Pipeda: a Constitutional Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

225 Watertight Compartments: Getting Back to the Constitutional Division of Powers I. Introduction

GETTING BACK TO THE CONSTITUTIONAL DIVISION OF POWERS 225 WATERTIGHT COMPARTMENTS: GETTING BACK TO THE CONSTITUTIONAL DIVISION OF POWERS ASHER HONICKMAN* This article offers a fresh examination of the constitutional division of powers. The author argues that sections 91 and 92 of the Constitution Act, 1867 establish exclusive jurisdictional spheres — what the Privy Council once termed “watertight compartments.” This mutual exclusivity is emphasized and reinforced throughout these sections and leaves very little room for legitimate overlap. While some degree of overlap is permissible under this scheme — particularly incidental effects, genuine double aspects, and limited ancillary powers — overlap must be constrained in a principled fashion to comply with the exclusivity principle. The modern trend toward flexibility and freer overlap is contrary to the constitutional text. The author argues that while some deviation from the text is inevitable due to the presumption of constitutionality and stare decisis, the Supreme Court should return to a more exclusivist footing in accordance with the text. TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ............................................. 226 II. THE EXCLUSIVITY PRINCIPLE .................................. 227 A. FROM QUEBEC TO THE BRITISH PARLIAMENT ................. 227 B. THE NON OBSTANTE CLAUSE AND THE DEEMING PROVISION ...... 231 C. CONCURRENT POWERS ................................... 234 III. PITH AND SUBSTANCE AND LEGITIMATE OVERLAP ................. 235 A. INTERJURISDICTIONAL IMMUNITY ......................... -

The Constitutional Status of Yukon— a Normative Analysis

Research Article The Constitutional Status of Yukon— A Normative Analysis Pamela Muir* Abstract: Because Yukon is established by an Act of Parliament, is it possible Ottawa could abolish it or alter the government’s powers at will? The question of the legal position of Yukon in the federation is not straightforward. This article considers three pillars supporting the normative constitutional status of Yukon. The fi rst is a review of functionality, which suggests that today Yukon operates essentially like a province. The second pillar is permanence. It is suggested that the structure of public government, the democratic rights of Yukoners, and the rights of Yukon First Nations, together operate to limit Parliament’s power to unilaterally change the Yukon Act without the agreement of the people of Yukon. The fi nal pillar is sovereignty. As a result of devolution and responsible government, it is suggested that the Yukon government’s sphere of power is now protected from unilateral interference by Parliament. While there has been no constitutional amendment, these pillars support an interpretation that the “constitution-in-practice” has been altered. At the same time, the majority of Yukon First Nations have constitutionally protected rights and are now self- governing. This article concludes that the traditional binary view of the federation comprised of provinces and the federal government needs to be reimagined. The normative constitutional framework must embrace a broader vision that accommodates asymmetries in status and authority, acknowledges a permanent and sovereign place for Yukon and the other territories, and makes space for participation by Indigenous peoples in governance of the federation. -

Desgagnés Transport Inc. V. Wärtsilä Canada Inc., 2019 SCC 58 APPEAL HEARD: January 24, 20

SUPREME COURT OF CANADA CITATION: Desgagnés Transport Inc. v. Wärtsilä APPEAL HEARD: January 24, 2019 Canada Inc., 2019 SCC 58 JUDGMENT RENDERED: November 28, 2019 DOCKET: 37873 BETWEEN: Desgagnés Transport Inc., Desgagnés Transarctik Inc., Navigation Desgagnés Inc., Lloyds Underwriters and Institute of Lloyds Underwriters (ILU) Companies Subscribing to Policy Number B0856 09h0016 and Aim Insurance (Barbados) SCC Appellants and Wärtsilä Canada Inc. and Wärtsilä Nederland B.V. Respondents - and - Attorney General of Ontario and Attorney General of Quebec Interveners CORAM: Wagner C.J. and Abella, Moldaver, Karakatsanis, Gascon, Côté, Brown, Rowe and Martin JJ. JOINT REASONS FOR JUDGMENT: Gascon, Côté and Rowe JJ. (Moldaver, Karakatsanis and (paras. 1 to 107) Martin JJ. concurring) JOINT CONCURRING REASONS: Wagner C.J. and Brown J. (Abella J. concurring) (paras. 108 to 193) NOTE: This document is subject to editorial revision before its reproduction in final form in the Canada Supreme Court Reports. DESGAGNÉS TRANSPORT INC. v. WÄRTSILÄ CANADA INC. Desgagnés Transport Inc., Desgagnés Transarctik Inc., Navigation Desgagnés Inc., Lloyds Underwriters and Institute of Lloyds Underwriters (ILU) Companies Subscribing to Policy Number B0856 09h0016 and Aim Insurance (Barbados) SCC Appellants v. Wärtsilä Canada Inc. and Wärtsilä Nederland B.V. Respondents and Attorney General of Ontario and Attorney General of Quebec Interveners Indexed as: Desgagnés Transport Inc. v. Wärtsilä Canada Inc. 2019 SCC 58 File No.: 37873. 2019: January 24; 2019: November -

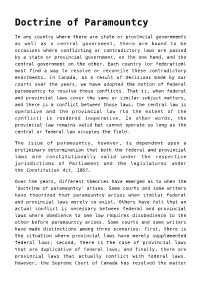

Doctrine of Paramountcy,B.C. Premier Vows to Shut Down Northern

Doctrine of Paramountcy In any country where there are state or provincial governments as well as a central government, there are bound to be occasions where conflicting or contradictory laws are passed by a state or provincial government, on the one hand, and the central government on the other. Each country (or federation) must find a way to resolve or reconcile these contradictory enactments. In Canada, as a result of decisions made by our courts over the years, we have adopted the notion of federal paramountcy to resolve these conflicts. That is, when federal and provincial laws cover the same or similar subject matters, and there is a conflict between those laws, the central law is operative and the provincial law (to the extent of the conflict) is rendered inoperative. In other words, the provincial law remains valid but cannot operate so long as the central or federal law occupies the field. The issue of paramountcy, however, is dependent upon a preliminary determination that both the federal and provincial laws are constitutionally valid under the respective jurisdictions of Parliament and the legislatures under the Constitution Act, 1867. Over the years, different theories have emerged as to when the ‘doctrine of paramountcy’ arises. Some courts and some writers have theorized that paramountcy arises when similar federal and provincial laws merely co-exist. Others have felt that an actual conflict is necessary between federal and provincial laws where obedience to one law requires disobedience to the other before paramountcy arises. Some courts and some writers have made distinctions among three scenarios: first, there is the situation where provincial laws have merely supplemented federal laws; second, there is the case of provincial laws that are duplicative of federal laws; and finally, there are provincial laws that actually conflict with federal laws. -

Client Bulletin

JUNE 16, 2016 CLIENT BULLETIN SUPREME COURT CONFIRMS EXCLUSIVE FEDERAL AUTHORITY TO REGULATE THE LOCATION OF RADIOCOMMUNICATION ANTENNA SYSTEMS The Supreme Court of Canada has given judgment in Rogers Communications Inc. v. Chateauguay (City), 2016 SCC 23, holding that the City lacked the constitutional jurisdiction to regulate the location of radiocommunication antenna systems. The case began in the fall of 2007 when Rogers entered into a lease of property in Chateauguay with the intention of constructing a new antenna system on the property to fill gaps in its wireless network. After entering the lease, Rogers applied for site approval under the federal Radiocommunication Act, which triggered a requirement that Rogers submit to a 120-day public consultation process as set out in the federal Radiocommunications and Broadcasting Circular (CPC-2-0-03). When Rogers notified the City of its intentions, Chateauguay expressed concern about the proposed installation, citing concerns about the visual impact of the antenna system and the potential for adverse health and safety consequences. After several rounds of consultation, numerous communications with the applicable federal Minister and even the initiation of expropriation proceedings by the City to acquire an alternative site for use by Rogers, the federal Minister issued an approval in 2010 for the construction of the antenna system on the property leased by Rogers in 2007. Chateauguay responded by issuing a “notice of reserve” under its enabling legislation prohibiting all construction on the property for a period of two years. Rogers then initiated legal proceedings challenging the validity of the notice of reserve. The City took the position that the notice of reserve should be upheld under the double aspect doctrine of constitutional law, a doctrine under which a provincial law that affects a matter having a federal aspect may be found valid so long as it also deals with matters within provincial legislative competence. -

Congress's Article Iii Power and the Process Of

42738-nyu_95-6 Sheet No. 92 Side B 12/10/2020 14:19:35 \\jciprod01\productn\N\NYU\95-6\NYU604.txt unknown Seq: 1 9-DEC-20 16:52 CONGRESS’S ARTICLE III POWER AND THE PROCESS OF CONSTITUTIONAL CHANGE CHRISTOPHER JON SPRIGMAN* Text in Article III of the U.S. Constitution appears to give to Congress authority to make incursions into judicial supremacy, by restricting (or, less neutrally, “strip- ping”) the jurisdiction of federal courts. Article III gives Congress authority to make “exceptions” to the Supreme Court’s appellate jurisdiction. Article III also gives Congress discretion whether to “ordain and establish” lower federal courts. Congress’s power to create or abolish these courts would seem to include the power to create them but to limit their jurisdiction, and that is how the power has histori- cally been understood. Is Congress’s power to remove the jurisdiction of federal courts in effect a legisla- tive power to choose the occasions on which federal courts may, and may not, have the final word on the meaning of the Constitution? That is a question on which the Supreme Court has never spoken definitively. In this Article I argue that Congress, working through the ordinary legislative process, may remove the jurisdiction of federal and even state courts to hear cases involving particular questions of federal law, including cases that raise questions under the Federal Constitution. Understood this way, the implications of Con- gress’s Article III power are profound. Congress may prescribe, by ordinary legis- lation, constitutional rules in areas where the meaning of the Constitution is unsettled. -

Supreme Court of Canada Citation

SUPREME COURT OF CANADA CITATION: Reference re Greenhouse APPEALS HEARD: September 22, 23, Gas Pollution Pricing Act, 2021 SCC 2020 11 JUDGMENT RENDERED: March 25, 2021 DOCKETS: 38663, 38781, 39116 BETWEEN: Attorney General of Saskatchewan Appellant and Attorney General of Canada Respondent - and - Attorney General of Ontario, Attorney General of Quebec, Attorney General of New Brunswick, Attorney General of Manitoba, Attorney General of British Columbia, Attorney General of Alberta, Progress Alberta Communications Limited, Canadian Labour Congress, Saskatchewan Power Corporation, SaskEnergy Incorporated, Oceans North Conservation Society, Assembly of First Nations, Canadian Taxpayers Federation, Canada’s Ecofiscal Commission, Canadian Environmental Law Association, Environmental Defence Canada Inc., Sisters of Providence of St. Vincent de Paul, Amnesty International Canada, National Association of Women and the Law, Friends of the Earth, International Emissions Trading Association, David Suzuki Foundation, Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation, Smart Prosperity Institute, Canadian Public Health Association, Climate Justice Saskatoon, National Farmers Union, Saskatchewan Coalition for Sustainable Development, Saskatchewan Council for International Cooperation, Saskatchewan Environmental Society, SaskEV, Council of Canadians: Prairie and Northwest Territories Region, Council of Canadians: Regina Chapter, Council of Canadians: Saskatoon Chapter, New Brunswick Anti-Shale Gas Alliance, Youth of the Earth, Centre québécois du droit de l’environnement, -

Law 435 Can Constitutional

LAW 435 CAN CONSTITUTIONAL INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................... 1 THE ELEMENTS OF THE CANADIAN CONSTITUTION ................................................................ 1 THE SOURCES OF THE CANADIAN CONSTITUTION ................................................................... 1 REFERENCE CASES ............................................................................................................................. 1 CONSTITUTIONAL PRINCIPLES .............................................................................................................. 1 Reference re Secession of Quebec ......................................................................................................... 1 Reference re Senate Reform .................................................................................................................. 2 CONSTITUTIONAL INTERPRETATION ................................................................................................... 2 UNWRITTEN CONSTITUTIONAL PRINCIPLES .............................................................................. 2 Reference re Meaning of the Word “Persons” in Section 24 of the British North America Act, 1867 . 2 Edwards v Canada (Attorney General) – Living Tree .......................................................................... 3 Constitutional Interpretation and Original Intent – Justice Ian Binnie ........................................... -

Federalism and Health Care in Canada: a Troubled Romance?

Schulich School of Law, Dalhousie University Schulich Law Scholars Research Papers, Working Papers, Conference Papers Faculty Scholarship 6-1-2017 Federalism and Health Care in Canada: A Troubled Romance? University of Ottawa Law RPS Submitter University of Ottawa - Common Law Section, [email protected] Colleen M. M. Flood University of Ottawa - Common Law Section, [email protected] Bryan P. Thomas University of Toronto - Faculty of Law, [email protected] William Lahey Dalhousie University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.schulichlaw.dal.ca/working_papers Recommended Citation RPS Submitter, University of Ottawa Law; Flood, Colleen M. M.; Thomas, Bryan P.; and Lahey, William, "Federalism and Health Care in Canada: A Troubled Romance?" (2017). Research Papers, Working Papers, Conference Papers. 17. https://digitalcommons.schulichlaw.dal.ca/working_papers/17 This Working Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Schulich Law Scholars. It has been accepted for inclusion in Research Papers, Working Papers, Conference Papers by an authorized administrator of Schulich Law Scholars. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Federalism and Health Care in Canada: A Troubled Romance? Colleen Flood, William Lahey & Bryan Thomas∗ Forthcoming in The Oxford Handbook of the Canadian Constitution, 2017 DRAFT VERSION – NOT FOR CITATION 1. Introduction Canada’s efforts to offer a modern health care system to its people are shaped, complicated, and in many ways hindered, by interpretations of federal/provincial divisions of power laid out in the Constitution Act, 1867 (the 1867 Act). Given its vintage, the 1867 Act has relatively little to say directly with respect to the health sector, which has since Confederation evolved into an enormously important area of the economy and of government activity. -

Equal Autonomy in Canadian Federalism: the Continuing Search for Balance in the Interpretation of the Division of Powers

The Supreme Court Law Review: Osgoode’s Annual Constitutional Cases Conference Volume 54 (2011) Article 20 Equal Autonomy in Canadian Federalism: The Continuing Search for Balance in the Interpretation of the Division of Powers Bruce Ryder Osgoode Hall Law School of York University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/sclr This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Citation Information Ryder, Bruce. "Equal Autonomy in Canadian Federalism: The onC tinuing Search for Balance in the Interpretation of the Division of Powers." The Supreme Court Law Review: Osgoode’s Annual Constitutional Cases Conference 54. (2011). https://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/sclr/vol54/iss1/20 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Osgoode Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in The uS preme Court Law Review: Osgoode’s Annual Constitutional Cases Conference by an authorized editor of Osgoode Digital Commons. Equal Autonomy in Canadian Federalism: The Continuing Search for Balance in the Interpretation of the Division of Powers Bruce Ryder∗ I. INTRODUCTION During most of the past decade, the justices of the Supreme Court of Canada have achieved and maintained a remarkable degree of consensus around their approach to the interpretation of the division of legislative powers in the Constitution Act, 1867.1 Since Beverley McLachlin’s appointment as Chief Justice in January 2000, the Court has been unanimous in its disposition of division of powers issues in 25 rulings or reference opinions.2 The Court was divided on the disposition of a division of powers issue in only one case between 2000 and 2008.3 ∗ Associate Professor and Assistant Dean First Year, Osgoode Hall Law School, York University. -

Beyond Umpire and Arbiter: Courts As Facilitators of Intergovernmental Dialogue in Division of Powers Cases in Canada

Beyond Umpire and Arbiter: Courts as Facilitators of Intergovernmental Dialogue in Division of Powers Cases in Canada Wade Kenneth Wright Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of the Science of Law in the School of Law COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2014 © 2014 Wade Kenneth Wright All rights reserved ABSTRACT Beyond Umpire and Arbiter: Courts as Facilitators of Intergovernmental Dialogue in Division of Powers Cases in Canada Wade Kenneth Wright The courts in Canada have often been cast, by both courts and legal scholars, as ‘umpires’ or ‘arbiters’ of the federal-provincial division of powers – umpires or arbiters that have the exclusive, or at least decisive, authority to clarify and enforce, and resolve disputes about, ‘who does what’ in the federal system. However, the image conveyed by these metaphors underestimates the role that the federal and provincial political branches play in the federal system, by working out their own solutions, in the intergovernmental arena, both directly and indirectly, where questions and disputes arise about how jurisdiction is and should be allocated. The image conveyed by the umpire or arbiter metaphors also sits uncomfortably with the facilitative role that the Supreme Court of Canada has carved out for itself in its recent division of powers decisions, a role that casts the courts as facilitators of these instances of intergovernmental dialogue. This doctoral dissertation challenges, and moves beyond, the umpire and arbiter metaphors. It examines the political safeguards available to the provinces in Canada to prevent, or limit, perceived federal encroachments on provincial jurisdiction, in the process highlighting the role that the political branches play in Canada in working out their own allocations of jurisdiction, outside of the courts. -

Hogg's Theory of Judicial Review

OVERVIEW Is Canada understood to be a mononational or multinational federation? What role has the Supreme Court of Canada (SCC) played in this understanding? Traditionally, Canadian federalism, and its evolution, is understood in terms of decentralization versus centralization. Canada, a politically and ethnically diverse nation, seen in its Multiculturalism policy, its Quebec factor and its regionalism issue, is a nation struggling with its identity; this is most evident in the many attempts at constitutional reform aiming to reflect its political society. Most recent examples include the Meech Lake Accord, the Charlottetown Accord and the Calgary Declaration. In essence, Canadians are debating whether Canada is a one nation, a two nation or a multinational state? Taking this into consideration, why not expand the understanding of Canadian federalism from centralized versus decentralized, and look at it in terms of mononational versus multinational?1 How Canada identifies itself politically very much rests on how its people, more specifically, its political actors, conceptualize federalism. Conceptualizations of federalism vary from government to government, from province to province and from individual to individual. Essentially however, one’s conceptualization of Canadian federalism rests in one’s belief of what 1 conceptions of federalism in the mononational fashion stress the political structure of federalism. That is to say, focus is placed on the division of powers, written in a constitution and reflected in the federal institution, and the assurance of autonomy for each level of government, within its sphere of power. Implicit is the hierarchy of governments, which usually translates into a stronger (and more important) central government.