Of the World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Technical Specification Summary

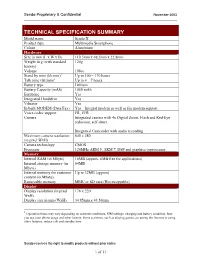

Sendo Proprietary & Confidential November 2003 ____________________________________________________________________________________ TECHNICAL SPECIFICATION SUMMARY Model name Sendo X Product type Multimedia Smartphone Colour Aluminium Hardware Size in mm (L x W x B) 110.5mm x 48.5mm x 22.8mm Weight in g (with standard 120g battery) Volume 108cc Stand by time (hh:mm)1 Up to 100 – 170 hours Talk time (hh:mm)1 Up to 4 – 7 hours Battery type Lithium Battery Capacity (mAh) 1050 mAh Earphone Yes Integrated Handsfree Yes Vibrator Yes In built MODEM (Data/Fax) Yes – Integral modem as well as fax modem support Voice codec support FR, EFR Camera Integrated camera with 4x Digital Zoom, Flash and Red-Eye reduction, self-timer. Integrated Camcorder with audio recording Maximum camera resolution 640 x 480 (in pixel WxH) Camera technology CMOS Processor 120MHz ARM 9, ARM 7, DSP and graphics coprocessor Memory Internal RAM (in Mbyte) 16MB (approx. 6MB free for applications) Internal storage memory (in 64MB Mbyte) Internal memory for customer Up to 32MB (approx) content (in Mbyte) Removable memory MMC or SD card (Hot swappable) Display Display resolution (in pixel 176 x 220 WxH) Display size in mm (WxH) 34.85mm x 43.56mm 1 Operation times may vary depending on network conditions, SIM settings, charging and battery condition, how you use your phone usage and other factors. Some activities, such as playing games, accessing the Internet or using other features, reduce talk and standby time. Sendo reserves the right to modify products without prior notice -

Dimetra X Core

DIMETRA X CORE FOLHA DE DADOS | DIMETRA X CORE EM BREVE, TANTO OS ÓRGÃOS GOVERNAMENTAIS E DE SEGURANÇA PÚBLICA COMO AS GRANDES EMPRESAS CONTARÃO COM TECNOLOGIA DE BANDA LARGA SEM FIO. E ENQUANTO VOCÊ NÃO SABE QUANDO A MUDANÇA VAI ACONTECER, VOCÊ JÁ PODE ESTAR PRONTO PARA ELA COM O DIMETRA™ X CORE. PROJETADO PARA POTENCIALIZAR AO MÁXIMO A SUA REDE DIMETRA ATUAL, ENQUANTO VOCÊ SE PREPARA PARA AS CAPACIDADES ADICIONAIS QUE A TECNOLOGIA DE BANDA LARGA MÓVEL PODERÁ OFERECER. DIMETRA X CORE PRONTOS PARA O FUTURO, HOJE Com um núcleo definido por software, segurança cibernética aprimorada PRINCIPAIS CARACTERÍSTICAS e interfaces inteligentes, DIMETRA X Core foi projetado para um • Arquitetura avançada máximo desempenho em longo prazo, proporcionando as comunicações de missão crítica que você necessita para os próximos 15 anos ou mais. • Núcleo definido por software Ao substituir sua rede central atual por DIMETRA X Core, você estará • Investimento protegido na rede de acesso de rádio fazendo um investimento verdadeiramente rentável a fim de otimizar e estender a vida útil de sua rede de acesso de rádio DIMETRA. • Totalmente escalável de 1 para 5.000 sites ou mais • Conjunto de recursos abrangente Assim como a tecnologia evolui, o seu sistema DIMETRA também irá evoluir. Ele apresenta uma arquitetura completamente escalável que • Núcleo virtualizado e consolidado permite ampliar o sistema de um site para 5.000 ou mais. E, à medida • Flexibilidade de capacidade que você precisar, pode ir adicionando facilmente novos usuários e capacidades através de licenças de software. • Flexibilidade de recursos • Preços escaláveis DIMETRA X Core consome menos energia e diminui o Custo Total de Propriedade a longo prazo para sua organização. -

The Next Frontier for Openness: Wireless Communications

The Next Frontier for Openness: Wireless Communications Early Discussion Draft Eli M. Noam Professor of Finance and Economics, and Director, Columbia Institute for Tele-Information, Columbia University Paper for the 2001 Telecommunications Policy Research Conference Alexandria, Virginia September 25, 2001 Abstract For wireless communications, the FCC has fostered competition rather than openness. This has permitted the emergence of vertically integrated end-to-end providers, creating problems of reduced hardware innovation, software applications, user choice, and content access. To deal with these emerging issues and create multi-level forms of competition, one policy is likely to suffice: a Carterfone for wireless, coupled with more unlicensed spectrum. The Wireless Policy Mess Openness is more than competition. Competition means the ability of companies to contest each other and to seek customers’ business. This can result in efficiency and enhanced consumer welfare. But it can also result in a competition among bundled product packages instead of competition on a product-by-product basis. Openness, on the other hand, means the ability of competitors to access consumers directly rather through their own rivals. This is particularly an issue in network industries, and has been a constant theme of regulatory battles for over a century. In telecommunications, product and service markets were closed to competitors for a long time. For example, rival equipment makers existed domestically and internationally but could not reach customers of AT&T'’ network. Telephone networks were opened first to customer equipment. Then it was long distance and international service. Then, network equipment. Then, local telecommunications. It has now been extended to internet service over cable TV networks. -

Tugas Bahasa Inggris Ii

TUGAS BAHASA INGGRIS II Mobile Phone Oleh : Muhammad Zainul Abidin (103112702650017) FAKULTAS TEKNOLOGI KOMUNIKASI DAN INFORMATIKA TELEKOMUNIKASI UNIVERSITAS NASIONAL 2012 Mobile phone A mobile phone (also known as a cellular phone, cell phone and a hand phone) is a device that can make and receive telephone calls over a radio linkwhilst moving around a wide geographic area. It does so by connecting to a cellular network provided by a mobile phone operator, allowing access to thepublic telephone network. By contrast, a cordless telephone is used only within the short range of a single, private base station. In addition to telephony, modern mobile phones also support a wide variety of other services such as text messaging, MMS, email, Internet access, short-range wireless communications (infrared, Bluetooth), business applications, gaming and photography. Mobile phones that offer these and more general computing capabilities are referred to as smartphones. The first hand-held mobile phone was demonstrated by Dr Martin Cooper of Motorola in 1973, using a handset weighing around 1 kg.In 1983, the DynaTAC 8000x was the first to be commercially available. In the twenty years from 1990 to 2011, worldwide mobile phone subscriptions grew from 12.4 million to over 5.6 billion, penetrating the developing economies and reaching the bottom of the economic pyramid History Radiophones have a long and varied history going back to Reginald Fessenden's invention and shore-to-ship demonstration of radio telephony, through theSecond World War with military use of radio telephony links and civil services in the 1950s. The first mobile telephone call made from a car occurred in St. -

Primary & Secondary Sources

Primary & Secondary Sources Brands & Products Agencies & Clients Media & Content Influencers & Licensees Organizations & Associations Government & Education Research & Data Multicultural Media Forecast 2019: Primary & Secondary Sources COPYRIGHT U.S. Multicultural Media Forecast 2019 Exclusive market research & strategic intelligence from PQ Media – Intelligent data for smarter business decisions In partnership with the Alliance for Inclusive and Multicultural Marketing at the Association of National Advertisers Co-authored at PQM by: Patrick Quinn – President & CEO Leo Kivijarv, PhD – EVP & Research Director Editorial Support at AIMM by: Bill Duggan – Group Executive Vice President, ANA Claudine Waite – Director, Content Marketing, Committees & Conferences, ANA Carlos Santiago – President & Chief Strategist, Santiago Solutions Group Except by express prior written permission from PQ Media LLC or the Association of National Advertisers, no part of this work may be copied or publicly distributed, displayed or disseminated by any means of publication or communication now known or developed hereafter, including in or by any: (i) directory or compilation or other printed publication; (ii) information storage or retrieval system; (iii) electronic device, including any analog or digital visual or audiovisual device or product. PQ Media and the Alliance for Inclusive and Multicultural Marketing at the Association of National Advertisers will protect and defend their copyright and all their other rights in this publication, including under the laws of copyright, misappropriation, trade secrets and unfair competition. All information and data contained in this report is obtained by PQ Media from sources that PQ Media believes to be accurate and reliable. However, errors and omissions in this report may result from human error and malfunctions in electronic conversion and transmission of textual and numeric data. -

Moto E6 Plus Ii

Guia de usuário i © 2019 Motorola Mobility LLC. Todos os direitos reservados. MOTOROLA, o logotipo M estilizado, MOTO e a família de marcas MOTO são marcas comerciais ou registradas da Motorola Trademark Holdings, LLC. LENOVO é uma marca comercial da Lenovo. Google, Android, Google Play e outras marcas são marcas comerciais da Google LLC. O logotipo microSD é uma marca comercial da SD-3C, LLC. Todos os outros nomes de produtos ou serviços pertencem aos seus respectivos proprietários. Alguns recursos, serviços e apps dependem da rede e podem não estar disponíveis em todas as áreas. Termos, condições e/ou taxas adicionais podem ser aplicáveis. Entre em contato com seu provedor de serviço para obter mais detalhes. Todos os recursos, funcionalidades e outras especificações de produto, bem como as informações deste conteúdo de ajuda, baseiam-se nas informações mais recentes disponíveis e consideradas precisas no momento do lançamento. A Motorola se reserva o direito de alterar ou modificar quaisquer informações ou especificações sem notificação prévia ou obrigação. Algumas imagens no conteúdo de ajuda são apenas exemplos. Você também pode visualizar essa ajuda no telefone, em: Configurações > Ajuda . Moto E6 Plus ii Conteúdo Configurar o telefone 1 Diagrama de hardware 1 Insira e remova os cartões SIM e SD 2 Gerenciamento do dual SIM 5 Adicionar ou remover contas 6 Configurar correio de voz 7 Configurar e-mail 8 Deixar o telefone com a sua cara 10 Configurações de acessibilidade 11 Assistência visual 11 Assistência auditiva 13 Assistência à -

Moto G7 Play Iii

Guia de usuário © 2021 Motorola Mobility LLC. Todos os direitos reservados. MOTOROLA, o logotipo M estilizado, MOTO e a família de marcas MOTO são marcas comerciais ou registradas da Motorola Trademark Holdings, LLC. LENOVO é uma marca comercial da Lenovo. Google, Android, Google Play e outras marcas são marcas comerciais da Google LLC. O logotipo microSD é uma marca comercial da SD-3C, LLC. Todos os demais nomes de produtos ou serviços são de propriedade de seus respectivos proprietários. Alguns recursos, serviços e apps dependem da rede e podem não estar disponíveis em todas as áreas. Termos, condições e/ou taxas adicionais podem ser aplicáveis. Entre em contato com seu provedor de serviço para obter mais detalhes. Todos os recursos, funcionalidades e outras especificações de produto, bem como as informações deste conteúdo de ajuda, baseiam-se nas informações mais recentes disponíveis e consideradas precisas no momento do lançamento. A Motorola se reserva o direito de alterar ou modificar quaisquer informações ou especificações sem notificação prévia ou obrigação. Algumas imagens no conteúdo de ajuda são apenas exemplos. Você também pode visualizar essa ajuda no telefone, em: Configurar > Ajuda. Moto G7 Play iii Conteúdo Configurar o telefone 1 Sobre o hardware 1 Inserir e remover o chip e os cartões SD 2 Copiar dados do telefone antigo 4 Gerenciar dual SIM 6 Configurar correio de voz 7 Configurar e-mail 8 Preparar-se para emergências 9 Deixar o telefone com a sua cara 10 Aprender os conceitos básicos 12 Sobre sua tela inicial 12 Sobre -

Virtualização De Processos Na Indústria 4.0

Virtualização de processos na Indústria 4.0 Mestrado em Engenharia Eletrotécnica Tiago Miguel dos Santos Neves Leiria, novembro de 2020 Virtualização de processos na Indústria 4.0 Mestrado em Engenharia Eletrotécnica Tiago Miguel dos Santos Neves Projeto realizado sob a orientação do Professor Doutor Eliseu Ribeiro e do Professor Doutor Luís Perdigoto Leiria, novembro de 2020 Originalidade e Direitos de Autor O presente projeto é original, elaborado unicamente para este fim, tendo sido devidamente citados todos os autores cujos estudos e publicações contribuíram para a elaborar. Reproduções parciais deste documento serão autorizadas na condição de que seja mencionado o Autor e feita referência ao ciclo de estudos no âmbito do qual o mesmo foi realizado, a saber, Curso de Mestrado em Engenharia Eletrotécnica, no ano letivo 2019/2020, da Escola Superior de Tecnologia e Gestão do Instituto Politécnico de Leiria, Portugal, e, bem assim, à data das provas públicas que visaram a avaliação destes trabalhos. iii Agradecimentos Ao elaborar este projeto, não poderia deixar de agradecer a todas as pessoas com quem troquei conhecimentos e contribuíram para que o projeto tivesse um melhor desenvolvimento. Aos orientadores deste projeto, Eliseu Ribeiro e Luís Perdigoto, pelo auxílio nas tarefas a realizar, indo ao encontro do que é o objetivo do projeto. Também pela disponibilização de um posto de trabalho na Siemens Automation Academy, com acesso a software e hardware utilizado neste projeto. À empresa CADFLOW, pela sua disponibilidade em demonstrar o funcionamento básico de software da Siemens® (NX e Mechatronics Concept Designer). A todos os colegas de mestrado, com quem tive o prazer de partilhar várias ideias na área da Eletrotécnia e com isso tornar mais completo o desenvolvimento do projeto. -

Manufacturer Model O2 Xda Atom O2 Xda Exec O2 Xda II Mini O2 Xda

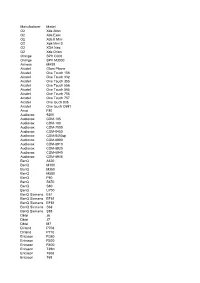

Manufacturer Model O2 Xda Atom O2 Xda Exec O2 Xda II Mini O2 Xda Mini S O2 XDA Neo O2 Xda Orion Orange SPV C600 Orange SPV M3000 Airness MK99 Alcatel Glam Phone Alcatel One Touch 156 Alcatel One Touch 332 Alcatel One Touch 355 Alcatel One Touch 556 Alcatel One Touch 565 Alcatel One Touch 756 Alcatel One Touch 757 Alcatel One touch 835 Alcatel One touch C651 Amoi F80 Audiovox 9200 Audiovox CDM-105 Audiovox CDM-180 Audiovox CDM-7000 Audiovox CDM-8450 Audiovox CDM-8450sp Audiovox CDM-8900 Audiovox CDM-8910 Audiovox CDM-8920 Audiovox CDM-8940 Audiovox CDM-8945 BenQ A520 BenQ M100 BenQ M350 BenQ M580 BenQ P50 BenQ S670 BenQ S80 BenQ U700 BenQ Siemens E61 BenQ Siemens EF51 BenQ Siemens EF81 BenQ Siemens S68 BenQ Siemens S88 Dbtel J6 Dbtel J7 Dbtel M7 Dirland P708 Dirland P710 Ericsson R380 Ericsson R520 Ericsson R600 Ericsson T39m Ericsson T60d Ericsson T65 Ericsson T68 Ericsson T68i Eten G500 Eten M500 Eten M600 Hitachi P300 HTC 3125 HTC 8300 HTC Dash HTC Excalibur HTC P3600 HTC S310 HTC S620 HTC SmartFlip HTC Star Trek HTC TyTN HTC Wing Innostream INNO30 Innostream INNO36 Innostream INNO55 Innostream INNO80 Innostream INNO89 Innostream INNO90 Innostream INNOA10 Innostream INNOA20 Innostream INNOP10 Kyocera Angel Kyocera Cyclops K325 Kyocera Dorado KX13 Kyocera Jet Kyocera K132 Kyocera K322 Kyocera K323 Kyocera Koi KX2 Kyocera KX12 Kyocera KX16 Kyocera KX160 Kyocera KX18 Kyocera KX440 Kyocera KX444 Kyocera Marbl Kyocera Slider RemixTM KX5 Kyocera SoHo KX1 Kyocera Strobe K612 LG 7050 LG 8000 LG A7110 LG AX-275 LG AX355 LG AX390 LG AX4270 LG -

Sendo X User Guide Chapter 17 Extras

User guide Table of Contents Copyright and Legal Information.................................................................................... iii Chapter 1 The Basics....................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 2 Phone Calls .................................................................................................................. 29 Chapter 3 Settings and Profiles...................................................................................................... 41 Chapter 4 Speed dials and voice commands.................................................................................. 53 Chapter 5 Contacts ....................................................................................................................... 55 Chapter 6 Messaging .................................................................................................................... 61 Chapter 7 Now! Screen................................................................................................................. 81 Chapter 8 Calendar and Tasks ...................................................................................................... 85 Chapter 9 Camera ........................................................................................................................90 Chapter 10 Image Editor ................................................................................................................. 96 Chapter 11 Camcorder ................................................................................................................ -

Motorola, Inc. 2006 Annual Report Motorola Is Known Around the World for Innovation and Leadership in Wireless and Broadband Communications

.06 Motorola, Inc. 2006 Annual Report Motorola is known around the world for innovation and leadership in wireless and broadband communications. Inspired by our vision of Seamless Mobility, the people of Motorola are committed to helping you get and stay connected simply and seamlessly to the people, information, and entertainment that you want and need. We do this by designing and delivering “must have” products, “must do” experiences and powerful networks – along with a full complement of support services. A Fortune 100 company with global presence and impact, Motorola had sales of US $42.9 billion in 2006. For more information about our company, our people and our innovations, please visit www.motorola.com. March 2007 Dear fellow stockholders, 2006 was a year of progress and challenges for Motorola. It was a year in which we achieved new highs in sales and shipments and added substantial talent and intellectual property. However, while our Networks & Enterprise and Connected Home Solutions businesses Ñnished 2006 strong, we were disappointed that our Mobile Devices business did not meet expectations in the latter half of the year. We remain conÑdent in our vision of seamless mobility Ó building simple and seamless connections to people, information, and entertainment Ó and the opportunity it brings to our business. As we focus on proÑtable growth and more selective pursuit of market share, we will continue to make investments for the future of Motorola. 2006 Ì Overview In 2006, sales grew 22% to a record $42.9 billion Ó the third consecutive year of double-digit revenue growth. Net earnings were $3.7 billion, or 8.5% of sales. -

Sendo X Quick Start Guide

Copyright © Sendo 2003. All rights reserved. Sendo, the Sendo logo, the Sendo “D” and the Sendo "X" phone are trademarks and/or registered trademarks of Sendo International Ltd and/or its affiliates. Copyright © Sendo 2003. Tutti i diritti riservati. Sendo, il logo Sendo, la "D" Sendo e il telefono Sendo modello "X" sono marchi di fabbrica e/o marchi registrati di Sendo International Ltd. e/o delle sue affiliate. Copyright © Sendo 2003. Reservados todos los derechos. Sendo, el logotipo de Sendo, la Quick start guide “D” de Sendo y el teléfono Sendo modelo "X" son marcas comerciales y/o marcas registradas de Sendo International Ltd. y/o de sus filiales. Contents 1 Introduction 1 2 Getting started 2 3 Getting to know your phone 6 4 Making and receiving calls 13 5 Sounds, photos, video, music 15 6 Sending and receiving messages 19 7 Safety Information 22 8 Regulatory Compliance and SAR Statements 27 9 End User Licence Agreement 35 10 Warranty Statements 38 Copyright and Legal Information Copyright and Legal Inform Legal Copyright and The wireless phone described in this guide be the trademarks of their respective is approved for use on the GSM and GPRS owners. networks operating on the 900, 1800 (DCS/ This product includes software licensed PCN) and 1900 (PCS) bands. It is approved from Symbian Ltd © 1998-2003. for use in the country where it was originally sold and may be approved for use in other This product contains software licensed countries. from Atelier. Copyright © 2002-2003 Atelier. All rights reserved (www.atelier.tm). Part No.