Islam and the Formation of the Modern

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

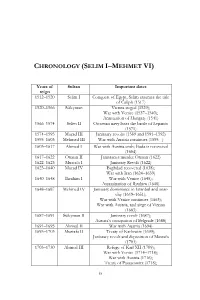

Selim I–Mehmet Vi)

CHRONOLOGY (SELIM I–MEHMET VI) Years of Sultan Important dates reign 1512–1520 Selim I Conquest of Egypt, Selim assumes the title of Caliph (1517) 1520–1566 Süleyman Vienna sieged (1529); War with Venice (1537–1540); Annexation of Hungary (1541) 1566–1574 Selim II Ottoman navy loses the battle of Lepanto (1571) 1574–1595 Murad III Janissary revolts (1589 and 1591–1592) 1595–1603 Mehmed III War with Austria continues (1595– ) 1603–1617 Ahmed I War with Austria ends; Buda is recovered (1604) 1617–1622 Osman II Janissaries murder Osman (1622) 1622–1623 Mustafa I Janissary Revolt (1622) 1623–1640 Murad IV Baghdad recovered (1638); War with Iran (1624–1639) 1640–1648 İbrahim I War with Venice (1645); Assassination of İbrahim (1648) 1648–1687 Mehmed IV Janissary dominance in Istanbul and anar- chy (1649–1651); War with Venice continues (1663); War with Austria, and siege of Vienna (1683) 1687–1691 Süleyman II Janissary revolt (1687); Austria’s occupation of Belgrade (1688) 1691–1695 Ahmed II War with Austria (1694) 1695–1703 Mustafa II Treaty of Karlowitz (1699); Janissary revolt and deposition of Mustafa (1703) 1703–1730 Ahmed III Refuge of Karl XII (1709); War with Venice (1714–1718); War with Austria (1716); Treaty of Passarowitz (1718); ix x REFORMING OTTOMAN GOVERNANCE Tulip Era (1718–1730) 1730–1754 Mahmud I War with Russia and Austria (1736–1759) 1754–1774 Mustafa III War with Russia (1768); Russian Fleet in the Aegean (1770); Inva- sion of the Crimea (1771) 1774–1789 Abdülhamid I Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca (1774); War with Russia (1787) -

Rituals of Islamic Spirituality: a Study of Majlis Dhikr Groups

Rituals of Islamic Spirituality A STUDY OF MAJLIS DHIKR GROUPS IN EAST JAVA Rituals of Islamic Spirituality A STUDY OF MAJLIS DHIKR GROUPS IN EAST JAVA Arif Zamhari THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY E P R E S S E P R E S S Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at: http://epress.anu.edu.au/islamic_citation.html National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Zamhari, Arif. Title: Rituals of Islamic spirituality: a study of Majlis Dhikr groups in East Java / Arif Zamhari. ISBN: 9781921666247 (pbk) 9781921666254 (pdf) Series: Islam in Southeast Asia. Notes: Includes bibliographical references. Subjects: Islam--Rituals. Islam Doctrines. Islamic sects--Indonesia--Jawa Timur. Sufism--Indonesia--Jawa Timur. Dewey Number: 297.359598 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU E Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2010 ANU E Press Islam in Southeast Asia Series Theses at The Australian National University are assessed by external examiners and students are expected to take into account the advice of their examiners before they submit to the University Library the final versions of their theses. For this series, this final version of the thesis has been used as the basis for publication, taking into account other changesthat the author may have decided to undertake. -

A History of Ottoman Poetry

; All round a thousand nightingales and many an hundred lay. ' Come, let us turn us to the Court of Allah: Still may wax The glory of the Empire of the King triumphant aye, 2 So long as Time doth for the radiant sun-taper at dawn A silver candle-stick upon th' horizon edge display, ^ Safe from the blast of doom may still the sheltering skirt of Him Who holds the world protect the taper of thy life, we pray. Glory the comrade, Fortune, the cup-bearer at thy feast; * The beaker-sphere, the goblet steel-enwrought, of gold inlay ! I give next a translation of the famous Elegy on Sultan Suleyman. It is, as usual, in the terkib-bend form. There is one other stanza, the last of all, which I have not given. It is a panegyric on Suleyman's son and successor Selim II, such as it was incumbent on Baqi, in his capacity of court poet, to introduce into a poem intended for the sovereign but it strikes a false note, and is out of harmony with, and altogether unworthy of, the rest of the poem. The first stanza is addressed to the reader. Elegy on Sultan Sulcym;in. [214] thou, fool-tangled in the incsli of fame and glory's snare! How long this lusl of things of 'I'linc lliat ceaseless lluwolli o'er? Hold tliou in mitiil thai day vvliicli shall be hist of life's fair spring, When Mii:<ls the I uli|)-tinlcd cheek to auluniu-lcaf must wear, » Wiieii lliy lasl (Iwclling-placc must Ije, e'en like tlie dregs', tlic diisl, « When mi<l ihe iiowl of cheer must fail the stone I'injc's haml doth licar. -

Understanding the Concept of Islamic Sufism

Journal of Education & Social Policy Vol. 1 No. 1; June 2014 Understanding the Concept of Islamic Sufism Shahida Bilqies Research Scholar, Shah-i-Hamadan Institute of Islamic Studies University of Kashmir, Srinagar-190006 Jammu and Kashmir, India. Sufism, being the marrow of the bone or the inner dimension of the Islamic revelation, is the means par excellence whereby Tawhid is achieved. All Muslims believe in Unity as expressed in the most Universal sense possible by the Shahadah, la ilaha ill’Allah. The Sufi has realized the mysteries of Tawhid, who knows what this assertion means. It is only he who sees God everywhere.1 Sufism can also be explained from the perspective of the three basic religious attitudes mentioned in the Qur’an. These are the attitudes of Islam, Iman and Ihsan.There is a Hadith of the Prophet (saw) which describes the three attitudes separately as components of Din (religion), while several other traditions in the Kitab-ul-Iman of Sahih Bukhari discuss Islam and Iman as distinct attitudes varying in religious significance. These are also mentioned as having various degrees of intensity and varieties in themselves. The attitude of Islam, which has given its name to the Islamic religion, means Submission to the Will of Allah. This is the minimum qualification for being a Muslim. Technically, it implies an acceptance, even if only formal, of the teachings contained in the Qur’an and the Traditions of the Prophet (saw). Iman is a more advanced stage in the field of religion than Islam. It designates a further penetration into the heart of religion and a firm faith in its teachings. -

The Islamic Traditions of Cirebon

the islamic traditions of cirebon Ibadat and adat among javanese muslims A. G. Muhaimin Department of Anthropology Division of Society and Environment Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies July 1995 Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] Web: http://epress.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Muhaimin, Abdul Ghoffir. The Islamic traditions of Cirebon : ibadat and adat among Javanese muslims. Bibliography. ISBN 1 920942 30 0 (pbk.) ISBN 1 920942 31 9 (online) 1. Islam - Indonesia - Cirebon - Rituals. 2. Muslims - Indonesia - Cirebon. 3. Rites and ceremonies - Indonesia - Cirebon. I. Title. 297.5095982 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design by Teresa Prowse Printed by University Printing Services, ANU This edition © 2006 ANU E Press the islamic traditions of cirebon Ibadat and adat among javanese muslims Islam in Southeast Asia Series Theses at The Australian National University are assessed by external examiners and students are expected to take into account the advice of their examiners before they submit to the University Library the final versions of their theses. For this series, this final version of the thesis has been used as the basis for publication, taking into account other changes that the author may have decided to undertake. In some cases, a few minor editorial revisions have made to the work. The acknowledgements in each of these publications provide information on the supervisors of the thesis and those who contributed to its development. -

Qisas Contribution to the Theory of Ghaybah in Twelver Shı

− QisasAA Contribution to the Theory of Ghaybah in Twelver Shı‘ism QisasAA Contribution to the Theory of Ghaybah in Twelver Shı‘ism− Kyoko YOSHIDA* In this paper, I analyze the role of qisasAA (narrative stories) materials, which are often incorporated into the Twelver Shı‘ite− theological discussions, by focusing mainly on the stories of the al-KhidrA (or al- Khadir)A legend in the tenth and the eleventh century ghaybah discussions. The goal is to demonstrate the essential function that the narrative elements have performed in argumentations of the Twelver Shı‘ite− theory of Imam. The importance of qisasAA materials in promulgating the doctrine of Imamah− in the Twelver Shı‘ism− tended to be underestimated in the previous studies because of the mythical and legendary representations of qisasAA materials. My analysis makes clear that qisasAA materials do not only illustrate events in the sacred history, but also open possibilities for the miraculous affairs to happen in the actual world. In this sense, qisasAA materials have been utilized as a useful element for the doctrinal argumentations in the Twelver Shı‘ism.− − Keywords: stories, al-Khidr,A occultation, Ibn Babawayh, longevity Introduction In this paper, I analyze how qisasAA traditions have been utilized in the promulgation of Twelver Shı‘ite− doctrine. The term qisasAA (sing. qissah AA ) means narrative stories addressed in the Qur’an− principally. However, it also includes the orated and elaborated tales and legends based on storytelling that flourished in the early Umayyad era (Norris 1983, 247). Their contents vary: archaic traditions spread in the pre-Islamic Arab world, patriarchal stories from Biblical and Jewish sources, and Islamized sayings and maxims of the sages and the ascetics of the day.1 In spite of a variety of the different sources and origins, Muslim faith has accepted these stories as long as they could support and advocate the Qur’anic− *Specially Appointed Researcher of Global COE Program “Development and Systematization of Death and Life Studies,” University of Tokyo Vol. -

Spiritual Surrender: from Companionship to Hierarchy in the History of Bektashism Albert Doja

Spiritual surrender: from companionship to hierarchy in the history of Bektashism Albert Doja To cite this version: Albert Doja. Spiritual surrender: from companionship to hierarchy in the history of Bek- tashism. Numen: International Review for the History of Religions, 2006, 53 (4), pp.448-510. 10.1163/156852706778941996. halshs-00405963 HAL Id: halshs-00405963 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00405963 Submitted on 21 Jul 2009 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. NUMEN 53,4_f3_448-510II 10/30/06 10:27 AM Page 448 Author manuscript, published in "Numen: International Review for the History of Religions 53, 4 (2006) 448–510" Numen: International Review for the History DOI of Religions, : 10.1163/156852706778941996 vol. 53, 2006, n° 4, pp 448–510 SPIRITUAL SURRENDER: FROM COMPANIONSHIP TO HIERARCHY IN THE HISTORY OF BEKTASHISM ALBERT DOJA Summary The system of beliefs and practices related to Bektashism seems to have cor- responded to a kind of liberation theology, whereas the structure of Bektashi groups corresponded more or less to the type of religious organization conven- tionally known as charismatic groups. It becomes understandable therefore that their spiritual tendency could at times connect with and meet social, cultural and national perspectives. -

ANG TARIQA AY NAGTUTURO NG MAGANDANG ASAL Assalamu Alaykum Wa Rahmatullahi Wa Barakatuh

ANG TARIQA AY NAGTUTURO NG MAGANDANG ASAL Assalamu Alaykum wa Rahmatullahi wa Barakatuh. Authu Billahi Minash-shaytanir Rajeem, Bismillahir Rahmanir Raheem. Madad Ya Rasulallah, Madad Ya As’habi Rasulallah, Madad Ya Mashayikhina, Shaykh Abdullah Daghestani, Shaykh Nazim al-Haqqani. Dastur. Abu Ayyub al-Ansari. Madad. Tariqatunas sohba, wal khayru fil jam’iyya. Ang pagiging marespeto sa awliya, sa mga Ulama at sa mga magulang ang tinuturo sa Tariqa. “At-Tariqatu kulluha adab.”Ang tariqa ay binubuo ng magandang asal.Walang magandang asal kung walang tariqa. Karamihan sa mga muslim ngayon ay wala ng magandang asal. Maganda ang pagiging masunurin at magandang asal sa mga mgaulang pero ngayon wala ng kagandahang asal dahil di na sila sumusunod sa tariqa.Ang tariqa ay nagututuro ng kagandahang asal. Dito sa Anatoia, ang mga tariqa ay pinagbawala. Nung mawala ang Ottomans napuno na ng demonyo ang lugar na ito. Ang Tariqa ay pinagbawal din sa ilang muslim na bansa. Mayroon din na ibang bansa ang masama ang tingin sa tariqa. Sabi nila kapag nagpakita ka ng magandang asal at respeto ay masama ka daw. Ganito ang pagkagalit nila sa Tariqa. Sinusundan nila ang shaytan. Akala nila na dasal at pag-ayuno lang ang kailangan sa Islam. Mahalaga ang matutuo ng kagandahan asal. Tinuruan ng magandang asal ang Banal Propeta Muhammad alayhis salatu was salam at kanya naman ito naituro sa mga Sahaba. Ang mga Sahaba naman ang nagturo sa mga Ulama at Awliya. Ito ang daan niya. May mga zawiyas na ipinasara na dahil nawala na ang mga Shaykhs at Ulama. Ang mga natira na lang ay mga masasamang loob.May ilan din ang mga sumusunod sa kanila at nadadala sa kasamaan. -

1 the Turks and Europe by Gaston Gaillard London: Thomas Murby & Co

THE TURKS AND EUROPE BY GASTON GAILLARD LONDON: THOMAS MURBY & CO. 1 FLEET LANE, E.C. 1921 1 vi CONTENTS PAGES VI. THE TREATY WITH TURKEY: Mustafa Kemal’s Protest—Protests of Ahmed Riza and Galib Kemaly— Protest of the Indian Caliphate Delegation—Survey of the Treaty—The Turkish Press and the Treaty—Jafar Tayar at Adrianople—Operations of the Government Forces against the Nationalists—French Armistice in Cilicia—Mustafa Kemal’s Operations—Greek Operations in Asia Minor— The Ottoman Delegation’s Observations at the Peace Conference—The Allies’ Answer—Greek Operations in Thrace—The Ottoman Government decides to sign the Treaty—Italo-Greek Incident, and Protests of Armenia, Yugo-Slavia, and King Hussein—Signature of the Treaty – 169—271 VII. THE DISMEMBERMENT OF THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE: 1. The Turco-Armenian Question - 274—304 2. The Pan-Turanian and Pan-Arabian Movements: Origin of Pan-Turanism—The Turks and the Arabs—The Hejaz—The Emir Feisal—The Question of Syria—French Operations in Syria— Restoration of Greater Lebanon—The Arabian World and the Caliphate—The Part played by Islam - 304—356 VIII. THE MOSLEMS OF THE FORMER RUSSIAN EMPIRE AND TURKEY: The Republic of Northern Caucasus—Georgia and Azerbaïjan—The Bolshevists in the Republics of Caucasus and of the Transcaspian Isthmus—Armenians and Moslems - 357—369 IX. TURKEY AND THE SLAVS: Slavs versus Turks—Constantinople and Russia - 370—408 2 THE TURKS AND EUROPE I THE TURKS The peoples who speak the various Turkish dialects and who bear the generic name of Turcomans, or Turco-Tatars, are distributed over huge territories occupying nearly half of Asia and an important part of Eastern Europe. -

Architectural Mimicry and the Politics of Mosque Building: Negotiating Islam and Nation in Turkey

The Journal of Architecture ISSN: 1360-2365 (Print) 1466-4410 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rjar20 Architectural mimicry and the politics of mosque building: negotiating Islam and Nation in Turkey Bülent Batuman To cite this article: Bülent Batuman (2016) Architectural mimicry and the politics of mosque building: negotiating Islam and Nation in Turkey, The Journal of Architecture, 21:3, 321-347, DOI: 10.1080/13602365.2016.1179660 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13602365.2016.1179660 Published online: 17 May 2016. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 43 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rjar20 Download by: [Bilkent University] Date: 24 June 2016, At: 05:51 321 The Journal of Architecture Volume 21 Number 3 Architectural mimicry and the politics of mosque building: negotiating Islam and Nation in Turkey Bülent Batuman Department of Urban Design and Landscape Architecture, Bilkent University, Turkey (Author’s e-mail address: [email protected]) This paper discusses the politics of mosque architecture in modern Turkey. The classical Ottoman mosque image has been reproduced in state-sponsored mosques throughout the second half of the twentieth century. Defining this particular design strategy as architectural mimicry, I discuss the emergence of this image through the negotiation between the nation- state and the ‘nationalist conservative’ discourse within the context of Cold War geopolitics. Comparing the Turkish case with the Islamic post-colonial world, I argue that the prevalence of architectural mimicry is related to the nostalgia it generates. -

Stories of the Prophets

Stories of the Prophets Written by Al-Imam ibn Kathir Translated by Muhammad Mustapha Geme’ah, Al-Azhar Stories of the Prophets Al-Imam ibn Kathir Contents 1. Prophet Adam 2. Prophet Idris (Enoch) 3. Prophet Nuh (Noah) 4. Prophet Hud 5. Prophet Salih 6. Prophet Ibrahim (Abraham) 7. Prophet Isma'il (Ishmael) 8. Prophet Ishaq (Isaac) 9. Prophet Yaqub (Jacob) 10. Prophet Lot (Lot) 11. Prophet Shuaib 12. Prophet Yusuf (Joseph) 13. Prophet Ayoub (Job) 14 . Prophet Dhul-Kifl 15. Prophet Yunus (Jonah) 16. Prophet Musa (Moses) & Harun (Aaron) 17. Prophet Hizqeel (Ezekiel) 18. Prophet Elyas (Elisha) 19. Prophet Shammil (Samuel) 20. Prophet Dawud (David) 21. Prophet Sulaiman (Soloman) 22. Prophet Shia (Isaiah) 23. Prophet Aramaya (Jeremiah) 24. Prophet Daniel 25. Prophet Uzair (Ezra) 26. Prophet Zakariyah (Zechariah) 27. Prophet Yahya (John) 28. Prophet Isa (Jesus) 29. Prophet Muhammad Prophet Adam Informing the Angels About Adam Allah the Almighty revealed: "Remember when your Lord said to the angels: 'Verily, I am going to place mankind generations after generations on earth.' They said: 'Will You place therein those who will make mischief therein and shed blood, while we glorify You with praises and thanks (exalted be You above all that they associate with You as partners) and sanctify You.' Allah said: 'I know that which you do not know.' Allah taught Adam all the names of everything, then He showed them to the angels and said: "Tell Me the names of these if you are truthful." They (angels) said: "Glory be to You, we have no knowledge except what You have taught us. -

Türbe Mekâni, Türbe Kültürü

T.C. MALTEPE ÜNİVERSİTESİ SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENSTİTÜSÜ SOSYOLOJİ ANABİLİM DALI TÜRBE MEKÂNI, TÜRBE KÜLTÜRÜ: İSTANBUL’DA ÜÇ TÜRBEDE YAPILAN NİTELİKSEL ARAŞTIRMA, 2013 YÜKSEK LİSANS TEZİ AYŞE AYSUN ÇELİK 10 11 27 207 Danışman Öğretim Üyesi: Prof. Dr. Emine İNCİRLİOĞLU İstanbul, Ekim, 2013 ÖNSÖZ Öncelikle İstanbul şehrine duyduğum merak, ilgi ve sevgi araştırma konumun seçiminde önemli bir rol oynadı. İstanbul’un zengin kültür yapısıyla sosyoloji alanını nasıl bir araya getirebileceğimi düşünürken İstanbul türbelerinin zengin bir araştırma sahası olarak bunu sağlayabileceğine karar verdim. Aziz Mahmut Hüdayi, Eyüp Sultan ve Telli Baba türbelerinde ziyaretçilerin duygu dünyaları üzerinden, türbe mekânına yüklenen anlam ve bu mekânda oluşan kültürü ortaya koymaya çalıştım. Araştırma, türbe mekânlarında sürekli bir hareketlilik ve yaşayan bir kültür olduğunu ortaya koydu. Bu çalışmanın oluşmasında emeği geçen, ders aldığım değerli yüksek lisans hocalarıma, tezimi onaylayan değerli jüri hocalarım Prof. Dr. Bahattin Akşit, Yrd. Doç. Dr. Erkan Çav ve bilhassa tezimin hem yazım hem de saha çalışması olmak üzere her aşamasında her an yanımda olan değerli danışman hocam Prof. Dr. Emine İncirlioğlu’na teşekkürlerimi sunuyorum. Verdikleri her türlü destek için sevgili anne ve babam Meryem-Aziz Partanaz’a, eşim Zekeriya’ya, evlatlarım özellikle saha çalışması ve diğer aşamalarda yardımlarıyla yanımda olan sosyoloji öğrencisi kızım Sena’ya, Eren’e ve Revna’ya çok teşekkür ediyorum. ÖZET Türbe mekânı incelenerek orada oluşan kültürü anlamak bu çalışmanın amacını oluşturdu. İstanbul’un türbe zenginliği ve çeşitliliğinden yola çıkılarak belirlenen Aziz Mahmut Hüdayi, Eyüp Sultan ve Telli Baba türbeleri araştırma sahası olarak seçildi. Her türbede 10’ar olmak üzere toplam 30 derinlemesine görüşme yapıldı. Araştırma türbelerde yapılan gözlemlerle zenginleştirildi.