Understanding School Shoppers in Detroit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2008-2009 Bill Witt

2008-2009 Title 1 Schools Required to Offer Supplemental Educational Services (SES) Title I schools that have not made Adequate Yearly Progress (AYP) for three or more consecutive years are required by the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001 (NCLB) to offer free tutoring to eligible students. District Name School Name Phase Academy for Business and Technology Academy for Business and Technology High 4 School Academy of Oak Park Academy of Oak Park - High School 5 Aisha Shule/WEB Dubois Prep. Academy Aisha Shule/WEB Dubois Prep. Academy 2 School School Benton Harbor Area Schools Hull Middle School 6 Buena Vista School District Buena Vista High School 4 Ricker Middle School 5 Casa Richard Academy Casa Richard Academy 4 Casman Alternative Academy Casman Alternative Academy 3 Center for Literacy and Creativity Center for Literacy and Creativity 2 Cesar Chavez Academy Cesar Chavez High School 2 Detroit Academy of Arts and Sciences Detroit Academy of Arts and Sciences High 2 School Detroit City School District Barbara Jordan Elementary 5 Barbour Magnet Middle School 8 Beckham, William Academy 6 Boykin Continuing Ed. Center 5 Boynton Elementary-Middle School 2 Central High School 5 Chadsey High School 5 Cleveland Middle School 8 Cody High School 5 Columbus Middle School 6 Communication and Media Arts HS 3 Cooley High School 5 Cooley North Wing 2 Courtis Elementary School 5 Crockett High School 4 Crosman Alternative High School 5 Denby High School 5 Detroit High School for Technology 2 Douglass Academy 4 Drew Middle School 8 Page 1 of 3 District -

New Look, Expansion Coming to Canton 6

Win a health} choppinl?os g spree! Win a healthy Loving care shopping spree at Buscb^with Peter At Angela Hospice, and f'Peter's volunteers provide ies ease respite from the waiting. Page C1 inside today's Observer ge C3. Your hometown newspaper serving Canton for 29 years Hope CANTON October is Breasl Cancer Awareness SUNDAY Month and new pro- October 5,2003 cedures give new 75 cents hope. Health, 06 VOLUME 29 NUMBER www.hometowhlife.com ©20Q3 HOMETOWN COMMUNICATIONS NETWORK I New look, expansion coming to Canton 6 BY JACK GLADDEN said Matt Johnson, marketing/training comforting seat cushions and molded Once the present building is redone, a STAFF WRITER manager for Goodrich Quality Theaters lumbar support backs. 5,400-square-foot addition will be con- of Grand Rapids which owns Canton 6. Stadium seating, which consists of structed on the back of the building that If the Canton 7 sounds like a radical "The first will be the remodeling of the concrete risers in every row of seats, will comprise the seventh auditorium. group from the 1960s, it's not. It's the existing building and the second will be allows patrons to have a heads-and- That will be a 312-seat state of the art new name of the Canton 6, the Ford the expansion." shoulders view above people in the row auditorium with a 50-foot wide screen. aise cash Road Theater which will be undergoing All six existing auditoriums will be in front of them. The project follows the announce- grSSgpSi an extensive remodeling and expansion refurbished and equipped with stadium Johnson said the theater will remain ment by Emagine Theaters that it is Tuesday, Oct. -

Michigan AHEC Regions Needs Assessment Summary Report

Michigan AHEC Regions Needs Assessment Summary Report Prepared by Wayne State University Center for Urban Studies July 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS Southeast Michigan Region 1 AHEC Needs Assessment Mid‐Central Michigan Region 26 AHEC Needs Assessment Northern Lower Michigan Region 44 AHEC Needs Assessment Upper Peninsula Michigan Region 61 AHEC Needs Assessment Western Michigan Region 75 AHEC Needs Assessment Appendix 98 AHEC Needs Assessment Southeast Michigan Region Medically Underserved Summary Table 2 Medically Underserved Areas and Populations 3 Healthcare Professional Shortage Areas 4 Primary Care Physicians 7 All Clinically‐Active Primary Care Providers 8 Licensed Nurses 10 Federally Qualified Health Centers 11 High Schools 16 Health Needs 25 1 Medically Underserved Population Southeast Michigan AHEC Region Age Distribution Racial/Ethnic Composition Poverty Persons 65 Years of American Indian or Persons Living Below Children Living Below Persons Living Below Age and Older (%) Black (%) Alaska Native (%) Asian (%) Hispanic (%) Poverty (%) Poverty (%) 200% Poverty (%) Michigan 14.53 15.30 1.40 3.20 4.60 16.90 23.70 34.54 Genesee 14.94 22.20 1.50 1.40 3.10 21.20 32.10 40.88 Lapeer 14.68 1.50 1.00 0.60 4.30 11.60 17.20 30.48 Livingston 13.11 0.80 1.00 1.00 2.10 6.00 7.30 17.53 Macomb 14.66 10.80 1.00 3.90 2.40 12.80 18.80 28.72 Monroe 14.64 2.90 0.90 0.80 3.20 11.80 17.50 28.99 Oakland 13.90 15.10 1.00 6.80 3.60 10.40 13.80 22.62 St. -

DETROIT BOARD of EDUCATION with Members of the Community Title VI Complaint Against Governor Rick Snyder

ABRIDGED VERSION DETROIT BOARD OF EDUCATION with Members of the Community Title VI Complaint Against Governor Rick Snyder July 27, 2015 1 2 3 4 Public education in America made this country great, but the racist tidal wave dissolving "Urban" schools in Michigan lead by Governor Snyder is the New Trail of Tears. Under this governor, urban schools have deteriorated into community eyesores and crime havens which are destroying the fabric of minority neighborhoods, and being replaced by experimental private models which have been proven ill equipped to provide quality learning environments. These institutions deny students with learning disabilities and other challenges an equal opportunity to an education, creating truly separate and unequal systems between white and black once again. Earl Rickman Past President, National Association of School Boards 5 TIMELINE The State of Michigan has been in authority over the Detroit Public Schools for approximately 13 of the last 16 years and is a recipient of Federal funds. Detroit Public Schools is a majority-minority district with the highest concentration of minorities of any city of 100,000 residents according to the 2010 US Census. 1994 In 1994, residents approved a $1.5 billion dollar capital bond program for Detroit Public Schools, which they will be paying for until at least 2033. The original bond was to be used to repair and renovate school buildings to service a then stable student enrollment of 167,000 students. The control of the spending of the bond dollars was a hotly contested issue, where various parties tried to take planning and spending authority from the school board. -

Field Trip Attendance 25,000 20,000 15,000 10,000 5,000 - 2013 2014 2015

Oakland County Arts Authority Report 2015 2.3 – Governance–Arts Authorities shall have the right to appoint two voting members to serve on the Detroit Institute of Arts’ Board of Directors. Thomas Guastello and Jennifer Fischer maintained their seats on the DIA Board of Directors. Thomas Guastello served on the Investment Committee. Jennifer Fischer served on the Director Search Committee. 2.4.1–Privileges to County Residents–Free General Admission General Admission 2015 Admission Category Guests Comp-Oakland County Resident-Adult 47,293 Comp-Oakland County Resident-Youth 16,088 Comp-Oakland County Resident-Schools 11,108 Comp-Oakland County-Adult Group 1,394 Comp-Oakland County-Senior 4,276 Member Scans-Oakland County 28,011 Oakland County Resident Totals 108,170 2015 free admission to Oakland County residents represent a value of $ 620,238.50 2.4.2 – Student Services and Curriculum Development Since passage of the tri-county millage, DIA educators have significantly increased K–12 services in Oakland County and continue to exceed target participation numbers for students and teachers. Field trip options have expanded in response to teachers’ requests. Professional development most often brings together K–12 educators with museum educators to design specific curriculum resources in support of teachers’ student learning outcomes. Free Student Field Trips with Bus Transportation total of 19,645 students participated in no- cost field trips to the DIA in 2015, exceeding the 16,000 target. Field Trip Attendance 25,000 20,000 15,000 10,000 -

1981 Graduates Summary Entering Occ Fall 1981 0

1981 GRADUATES SUMMARY ENTERING OCC FALL 1981 0 A K L A N D C 0 M M U N I T Y C 0 L L E G E INSTITUTIONAL RESEARCH .. C. Bruce Martin, Executive Director Administrative & Academic Services Henry Freigruber, Systems Analyst Beverly Meirow Typist March 29, 1982 OAKLAND COUNTY HIGH SCHOOLS 1981 GRADUATES SUMMARY ENTERING OCC FALL, 1981 According to available statistics, Oakland County public high schools in the Oakland Community College service area graduated a total of 14,868 students during 1981; some 2,109 of that group enrolled at Oakland Community College in the Fall, 1981 - equivalent to 14 percent of the entire group. Oakland County private schools graduated a total of 2,027 students during the same period; some 171 of that group enrolled at Oakland Community College in the Fall, 1981 - equivalent to some 8 percent of the entire group. Over all, Oakland Community College had 13.5 percent of all 1981 service area high school graduates enroll during the Fall, 1981 semester. 1981 Public High Schools 14,868 Entered OCC 2,109 Percent 14 Private High Schools 2,027 Entered OCC 171 Paftceni 8 TOTAL - Public and Private 16,895 Entered OCC 2,280 Percent 13 . 5 OAKLAND COUNTY PUBLIC HIGH SCHOOLS 1981 GRADUATES ENTERING OCC FALL, 1981 1981 Adams High School 485 Entered OCC 74 Percent . 15 Andover High School 397 Entered OCC 39 Percent 10 Athens High School 497 Entered occ 95 Percent 19 Avondale· High School 213 Entered OCC 33 Percent 15 Berkley High School 373 Entered OCC 70 Percent 19 Brandon High School 197 Entered OCC 16 Percent 8 • Central High School 472 Entered OCC 60 Percent 13 Clarkston High School 491 Entered OCC 70 Percent 14 Clawson High School 268 Entered OCC 44 Percent 16 -2- OAKLAND COUNTY PUBLIC HIGH SCHOOLS 1981 GRADUATES ENTERING OCC FALL, 1981 1981 Dondero High School 360 Entered OCC 46 Percent . -

Free COVID-19 March Testing Schedule

Stay Safe. Get tested. Free COVID-19 March Testing Schedule Testing sites may close early or be canceled due to inclement weather or low turnout. Please see detroitk12.org/health for the most updated information. DATE PLACE TIME Tuesday, March 2 Golightly – Henry Ford Health System (HFHS) 10 a.m.- 6 p.m. Renaissance High School– WSU Mobile 11 a.m. – 3 p.m. Wednesday, March 3 Martin Luther King Jr. High School- WSU Mobile 2 p.m. – 6 p.m. Thursday, March 4 Western High School – WSU Mobile 11 a.m. – 3 p.m. Mackenzie Elementary Middle School – WSU Mobile 11 a.m. - 3 p.m. Tuesday, March 9 Golightly – Henry Ford Health System 10 a.m. – 6 p.m. Wednesday, March 10 Henry Ford High School – WSU Mobile 2 p.m. -6 p.m. Thursday, March 11 Denby High School – WSU Mobile 11 a.m. – 3 p.m. Academy of the Americas – 5680 Konkel St. - HFHS 10 a.m. - 3 p.m. Friday, March 12 Munger Elementary-Middle School – WSU Mobile 11 a.m. – 3 p.m. Tuesday, March 16 Golightly – Henry Ford Health System 10 a.m.- 6 p.m. Wednesday, March 17 Renaissance High School – WSU Mobile 2 p.m. – 6 p.m. Thursday, March 18 Mumford High School – WSU Mobile 11 a.m. – 6 p.m. Academy of the Americas – 5680 Konkel St. - HFHS 10 a.m. - 3 p.m. Friday, March 19 East English Village High School – WSU Mobile 11 a.m. – 3 p.m. Tuesday, March 23 Golightly – Henry Ford Health System 10 a.m.- 6 p.m. -

2019 Spring Student Head Count*

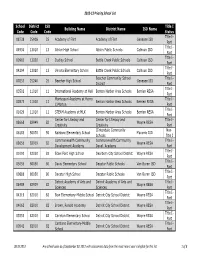

2019 Spring Student Head Count* Grade 10 Grade 11 Grade Combined Building Name District Name Total Total 12 Total Total 54th Street Academy Kelloggsville Public Schools 21 36 24 81 A.D. Johnston Jr/Sr High School Bessemer Area School District 39 33 31 103 Academic and Career Education Academy Academic and Career Education Academy 27 21 27 75 Academy 21 Center Line Public Schools 43 26 38 107 Academy for Business and Technology High School Academy for Business and Technology 41 17 35 93 Academy of Science Math and Technology Early College High School Mason County Central Schools 0 0 39 39 Academy of The Americas High School Detroit Public Schools Community District 39 40 14 93 Academy West Alternative Education Westwood Heights Schools 84 70 86 240 ACCE Ypsilanti Community Schools 28 48 70 146 Accelerated Learning Academy Flint, School District of the City of 40 16 11 67 ACE Academy - Jefferson site ACE Academy (SDA) 1 2 0 3 ACE Academy (SDA) -Glendale, Lincoln, Woodward ACE Academy (SDA) 50 50 30 130 Achievement High School Roseville Community Schools 3 6 11 20 Ackerson Lake Community Education Napoleon Community Schools 15 21 15 51 ACTech High School Ypsilanti Community Schools 122 142 126 390 Addison High School Addison Community Schools 57 54 60 171 Adlai Stevenson High School Utica Community Schools 597 637 602 1836 Adrian Community High School Adrian Public Schools 6 10 20 36 Adrian High School Adrian Public Schools 187 184 180 551 Advanced Technology Academy Advanced Technology Academy 106 100 75 281 Advantage Alternative Program -

Letter to the Community FALL 2019

2018-2019 • Annual Report Letter to the Community FALL 2019 According to Rudolf Steiner, the three components of a Waldorf education are a need for imagination, a sense of truth, and a feeling of responsibility. For 54 years, Detroit Waldorf School has nurtured these pillars of learning in thousands of students, who have entered society as creative, voracious, and responsible citizens of the world. It is our community that sustains DWS. Our parents, grandparents, alumni, teachers, and staff breathe life into our school day after day. We endured periods of uncertainty, and now we are navigating a period of unprecedented growth and demand. This next year is critical for our school to determine how we might increase our capacity and open our doors to more children. It is our challenge to ride this wave of interest in Waldorf education while also addressing the need for more Waldorf educators. In order to thrive, DWS requires more teachers and these teachers deserve fair compensation. DWS has endured because we have remained true to our mission and committed to the children who pass through our gate. As we celebrate 100 years of Waldorf education, I invite you to join me in committing anew to supporting our wonderful community. The fellowship and friendship Detroit Waldorf School has provided my family—and families like yours—is invaluable. Please consider giving in honor of all we have accomplished in the past five decades, and all we will achieve in the future. Sincerely, Dante King, PRESIDENT, BOARD OF TRUSTEES Our Students DWS ended the 2018-19 academic year with 254 enrolled students. -

Priority School List

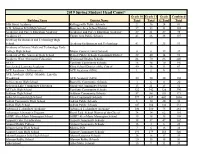

2012‐13 Priority School List School District ISD Title I Building Name District Name ISD Name Code Code Code Status Title I- 08738 25908 25 Academy of Flint Academy of Flint Genesee ISD Part Title I- 04936 13010 13 Albion High School Albion Public Schools Calhoun ISD Part Title I- 00965 13020 13 Dudley School Battle Creek Public Schools Calhoun ISD Part Title I- 04294 13020 13 Verona Elementary School Battle Creek Public Schools Calhoun ISD Part Beecher Community School Title I- 00253 25240 25 Beecher High School Genesee ISD District Part Title I- 03502 11010 11 International Academy at Hull Benton Harbor Area Schools Berrien RESA Part Montessori Academy at Henry Title I- 00373 11010 11 Benton Harbor Area Schools Berrien RESA C Morton Part Title I- 01629 11010 11 STEAM Academy at MLK Benton Harbor Area Schools Berrien RESA Part Center for Literacy and Center for Literacy and Title I- 08668 82949 82 Wayne RESA Creativity Creativity Part Clintondale Community Non- 06183 50070 50 Rainbow Elementary School Macomb ISD Schools Title I Commonwealth Community Commonwealth Community Title I- 08656 82919 82 Wayne RESA Development Academy Devel. Academy Part Title I- 01092 82030 82 Edsel Ford High School Dearborn City School District Wayne RESA Part Title I- 05055 80050 80 Davis Elementary School Decatur Public Schools Van Buren ISD Part Title I- 00888 80050 80 Decatur High School Decatur Public Schools Van Buren ISD Part Detroit Academy of Arts and Detroit Academy of Arts and Title I- 08489 82929 82 Wayne RESA Sciences Sciences Part Title I- 04319 82010 82 Bow Elementary-Middle School Detroit City School District Wayne RESA Part Title I- 04062 82010 82 Brown, Ronald Academy Detroit City School District Wayne RESA Part Title I- 05553 82010 82 Carleton Elementary School Detroit City School District Wayne RESA Part Carstens Elementary-Middle Title I- 00542 82010 82 Detroit City School District Wayne RESA School Part 08.19.2013 Any school open as of September 30, 2012 with assessment data from the most recent year is eligible for this list. -

Charter Schools

· ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY Profiles of For-Profit Education Management Organizations 2004-2005 Seventh-Annual Report by Alex Molnar, David Garcia, Carolyn Sullivan, Brendan McEvoy and Jamie Joanou Commercialism in Education Research Unit (CERU) Education Policy Studies Laboratory College of Education Division of Educational Leadership and Policy Studies Box 872411 Arizona State University Tempe, AZ 85287-2411 April 2005 EDUCATION POLICY STUDIES LABORATORY EPSL | Commercialism in Education Research Unit EPSL-0504-101-CERU http://edpolicylab.org Education Policy Studies Laboratory Division of Educational Leadership and Policy Studies College of Education, Arizona State University P.O. Box 872411, Tempe, AZ 85287-2411 Telephone: (480) 965-1886 Fax: (480) 965-0303 E-mail: [email protected] http://edpolicylab.org Profiles of For-Profit Education Management Organizations 2004-2005 Introduction In 2004-2005 the education management industry continued its decade-long expansion. More students were enrolled in schools managed by Education Management Organizations (EMOs) in 2004-2005 than at any time since the Commercialism in Education Research Unit (CERU) and the Education Policy Research Unit (EPRU) began tracking the industry in 1998-1999.1 The term EMO, originally coined by Wall Street analysts to describe the for-profit companies involved in the management and administration of public schools, is intended to reflect similarities between such companies and Health Maintenance Organizations (HMOs).2 For the purposes of this report, a company is considered an EMO if it is for-profit, manages a school that receives public funds, and operates under the same admissions rules as regular public schools. This year’s Profiles of For-Profit Education Management Organizations is the largest to date, listing 59 companies that manage 535 schools, enrolling approximately 239,766 students in 24 states and the District of Columbia. -

Youth Urban Agenda Program AGENDA-BUILDING GUIDE

WAYNE STATE UNIVERSITY Urban Agenda/Civic Literacy Project A Civic Education Program for Urban and Suburban Youth Implemented through Middle School, High School and Post-Secondary and Adult Education and Community Organizations Youth Urban Agenda Program AGENDA-BUILDING GUIDE YOU HAVE A VOICE . LET IT BE HEARD! Cover Layout: Tina Samaddar Photos: Ella Singer Edited by: Ella Singer & Tina Samaddar Check Out Our Web-Site!! www.urbanagenda.wayne.edu WSU-based non-profit organization promoting civic education in the schools and in the community WAYNE STATE UNIVERSITY Urban Agenda/Civic Literacy Project 2002 FAB Wayne State University Detroit, MI 48201 313 577 2235 313 993 3435(Fax) YOUTH URBAN AGENDA PROGRAM: An Introductory Packet Table of Contents: What is Civic Literacy? 3 About the Project . 4 The Curriculum 5 Michigan Content Standards and Draft Benchmarks as applied to Youth Urban Agenda Program 15 An Event: 17 October 27, 1998 Youth Urban Agenda Convention at Cobo Hall WAYNE STATE UNIVERSITY 2 Urban Agenda/Civic Literacy Project What is Civic Literacy? Civic Literacy is the knowledge of how to actively participate and initiate change in your community and the greater society. It is the foundation by which a democratic society functions: Citizen Power as a check and as a means to create avenues for peaceful change. Why an Agenda? · Civic participation not only encompasses voting in elections but also a consciousness about the issues that are most important to an individual and his or her community. Creating an agenda is an avenue to gather support and raise awareness for both community members and elected officials about what’s happening in the community.