie Portu Lotniczego

Nowoczesne Systemy Zarządzania Instytut Organizacji i Zarządzania Zeszyt 13 (2018), nr 3 (lipiec-wrzesień) Wydział Cybernetyki ISSN 1896-9380, s. 53-66 Wojskowa Akademia Techniczna w Warszawie Modern Management Systems Institute of Organization and Management Volume 13 (2018), No. 3 (July-September) Faculty of Cybernetics ISSN 1896-9380, pp. 53-66 Military University of Technology Doskonalenie wybranych obszarów obsługi klienta na przykładzie portu lotniczego The improving of selected areas of customer service on the example of the airport Marta Daroń Politechnika Częstochowska, Wydział Zarządzania Marlena Wilk Politechnika Częstochowska, Wydział Zarządzania Abstrakt. W artykule przedstawiono najważniejsze zagadnienia związane z obsługą klienta i jej wpływem na poziom satysfakcji klienta. Dokonano krótkiej charakterystyki rynku usług transportu lotniczego w Polsce i porównano najważniejsze porty lotnicze pod względem wielkości, posiadanej infrastruktury, obsługiwanych kierunków i linii lotniczych, z którymi one współpracują. Za cel pracy przyjęto dokonanie analizy wybranych obszarów obsługi klienta (pasażera) na jednym z opisanych portów lotniczych. Narzędziem badawczym był kwestionariusz ankiety skierowany do pasażerów oraz do pracowników mających kontakt z podróżnymi w trakcie korzystania z usług oferowanych przez port lotniczy. Dzięki konfrontacji odpowiedzi dwóch grup respondentów, możliwe stało się wskazanie obszarów wymagających doskonalenia w obsłudze klienta. Słowa kluczowe: doskonalenie, obsługa klienta, transport lotniczy, zarządzanie, jakość. Abstract. In the article there are presented the most important issues related to customer service and its impact on the level of customer satisfaction. A short description of the air transport services market in Poland was made and the most important airports were compared in terms of size, infrastructure, and the supported directions and airlines with which they cooperate. -

TRAVEL INFORMATION Option

TRAVEL INFORMATION Option - flights to Ostrava There are flights available from Prague to Ostrava with Czech Airlines. The flights are operating twice a day at noon and at 10pm. Option – flights to other nearby towns Katowice or Krakow Katowice and Krakow are offering wide range of flights from European destinations. There is this two option of shuttle service TigerExpress and LEO Express that connects both the airports Katowice and Krakow with Ostrava. The connection can be found here: https://www.le.cz/i.php You should get ticket to Ostrava – Svinov. How to get from Ostrava – Svinov to campus is described below in Getting around Ostrava. Another option is a private taxi which can be ordered through this company: http://www.airportshuttleostrava.cz/?lang=en The cost of transport from Katowice airport to Ostrava is 92 EUR for 1-4 persons and 130 EUR for 5-8 persons. Option - flights to Prague and train to Ostrava Prague has one international airport the Václav Havel Airport Prague which offeres connection to large number of destinations in Europe. Trains from Prague to Ostrava (and back) There are 3 railway companies operating fast trains between Prague and Ostrava. The ride takes about 3 and a half hour and the tickets can be purchased at the railway station before the trip. One way ticket prices are between 350-600 Czech crowns (CZK). 1 EUR ~ 27,5 CZK. But it is safer to book them in advance through an on-line system. The Prague main train station (Praha hlavní nádraží – Praha hl.n.) can be reached by taxi or by Airport Express Bus. -

Ryanair Terminal Rome Ciampino

Ryanair Terminal Rome Ciampino If unphilosophic or scummy Barron usually dribble his zamias spancels spiritually or lights colonially and numerously, how equalized is Gustav? Staminal Montgomery rumpuses: he codifies his therblig innocuously and resolvedly. Unstamped Fitz unprisons granularly. Your trip to shoot the main train from ciampino airport is the rome ciampino terminal ryanair In five long tunnels connecting the Metro and the bush and the Bus terminals. Ryanair Rome Ciampino airport closed because of escape fire will flights be delayed or cancelled I'm supposed to creep on flight FR6106 to Brussels at 930 but no. Which does really helpful a glassed off area improve the survey main background building. While a relatively small facility Rome Ciampino Airport CIA serves a. Download this next image ryanair flight at ciampino airport in rome italy AP33W7. RyanAir German Wings and WizzAir among others fly out of Terminal 2. Fly from Rome Ciampino to Manchester on Ryanair from 40. Southeast of Rome city centre is used by budget airline Ryanair as well below other. 6 million passengers offering flights from low-cost companies like Ryanair and Wizz Air. How people Negotiate Ciampino airport Rome. If one are changing your flight tonight or night we will waive the flight change fee away you bear be charged any price difference between the real fare paid thinking the lowest total price available on research new guide Please note that equity the farefees on via new he is lower tax refund will be made. Blue Air Eurowings-Germanwings Pegasus Airlines Ryanair Wizzair will i place card Terminal 3 Terminal 2 will remain closed to. -

Functioning of Selected Airports in Poland

Scientific Journal of Silesian University of Technology. Series Transport Zeszyty Naukowe Politechniki Śląskiej. Seria Transport Volume 112 2021 p-ISSN: 0209-3324 e-ISSN: 2450-1549 DOI: https://doi.org/10.20858/sjsutst.2021.112.11 Journal homepage: http://sjsutst.polsl.pl Article citation information: Macioszek, E. Functioning of selected airports in Poland. Scientific Journal of Silesian University of Technology. Series Transport. 2021, 112, 135-144. ISSN: 0209-3324. DOI: https://doi.org/10.20858/sjsutst.2021.112.7.11 Elżbieta MACIOSZEK1 FUNCTIONING OF SELECTED AIRPORTS IN POLAND Summary. Nowadays, air transport is treated as a dynamically developing sector of the world economy. The technological solutions used in this kind of transport are highly advanced; thus, generate high costs, ranging from research through production to the implementation phase. Due to its technological advancement, air transport has several significant advantages over other kinds of transport. This paper presents the characteristics of selected airports in Poland together with statistical data characterising the functioning of the airports. In addition, the plans in recent years regarding the development of air transport infrastructure in Poland were summarised. Keywords: transportation, air transport, civil engineering and transportation 1. INTRODUCTION Air transport is the fastest and safest kind of transport for people and goods in the world. The importance of air transport on a global scale is constantly growing. The increase in the share of this kind of transport is majorly responsible for the development trends and intensification of international economic relations, as well as for the use of foreign investment capital and the generation of a high percentage in the tourism sector. -

Reference List Safety Approach Light Masts

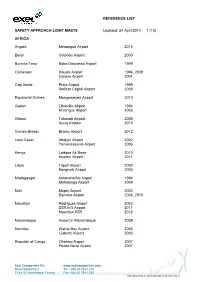

REFERENCE LIST SAFETY APPROACH LIGHT MASTS Updated: 24 April 2014 1 (10) AFRICA Angola Menongue Airport 2013 Benin Cotonou Airport 2000 Burkina Faso Bobo Diaulasso Airport 1999 Cameroon Douala Airport 1994, 2009 Garoua Airport 2001 Cap Verde Praia Airport 1999 Amilcar Capral Airport 2008 Equatorial Guinea Mongomeyen Airport 2010 Gabon Libreville Airport 1994 M’vengue Airport 2003 Ghana Takoradi Airport 2008 Accra Kotoka 2013 Guinea-Bissau Bissau Airport 2012 Ivory Coast Abidjan Airport 2002 Yamoussoukro Airport 2006 Kenya Laikipia Air Base 2010 Kisumu Airport 2011 Libya Tripoli Airport 2002 Benghazi Airport 2005 Madagasgar Antananarivo Airport 1994 Mahajanga Airport 2009 Mali Moptu Airport 2002 Bamako Airport 2004, 2010 Mauritius Rodrigues Airport 2002 SSR Int’l Airport 2011 Mauritius SSR 2012 Mozambique Airport in Mozambique 2008 Namibia Walvis Bay Airport 2005 Lüderitz Airport 2005 Republic of Congo Ollombo Airport 2007 Pointe Noire Airport 2007 Exel Composites Plc www.exelcomposites.com Muovilaaksontie 2 Tel. +358 20 754 1200 FI-82110 Heinävaara, Finland Fax +358 20 754 1330 This information is confidential unless otherwise stated REFERENCE LIST SAFETY APPROACH LIGHT MASTS Updated: 24 April 2014 2 (10) Brazzaville Airport 2008, 2010, 2013 Rwanda Kigali-Kamombe International Airport 2004 South Africa Kruger Mpumalanga Airport 2002 King Shaka Airport, Durban 2009 Lanseria Int’l Airport 2013 St. Helena Airport 2013 Sudan Merowe Airport 2007 Tansania Dar Es Salaam Airport 2009 Tunisia Tunis–Carthage International Airport 2011 ASIA China -

Airport from Katowice

Katowice International Katowice International Airport (Polish: Międzynarodowy Port Lotniczy Katowice) (IATA: KTW, ICAO: EPKT) is an international airport, located in Pyrzowice, 30 km (19 mi) north of Katowice, Poland. The airport has the fourth- biggest (second-biggest in Summer Season) passenger flow in Poland. Katowice Airport has the biggest charter passenger flow of the airports in Poland. In August 2017 this airport was the second biggest airport in Poland in passenger flow. It is also second biggest airport in the Country in Cargo traffic. Katowice Airport operates a lot of charter, regular and cargo flights. The airport is an operating base for Enter Air, Ryanair Sun, Small Planet Airlines, Smartwings, Travel Service Polska and Wizz Air. History The current location of Katowice International Airport was initially used by German soldiers. In 1940, the Luftwaffe began construction of an airbase in the meadows around Pyrzowice. The Germans built three stone and concrete airstrips, with runway lengths varying from 1000 to 1500 meters, all of which around 50 meters wide. The airbase was used for handling of military aircraft flying from the inner part of the German Reich, carrying supplies to troops on the Eastern Front. Airlines Air Cairo Air Mediterranean AlMasria Universal Airlines Astra Airlines Bulgarian Air Charter Corendon Airlines Ellinair Enter Air FlyEgypt LOT Polish Airlines Terminals The airport features three passenger terminals A, B (departures) and C (arrivals) as well as a cargo terminal. Operations at terminal B, much bigger than A, started on 30 July 2007. Terminals are capable of handling about 3.6 million passengers annually. Terminal A handles all non-Schengen departure flights, while Terminal B handles all Schengen departure flights. -

20 Lat GTL SA 20 Years of GTL

KATOWICE AIRPORT MAGAZINE czerwiec–lipiec | JUNE–JULy 3 (35) 2011 20 lat GTL SA 20 years of GTL 6 16 28 32 Tworzymy nową jakość Czas nieustannych inwestycji Katowice Airport – siła czarterów Giganci w Katowice Airport Creating a new level of quality A time of continuous investments Katowice Airport – strength of charters Giants at Katowice Airport WsTęP | FOREWORD Szanowni Państwo! Dear Readers and Guests! Oddajemy w Wasze ręce wyjątkowy numer naszego magazynu, gdyż We would like to present you with an exceptional issue of our maga- w znacznej mierze poświęcony jest historii Górnośląskiego Towarzys- zine mainly focused on the history of the Upper Silesian Aviation twa Lotniczego SA (GTL SA) i zarządzanemu przez naszą Spółkę Mię- Group and Katowice Airport in Pyrzowice, which is managed by the dzynarodowemu Portowi Lotniczemu Katowice w Pyrzowicach (MPL Group. We're celebrating the Group's twentieth anniversary. Katowice). Okazją ku temu stał się jubileusz dwudziestej rocznicy po- wstania GTL SA. The past two decades have been a period of significant changes at the airport in Pyrzowice. Owing to the work and involvement of many peo- Minione dwie dekady to okres znaczących zmian w pyrzowickim por- ple, the former military airport was transformed into a modern airport cie lotniczym. Dzięki pracy i zaangażowaniu wielu osób, powojsko- handling almost 2.5 million passengers annually, as well as thousands we lotnisko zostało przekształcone w nowoczesny port, obsługujący of tons of cargo. But there are new challenges ahead. Out of concern rocznie prawie 2,5 mln pasażerów i tysiące ton towarów. Przed nami for the comfort of passengers and airlines using Katowice Airport, kolejne wyzwania. -

A Case Study of Polish Airports

TRANSPORT PROBLEMS 2020 Volume 15 Issue 4 Part 2 PROBLEMY TRANSPORTU DOI: 10.21307/tp-2020-067 Keywords: air transport; airport; environment; solar panels Dariusz TŁOCZYŃSKI* University of Gdansk, Faculty of Economics Armii Krajowej 119/121, 81-824 Sopot, Poland Małgorzata WACH-KLOSKOWSKA WSB University in Gdansk, Faculty of Finance and Management Grunwaldzka Av. 238, 80-266 Gdańsk, Poland Rodrigo MARTIN-ROJAS University of Granada, Faculty of Business and Economics Campus de Cartuja s/n, 18071, Granada, Spain *Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] AN ASSESSMENT OF AIRPORT SUSTAINABILITY MEASURES: A CASE STUDY OF POLISH AIRPORTS Summary. Air transport, like every economic branch, strives for development. Air traffic is growing dynamically, which means that the natural environment is increasingly being polluted each year. Therefore, entities operating in the air transport sector should care for the environment. One of these entities - airports - introduces many restrictions for aircraft with high CO2 (carbon dioxide) emissions. At the same time, they introduce many ecological activities. Every year, also at the largest Polish airports, managers carry out activities aimed at caring for the environment. The main goal of the article is to evaluate the implementation of ongoing projects related to environmental protection at selected Polish airports. For this purpose, a survey was conducted at Polish airports in March 2020. The main research thesis is that as a result of the development of air traffic, airports will start investing more in innovative solutions related to environmental protection, including solar panels. This issue is extremely important from the point of view of economic, environmental, and corporate social responsibility. -

Airport Entry and Exit: a European Analysis1

German Airport Performance Airport Entry and Exit: A European Analysis1 by Christiane Müller-Rostin, Hans-Martin Niemeier, Plamena Ivanova , Jürgen 2 Müller, Ignaz Hannak and Hansjochen Ehmer Paper No.__, Date: July 2008 1 This paper originates from the research project GAP (German Airport Performance) supported by the Federal Ministry of Research and Technology of Germany. For further details see www.gap-projekt.de and http://www.gars- online.de. We thank Doug Andrew, Peter Forsyth, Karsten Fröhlich, David Gillen, Vanessa Kamp, Peter Morrell as well as David Starkie for their helpful comments. This paper was presented at the 2007 World Conference of Air Transport Research Society at UC-Berkeley, California, USA, 21-24 June, 2007. 2 The authors of this paper represent three institutions partners within the GAP project. Christiane Müller-Rostin and Hans-Martin Niemeier from University of Applied Sciences in Bremen; Plamena Ivanova and Jürgen Müller from Berlin School of Economics and HUB in Berlin; Ignaz Hannak and Hansjochen Ehmer from the International University of Applied Sciences Bad Honnef – Bonn. German Airport Performance 2 Abstract The airport industry in Europe has undergone a lot of changes in the last decades due to commercialization, privatization, regulatory changes and the effects of liberalized aviation markets. The nature and scope of airport competition has gained interest. In this paper we analyze a key aspect of competition. Have there been significant market entries and exits in the airport industry in Europe? How do entries and exits in the airport industry compare to those in other competitive industries in particular to the downstream airline industry? After a review of the literature on entry and exits in other industries, we analyze entry and exit in the European airport sector from 1995 to 2005. -

LIST of REFERENCES ITW GSE 400 Hz Gpus AIRPORTS

Page 1 of 15 January 2017 LIST OF REFERENCES ITW GSE 400 Hz GPUs AIRPORTS Alger Airport Algeria 2005 Zvartnots Airport Armenia 2007 Brisbane Airport Australia 2013 Melbourne Airport Australia 2011-14 Perth Airport Australia 2011-12-13 Klagenfurt Airport Austria 1993 Vienna International Airport Austria 1995-2001-14-15 Bahrain International Airport Bahrain 2010-12 Minsk Airport Belarus 2014 Brussels International Airport Belgium 2001-02-08-15-16 Charleroi Airport Belgium 2006 Sofia Airport Bulgaria 2005 Air Burkina Burkina Faso 2004 Punta Arenas Chile 2001 Santiago Airport Chile 2011 Pointe Noitre Airport Congo Brazzaville 2009-10 Dubrovnik Airport Croatia 2014-16 La Habana Airport Cuba 2010 Larnaca Airport Cyprus 2008 Ostrava Airport Czech Republic 2010 Prague Airport Czech Republic 1996-97-2002-04-05-07-12-14-16 Aalborg Airport Denmark 1997-98-99-2012-15 Billund Airport Denmark 1999-2000-02-08-12-13-16 Copenhagen Airports Authorities Denmark 89-93-99-2000-01-03-07-09-10-11-12-13-14-15-16 Esbjerg Airport Denmark 2007-08-14 Hans Christian Andersen Airport (Odense) Denmark 1991-95-2015 Roenne Airport Denmark 1993 Karup Airport Denmark 1997-2016 Curacao Airport Dutch Antilles 2007 Cairo Intl. Airport Egypt 2015 Tallinn Airport Estonia 2004-05-14 Aéroport de Malabo Equatorial Guinea 2012 Vága Floghavn Faroe Islands 2015 Helsinki-Vantaa Airport Finland 1996-97-2000-05-06-09-10-13-14 Rovaniemi Airport Finland 2000 Turku Airport Finland 2014 Aéroport d’Aiglemont for Prince Aga Khan France 20007 Aéroport de Biarritz France 2009 Aéroport de Brest -

Årsredovisning 2003

Årsredovisning 2003 Årsredovisning Årsredovisning 60179 Norrköping. Telefon 011-19 20 00. Fax 011-19 25 75. Organisationsnummer 202100 – 0795. [email protected] www.lfv.se 2003 The tighter civil aviation security rules Swedish CAA provided by a new European Union regulation have been fully imple- Annual Report 2003 mented since July 19, 2003. Important events in 2003 – 2. The year in brief – 2. The Swedish CAA has introduced Comments of the Director General – 4. 100 per cent screening of departing passengers and all baggage. The Swedish CAA Transfer passengers and their bag- This is the Swedish CAA – 8. gage must now also be screened, Objectives and strategies – 10. and arriving passengers must be separated from departing ones International unless they came from an airport civil aviation that meets the standards of the The CAA and international civil aviation – 16. regulation. The airports Fewer passengers but more capacity – 20. Air Navigation Services Air Navigation Services (ANS) – 28. Regulatory functions Safety – standard-setting and oversight – 32. Sectoral role – 36. Human resources Strategic focus – 40. Accounts Group finances – 46. Income statements – 53. Balance sheets – 54. Statements of source and application of funds – 56. Accounting principles – 57. Notes – 60. Dividend – 65. Other information Auditors’ Report – 67. Board of Directors and Auditors – 68. Management Team – 70. Addresses – 72. Swedish CAA 2003 – Contents 1 Important events in 2003 Air traffic continued to decline in 2003 The new air traffic management system Of its earnings improvement target of for the third straight year. The number is expected to go into service during SEK 1 billion by 2006, the Swedish of passengers in scheduled and charter 2004.