Partnerships and Creation: a Brief History Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Evolution of the Clarinet and Its Effect on Compositions Written for the Instrument

Columbus State University CSU ePress Theses and Dissertations Student Publications 5-2016 The Evolution of the Clarinet and Its Effect on Compositions Written for the Instrument Victoria A. Hargrove Follow this and additional works at: https://csuepress.columbusstate.edu/theses_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Hargrove, Victoria A., "The Evolution of the Clarinet and Its Effect on Compositions Written for the Instrument" (2016). Theses and Dissertations. 236. https://csuepress.columbusstate.edu/theses_dissertations/236 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Publications at CSU ePress. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CSU ePress. THE EVOLUTION OF THE CLARINET AND ITS EFFECT ON COMPOSITIONS WRITTEN FOR THE INSTRUMENT Victoria A. Hargrove COLUMBUS STATE UNIVERSITY THE EVOLUTION OF THE CLARINET AND ITS EFFECT ON COMPOSITIONS WRITTEN FOR THE INSTRUMENT A THESIS SUBMITTED TO HONORS COLLEGE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE HONORS IN THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF MUSIC SCHWOB SCHOOL OF MUSIC COLLEGE OF THE ARTS BY VICTORIA A. HARGROVE THE EVOLUTION OF THE CLARINET AND ITS EFFECT ON COMPOSITIONS WRITTEN FOR THE INSTRUMENT By Victoria A. Hargrove A Thesis Submitted to the HONORS COLLEGE In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Honors in the Degree of BACHELOR OF MUSIC PERFORMANCE COLLEGE OF THE ARTS Thesis Advisor Date ^ It, Committee Member U/oCWV arcJc\jL uu? t Date Dr. Susan Tomkiewicz A Honors College Dean ABSTRACT The purpose of this lecture recital was to reflect upon the rapid mechanical progression of the clarinet, a fairly new instrument to the musical world and how these quick changes effected the way composers were writing music for the instrument. -

2019 Preview Notes • Week Two • Persons Auditorium

2019 Preview Notes • Week Two • Persons Auditorium Saturday, July 20 at 8:00pm Flute Quartet in D Major, K. 285 (1777-78) Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Born January 27, 1756 • Died December 5, 1791 Duration: approx. 15 minutes Last Marlboro performance: 2011 When Mozart was just a few years younger than the junior participants in this group, he travelled throughout Europe with his mother in search of employment. While in Mannheim on his way to Paris, he met a Dutch merchant named Willem van Britten Dejong who happened to be an amateur flute player. Dejong, who had made his fortune in India, was happy to commission three concertos and three quartets for his instrument. Mozart, who needed the funds, was happy to accept. However, he only completed the quartets and two concertos (one a transcription of a previously-composed oboe concerto) by the time he left Mannheim. What he did write, though, charmingly showcases the flute. In this quartet, that instrument takes the lead throughout a buoyant Allegro beginning, a delicate Adagio accompanied by sparkling plucking from the strings, and a boisterous but well-balanced Rondo conclusion. Participants: Giorgio Consolati, flute; Hiroko Yajima, violin; Jordan Bak, viola; Alexander Hersh, cello Octet (2004) Jörg Widmann Born June 19, 1973 • In residence 2008, 2019 Duration: approx. 30 minutes Marlboro Premiere Though Widmann’s Octet features frequent microtones, he admits that the piece is “almost throughout, a tonal piece,” which was “risky to write in 2004.” The instrumentation suggests a clear connection to Schubert’s genre-making octet, and the piece’s central third movement, which is titled Lied ohne Worte, is a plangent nod to the composer who wrote so many Lieder over the course of his short life. -

PROGRAM NOTES Wolfgang Mozart Clarinet Concerto in a Major, K

PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher Wolfgang Mozart Born January 27, 1756, Salzburg, Austria. Died December 5, 1791, Vienna, Austria. Clarinet Concerto in A Major, K. 622 Mozart composed this concerto between the end of September and mid-November 1791, and it apparently was performed in Vienna shortly afterwards. The orchestra consists of two flutes, two bassoons, two horns, and strings. Performance time is approximately twenty-nine minutes. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s first performance of Mozart’s Clarinet Concerto was given at the Ravinia Festival on July 25, 1957, with Reginald Kell as soloist and Georg Solti conducting. The Orchestra’s first subscription concert performance was given at Orchestra Hall on May 2, 1963, with Clark Brody as soloist and Walter Hendl conducting. Our most recent subscription concert performances were given on October 11 and 12, 1991, with Larry Combs as soloist and Sir Georg Solti conducting. The Orchestra most recently performed this concerto at the Ravinia Festival on July 15, 2001, with Larry Combs as soloist and Sir Andrew Davis conducting. This concerto is the last important work Mozart finished before his death. He recorded it in his personal catalog without a date, right after The Magic Flute and La clemenza di Tito. The only later entry is the little Masonic Cantata, dated November 15, 1791. The Requiem, as we know, didn’t make it into the list. For decades the history of the Requiem was full of ambiguity, while that of the Clarinet Concerto seemed quite clear. But in recent years, as we learned more about the unfinished Requiem, questions about the concerto began to emerge. -

Sonata for Clarinet Choir Donald S

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 1962 Sonata for Clarinet Choir Donald S. Lewellen Eastern Illinois University Recommended Citation Lewellen, Donald S., "Sonata for Clarinet Choir" (1962). Masters Theses. 4371. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/4371 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. -SONATA POR CLARINET CHOIR A PAPER PRESENTED TO THE FACULTY OF TILE DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC EASTERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF TIIB REQUIREMENTS FOR IBE DEGREE MASTER OF SCIENCE IN EDUCATION DONALDS. LEWELLEN '""'."'.···-,-·. JULY, 1962' TABLE OF CONTENTS :le Page • • • • • • • . • .. • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • i ile of Contents . .. ii iface ••.•....•...•........••....... •· ...•......•.•...• iii ::tion I ! Orchestra and Band ································· 1 lrinet Choir New Concept of Sound •••••••••••••••••• 2 3.rinet Choir Medium of Musical Expression . .. 2 arinet Choir Instrumentation . 3 ction II nata for Clarinet Choir - Analysis . .. 6 mmary • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 8 bliography ••••.•••••••••••••••••••••••.•••••••••••••• 10 PREFACE The available literature for clarinet choir is quite limited, and much of this literature is an arrangement of orchestral music. -

The Recently Rediscovered Works of Heinrich Baermann by Madelyn Moore Submitted to the Graduate Degree Program in Music And

The Recently Rediscovered Works of Heinrich Baermann By Madelyn Moore Submitted to the graduate degree program in Music and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Music. ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. Eric Stomberg ________________________________ Dr. Robert Walzel ________________________________ Dr. Paul Popiel ________________________________ Dr. David Alan Street ________________________________ Dr. Marylee Southard Date Defended: April 1, 2014 The Dissertation Committee for Madelyn Moore certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: The Recently Rediscovered Works of Heinrich Baermann ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. Eric Stomberg Date approved: April 22, 2014 ii Abstract While Heinrich Baermann was one of the most famous virtuosi of the first half of the nineteenth century and is one of the most revered clarinetists of all time, it is not well known that Baermann often performed works of his own composition. He composed nearly 40 pieces of varied instrumentation, most of which, unfortunately, were either never published or are long out of print. Baermann’s style of playing has influenced virtually all clarinetists since his life, and his virtuosity inspired many composers. Indeed, Carl Maria von Weber wrote two concerti, a concertino, a set of theme and variations, and a quintet all for Baermann. This document explores Baermann’s relationships with Weber and other composers, and the influence that he had on performance practice. Furthermore, this paper discusses three of Baermann’s compositions, critical editions of which were made during the process of this research. The ultimate goal of this project is to expand our collective knowledge of Heinrich Baermann and the influence that he had on performance practice by examining his life and three of the works that he wrote for himself. -

The Inspiration Behind Compositions for Clarinetist Frederick Thurston

THE INSPIRATION BEHIND COMPOSITIONS FOR CLARINETIST FREDERICK THURSTON Aileen Marie Razey, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 201 8 APPROVED: Kimberly Cole Luevano, Major Professor Warren Henry, Committee Member John Scott, Committee Member John Holt, Chair of the Division of Instrumental Studies Benjamin Brand, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music John Richmond, Dean of the College of Music Victor Prybutok, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Razey, Aileen Marie. The Inspiration behind Compositions for Clarinetist Frederick Thurston. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), August 2018, 86 pp., references, 51 titles. Frederick Thurston was a prominent British clarinet performer and teacher in the first half of the 20th century. Due to the brevity of his life and the impact of two world wars, Thurston’s legacy is often overlooked among clarinetists in the United States. Thurston’s playing inspired 19 composers to write 22 solo and chamber works for him, none of which he personally commissioned. The purpose of this document is to provide a comprehensive biography of Thurston’s career as clarinet performer and teacher with a complete bibliography of compositions written for him. With biographical knowledge and access to the few extant recordings of Thurston’s playing, clarinetists may gain a fuller understanding of Thurston’s ideal clarinet sound and musical ideas. These resources are necessary in order to recognize the qualities about his playing that inspired composers to write for him and to perform these works with the composers’ inspiration in mind. Despite the vast list of works written for and dedicated to Thurston, clarinet players in the United States are not familiar with many of these works, and available resources do not include a complete listing. -

Boosey & Hawkes

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Howell, Jocelyn (2016). Boosey & Hawkes: The rise and fall of a wind instrument manufacturing empire. (Unpublished Doctoral thesis, City, University of London) This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/16081/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] Boosey & Hawkes: The Rise and Fall of a Wind Instrument Manufacturing Empire Jocelyn Howell PhD in Music City University London, Department of Music July 2016 Volume 1 of 2 1 Table of Contents Table of Contents .................................................................................................................................... 2 Table of Figures...................................................................................................................................... -

Kimberly Cole Luevano, DMA

Kimberly Cole Luevano, DMA College of Music 1809 Goshawk Lane University of North Texas Corinth, TX 76210 Denton, TX 76203 734.678.9898 940.565.4096 [email protected] [email protected] Present Appointments University of North Texas, Denton, TX. Professor 2018-present Associate Professor 2012-2018 Assistant Professor 2011-2012 Responsibilities include: • Teaching Applied Clarinet lessons. • Teaching Doctoral Clarinet Literature course (MUAG 6360). • Teaching pedagogy courses as needed (MUAG 4360/5360). • Serving on graduate student recital and exam committees. • Advising doctoral students in development and completion of dissertation work. • Assisting in coordination of instruction of clarinet concentration lessons, clarinet secondary lessons, clarinet minor lessons, and all clarinet jury examinations. • Assisting in oversight of graduate Teaching Fellow position. • Collaborating with faculty colleagues in their performances. • Assisting in instruction of woodwinds methods classes as needed. • Coaching student chamber ensembles as needed. • Recruitment and development of the clarinet studio. • Listening to ensemble auditions for placement of clarinetists in ensembles. Director: UNT ClarEssentials Summer Workshop 2011- 2018 • Artistic direction, administration, and oversight of all aspects of the 5-day on- campus event for high school clarinetists. Haven Trio (Lindsay Kesselman, soprano; Midori Koga, piano). 2012-present TrioPolis Trio (Felix Olschofka, violin; Anatolia Ioannides, piano) 2016-present Artist Clinician: Henri Selmer-Paris 2015 – present Artist Clinician: Conn-Selmer USA 2015 – present Artist Clinician: The D’Addario Company 2013- present Education Doctor of Musical Arts degree in Clarinet Performance, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI. 1996 Master of Music degree in Clarinet Performance, Music History concentration, Michigan State University. 1994 Postgraduate Study, L’Ecole Normale de Musique de Paris, Paris, France. -

Repertoire List

APPROVED REPERTOIRE FOR 2022 COMPETITION: Please choose your repertoire from the approved selections below. Repertoire substitution requests will be considered by the Charlotte Symphony on an individual case-by-case basis. The deadline for all repertoire approvals is September 15, 2021. Please email [email protected] with any questions. VIOLIN VIOLINCELLO J.S. BACH Violin Concerto No. 1 in A Minor BOCCHERINI All cello concerti Violin Concerto No. 2 in E Major DVORAK Cello Concerto in B Minor BEETHOVEN Romance No. 1 in G Major Romance No. 2 in F Major HAYDN Cello Concerto No. 1 in C Major Cello Concerto No. 2 in D Major BRUCH Violin Concerto No. 1 in G Minor LALO Cello Concerto in D Minor HAYDN Violin Concerto in C Major Violin Concerto in G Major SAINT-SAENS Cello Concerto No. 1 in A Minor Cello Concerto No. 2 in D Minor LALO Symphonie Espagnole for Violin SCHUMANN Cello Concerto in A Minor MENDELSSOHN Violin Concerto in E Minor DOUBLE BASS MONTI Czárdás BOTTESINI Double Bass Concerto No. 2in B Minor MOZART Violin Concerti Nos. 1 – 5 DITTERSDORF Double Bass Concerto in E Major PROKOFIEV Violin Concerto No. 2 in G Minor DRAGONETTI All double bass concerti SAINT-SAENS Introduction & Rondo Capriccioso KOUSSEVITSKY Double Bass Concerto in F# Minor Violin Concerto No. 3 in B Minor HARP SCHUBERT Rondo in A Major for Violin and Strings DEBUSSY Danses Sacrée et Profane (in entirety) SIBELIUS Violin Concerto in D Minor DITTERSDORF Harp Concerto in A Major VIVALDI The Four Seasons HANDEL Harp Concerto in Bb Major, Op. -

Why Do Singers Sing in the Way They

Why do singers sing in the way they do? Why, for example, is western classical singing so different from pop singing? How is it that Freddie Mercury and Montserrat Caballe could sing together? These are the kinds of questions which John Potter, a singer of international repute and himself the master of many styles, poses in this fascinating book, which is effectively a history of singing style. He finds the reasons to be primarily ideological rather than specifically musical. His book identifies particular historical 'moments of change' in singing technique and style, and relates these to a three-stage theory of style based on the relationship of singing to text. There is a substantial section on meaning in singing, and a discussion of how the transmission of meaning is enabled or inhibited by different varieties of style or technique. VOCAL AUTHORITY VOCAL AUTHORITY Singing style and ideology JOHN POTTER CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS PUBLISHED BY THE PRESS SYNDICATE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge CB2 IRP, United Kingdom CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 2RU, United Kingdom 40 West 20th Street, New York, NY 10011-4211, USA 10 Stamford Road, Oakleigh, Melbourne 3166, Australia © Cambridge University Press 1998 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 1998 Typeset in Baskerville 11 /12^ pt [ c E] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library library of Congress cataloguing in publication data Potter, John, tenor. -

O Ensino Da Clarineta Em Nível Superior: Materiais Didáticos E O Desenvolvimento Técnico-Interpretativo Do Clarinetista

Universidade Federal da Paraíba Centro de Comunicação, Turismo e Artes Programa de Pós-Graduação em Música Mestrado em Música O Ensino da Clarineta em Nível Superior: materiais didáticos e o desenvolvimento técnico-interpretativo do clarinetista Eduardo Filippe de Lima João Pessoa Março de 2019 Universidade Federal da Paraíba Centro de Comunicação, Turismo e Artes Programa de Pós-Graduação em Música Mestrado em Música O Ensino da Clarineta em Nível Superior: materiais didáticos e o desenvolvimento técnico-interpretativo do clarinetista Eduardo Filippe de Lima Orientador: Dr. Fábio Henrique Gomes Ribeiro Trabalho apresentado ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Música da Universidade Federal da Paraíba como requisito para a obtenção do título de Mestre em Música, área de concentração em Educação Musical. João Pessoa Março de 2019 Catalogação na publicação Seção de Catalogação e Classificação L732e Lima, Eduardo Filippe de. O Ensino da Clarineta em Nível Superior: materiais didáticos e o desenvolvimento técnico-interpretativo do clarinetista / Eduardo Filippe de Lima. - João Pessoa, 2019. 111f. : il. Orientação: Fábio Henrique Gomes Ribeiro. Dissertação (Mestrado) - UFPB/CCTA. 1. Ensino de instrumento musical. 2. Ensino da clarineta em nível superior. 3. Materiais didáticos para clarineta. 4. Desenvolvimento técnico-interpretativo do clarinet. I. Ribeiro, Fábio Henrique Gomes. II. Título. UFPB/BC 3 AGRADECIMENTOS Gostaria de agradecer imensamente a todos que contribuíram de maneira direta e indireta para a conclusão desse curso de mestrado, o qual me trouxe um profundo amadurecimento pessoal e profissional, e que simboliza o encerramento de mais um ciclo na minha carreira musical. À minha família, que sempre me deu apoio e o suporte necessário para continuar com todos os meus projetos, incluindo esse curso; Ao meu orientador, prof. -

Proposal to Create the Doctor of Musical Arts Degree Program

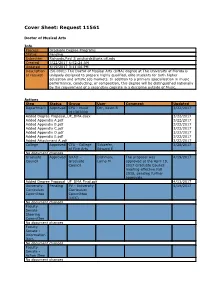

Cover Sheet: Request 11561 Doctor of Musical Arts Info Process Graduate Degree Programs Status Pending Submitter Richards,Paul S [email protected] Created 3/22/2017 6:52:24 AM Updated 4/19/2017 3:11:06 PM Description (50.0901) The Doctor of Musical Arts (DMA) degree at The University of Florida is of request uniquely designed to prepare highly qualified, elite students for both higher education and artistic job markets. In addition to a primary specialization in music performance, conducting, or composition, this degree will be distinguished nationally by the requirement of a secondary cognate in a discipline outside of Music. Actions Step Status Group User Comment Updated Department Approved CFA - Music Orr, Kevin R 3/22/2017 011303000 Added Degree Proposal_UF_DMA.docx 3/22/2017 Added Appendix A.pdf 3/22/2017 Added Appendix B.pdf 3/22/2017 Added Appendix C.pdf 3/22/2017 Added Appendix D.pdf 3/22/2017 Added Appendix E.pdf 3/22/2017 Added Attachment A.pdf 3/22/2017 College Approved CFA - College Schaefer, 3/28/2017 of Fine Arts Edward E No document changes Graduate Approved GRAD - Dishman, The proposal was 4/19/2017 Council Graduate Lorna M approved at the April 19, Council 2017 Graduate Council meeting effective Fall 2018, pending further approvals. Added Degree Proposal_UF_DMA Final.pdf 4/13/2017 University Pending PV - University 4/19/2017 Curriculum Curriculum Committee Committee (UCC) No document changes Faculty Senate Steering Committee No document changes Faculty Senate - Information Item No document changes Faculty Senate -