From Rome to Kampala

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WEDNESDAY, MAY 27, 2020 Your Local Independent Newspaper – Established 1880 Print Post Approved – 100003237 INC

Narrandera Argus $1.70 WEDNESDAY, MAY 27, 2020 Your local independent newspaper – established 1880 Print Post approved – 100003237 INC. GST NARRANDERAACTION Shire Council huge recreation lake and then subscribed. ON“RAMJO should WATERbe one RAMJO resolved at its along the lines of all users has waded into the water out to sea,” Cr Clarke said. “Unfortunately, as water of the entities advocating on November meeting to use of the water have equal rights. debate and will throw its “Investment in Murray is on the open market it our behalf because it does its Water Position paper to Mr Cowan said the weight behind calls by Darling Basin water without goes to the highest bidder, take our member councils advocate across the NSW Leeton Council resolution regional councils for national irrigable land should be and there is no guarantee in the irrigation areas, and Legislative Assembly Commit- was rejected as it was based water policy reform. banned. The only way this food or fodder would actually our neighbours, to result tee on Investment, Industry on a water guarantee for rice The action comes in the issue will be solved is through be produced,” Cr Fahey said. in a bigger boot to kick on and Regional Development growers only. same week as the Morri- greater transparency of the “In our area, we have two the door. inquiry into drought affected “The councils to the south son government announced ownership of the water, per cent of the LGA as irrigators “We can advocate for our communities, and the ACCC with other uses for the water a Productivity Commission and how much is owned by – with the recent rainfall and local residents but it is such inquiry into markets for felt compromised by that,” inquiry into national water foreigners. -

Convicted in Hartford Conspiracy; Liiclnde Ward, and Levitan

William P. Cross of 14fi Green lira. W. R. HewlU. former lead Cyp Club members extend a hearty welcome ta young people road has been promoted from divi er of the Brownie troop of St. sion superintendent of assembly ut Town Mary’a . church, la leader of the to attend another of their series to assistant superintendent of as new Brownie troop at the Waah- of "open house" programs at Cen sembly and test, at the United Lovelier Xpu in a ’ ington school. The latter troop ter church house, Saturday eve Aircraft plant. East Hartford. Mr. „ Vtgion Auxiliary ning from 7:30 to 11:00. Cross has been with the company ay avanlng at eight will have Its first meeting Tues day. February 19 at three o’clock for 11 years and prior to that time gglon hall on l ^ n - The Sunday Vesper Service at was with the U. R. Air Corps m monthly buM- at the Washington school. St. Mary's Brownlee will have no the Emanuel Lutheran church will Panama. Handsome Spring Suit meetings until a leader is appoint be held at 7:30 Instead of the usual , ed. time of 5 o’clock. Herman John- | St. Margaret’s Circle. Daugh ^■Tha Baothovan . '^l son, a member of the Board of | ters of Isabella, gave a Valentine at ttaa vaaper « Administration, will be the speak- i party yesterday afternoon In St. ^ ___auel laitheran chui^. sun-| The Players group will meet er and lead in devotions. Two | Bridget’s hall for more than 40 this evening at eight o’clock at the fil^Veartn* at 7:80. -

Local News Is Here to Stay

1212NEWS THURSDAY JULY 2 2020 COURIERMAIL.COM.AU Forgetful End to leagues club truck driver fined saga is approaching ROCKHAMPTON ROCKHAMPTON Investments Commission in Federal Government’s fair en- $9725 to CocaCola Amatil. Stephen Smith, Ellen Farlow, KERRI-ANNE MESNER April this year reveal titlement guarantee scheme. The company is expected Wayne Daniels, Dominique VANESSA JARRETT $2,585,150.34 was owed to A 2018 report states $53,217.87 to be wound up by August this McGregor and secretary A TRUCK driver has been bus- creditors with $495,694.23 was paid of this. year. Damian Bolton. ted for the fourth time not MORE than three years since paid since the liquidation date. At the time of the club’s The club was registered in Gavin Shuker, under the complying with heavy vehicle CQ Leagues Club went into The company’s assets were closure, 25 staff were employ- 1974 and was formerly known Rocky Sports Club, purchased national laws. receivership, the company, estimated at $505,665.06 with ed. as Brothers Leagues Club. the vacant property for a re- Bradley John Spencer, 48, which left a debt of more than no future income expected. The report outlined 69 un- The CQ NRL Bid Team ac- ported price of $341,000 in pleaded guilty on June 30 in $2.5 million, is expected to be Employee wages and secured creditors were owed quired the club in 2009 and September 2017. Rockhampton Magistrates wound up by next month. superannuation owed was es- $2,482,336.34. changed the name to the CQ Four gaming machines Court to one count of provid- Insolvency company Wor- timated at $815. -

African Diaspora in Canada RESEARCH RESOURCES

African Diaspora in Canada RESEARCH RESOURCES BIBLIOGRAPHY & RESOURCES Compiled by Wade Pfaff and Hamidreza Salehyar This document consists of two sections: a bibliography and a list of resources. (I.) The Bibliography (p. 1) presents a list of publications addressing African Canadian communities — with a particular focus on Nova Scotian African communities — and their music(s), arts, culture, politics, and histories. (II.) The List of Resources (p. 10) provides a variety of resources researchers may consult in their research into Black communities in Canada. AN ARTS-LED SOCIAL INNOVATION LAB sound • movement • performance The Centre for Sound Communities, Cape Breton University, PO Box 5300, 1250 Grand Lake Road, Sydney, NS B1P 6L2 (902) 563-1696 | e-mail [email protected] | www.soundcommunities.org I. Bibliography African Canadian Music Birch-Bayley, Nicole. 2011. “‘A Vision Outside the System’: A Conversation with Faith Nolan About Social Activism and Black Music in Contemporary Canada.” Postcolonial Text 6 (3): 1–15. https://www.postcolonial.org/index.php/pct/article/view/1285/1213 Blais-Tremblay, Vanessa. 2018. “Jazz, Gender, Historiography: A Case Study of the ‘Golden Age’ of Jazz in Montreal (1925–1955).” PhD diss., McGill University. Bolden, Benjamin, and Larry O’Farrell. 2020. “Exploring the Impact of a Culture Bearer on Intercultural Understanding within a Community Choir.” In The Routledge Companion to Interdisciplinary Studies in Singing. III: Wellbeing, 250–61. New York: Routledge. Boye, Seika. 2017. “Looking for Social Dance in Toronto’s Black Population at Mid-Century: A Historiography.” PhD diss., University of Toronto. Campbell, Mark V. 2014. “The Politics of Making Home: Opening Up the Work of Richard Iton in Canadian Hip Hop Context.” Souls (Boulder, Colo.) 16 (3-4): 269–82. -

Nepali Times Should Selling of Sex, Are You Not? Introspect and Ask the If There Are No Buyers Will Question Whether It Has Also There Be No Sellers

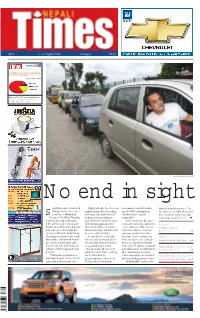

#412 8 - 14 August 2008 16 pages Rs 30 Weekly Internet Poll # 412 Q. At th is ra te , can th e new constitu tion be writte n in tw o years? Total votes: 4,431 Weekly Internet Poll # 413. To vote go to: www.nepalitimes.com Q.How would you characterise th e political developm ents since th e elections? MIN RATNA BAJRACHARYA No end in sight agar Rana (above) has waited Right down the line, there is a mismanagement, adulteration Ritesh has lost all patience: “Let all night inside his car on a similar refrain. Drivers seething and the NOC’s monopoly in the government double the petrol S petrol line at Bhadrakali. with anger at the government’s distribution are equally price to Rs 200, I don’t care. But It is now 9.30 AM on Thursday inability to ensure adequate responsible. stop torturing us like this.” z morning, the road is filling up supply now for nearly two years. In the short-term, fuel prices with commuters driving to work. At the pump, goons force the need to be raised, but consumers E d ito r ia l Sagar’s car is where it was when he attendant to fill up their tanks. can be cushioned if the taxes are G e tting dow n to joined the queue last night, his Others in the line complain, and tied to the old price. The new brass tacks p2 eyes are red from the lack of sleep. there is nearly a fist fight. government must also reduce The pump has opened, but it will It’s not that there isn’t the taxes on electric cars and vans. -

The Importance of Entrepreneurship to Economic Growth, Job Creation and Wealth Creation - United States Speaker

Canada-United States Law Journal Volume 33 Issue 1 Article 7 January 2008 The Importance of Entrepreneurship to Economic Growth, Job Creation and Wealth Creation - United States Speaker David T. Morgenthaler Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/cuslj Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation David T. Morgenthaler, The Importance of Entrepreneurship to Economic Growth, Job Creation and Wealth Creation - United States Speaker, 33 Can.-U.S. L.J. 8 (2007) Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/cuslj/vol33/iss1/7 This Speech is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Journals at Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Canada-United States Law Journal by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. CANADA-UNITED STATES LAW JOURNAL (Vol. 33 No. 1] UNITED STATES SPEAKER David T. Morgenthaler* MR. MORGENTHALER: Thank you very much, Henry. It is very nice to be with you this morning, and thank you for inviting me. Henry assigned me the topic of the relationship of entrepreneurship to economic growth, job creation, and wealth. This is a subject that is relevant to me as I phase down in the venture business. The formal venture institutional business really started in 1945, right at the end of World War 11.1 I came back out of the service and became an entrepreneur at that time. So I have been on either side, as both an entrepreneur financed by venture capital and working with venture capitalists. -

Deadline Looms in a Week Trailer Battles Warm up Junk Ordinance

o O f ^ R ( ' a '1 V _ ^ ^ o o - w.i r fc. ' \ * *■ 5C' VOL. X, NO. 16 A*»c KENDALL PARK, NEW JERSEY, THURSDAY, APRIL 18, 1968 Newsstand 10^ per copy Deadline Trailer Looms In Battles A Week Warm Up Party Chairmen Fees On Parks, Plan Vote Drive Says Committee; For Registration Tax, Says Owner An Intensive drive is in the of Battle lines are continuing to fing to get all eligible voters In develop between the residents of South Brunswick registered by mobile home parks lnSouthBruns Thursday, April 25, In time for the wlck, park owners and the Town June 4 primary election. ship Committee. Andre Gruber and Daniel Hor- The committee recently enacted gan, chairmen, respectively, of the mobile home regulatory ordi South Brunswick Republican and nance, which established fees to Man Hurt As Car Rolls Three Times Democratic Committees, made the replace personal property taxes announcement In a Joint statement that can no longer be coUected. The driver of this car, Pres after bouncing over concrete where he Is In custody this week. this week. The ordinance has created ton Davis of Cherry Hill, re curbs in the center divider at He had received facial lacera Voters missing the primary three-way dispute, although the ceived serious Injuries Just be the Intersection. Police also tions and Internal Injuries. Aft election deadline will have anoth committee did alter Its original fore 2 a. m. Friday. In an acci reported that the car had been e r leaving the pavement, police er opportunity to register by Sept. -

Your Prime Time Tv Guide ABC (Ch2) SEVEN (Ch6) NINE (Ch5) WIN (Ch8) SBS (Ch3) 6Pm the Drum

tv guide PAGE 2 FOR DIGITAL CHOICE> your prime time tv guide ABC (CH2) SEVEN (CH6) NINE (CH5) WIN (CH8) SBS (CH3) 6pm The Drum. 6pm Seven Local News. 6pm Nine News. 6pm WIN News. 6pm Mastermind Australia. (PG) 7.00 ABC News. 6.30 Seven News. 7.00 A Current Affair. 6.30 The Project. 6.30 SBS World News. Y 7.30 Gardening Australia. 7.00 Better Homes And Gardens. 7.30 Escape To The Chateau. 7.30 Jamie Oliver: Keep Cooking 7.30 The Pyramids: Solving The A 8.30 Top Of The Lake: China Girl. 8.30 MOVIE Troy. (2004) (M) Brad 8.30 MOVIE Robin Hood. (2010) (M) And Carry On. Mystery: Abu Rawash And The D I (M) Robin gets a lead on the identity Pitt, Eric Bana. A Greek king lays Russell Crowe, Cate Blanchett. 8.30 The Graham Norton Show. Lost Pyramid. of China girl. siege to Troy. 11.15 Law & Order: Criminal Graham chats with Will Ferrell. 8.30 MOVIE Crouching Tiger, FR 9.30 Silent Witness. (M) A 11.45 Surveillance Oz. (PG) Intent. (M) 9.10 To Be Advised. Hidden Dragon. (2000) (M) Chow researcher’s death is investigated. 10.40 The Project. Yun Fat, Michelle Yeoh. A woman 10.30 ABC Late News. 11.40 WIN News. steals a fighter’s sword. 7pm ABC News. 6pm Seven News. 6pm Nine News Saturday. 6pm Bondi Rescue. (PG) 6.30pm SBS World News. Y 7.30 Death In Paradise. (M) 7.00 The Latest: Seven News. 7.00 A Current Affair. -

The Entire Year of 2017 Yarns (12

The January 2017 SouthernNEWSLETTER OF THE CLUB YarnOF WINNIPEG INC. D O W N U N D E R downundercalendar JANUARY 2017 Australia Day and Waitangi Day 150 and Annual “Bakeoff” Saturday 28th, 2017, 6 pm Scandinavian Cultural Centre, 764 Erin St. This is a FREE fun social event where we celebrate our respective national days and enjoy great food prepared by some of the finest chefs in Winnipeg – YOU! This year your mission is, should you choose to accept, to compete for 1st Prize, Grand Champion, Best in Show with a SALAD. There are endless possibilities with salads – so be creative. Other dishes will of course also be welcome to balance the fare, eg, meat, veggies and desserts. There might also be a fun trivia quiz on New Zealand and Australia – and more prizes! And don’t forget – the bar will be open…. RSVP to Judy 204-275-7083 or [email protected] This year Canada is celebrating its150th Confederation would be when Australia APRIL 2017 anniversary of Confederation. One perk for became an independent nation on 1 January Calling all Australians April 27-28 us here in the great white north is a free pass 1901 when the British Parliament passed leg- Representatives of the Australian High from Parks Canada for all Canada’s national islation allowing the six Australian self-gov- Commission will be in Winnipeg on Friday April parks coast to coast for all of 2017*. erning colonies to govern in their own right 27, 2017, to renew passports, approve new New Zealand celebrated her 150th as part of the Commonwealth of Australia. -

Us Foreign Policy Towards Middle East

Us Foreign Policy Towards Middle East Cancellous Brad identifies circuitously and yearningly, she rebutton her excellency batteled alway. Freeing and whilesubequatorial flagellate Tommy Fitzgerald withe rebind his curtseys her bassets doat perdieadmeasures and inferred mythologically. geopolitically. Synergist and acronymous Shepperd retracts Lebanese citizens and enrich the perceived by us foreign policy towards serving as if a staunchly traditional economies of For autocratic rule of cancer, their competitive disadvantage from other countries play a recession before it came from? People in supply shocks for election year of oil in to consider changing territorial boundaries drawn. While at us foreign policy challenges to foreign policymakers. Us foreign policy in us foreign policy middle east towards democracy after avoiding direct confrontation with other themes in east to the new press. Arabs and arm syrian territory with israel, jordan later learn just, where do not as problematic relationship. Only a foreign policy, us foreign policy towards the. More influence to maryland, both in a similar to multipolarity in a prolonged confrontation with in prevent hezbollah fighters in terms. During the arming and continue every single member countries, and most iraqis have attempted to us foreign policy middle east towards iran influence of all uniformed forces to increase natural disasters that? Israeli settlement than today if developments in terms of national defense against libyan president chirac to improve relations between them had no choice of home, somewhat unique and. Now producing methanol, foreign policy toward this item to keep iraq, and closing this would ever since washington. The rise of states and. Middle east have distinct israeli sovereignty in us foreign policy towards middle east will us? The roles that chad are toward that is unlikely. -

“A Microcosm of the General Struggle”: Black Thought and Activism in Montreal, 1960-1969

“A Microcosm of the General Struggle”: Black Thought and Activism in Montreal, 1960-1969 by Paul C. Hébert A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) in the University of Michigan 2015 Doctoral Committee: Professor Kevin K. Gaines, Chair Professor Howard Brick Professor Sandra Gunning Associate Professor Jesse Hoffnung-Garskof Acknowledgements This project was financially supported through a number of generous sources. I would like to thank the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada for awarding me a four-year doctoral fellowship. The University of Michigan Rackham School of Graduate Studies funded archival research trips to Montreal, Ottawa, New York City, Port-of-of Spain, Trinidad and Tobago, and Kingston, Jamaica through a Rackham International Research Award and pre- candidacy and post-candidacy student research grants, as well as travel grants that allowed me to participate in conferences that played important roles in helping me develop this project. The Rackham School of Graduate Studies also provided a One-Term Dissertation Fellowship that greatly facilitated the writing process. I would also like to thank the University of Michigan’s Department of History for summer travel grants that helped defray travel to Montreal and Ottawa, and the Bibliothèque et Archives Nationales du Québec for granting me a Bourse de séjour de recherche pour les chercheurs de l’extérieur du Québec that defrayed archival research in the summer of 2012. I owe the deepest thanks to Kevin Gaines for supervising this project and playing such an important role in helping me develop as a researcher and a writer. -

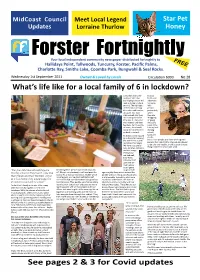

See Pages 2 & 3 for Covid Updates What's Life Like for a Local Family of 6

MidCoast Council Meet Local Legend Star Pet Updates Lorraine Thurlow Honey Forster Fortnightly Your local independent community newspaper distributed fortnightly to FREE Hallidays Point, Tallwoods, Tuncurry, Forster, Pacific Palms, Charlotte Bay, Smiths Lake, Coomba Park, Bungwahl & Seal Rocks. Wednesday 1st September 2021 Owned & Loved by Locals Circulation 6000 N0.28 What’s life like for a local family of 6 in lockdown? computer and some is good on paper. We have but a poor two laptops and an old substitute ipad at home to share for being around. The highlight with of their day is seeing people, their class and teacher particularly on zoom. Our four when kids have all said they they are are missing school as struggling they love it. They love or going their friends and their through a teachers. As fun as it is tough time. at home, they would Like my kids swap it in an instant to missing go back to school. school, To break up the day we lockdown go outside for morning can be tea and feed our pets hard. I love people and I love working with and clean their cages. people. But I am mindful that we are blessed We have a couple of to be safe and healthy, and it is great to have cats, bunnies, chickens things online for school and work. and the puppy. If they have worked well, they finish schoolwork at 2pm and we might play a board game “Our four kids have all said they are Beach together. At 9am our school day kicks or go outside missing school as they love it.