Insiders and Outsiders on the Gay Community in Weimar Berlin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Bauhaus and Weimar Modernism

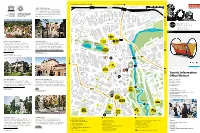

Buchenwald Memorial, Ettersburg Castle Sömmerda (B7 / B85) 100 m weimar UNESCO World Heritage 500 m Culture City of Europe The Bauhaus and its sites in Weimar and Dessau have been on the UNESCO list of World Heritage since 1996. There are three objects in Weimar: the main building of the Bauhaus University Weimar, the former School of Applied Arts and the Haus Am Horn. Tiefurt Mansion deutschEnglish Harry-Graf-Kessler-Str. 10 5 Tiefurt Mansion Bauhaus-Universität Weimar Nietzsche Archive B Jorge-Semprùn-Platz a Oskar-Schlemmer-Str. d The building ensemble by Henry van de Velde was Friedrich Nietzsche spent the last years of his life at H e Stèphane- r 1 s revolutionary in terms of architecture at the turn of the “Villa Silberblick”. His sister established the Nietzsche Archive f Hessel-Platz e l d century. These Art School buildings became the venue here after his death and had the interior and furnishings e r S where the State Bauhaus was founded in 1919, making designed by Henry van de Velde. The current exhibition is t r a ß “Weimar” and the “Bauhaus” landmarks in the history of entitled “Kampf um Nietzsche” (“Dispute about Nietzsche”). e modern architecture. Humboldtstrasse 36 13 Mon, Wed to Sun 2pm – 5pm Geschwister-Scholl-Strasse 2 Mon to Fri 10am – 6pm | Sat & Sun 10am – 4pm Über dem Kegeltor C o u d r a y s t Erfurt (B7) r a ß e Berkaer Bahnhof 8 CRADLE, DESIGN: PETER KELER, 1922 © KLASSIK STIFTUNG WEIMAR 17 Jena (B7) 3 Tourist Information Office Weimar Haus Hohe Pappeln Weimar Municipal Museum 20 16 Markt 10, 99423 Weimar The Belgian architect Henry van de Velde, the artistic The permanent exhibition of the Municipal Museum presents Tel + 49 (0) 3643 745 0 advisor of the grand duchy, built this house for his family of “Democracy from Weimar. -

CHAPTER 2 the Period of the Weimar Republic Is Divided Into Three

CHAPTER 2 BERLIN DURING THE WEIMAR REPUBLIC The period of the Weimar Republic is divided into three periods, 1918 to 1923, 1924 to 1929, and 1930 to 1933, but we usually associate Weimar culture with the middle period when the post WWI revolutionary chaos had settled down and before the Nazis made their aggressive claim for power. This second period of the Weimar Republic after 1924 is considered Berlin’s most prosperous period, and is often referred to as the “Golden Twenties”. They were exciting and extremely vibrant years in the history of Berlin, as a sophisticated and innovative culture developed including architecture and design, literature, film, painting, music, criticism, philosophy, psychology, and fashion. For a short time Berlin seemed to be the center of European creativity where cinema was making huge technical and artistic strides. Like a firework display, Berlin was burning off all its energy in those five short years. A literary walk through Berlin during the Weimar period begins at the Kurfürstendamm, Berlin’s new part that came into its prime during the Weimar period. Large new movie theaters were built across from the Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial church, the Capitol und Ufa-Palast, and many new cafés made the Kurfürstendamm into Berlin’s avant-garde boulevard. Max Reinhardt’s theater became a major attraction along with bars, nightclubs, wine restaurants, Russian tearooms and dance halls, providing a hangout for Weimar’s young writers. But Berlin’s Kurfürstendamm is mostly famous for its revered literary cafés, Kranzler, Schwanecke and the most renowned, the Romanische Café in the impressive looking Romanische Haus across from the Memorial church. -

LGBT Thou G H T and Cu LT Ur E

LGBT THOUGHT AND CUltURE at learn more alexanderstreet.com LGBT Thought and Culture LGBT Thought and Culture is an online resource hosting the key works and archival documentation of LGBT political and social movements throughout the 20th century and into the present day. LGBT Thought and Culture includes - Hirschfeld’s famous letter to students at • Rare books and major winners of the materials ranging from seminal texts, letters, Charlottenburg Institute of Technology. Stonewall Book Awards and Lambda periodicals, speeches, interviews, and • Additional collections from the Kinsey Literary Awards, many of which are no ephemera covering the political evolution Institute’s archives, including early longer in print: of gay rights to memoirs, biographies, transgender periodicals, organizational - The Homosexual in America, Donald poetry, and works of fiction that illuminate papers, and writings from Harry Corey, originally published in 1951 the lives of lesbian, gay, transgender, and Benjamin and John Money. - Imre: A Memorandum, Xavier Mayne, bisexual individuals and the community. • The One National Gay and Lesbian originally published in 1908 At completion, the database will contain Archive collections, including: - Left Out: The Politics of Exclusion, 150,000 pages of rich content essential to - The Bob Damron Address guides that Martin B. Duberman students and scholars of cultural studies, contain lists of gay friendly bars in Los - The Stone Wall, Mary Casal, originally history, women’s and gender studies, Angeles from 1966-1980. published in 1930 political science, American studies, social - The papers of gay rights pioneer and To ensure the highest caliber, most theory, sociology, and literature. Content peace activist Morris Kight. -

The Crisis Manager the Jacobsohn Era, 1914 –1938 INTRODUCTION

CHRONICLE 05 The crisis manager The Jacobsohn era, 1914 –1938 INTRODUCTION From the First World War to National Socialism A world in turmoil “Carpe diem” – seize the day. This Latin motto is carved over their positions. Beyond the factory gates, things on the gravestone of Dr. Willy Jacobsohn in Los Angeles were also far from peaceful: German society took a long and captures the essence of his life admirably. Given time to recover from the war. The period up until the the decades spanned by Jacobsohn’s career, this out- end of 1923 was scourged by unemployment, food and look on everyday life made a lot of sense: after all, housing shortages, and high inflation. The “Golden his career at Beiersdorf took place during what was Twenties” offered a brief respite, but even in the heyday arguably the most turbulent period in European history. of Germany’s first democracy, racist and anti-Semitic In fact, there are quite a few historians who describe feelings were simmering below the surface in society the period between 1914 and 1945 as the “second and politics, erupting in 1933 when the National Socia- Thirty Years War.” lists came to power. Jewish businessman Jacobsohn The First World War broke out shortly after Jacob- was no longer able to remain in Germany and, five years sohn joined the company in 1914. Although the war later, was even forced to leave Europe for America. ended four years later, Beiersdorf continued to suffer However, by then he had succeeded in stabilizing the crisis after crisis. Dr. Oscar Troplowitz and Dr. -

Urning: Representing Karl Heinrich Ulrichs and His Legacy Through the Mechanism of Theatre

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2019-06 Urning: Representing Karl Heinrich Ulrichs and His Legacy through the Mechanism of Theatre Diller, Ryan Diller, R. (2019). Urning: Representing Karl Heinrich Ulrichs and His Legacy through the Mechanism of Theatre (Unpublished master's thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/110571 master thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY Urning: Representing Karl Heinrich Ulrichs and His Legacy through the Mechanism of Theatre by Ryan Diller A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF FINE ARTS GRADUATE PROGRAM IN DRAMA CALGARY, ALBERTA JUNE, 2019 © Ryan Diller 2019 UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES The undersigned certify that they have read, and recommend to the Faculty of Graduate Studies for acceptance, a thesis entitled “Urning: Representing Karl Heinrich Ulrichs and His Legacy through the Mechanism of Theatre” submitted by Ryan Diller in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Fine Arts. ____________________________________________________________ Supervisor, Professor Clement Martini, Department of Drama ___________________________________________________________ Dr. Patrick James Finn, Examination Committee Member, Department of Drama ____________________________________________________________ Dr. -

A Study of the Space That Shaped Weimar Berlin Carrie Grace Latimer Scripps College

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Scripps Senior Theses Scripps Student Scholarship 2014 The lotP s of Alexanderplatz: A Study of the Space that Shaped Weimar Berlin Carrie Grace Latimer Scripps College Recommended Citation Latimer, Carrie Grace, "The lotsP of Alexanderplatz: A Study of the Space that Shaped Weimar Berlin" (2014). Scripps Senior Theses. Paper 430. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/scripps_theses/430 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Scripps Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scripps Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE PLOTS OF ALEXANDERPLATZ: A STUDY OF THE SPACE THAT SHAPED WEIMAR BERLIN by CARRIE GRACE LATIMER SUBMITTED TO SCRIPPS COLLEGE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS PROFESSOR MARC KATZ PROFESSOR DAVID ROSELLI APRIL 25 2014 Latimer 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements 3 Introduction 4 Chapter One: Berlin Alexanderplatz: The Making of the Central Transit Hub 8 The Design Behind Alexanderplatz The Spaces of Alexanderplatz Chapter Two: Creative Space: Alfred Döblin’s Berlin Alexanderplatz 23 All-Consuming Trauma Biberkopf’s Relationship with the Built Environment Döblin’s Literary Metropolis Chapter Three: Alexanderplatz Exposed: Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s Film 39 Berlin from Biberkopf’s Perspective Exposing the Subterranean Trauma Conclusion 53 References 55 Latimer 3 Acknowledgements I wish to thank all the people who contributed to this project. Firstly, to Professor Marc Katz and Professor David Roselli, my thesis readers, for their patient guidance, enthusiastic encouragement and thoughtful critiques. -

LGBT History

LGBT History Just like any other marginalized group that has had to fight for acceptance and equal rights, the LGBT community has a history of events that have impacted the community. This is a collection of some of the major happenings in the LGBT community during the 20th century through today. It is broken up into three sections: Pre-Stonewall, Stonewall, and Post-Stonewall. This is because the move toward equality shifted dramatically after the Stonewall Riots. Please note this is not a comprehensive list. Pre-Stonewall 1913 Alfred Redl, head of Austrian Intelligence, committed suicide after being identified as a Russian double agent and a homosexual. His widely-published arrest gave birth to the notion that homosexuals are security risks. 1919 Magnus Hirschfeld founded the Institute for Sexology in Berlin. One of the primary focuses of this institute was civil rights for women and gay people. 1933 On January 30, Adolf Hitler banned the gay press in Germany. In that same year, Magnus Herschfeld’s Institute for Sexology was raided and over 12,000 books, periodicals, works of art and other materials were burned. Many of these items were completely irreplaceable. 1934 Gay people were beginning to be rounded up from German-occupied countries and sent to concentration camps. Just as Jews were made to wear the Star of David on the prison uniforms, gay people were required to wear a pink triangle. WWII Becomes a time of “great awakening” for queer people in the United States. The homosocial environments created by the military and number of women working outside the home provide greater opportunity for people to explore their sexuality. -

THE COUDENHOVE-KALERGI PLAN – the GENOCIDE of the PEOPLES of EUROPE? (Excerpts) Identità News Team

RUNNYMEDE GAZETTE A Journal of the Democratic Resistance FEBRUARY 2016 EDITORIAL THE PROPHET REVEALED CONTENTS ENGLISH TRANSLATION OF SELECTIONS OF PRACTICAL IDEALISM (PRAKTISCHER IDEALISMUS) Count Richard Nicolaus Coudenhove-Kalergi; via Balder Blog RICHARD NIKOLAUS VON COUDENHOVE-KALERGI Wikipedia THE COUDENHOVE-KALERGI PLAN – THE GENOCIDE OF THE PEOPLES OF EUROPE? (Excerpts) Identità News Team TACKLING THE EU EMPIRE: A HANDBOOK FOR EUROPE’S DEMOCRATS, WHETHER ON THE POLITICAL RIGHT, LEFT OR CENTRE The Bruges Group WHO REALLY CONTROLS THE WORLD? Prof. Dr. Mujahid Kamran; Global Research; New Dawn Magazine 12 METHODS TO UNPLUG FROM THE MATRIX Phillip J. Watt; Waking Times; via Libertarian Alliance Blog GETTING THE IDEA OF GOVERNMENT AND POLITICAL AUTHORITY OUT OF YOUR MIND Makia Freeman; Activist Post “NEGATIVE” INTEREST RATES AND THE WAR ON CASH Liquidity Watch; Prof. Richard A. Werner; Rawjapan; via Critical Thinking GERMANY JOINS TREND TOWARD CASHLESS SOCIETY: “CASH CONTROLS” BAN TRANSACTIONS OVER €5,000, €500 EURO NOTE Tyler Durden; Activist Post THE COLLAPSE OF THE TOO BIG TO FAIL BANKS IN EUROPE IS HERE Michael Snyder; Activist Post -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- EDITORIAL THE PROPHET REVEALED We often recognise things we cannot name … a sound, a shape, a smell, an idea … Then suddenly, as if from the ether, a name for that perception suddenly appears. Then it is instant recognition … deja vu writ large. It was thus with Coudenhove-Kalergi. Having spent half a lifetime watching an unnamed influence at work … as if I was aware of some underground river undercutting the ground beneath our feet … last year I was at long last able to give it a name. -

The Evolution & Politics of First-Wave Queer Activism

“Glory of Yet Another Kind”: The Evolution & Politics of First-Wave Queer Activism, 1867-1924 GVGK Tang HIST4997: Honors Thesis Seminar Spring 2016 1 “What could you boast about except that you stifled my words, drowned out my voice . But I may enjoy the glory of yet another kind. I raised my voice in free and open protest against a thousand years of injustice.” —Karl Heinrich Ulrichs after being shouted down for protesting anti-sodomy laws in Munich, 18671 Queer* history evokes the familiar American narrative of the Stonewall Uprising and gay liberation. Most people know that lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people rose up, like other oppressed minorities in the sixties, with a never-before-seen outpouring of social activism, marches, and protests. Popular historical discourse has led the American public to believe that, before this point, queers were isolated, fractured, and impotent – relegated to the shadows. The postwar era typically is conceived of as the critical turning point during which queerness emerged in public dialogue. This account of queer history depends on a social category only recently invented and invested with political significance. However, Stonewall was not queer history’s first political milestone. Indeed, the modern LGBT movement is just the latest in a series of campaign periods that have spanned a century and a half. Queer activism dawned with a new lineage of sexual identifiers and an era of sexological exploration in the mid-nineteenth century. German lawyer Karl Heinrich Ulrichs was first to devise a politicized queer identity founded upon sexological theorization.2 He brought this protest into the public sphere the day he outed himself to the five hundred-member Association 1 Karl Heinrich Ulrichs, The Riddle of "Man-Manly" Love, trans. -

Uranianism by Ruth M

Uranianism by Ruth M. Pettis Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. Entry Copyright © 2004, glbtq, inc. Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com "Uranian" and "Uranianism" were early terms denoting homosexuality. They were in English use primarily from the 1890s through the first quarter of the 1900s and applied to concurrent and overlapping trends in sexology, social philosophy, and poetry, particularly in Britain. "Uranian" was a British derivation from "Urning," a word invented by German jurist Karl Heinrich Ulrichs in the 1860s. In a series of pamphlets Ulrichs proposed a scheme for classifying the varieties of sexual orientation, assuming their occurrence in natural science. He recognized three principal categories among males: "Dionings" (heterosexuals), "Urnings" (homosexuals), and "Uranodionings" (bisexuals), based on their preferences for sexual partners. (A fourth category, hermaphrodites, he acknowledged but dismissed as occurring too infrequently to be significant.) Ulrichs further subdivided Urnings into those who prefer effeminate males, masculine males, adolescent males, and a fourth category who repressed their natural yearnings and lived heterosexually. Those who applied Ulrichs' system felt the need for Top: Edward Carpenter. analogous terms for women, and devised the terms "Urningins" (lesbians) and Center: John Addington "Dioningins" (heterosexual women). Symonds. Above: Walt Whitman. Images courtesy Library The term "Uranian" also alludes to the discussion in Plato's Symposium of the of Congress Prints and "heavenly" form of love (associated with Aphrodite as the daughter of Uranus) Photographs Division. practiced by those who "turn to the male, and delight in him who is the more valiant and intelligent nature." This type of love was distinguished from the "common" form of love associated with heterosexual love of women. -

The Transgender-Industrial Complex

The Transgender-Industrial Complex THE TRANSGENDER– INDUSTRIAL COMPLEX Scott Howard Antelope Hill Publishing Copyright © 2020 Scott Howard First printing 2020. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be copied, besides select portions for quotation, without the consent of its author. Cover art by sswifty Edited by Margaret Bauer The author can be contacted at [email protected] Twitter: @HottScottHoward The publisher can be contacted at Antelopehillpublishing.com Paperback ISBN: 978-1-953730-41-1 ebook ISBN: 978-1-953730-42-8 “It’s the rush that the cockroaches get at the end of the world.” -Every Time I Die, “Ebolarama” Contents Introduction 1. All My Friends Are Going Trans 2. The Gaslight Anthem 3. Sex (Education) as a Weapon 4. Drag Me to Hell 5. The She-Male Gaze 6. What’s Love Got to Do With It? 7. Climate of Queer 8. Transforming Our World 9. Case Studies: Ireland and South Africa 10. Networks and Frameworks 11. Boas Constrictor 12. The Emperor’s New Penis 13. TERF Wars 14. Case Study: Cruel Britannia 15. Men Are From Mars, Women Have a Penis 16. Transgender, Inc. 17. Gross Domestic Products 18. Trans America: World Police 19. 50 Shades of Gay, Starring the United Nations Conclusion Appendix A Appendix B Appendix C Introduction “Men who get their periods are men. Men who get pregnant and give birth are men.” The official American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) Twitter account November 19th, 2019 At this point, it is safe to say that we are through the looking glass. The volume at which all things “trans” -

THE PERSECUTION of HOMOSEXUALS in NAZI GERMANY Kaleb Cahoon HIST 495: Senior Seminar May 1, 2017

THE PERSECUTION OF HOMOSEXUALS IN NAZI GERMANY Kaleb Cahoon HIST 495: Senior Seminar May 1, 2017 1 On May 6, 1933, a group of students from the College of Physical Education in Berlin arrived early in the morning to raid the office headquarters of the Institute for Sexual Research in Berlin. According to a contemporary anonymous report, the invading students “took up a military-style position in front of the house and then forced their way inside, with musical accompaniment… [and then] they smashed down the doors.”1 Once inside, the same group commenced to ransack the place: they “emptied inkwells, pouring ink onto various papers and carpets, and then set about the private bookcases” and then “took with them what struck them as suspicious, keeping mainly to the so-called black list.”2 Later that day, after the students had left “large piles of ruined pictures and broken glass” in their wake, a contingent of Storm Troopers arrived to complete the operation by confiscating nearly ten thousand books that they subsequently burned three days later.3 This raid was part of an overall campaign to purge “books with an un-German spirit from Berlin libraries,” undertaken early in the regime of the Third Reich. Their target, the Institute for Sexual Research founded by the pioneering German sexologist Magnus Hirschfeld, was one of the premier centers of progressive thought concerning human sexuality – most notably homosexuality – in the world.4 This episode raises a number of questions, including why Nazi leaders deemed this organization to possess “an un-German spirit” that thus warranted a thorough purge so early in the regime.5 The fact that Hirschfeld, like many other leading sexologists in Germany, was Jewish and that many Nazis thus regarded the burgeoning field of “Sexualwissenschaft, or the science of sex,” as “Jewish science” likely 1 “How Magnus Hirschfeld’s Institute for Sexual Science Was Demolished and Destroyed,” (1933) in The Third Reich Sourcebook, ed.