NICARAGUA Transcript of Bertha Inés Cabr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Life and Films of the Last Great European Director

Macnab-05480001 macn5480001_fm May 8, 2009 9:23 INGMAR BERGMAN Macnab-05480001 macn5480001_fm May 19, 2009 11:55 Geoffrey Macnab writes on film for the Guardian, the Independent and Screen International. He is the author of The Making of Taxi Driver (2006), Key Moments in Cinema (2001), Searching for Stars: Stardom and Screenwriting in British Cinema (2000), and J. Arthur Rank and the British Film Industry (1993). Macnab-05480001 macn5480001_fm May 8, 2009 9:23 INGMAR BERGMAN The Life and Films of the Last Great European Director Geoffrey Macnab Macnab-05480001 macn5480001_fm May 8, 2009 9:23 Sheila Whitaker: Advisory Editor Published in 2009 by I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd 6 Salem Road, London W2 4BU 175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010 www.ibtauris.com Distributed in the United States and Canada Exclusively by Palgrave Macmillan 175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010 Copyright © 2009 Geoffrey Macnab The right of Geoffrey Macnab to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or any part thereof, may not be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. ISBN: 978 1 84885 046 0 A full CIP record for this book is available from the British Library A full CIP record is available from the Library of Congress Library of Congress -

28Th Leeds International Film Festival Presents Leeds Free Cinema Week Experience Cinema in New Ways for Free at Liff 28 from 7 - 13 November

LIFF28th 28 Leeds International Film Festival CONGRATULATIONS TO THE LEEDS INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL IN YOUR 28TH YEAR The BFI is proud to partner with Screen Yorkshire in a fantastic year for filmmaking in the region INCLUDING ‘71 GET SANTA SCREENING AT LIFF28 X + Y CATCH ME DADDY & LIFF28 OPENING NIGHT FILM TESTAMENT OF YOUTH Image: (2014) Testament of Youth James Kent Dir. bfi.org.uk/FilmFund Film Fund Ad LIFF 210x260 2014-10_FINAL 3.indd 1 27/10/2014 11:06 WELCOME From its beginnings at the wonderful, century-old Hyde Park Leeds International Film Festival is a celebration of both Picture House to its status now as a major national film event, film culture and Leeds itself, with this year more than 250 CONGRATULATIONS Leeds International Film Festival has always aimed to bring screenings, events and exhibitions hosted in 16 unique a unique and outstanding selection of global film culture locations across the city. Our venues for LIFF28 include the TO THE LEEDS INTERNATIONAL to the city for everyone to experience. This achievement main hub of Leeds Town Hall, the historic cinemas Hyde is not possible without collaborations and this year we’ve Park Picture House and Cottage Road, other city landmarks FILM FESTIVAL IN YOUR 28TH YEAR assembled our largest ever line-up of partners. From our like City Varieties, The Tetley, Left Bank, and Royal Armouries, long-term major funders the European Union and the British Vue Cinemas at The Light and the Everyman Leeds, in their Film Institute to exciting new additions among our supporting recently-completed Screen 4, and Chapel FM, the new arts The BFI is proud to partner with Screen Yorkshire organisations, including Game Republic, Infiniti, and Trinity centre for East Leeds. -

Philosophical Themes in the Films of Ingmar Bergman Et Al

Philosophical Themes in the Films of Ingmar Bergman et al Fall 2017 Honors 362-01 MWF 11-11:50am; DH 146 Prerequisite: acceptance into the University Honors Program, or consent of instructor. 3 credits. Also counts for 7AI, 7SI, 7VI. Instructor: Charles Webel, Ph.D. Delp-Wikinson Chair and Professor, Peace Studies. Roosevelt Hall 253. email: [email protected] Office Hours: Mon/Wed/Fr 1:00-2:20pm, & by appointment Catalog Description The films of Ingmar Bergman offer a range of jumping-off points for some traditional debates in philosophy in areas such as the philosophy of religion, ethics, and value theory more broadly. Bergman’s oeuvre also offers an entry point for a critical examination of existentialism. This course will investigate some of the philosophical questions posed and positions raised in these films within an auteurist framework. We will also examine the legitimacy of the auteurist framework for film criticism and the representational capacity of film for presenting philosophical arguments. Course Learning Outcomes Upon completion of this course, students will have: a. Understood a range of philosophical positions within the tradition of Western philosophy in general and the intellectual movement called “existentialism” in particular. b. Engaged in a critical analysis of Bergman’s relationship to existentialism, based on synthesizing individual arguments and positions presented throughout his oeuvre. c. Engaged in critical analyses of various philosophical themes, traditions, and problematics, especially ethics, epistemology, philosophical psychology, and political philosophy. d. Understood arguments for and against the capacity of film to present philosophical arguments, focusing on the films of Ingmar Bergman, as well as selected films by other great directors. -

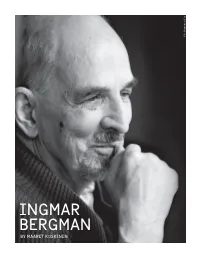

Ingmar Bergman by Maaret-Koskinen English.Pdf

Foto: Bengt Wanselius Foto: INGMAR BERGMAN BY MAARET KOSKINEN Ingmar Bergman by Maaret Koskinen It is now, in the year of 2018, almost twenty years ago that Ingmar Bergman asked me to “take a look at his hellofamess” in his private library at his residence on Fårö, the small island in the Baltic Sea where he shot many of his films from the 1960s on, and where he lived until his death in 2007, at the age of 89. S IT turned out, this question, thrown foremost filmmaker of all time, but is generally re Aout seemingly spontaneously, was highly garded as one of the foremost figures in the entire premeditated on Bergman’s part. I soon came to history of the cinematic arts. In fact, Bergman is understand that his aim was to secure his legacy for among a relatively small, exclusive group of film the future, saving it from being sold off to the highest makers – a Fellini, an Antonioni, a Tarkovsky – whose paying individual or institution abroad. Thankfully, family names rarely need to be accompanied by a Bergman’s question eventually resulted in Bergman given name: “Bergman” is a concept, a kind of “brand donating his archive in its entirety, which in 2007 name” in itself. was added to the UNESCO World Heritage List, and the subsequent formation of the Ingmar Bergman Bergman’s career as a cinematic artist is unique in Foundation (www.ingmarbergman.se). its sheer volume. From his directing debut in Crisis (1946) to Fanny and Alexander (1982), he found time The year of 2018 is also the commemoration of to direct more than 40 films, including some – for Bergman’s birth year of 1918. -

Ingmar Bergman Roland Pöntinen

INGMAR BERGMAN MUSIC FROM THE FILMS ROLAND PÖNTINEN piano BIS-2377 STENHAMMAR QUARTET | TORLEIF THEDÉEN cello Ingmar Bergman – Music From the Films 1 J.S. Bach: Sarabande from Cello Suite No.5 in C minor, BWV1011 3'47 Viskningar och rop & Saraband [Cries and Whispers & Saraband] 2 Robert Schumann: Aufschwung from Fantasiestücke, Op.12 3'17 Musik i mörker & Sommarnattens leende [Music in Darkness & Smiles of a Summer Night] 3 Frédéric Chopin: Nocturne in C sharp minor, Op.27 No.1 5'04 Fanny och Alexander [Fanny and Alexander] 4 Frédéric Chopin: Prelude in D minor, Op.28 No.24 2'36 Musik i mörker 5 J.S. Bach: Sarabande from Cello Suite No.4 in E flat major, BWV1010 5'02 Höstsonaten [Autumn Sonata] 6 W.A. Mozart: Fantasy in C minor, K 475 12'26 Ansikte mot ansikte [Face to Face] 7 Frédéric Chopin: Mazurka in A minor, Op.17 No.4 3'43 Viskningar och rop 8 Franz Schubert: Andante sostenuto 9'37 Second movement of Sonata in B flat major, D 960 Larmar och gör sig till [In the Presence of a Clown] 2 9 Domenico Scarlatti: Sonata in D major, K 535 3'11 Djävulens öga [The Devil’s Eye] 10 Frédéric Chopin: Prelude in A minor, Op.28 No.2 2'17 Höstsonaten 11 Domenico Scarlatti: Sonata in E major, K 380 4'18 Djävulens öga 12 J.S. Bach: Variation 25 from Goldberg Variations, BWV988 6'39 Tystnaden [The Silence] 13 J.S. Bach: Sarabande from Cello Suite No.2 in D minor, BWV1008 5'43 Såsom i en spegel [Through a Glass Darkly] 14 Robert Schumann: In modo d’una marcia 8'44 Second movement of Piano Quintet in E flat major, Op.44 Fanny och Alexander TT: 78'28 Roland Pöntinen piano Stenhammar Quartet [Schumann: Piano Quintet] Peter Olofsson & Per Öman violins · Tony Bauer viola · Mats Olofsson cello Torleif Thedéen cello [Bach: Sarabandes] 3 Tystnaden (1963) Gunnel Lindblom and Jörgen Lindström as Anna and her son Johan © 1963 AB Svensk Filmindustri. -

Retrospektive (PDF)

61. Internationale Filmfestspiele Berlin Retrospektive Ingmar Bergman Ansikte mot ansikte (Von Angesicht zu Angesicht/Face to Face) von Ingmar Bergman mit Liv Ullmann, Erland Josephson, Aino Taube, Schweden 1975/76, schwedisch mit deutsch/französischen Untertiteln, Kopie: Cinémathèque suisse, Lausanne Ansiktet (Das Gesicht/The Magician) von Ingmar Bergman mit Max von Sydow, Ingrid Thulin, Gunnar Björnstrand, Schweden 1958, schwedisch mit englischen elektronischen Untertiteln, Kopie: Swedish Film Institute, Stockholm Aus dem Leben der Marionetten (Aus dem Leben der Marionetten/From the Life of the Marionettes) von Ingmar Bergman mit Christine Buchegger, Robert Atzorn, Martin Benrath, Rita Russek, BRD 1979/80, deutsch mit englischen Untertiteln, Kopie: Swedish Institute, Stockholm Beröringen / The Touch von Ingmar Bergman mit Elliott Gould, Bibi Andersson, Max von Sydow, Schweden/USA 1970/71, englisch/schwedisch mit englischen Untertiteln, Kopie: Swedish Film Institute, Stockholm Bilder från lekstugan (Images from the Playground) von Stig Björkman mit Ingmar Bergman, Harriet Andersson, Bibi Andersson, Schweden 2009, schwedisch mit englischen Untertiteln, Digibeta: Swedish Film Institute, Stockholm Bris Reklamfilmer von Ingmar Bergman mit Bibi Andersson, Barbro Larsson, John Botvid, Schweden 1951-53, schwedisch mit englischen Untertiteln, Kopie: Swedish Institute, Stockholm Daniel (Episode aus Stimulantia) von Ingmar Bergman mit Ingmar Bergman, Käbi Laretei, Daniel Sebastian Bergman, Schweden 1964–67, schwedisch mit englischen Untertiteln, -

Auteur and the Film Text in Audience Experiences : Ingmar Bergman – a Case Study

SCENES FROM AN AUDIENCE THE AUTEUR AND THE FILM TEXT IN AUDIENCE EXPERIENCES : INGMAR BERGMAN – A CASE STUDY 1 For my family, may we continue to inspire each other. 2 List of figures and tables Table 1: social statistics on divorce from scb.be - p. 19 Table 2: number of participants in Sweden according to gender and date of birth - p. 76 Table 3: number of participants in Belgium and Sweden according to gender and date of birth - p. 76 3 Table of Contents List of figures and tables 3 Table of Contents 4 Acknowledgments 8 Abstract English 9 Summary Dutch 10 Summary Swedish 12 one Introduction 14 1. Goals 15 2. Why Bergman? Spatial and temporal motivations. 20 3. Chapter breakdown 21 two Theory 24 1. New cinema history studies 24 1.1. The audience in focus 24 1.2. Janet Staiger 26 1.3. Annette Kuhn 28 1.3.1. Cinema memory 29 1.3.2. Memory and identity 31 1.3.3. Identity and the cinema 33 1.3.4. Memories and emotions 34 2. Traces of texts and authors in new cinema history studies 38 2.1. Exhibition, space, and place 39 2.2. Programming, admissions, and economic analysis 41 2.3. Distribution and circulation 43 2.4. Audience Reception studies 44 2.4.1. Texts 44 4 2.4.2. The auteur coming up 48 3. Revisiting auteur theory 49 4. Bergman-studies 53 4.1.1. Overview 54 4.1.2. Bergman-studies in Belgium 55 4.1.3. Reception studies on Ingmar Bergman 58 5. -

Housewife, Who Are All These Women Around Me

If This Is a “Real” Housewife, Who Are All These Women Around Me?: An Examination of The Real Housewives of Atlanta and the Persistence of Historically Stereotypical Images of Black Women in Popular Reality Television. Dominique Bunai Thesis submitted to the faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science In Sociology Ellington T. Graves, Co-Chair Anthony K. Harrison, Co-Chair Rachelle Brunn-Bevel March 19, 2014 Blacksburg, VA Keywords: black women; stereotypes; reality TV; Real Housewives If This Is a “Real” Housewife, Who Are All These Women Around Me?: An Examination of The Real Housewives of Atlanta and the Persistence of Historically Stereotypical Images of Black Women in Popular Reality Television. Dominique Bunai ABSTRACT Stereotypical images of blacks have persisted throughout multiple forms of media for decades, with one of the most recent arenas being reality television programming. This study examines the Bravo Television network series The Real Housewives of Atlanta to consider the impact of reality television on the image of black women in America today. This increasingly popular show is the most viewed in The Real Housewives franchise, and demonstrates that black women in America do not embody any one historical or contemporary stereotype of black women in particular, but rather are a compilation of these stereotypes depending on the situation at hand. iii DEDICATION This is for all the women who taught me how women are supposed to act, because life will always be a stage. Corinne and Jessica Maginsky, Dawn Best, Alethea “Swanie” Morris, Cheryl Toussaint, Lorna Forde, all my Atoms sisters, my partner in crime Niree Martin, her mother Rhonda and sister Nefia, my rock Elizabeth Reyes, my sister Catherine Clark, my sweetheart grandmother Alma Harris, my godmother Shirley Mitchell, and last but never least, my tireless mother Geraldine Bunai. -

UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Passionate Failures: The Diva Onscreen Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2117p747 Author McElroy, Dolores C Publication Date 2019 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Passionate Failures: The Diva Onscreen By Dolores C McElroy A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Media in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Linda Williams, Chair Professor Mary Ann Doane Professor James Q. Davies Summer 2019 © 2019 Dolores C McElroy All Rights Reserved Abstract Passionate Failures: The Diva Onscreen By Dolores C McElroy Doctor of Philosophy in Film & Media University of California, Berkeley Professor Linda Williams, Chair I place the origins of the diva in the 19th century artistic movement l’art pour l’art (“art for art’s sake”) in order to show that the diva was born of mechanization and the reaction against it. Therefore, to consider the diva “onscreen” is to acknowledge the very dialectic that birthed this paradoxical prima donna: uniqueness vs. reproduction, private vs. public, ritual vs. politics. I understand the notion of the female voice as a way to anchor the meaning of “diva,” which has come to be used too promiscuously, sometimes denoting just about anyone whose manner of self-presentation puts them on some imagined scale between self-confidence and vanity. I do not aim to offer a strict definition of the term, but I do aim to draw from certain tropes of the presentation of the diva onscreen the contours of particular relations of desire that hem the specificity of what “diva” might mean. -

New Releases New Releases

November December Summer Interlude Raiders of the Lost Ark -S M T W T F S S M T W T F S New Releases New Releases 6:30pm The Seventh Seal 1:00pm 1:00pm Burning Shoplifters Opens Nov 2 The Magician INGMAR BERGMAN Kristin Lavransdatter Wings INGMAR BERGMAN LIV ULLMANN Opens Dec 21 with Live Piano Burning Science Fair 8:45pm 4:45pm Mirai Accompaniment THE GREAT WAR Opens Nov 2 The War at Home Science Fair The Silence Opens Dec 21 SPECIAL SCREENINGS INGMAR BERGMAN 4:45pm Transit 6:30pm For more New Release Opens Nov 9 7:00pm Winter Light Winter Light titles visit tiff.net INGMAR BERGMAN The Wild Pear Tree INGMAR BERGMAN The Sacrifice SPECIAL SCREENINGS 7:00pm Opens Nov 23 8:30pm Thirst Girl The Nun INGMAR BERGMAN SPECIAL SCREENINGS Opens Nov 23 9:00pm Happy as Lazzaro Peeping Tom Opens Nov 30 SPECIAL SCREENINGS 1 For more New Release 10:30am 6:30pm 6:15pm 6:30pm 11:00am 1:00pm titles visit tiff.net Secret Movie Club What the Complete From the Life of Night is My Future Lawrence of Arabia The Big Parade 1 2 3 Image Could Be: Works the Marionettes INGMAR BERGMAN THE GREAT WAR with Live Piano 1:00pm INGMAR BERGMAN 10:30am 6:00pm 6:15pm 6:30pm Transit 1:00pm by Faraz Anoushahpour, 9:00pm 3:45pm Accompaniment Daisy Kenyon Parastoo Anoushahpour, THE GREAT WAR Secret Movie Club Sofie All These Women Summer Interlude Possessed JOAN CRAWFORD 9:00pm Black Mother Peeping Tom 3:00pm LIV ULLMANN INGMAR BERGMAN INGMAR BERGMAN JOAN CRAWFORD and Ryan Ferko Strange Machines: with Khalik Allah SPECIAL SCREENINGS 3:45pm 1:00pm 3:15pm WAVELENGTHS 8:35pm 9:00pm -

A Gift from Janus Films

3? he Museum of Modern Art FOR RELEASE: Thursday, August 3* 1967 I 153 street, New York, N.Y. 10019 Tel. 245-3200 Cable: Modernart j; • to yj -/ i 27 FILM CUSSICS: A GIFT FROM JANUS FILMS I An unparalleled gift of twenty-seven foreign film classics has been given to the I Film Archive of The Museum of Modern Art by Saul J. Turell and William Becker, I President and Chairman of the Board of Janus Frllms, Inc., Uillard Van Dyke, Director I of the Museum's Department of Film, announced today. Included in the generous I bequest are twenty-one outstanding works directed by Bryan Forbes, Satyajit Ray, I Juan Bardem, Andrzej Wajda, Alf Sjl5berg, Ermanno Olmi and Ingmar Bergman which will I be screened at the Museum from August 5 through September 10. (program attached) I In making their gift to the Museum "as a token of our admiration for the I superb service which the Museum's film department, almost alone in the United I States, has performed in attempting to preserve for the future outstanding examples I of this newest of art forms," Mr. Turell and 14r. Becker commented: "In our own I production experience, working frequently with classic motion pictures, we have I found that a number of wonderful films have already completely disappeared. In I other cases, only poor or incomplete copies remain. To people who love films, it is I a saddening thing to realize that the reactions and emotions which these films I evoked will never be experienced again. We know that the Museum's efforts will I help put an end to this destruction." I In making the gift Mr. -

Janus Films [email protected] • 212-756-8761 Press Contact

Booking Inquiries: Janus Films Press Contact: Courtney Ott [email protected] • 212-756-8761 [email protected] • 646-230-6847 “I never need to concern myself about present opinion or the judgment of posterity. I am a name that has not been recorded anywhere and that will disappear when I myself disappear; but a little part of me will live on in the triumphant masterwork of the anonymous craftsmen. A dragon, a devil, or perhaps a saint—it does not matter which.” —Ingmar Bergman INGMAR BERGMAN’S CINEMA No name is more synonymous with the postwar explosion of international art-house cinema than Ingmar Bergman, a master storyteller who startled the world with his stark intensity and naked pursuit of the most profound metaphysical and spiritual questions. In a career that spanned six decades, Bergman directed dozens of films in an astonishing array of tones, ranging from comedies whose lightness and complexity belie their brooding hearts to groundbreaking formal experiments and excruciatingly intimate explorations of family relationships. Text by Peter Cowie BIOGRAPHY EARLY LIFE AND PATH drew directly from his own early years.) what one British drama critic called “a TO THE THEATER Ingmar also enjoyed the family’s summer bloodshot, brooding nightmare.” holidays in the province of Dalarna, Ingmar Bergman was born on July 14, 1918, where his father had when young helped A CAREER IN THE CINEMA during the final year of the Great War, to construct the local railway. Here he which also saw the population of Europe could indulge his daydreaming, a habit In 1942, following the premiere of his play ravaged by the Spanish flu, and Sweden he retained throughout his adult life.