Grigol Robakidze University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Liam O'shea Phd Thesis

POLICE REFORM AND STATE-BUILDING IN GEORGIA, KYRGYZSTAN AND RUSSIA Liam O’Shea A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2014 Full metadata for this item is available in Research@StAndrews:FullText at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/5165 This item is protected by original copyright POLICE REFORM AND STATE-BUILDING IN GEORGIA, KYRGYZSTAN AND RUSSIA Liam O’Shea This thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment for the degree of PhD at the University oF St Andrews Date of Submission – 24th January 2014 1. Candidate’s declarations: I Liam O'Shea hereby certify that this thesis, which is approximately 83,500 words in length, has been written by me, and that it is the record of work carried out by me, or principally by myself in collaboration with others as acknowledged, and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree. I was admitted as a research student in October 2008 and as a candidate for the degree of PhD International Relations in November 2009; the higher study for which this is a record was carried out in the University of St Andrews between 2008 and 2014. Date …… signature of candidate ……… 2. Supervisor’s declaration: I hereby certify that the candidate has fulfilled the conditions of the Resolution and Regulations appropriate for the degree of PhD International Relations in the University of St Andrews and that the candidate is qualified to submit this thesis in application for that degree. -

Police Reform in Ukraine Since the Euromaidan: Police Reform in Transition and Institutional Crisis

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2-2019 Police Reform in Ukraine Since the Euromaidan: Police Reform in Transition and Institutional Crisis Nicholas Pehlman The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/3073 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Police Reform in Ukraine Since the Euromaidan: Police Reform in Transition and Institutional Crisis by Nicholas Pehlman A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Political Science in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2019 © Copyright by Nick Pehlman, 2018 All rights reserved ii Police Reform in Ukraine Since the Euromaidan: Police Reform in Transition and Institutional Crisis by Nicholas Pehlman This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Political Science in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Date Mark Ungar Chair of Examining Committee Date Alyson Cole Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Julie George Jillian Schwedler THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Police Reform in Ukraine Since the Euromaidan: Police Reform in Transition and Institutional -

A Picture of Judicial Reforms in the Transition Era

LIBERAL MISSION FOUNDATION Ekaterina Mishina THE LONG SHADOWS OF THE SOVIET PAST: A PICTURE OF JUDICIAL REFORMS IN THE TRANSITION ERA Moscow 2020 UDC 347.97/.99(47+57) Mishina E. The Long Shadows Of The Soviet Past: A Picture Of Judicial Reforms In The Transition Era / E. Mishina. — Moscow : Liberal Mission Foundation, 2020. — 196 p. ISBN 978-5-903135-74-5 The book addresses the specifics of the Soviet Constitutions and Soviet law (including early Soviet criminal law and family law). Special attention has been given to Soviet courts and the phenomenon of Soviet judicial mentality. The author depicts the priorities of post-Soviet transformation and comments on judicial reforms in Russia, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Georgia, Ukraine, Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan. The scope of analysis includes constitutional transformation, lustration efforts, police reform and certain legislative developments (mainly criminal law and criminal procedure). The focal point of the analysis is the impact of the path dependence factor on the post-Soviet transition of the countries of study. Commenting on the current situation in the Russian Federation, the author discusses the signs of re-birth of certain traditions and approaches of Soviet criminal law in modern Russia. The book also provides analysis of Vladimir Putin’s constitutional amendments that came into force in July of 2020. Ekaterina Mishina has asserted her right under Chapter 70 of the Civil Code of the RF, 2006, to be identified as Author of this work. UDC 347.97/.99(47+57) ISBN 978-5-903135-74-5 © Liberal Mission Foundation, 2020 © E. Mishina, 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE ________________________________________________________ 4 INTRODUCTION __________________________________________________ 7 PART I. -

Vladimir Putin

Vladimir Putin Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin (/ˈpuːtɪn/; Russian: Влади́мир Влади́мирович Пу́тин, IPA: [vɫɐ Vladimir Putin ˈdʲimʲɪr vɫɐˈdʲimʲɪrəvʲɪtɕ ˈputʲɪn] ( listen); born 7 October 1952) is a Russian politician and former intelligence officer serving as President of Russia since 2012, previously holding the position from 2000 until 2008.[3][4][5] He was Prime Minister of Russia from 1999 until the beginning of his first presidency in 2000, and again between presidencies from 2008 until 2012.[6] During his first term as Prime Minister, he served as Acting President of Russia due to the resignation of President Boris Yeltsin.[7] During his second term as Prime Minister, he was the chairman of the rulingUnited Russia party.[3] Putin was born in Leningrad in the Soviet Union. He studied law at Leningrad State University, graduating in 1975.[8] Putin was a KGB foreign intelligence officer for 16 years, rising to the rank of Lieutenant Colonel before resigning in 1991 to enter politics in Saint Petersburg. He moved to Moscow in 1996 and joined President Boris Yeltsin's administration, rising quickly through the ranks and becoming Acting President on 31 December 1999, when Yeltsin resigned. Putin won the 2000 presidential election by a 53% to 30% margin, thus avoiding a runoff with his Communist Party of the Russian Federation opponent, Gennady Zyuganov.[9] He was reelected president in 2004 with 72% of the vote. During his first presidency, the Russian economy grew for eight straight years, and GDP measured in purchasing power increased by 72%.[10][11] The growth was a result of the 2000s commodities boom, [12][13] high oil prices, and prudent economic and fiscal policies. -

Study Guide PS CP Comparative Politics

Study Guide PS_CP Comparative Politics Foreword Purpose and Structure This document is called a Study Guide. It is a written script to walk you through the topics within a study unit, called a Module, in your Kiron studies. It introduces the subjects in the module and links to the relevant parts in the online courses that you have to take in order to complete the module. It provides video lectures, written pieces, other kinds of enriching materials and suggested exercises from additional open educational resources to elaborate on the topics. The purpose of this document is to accompany you while you are studying the online courses in the module. It is not a replacement of any course or content within the modules, thus completing this material only helps you progressing in an easier way in your module. While you can share your thoughts and report errors on this material, your feedback and questions regarding the external contents should be addressed to the producers and owners of those materials. Kiron uses third-party content and thus the opinions presented do not necessarily represent those of Kiron Open Higher Education. Iconography Below are the meanings of the icons that are used in this document: General hints, suggestions and other things to check Video lesson or tutorial resource Book, web page or other written material resource Exercise or assessment resource Discussion point in Kiron Forum, Google Classroom or Google Hangouts Reference to the Kiron Campus or to a MOOC 1 Table of Contents Purpose and Structure 1 Iconography -

President Medvedev's Reform of the Mvd: a Step Towards Democratic Policing in Russia?

President Medvedev’s Reform Of The Mvd: A Step Towards Democratic Policing In Russia? by Bohdan Harasymiw Professor Emeritus of Political Science University of Calgary [email protected] ABSTRACT Brian D. Taylor’s groundbreaking study, State Building in Putin’s Russia: Policing and Coercion after Communism (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2011), demonstrates the critical importance of the development of democratic policing if Russia is to build the institutions and order which are essential in a democracy. It also shows that President Putin’s state-building policies, unfortunately, carried Russia in the opposite direction. In the final year of the term of office of his successor, Dmitry Medvedev, a new effort was made to reform the Ministry of Internal Affairs (MVD), responsible for the police, and its operations. The objective of the present paper is to assess whether this most recent reform effort was finally taking Russia away from the predatory and/or repressive models of policing into the democratic (protective) mould. Rule of law means nothing if a country’s police are themselves not bound by the rule of law. Using official Russian government sources (e.g., Rossiiskaia gazeta) as well as other newspaper and monographic accounts, including results of public opinion surveys, the paper assesses progress made in 2011 in the reform of Russian policing. History and bureaucratic inertia predict a pessimistic outcome to Medvedev’s policies. Russia’s situation is further complicated by universal trends, especially in Western democracies, where traditional patterns of policing, and police accountability, are coming increasingly into question, thus thoroughly muddling the whole notion of policing. -

Rural Development : Russian Style by PHAIBOON TARSAKOO : Policy and Strategy Expert 1

Rural Development : Russian Style BY PHAIBOON TARSAKOO : Policy and strategy Expert 1. Globalization 2. History Of Russia 3. Basici Faicts 4. Rural Development Aspects 5. Comprehensive Rural Development 6. Trends Rural Development : Russian Style 1. Globalization 2. History Of Russia Early Days An ancient empire, the cradle of three modern-day nations… This was Kievan Rus – a powerful East Slavic state dominated by the city of Kiev. Shaped in the 9th century it went on to flourish for the next 300 years. The empire is traditionally seen as the beginning of Russia and the ancestor of Belarus and Ukraine. From those ancient times comes a popular proverb “Your tongue will take you to Kiev”. If you’re wondering how or why a part of your body would transport you to a European capital, here’s the story. Legend has it that in 999 a Kiev resident called Nikita Shchekomyaka got lost in the far-away steppes and was caught by a militant nomadic tribe. Nikita’s tales of Kiev’s wealth and splendour impressed the tribe’s chief so much, he hooked Nikita by the tongue to his horse’s tail and went to wage war against Kiev. That’s how Nikita’s tongue took him home. But don’t panic if you hear the saying – you won’t share the unfortunate Nikita’s lot. Today, the proverb simply means you can always ask your way around. Back in those ancient times Russia it seems nearly became a Muslim country. The story goes that its ruler at the time, Prince Vladimir, wanted to replace paganism with a new religion. -

Russian Police and Citizens

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Repository@Hull - CRIS Internet Journal of Criminology © 2013 ISSN 2045-6743 (Online) Russian Police and Transition to Democracy: Lessons from One Empirical Study By Margarita Zernova1 Abstract: The paper discusses public experiences of policing in today’s Russia, public attitudes towards police resulting from such experiences and wider social implications of those attitudes. At the basis of the discussion is an empirical study which has been carried out by the author. The study has found abundant evidence of distrust towards – and fear of – police by contemporary Russians. It is argued that the corrupt, brutal and unaccountable police who lack legitimacy in the eyes of citizens trigger public responses that may help to deepen social inequalities, subvert the process of establishing the rule of law and impede the Russian transition to democracy. Moreover, if citizens view the police as illegitimate – indeed, believe that the very state agency designed to protect them actually presents threats to their security – the legitimacy of the entire state structure is at risk. 1 Lecturer in Criminology, University of Hull, [email protected] www.internetjournalofcriminology.com 1 Internet Journal of Criminology © 2013 ISSN 2045-6743 (Online) Introduction To various degrees police legitimacy is a problem in every society, however it is particularly acute in societies undergoing change and experiencing rising social tensions (Weitzer 1995, Mishler and Rose 1998, Goldsmith 2005). This paper focuses on the case of Russia as an empirical study and uses narratives derived from in-depth interviews with members of the public who have had encounters with the police in the post-Soviet period to demonstrate the lack of police legitimacy. -

Volume. 38, No. 2, April 2017

ISSN 1010-9536 GLOBALISATION AND ITS IMPACT ON STRATEGIC PARTNERSHIPS 77 Does Distance Matter for Bangladesh’s Exports? Mahfuz Kabir 93 Bangladesh-India Water Negotiations: Challenges and Way Forward Shanjida Shahab Uddin Syeda Tanzia Sultana 119 Bangladesh-China Relations: From Closer Comprehensive Partnership to Strategic Partnership Samia Zaman Roksana Islam Sujana 139 Indian Ocean Rim Association (IORA) at 20: An Assessment Moutusi Islam 163 Russia’s Revival in Global Aairs: Will there Be New Conicts with the West? Mahbubur Rashid Bhuiyan Volume 38 Number 2 2017 I Contacts Designation Telephone (Oce) E-mail Chairman, Board of Governors 88-02-9347914 [email protected] Director General 88-02-8312609 [email protected] Research Director-1 88-02-9331977 [email protected] Research Director-2 88-02-8360198 [email protected] VOLUME 38 NUMBER 2 APRIL 2017 Disclaimer: This is a peer reviewed journal. The views and opinions expressed in this Journal are solely of the authors and do not reect the ocial policy or position of Bangladesh Institute of International and Strategic Studies (BIISS). Bangladesh Institute of International and Strategic Studies (BIISS) Dhaka Chief Editor A K M Abdur Rahman Editor Sheikh Masud Ahmed Associate Editor Shaheen Afroze Assistant Editors Mohammad Jasim Uddin Md. Muhibbur Rahman A. S. M. Tarek Hassan Semul BIISS Journal (ISSN 1010-9536) is published quarterly by the Bangladesh Institute of International and Strategic Studies (BIISS), Dhaka, in January, April, July and October. The journal provides a forum for debate and discussion on international aairs, security and development issues in national, regional and global perspectives. Original contributions (along with an abstract of 200-300 words) not published elsewhere may be submitted to the Chief Editor (Director General, BIISS)/Editor in duplicate, typed double-spaced, normally within about 6000 words. -

Challenge Europe

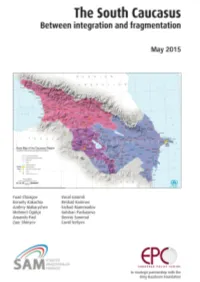

The South Caucasus Between integration and fragmentation Fuad Chiragov Vusal Gasimli Kornely Kakachia Reshad Karimov Andrey Makarychev Farhad Mammadov Mehmet Ögütçü Gulshan Pashayeva Amanda Paul Dennis Sammut Zaur Shiriyev Cavid Veliyev The views expressed, and terminology used in these papers are those of the authors and do not represent those of the EPC or SAM. May 2015 ISSN-1783-2462 Table of contents About the authors 5 Abbreviations 6 Introduction 9 Europeanisation and Georgian foreign policy 11 Kornely Kakachia Russia's policies in the South Caucacus after the crisis in Ukraine: the vulnerabilities of realism 19 Andrey Makarychev Azerbaijan's foreign policy – A new paradigm of careful pragmatism 29 Farhad Mammadov Security challenges and conflict resolution efforts in the South Caucasus 37 Gulshan Pashayeva Armenia – Stuck between a rock and a hard place 45 Dennis Sammut Iran's policy in the South Caucasus – Between pragmatism and realpolitik 53 Amanda Paul Trade, economic and energy cooperation: challenges for a fragmented region 61 Vusal Gasimli NATO's South Caucasus paradigm: beyond 2014 67 Zaur Shiriyev The EU and the South Caucasus – Time for a stocktake 77 Amanda Paul Turkey's role in the South Caucasus: between fragmentation and integration 85 Cavid Veliyev 3 Policies from afar: the US options towards greater regional unity in the South Caucasus 95 Fuad Chiragov and Reshad Karimov China in the South Caucasus: not a critical partnership but still needed 103 Mehmet Ögütçü 4 About the authors Fuad Chiragov, Research Fellow, -

Homicide in Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus 29 Alexandra V

Homicide in Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus 29 Alexandra V. Lysova, Nikolay G. Shchitov, and William Alex Pridemore cal and economic stability in these nations over Introduction the last several years compared to the mid-1990s, homicide rates have not decreased as drastically This chapter discusses homicide in Russia, as they increased during that earlier period. Ukraine, and Belarus. Given its greater popula- Second, given the sweeping scale of socio- tion, geographic size, geopolitical presence, and economic and political change in the 1990s in more readily available data, we focus on Russia, Russia and Ukraine, and to a lesser extent though where possible we also provide informa- Belarus, these nations may serve as natural tion about Ukraine and Belarus. For a number of experiments for testing various sociological and reasons, these post-Soviet countries deserve spe- criminological theories, especially those related cial attention when considering homicide in to anomie, as potential explanations for the Europe. First, the social, economic, and political increase in homicide rates (Kim & Pridemore, turmoil experienced by many former Soviet 2005; Pridemore, Chamlin, & Cochran, 2007; countries following the collapse of the Soviet Pridemore & Kim, 2006). Recent research also Union was accompanied by a sharp rise in all- revealed several other factors that help to explain cause mortality. In particular, deaths from homi- the variation of homicide rates in these coun- cide increased sharply in many of these nations. tries, including specific historical conditions, In 2003, the Russian homicide rate of over hazardous alcohol consumption, social structural 21/100,000 residents annually (MVD RF, 2010) factors like poverty and family instability, and was the highest in Europe (World Health individual-level factors like education and mar- Organization, 2010a) and one of the highest in riage (Andrienko, 2001; Chervyakov, Shkolnikov, the world (Krug et al., 2002). -

Humanities in the 21St Century: Scientific Problems and Searching for Effective Humanist Technologies

Humanities in the 21st century: scientific problems and searching for effective humanist technologies Research articles HUMANITIES IN THE 21ST CENTURY: SCIENTIFIC PROBLEMS AND SEARCHING FOR EFFECTIVE HUMANIST TECHNOLOGIES Research articles B&M Publishing San Francisco, California, USA SCIENTIFIC ENQUIRY IN THE CONTEMPORARY WORLD: THEORETICAL BASIСS AND INNOVATIVE APPROACHLOBAL C L SCIENCE B&M Publishing Research and Publishing Center «Colloquium» HUMANITIES IN THE 21ST CENTURY: SCIENTIFIC PROBLEMS AND SEARCHING FOR EFFECTIVE HUMANIST TECHNOLOGIES Science editor: E. Murzina Copyright © 2016 ISBN-10:1-941655-37-8 by Research and Publishing Center ISBN-13:978-1-941655-37-5 «Colloquium» DOI: 10.15350/L_21 All rights reserved. Published by B&M Publishing. San Francisco, California 2 CONTENTS CONTENTS HISTORICAL SCIENCES The history of investigations of Karakalpakstan animal world in the years 5 of independence U. Khujaniyazov Ukrainian nationalism dynamics in the first half of the XIX century 9 S. Mozgovoi For the study of the history and culture of the Turkic and Finno-Ugric peoples 14 of Russia in the society of archeology, history and ethnography (1878-1930) M. Khabibullin, I. Valiullin, R. Batyrshin ART The portrait gallery in the mural painting of the Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra's 17 Dormition Cathedral in the first half of XIX century M. Bardik PHILOLOGY Using the elements of spoken language in the language of drama-fairy play 24 «Forest song» of Lesya Ukrainka T. Panchenko Visualization of the art text 28 G. Popova Anti-war trеnd of the play «Mother Courage and her children» 36 by Bertolt Brecht N. Chernysh Semantic structure of the concept GLOBALIZATION 40 A.