Chris Ware's Graphic Narratives As Literature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS American Comics SETH KUSHNER Pictures

LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS LEAPING TALL From the minds behind the acclaimed comics website Graphic NYC comes Leaping Tall Buildings, revealing the history of American comics through the stories of comics’ most important and influential creators—and tracing the medium’s journey all the way from its beginnings as junk culture for kids to its current status as legitimate literature and pop culture. Using interview-based essays, stunning portrait photography, and original art through various stages of development, this book delivers an in-depth, personal, behind-the-scenes account of the history of the American comic book. Subjects include: WILL EISNER (The Spirit, A Contract with God) STAN LEE (Marvel Comics) JULES FEIFFER (The Village Voice) Art SPIEGELMAN (Maus, In the Shadow of No Towers) American Comics Origins of The American Comics Origins of The JIM LEE (DC Comics Co-Publisher, Justice League) GRANT MORRISON (Supergods, All-Star Superman) NEIL GAIMAN (American Gods, Sandman) CHRIS WARE SETH KUSHNER IRVING CHRISTOPHER SETH KUSHNER IRVING CHRISTOPHER (Jimmy Corrigan, Acme Novelty Library) PAUL POPE (Batman: Year 100, Battling Boy) And many more, from the earliest cartoonists pictures pictures to the latest graphic novelists! words words This PDF is NOT the entire book LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS: The Origins of American Comics Photographs by Seth Kushner Text and interviews by Christopher Irving Published by To be released: May 2012 This PDF of Leaping Tall Buildings is only a preview and an uncorrected proof . Lifting -

Copyright 2013 Shawn Patrick Gilmore

Copyright 2013 Shawn Patrick Gilmore THE INVENTION OF THE GRAPHIC NOVEL: UNDERGROUND COMIX AND CORPORATE AESTHETICS BY SHAWN PATRICK GILMORE DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2013 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Michael Rothberg, Chair Professor Cary Nelson Associate Professor James Hansen Associate Professor Stephanie Foote ii Abstract This dissertation explores what I term the invention of the graphic novel, or more specifically, the process by which stories told in comics (or graphic narratives) form became longer, more complex, concerned with deeper themes and symbolism, and formally more coherent, ultimately requiring a new publication format, which came to be known as the graphic novel. This format was invented in fits and starts throughout the twentieth century, and I argue throughout this dissertation that only by examining the nuances of the publishing history of twentieth-century comics can we fully understand the process by which the graphic novel emerged. In particular, I show that previous studies of the history of comics tend to focus on one of two broad genealogies: 1) corporate, commercially-oriented, typically superhero-focused comic books, produced by teams of artists; 2) individually-produced, counter-cultural, typically autobiographical underground comix and their subsequent progeny. In this dissertation, I bring these two genealogies together, demonstrating that we can only truly understand the evolution of comics toward the graphic novel format by considering the movement of artists between these two camps and the works that they produced along the way. -

20 a 23.08.2013 Wilson/Lint: Biografía, Comic Independiente

Escola de Comunicações e Artes – Universidade de São Paulo – 20 a 23.08.2013 Wilson/Lint: biografía, comic independiente y la cualidad literaria Amadeo Gandolfo UBA (Facultad de Ciencias Sociales) – Conicet. Buenos Aires, Argentina. RESUMO En este trabajo analizaremos dos comics de Chris Ware y Daniel Clowes, “Lint” y “Wilson”, publicados durante 2010. Comparten una serie de características: son intentos de realizar la biografía de personajes sumamente desagradables, que en otro contexto serían vistos como villanos y no protagonistas de su propia historia; ambos siguen a sus personajes presentándonos todo lo que les sucede desde su punto de vista, obligándonos a ver las cosas como ellos las ven; ambos lidian con la propia historia del medio y las influencias de sus autores de una forma que incorpora estas en el texto; finalmente, la manera en que ambos fueron publicados habla de una situación cambiante dentro del campo del comic independiente norteamericano, su industria, sus formatos y las discusiones alrededor de su cualidad literaria. Observaremos ambas obras centrándonos fundamentalmente en la manera en que sus autores eligen abordar el género de la biografía y las decisiones estéticas que toman a la hora de representar la vida de sus protagonistas. Pero, también, colocaremos ambos trabajos en la obra más extensa de Ware y Clowes y en el lugar ocupan dentro de esa constelación conocida como comics independientes. También diseccionaremos sus elecciones formales en términos narrativos. PALAVRAS-CHAVE: comics independientes, biografía, cualidad literaria. 1. INTRODUCCIÓN El objetivo de este trabajo será el análisis de Lint y de Wilson, dos historietas autoconclusivas producidas por Chris Ware y Daniel Clowes, respectivamente, publicadas por la editorial Drawn & Quarterly durante el 2010. -

Aesthetics, Taste, and the Mind-Body Problem in American Independent Comics

PAPER TOWER: AESTHETICS, TASTE, AND THE MIND-BODY PROBLEM IN AMERICAN INDEPENDENT COMICS William Timothy Jones A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2014 Committee: Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Esther Clinton © 2014 William Timothy Jones All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Comics studies, as a relatively new field, is still building a canon. However, its criteria for canon-building has been modeled largely after modernist ideas about formal complexity and criteria for disinterested, detached, “objective” aesthetic judgment derived from one of the major philosophical debates in Western thought: the mind-body problem. This thesis analyzes two American independent comics in order to dissect the aspects of a comic work that allow it to be categorized as “art” in the canonical sense. Chris Ware’s Building Stories is a sprawling, Byzantine comic that exhibits characteristically modernist ideas about the subordination of the body to the mind and art’s relationship to mass culture. Rob Schrab’s Scud: The Disposable Assassin provides a counterpoint to Building Stories in its action-heavy stylistic approach, developing ideas about the merging of the mind and the body and the artistic and the commercial. Ultimately, this thesis advocates for a re -evaluation of comics criticism that values the subjective, emotional, and the popular as much as the “objective” areas of formal complexity and logic. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS To Anna O’Brien, for the original germ of this idea and hours of enlightening conversation and companionship. To Jeremy Wallach and Esther Clinton, whose emphatic response to the paper that eventually became this thesis was instrumental to my belief in the quality of my work. -

List of American Comics Creators 1 List of American Comics Creators

List of American comics creators 1 List of American comics creators This is a list of American comics creators. Although comics have different formats, this list covers creators of comic books, graphic novels and comic strips, along with early innovators. The list presents authors with the United States as their country of origin, although they may have published or now be resident in other countries. For other countries, see List of comic creators. Comic strip creators • Adams, Scott, creator of Dilbert • Ahern, Gene, creator of Our Boarding House, Room and Board, The Squirrel Cage and The Nut Bros. • Andres, Charles, creator of CPU Wars • Berndt, Walter, creator of Smitty • Bishop, Wally, creator of Muggs and Skeeter • Byrnes, Gene, creator of Reg'lar Fellers • Caniff, Milton, creator of Terry and the Pirates and Steve Canyon • Capp, Al, creator of Li'l Abner • Crane, Roy, creator of Captain Easy and Wash Tubbs • Crespo, Jaime, creator of Life on the Edge of Hell • Davis, Jim, creator of Garfield • Defries, Graham Francis, co-creator of Queens Counsel • Fagan, Kevin, creator of Drabble • Falk, Lee, creator of The Phantom and Mandrake the Magician • Fincher, Charles, creator of The Illustrated Daily Scribble and Thadeus & Weez • Griffith, Bill, creator of Zippy • Groening, Matt, creator of Life in Hell • Guindon, Dick, creator of The Carp Chronicles and Guindon • Guisewite, Cathy, creator of Cathy • Hagy, Jessica, creator of Indexed • Hamlin, V. T., creator of Alley Oop • Herriman, George, creator of Krazy Kat • Hess, Sol, creator with -

“Why So Serious?” Comics, Film and Politics, Or the Comic Book Film As the Answer to the Question of Identity and Narrative in a Post-9/11 World

ABSTRACT “WHY SO SERIOUS?” COMICS, FILM AND POLITICS, OR THE COMIC BOOK FILM AS THE ANSWER TO THE QUESTION OF IDENTITY AND NARRATIVE IN A POST-9/11 WORLD by Kyle Andrew Moody This thesis analyzes a trend in a subgenre of motion pictures that are designed to not only entertain, but also provide a message for the modern world after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. The analysis provides a critical look at three different films as artifacts of post-9/11 culture, showing how the integration of certain elements made them allegorical works regarding the status of the United States in the aftermath of the attacks. Jean Baudrillard‟s postmodern theory of simulation and simulacra was utilized to provide a context for the films that tap into themes reflecting post-9/11 reality. The results were analyzed by critically examining the source material, with a cultural criticism emerging regarding the progression of this subgenre of motion pictures as meaningful work. “WHY SO SERIOUS?” COMICS, FILM AND POLITICS, OR THE COMIC BOOK FILM AS THE ANSWER TO THE QUESTION OF IDENTITY AND NARRATIVE IN A POST-9/11 WORLD A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Communications Mass Communications Area by Kyle Andrew Moody Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2009 Advisor ___________________ Dr. Bruce Drushel Reader ___________________ Dr. Ronald Scott Reader ___________________ Dr. David Sholle TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .......................................................................................................................... III CHAPTER ONE: COMIC BOOK MOVIES AND THE REAL WORLD ............................................. 1 PURPOSE OF STUDY ................................................................................................................................... -

Report on Micro Data, Sorted by Title

English Language Graphic Novels Winners and Nominations of Comics and Graphic Novels Awards up to 2004 (list sorted first by title) Prepared by Olivier Charbonneau [email protected] Concordia University Data current as of May 18, 2004 PS. Please feel free to use and circulate this list – as long as the person using or receiving it does not use it for commercial purposes (selecting books for a library is OK) and agrees to send me a thank you letter at the following address: Olivier Charbonneau, Webster Library, room LB-279 Concordia University 1400 de Maisonneuve Blvd. W. Montreal, Quebec, H3G 1M8 Page 1 of 56 Title Publisher Wins Nominations 100 Unknown 1 Workman, John letterer 100 BulletDC 4 5 Azzarello, Brian writer Johnson, Dave cover 2002-2003 Risso, Eduardo artist 1001 Nights of BacchusDark Horse Comics 1 Schutz, Diana editor 1963 Image 2 Moore, Alan 20 Nude Dancers 20Tundra 1 Martin, Mark 20/20 VisionsDC/Vertigo 1 Alonso, Axel editor Berger, Karen editor 300Dark Horse Comics 2 2 Miller, Frank Varley, Lynn colorist 32 Stories Drawn & Quarterly 1 Tomine, Adrian A Contract with GodDC 2 Eisner, Will A Decade of Dark HorseDark Horse Comics 1 Stradley, Randy editor A History of ViolenceParadox 1 Wagner, John A Jew in Communist PragueNBM 1 4 Giardino, Vittorio Nantier, Terry editor A Small KillingVG Graphics/Dark Horse 1 1 Moore, Alan Zarate, Oscar A1Atomeka 1 2 Elliott, Dave editor Abraham StonePlatinum/Malibu 2 Kubert, Joe Page 2 of 56 Title Publisher Wins Nominations Acid Bath CaseKitchen Sink Press 1 Schreiner, Dave editor -

SEP 2010 Order Form PREVIEWS#264 MARVEL COMICS

Sep10 COF C1:COF C1.qxd 8/11/2010 12:22 PM Page 1 ORDERS DUE th 11 SEP 2010 SEP E COMIC H T SHOP’S CATALOG COF C2:Layout 1 8/6/2010 1:36 PM Page 1 COF Gem Page Sept:gem page v18n1.qxd 8/12/2010 8:55 AM Page 1 KULL: THE HATE WITCH #1 (OF 4) BATMAN: DARK HORSE COMICS THE DARK KNIGHT #1 DC COMICS HELLBOY: DOUBLE FEATURE OF EVIL DARK HORSE COMICS BATMAN, INC. #1 THE WALKING DEAD DC COMICS VOL. 13: TOO FAR GONE TP IMAGE COMICS MAGAZINE GEM OF THE MONTH DUNGEONS & DRAGONS #1 IDW PUBLISHING ..UTOPIAN #1 IMAGE COMICS WIZARD #232 WIZARD ENTERTAINMENT GENERATION HOPE #1 MARVEL COMICS COF FI page:FI 8/12/2010 2:47 PM Page 1 FEATURED ITEMS COMICS & GRAPHIC NOVELS ELMER GN G AMAZE INK/SLAVE LABOR GRAPHICS NIGHTMARES & FAIRY TALES: ANNABELLE‘S STORY #1 G AMAZE INK/SLAVE LABOR GRAPHICS S.E. HINTON‘S PUPPY SISTER GN G BLUEWATER PRODUCTIONS STAN LEE‘S TRAVELER #1 G BOOM! STUDIOS 1 1 DARKWING DUCK VOLUME 1: THE DUCK KNIGHT RETURNS TP G BOOM! STUDIOS LADY DEATH ORIGINS VOLUME 1 TP/HC G BOUNDLESS COMICS VAMPIRELLA #1 G D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT KEVIN SMITH‘S GREEN HORNET VOLUME 1: SINS OF THE FATHER TP G D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT ACME NOVELTY LIBRARY VOLUME 20 HC G DRAWN & QUARTERLY NORTH GUARD #1 G MOONSTONE LAST DAYS OF AMERICAN CRIME TP G RADICAL PUBLISHING ATOMIC ROBO AND THE DEADLY ART OF SCIENCE #1 G RED 5 COMICS BOOKS & MAGAZINES COMICS SHOP SC G COLLECTING AND COLLECTIBLES KRAZY KAT AND THE ART OF GEORGE HERRIMAN HC G COMICS SPYDA CREATIONS: STUDY OF THE SCULPTURAL METHOD SC G HOW-TO 2 STAR TREK: USS ENTERPRISE HAYNES OWNER‘S MANUAL HC G STAR -

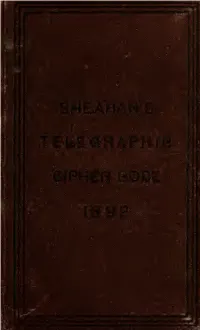

Cipher Code of Words, Phrases, Names of Organizations and Titles of Their

r/^i OF Words, Phrases, Names of Organizations and Ti- tles of Their Officers, Names of Principal Rail- roads, Months, Days, Time of Day, Al- phabet and Figures. FOR Use of Organizations of Railway Employes in TELEGRAPHIC CORRESPONDENCE ARRANGED BY Galesburg, 1892. Digitized by tine Internet Arcliive in 2010 witli funding from Dul<e University Libraries littp://www.arcliive.org/details/cipliercodeofworOOsliea PREFACE. In assuming, with pardonaljle pride, the labor of preparing a Cipher Code adapted to the business of the several Organizations of Railway Employes, the au- thor has endeavored to bring it thoroughly up to the requirements of the times. It is not to be expected that a work of this kind can be perfected by any one man in the first edition and the author requests those using this little book to note its short-comings for future reference, that he who undertakes the labor of revision, may have the benefit of their experience. The need of a work of this kind has at times been sorely felt by every organization and if this work meets the requirements so far as to lighten the burden of any organization in time of trouble, or to assist in gaining a single point in favor of the laboring man. then the author will feel that he has been fully repaid for his labor. To the several Organizations of Railway Emplo3'es this vrork is dedicated with the good will and best Avishes of the author. INSTRUCTIONS. This Cipher Code arranged for use of the several Organizations of Railway Employes is intended more especiall}' for Telegraphic Correspondence in time of trouble, when it is desirable or necessary to send tele- grams that can not be read by any but those for whom they are intended, as is the case in time of strikes or other important moves on the part of an Organization, as it is often necessary to use the Company's wire to reach members of the Organization on other parts of the road and unless such telegrams can be sent in a safe cipher it would be better the}^ were not sent, as the Company would be forewarned of every contem- plated move mentioned in the telegram. -

Narratives of Contamination and Mutation in Literatures of the Anthropocene Dissertation Presented in Partial

Radiant Beings: Narratives of Contamination and Mutation in Literatures of the Anthropocene Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Kristin Michelle Ferebee Graduate Program in English The Ohio State University 2019 Dissertation Committee Dr. Thomas S. Davis, Advisor Dr. Jared Gardner Dr. Brian McHale Dr. Rebekah Sheldon 1 Copyrighted by Kristin Michelle Ferebee 2019 2 Abstract The Anthropocene era— a term put forward to differentiate the timespan in which human activity has left a geological mark on the Earth, and which is most often now applied to what J.R. McNeill labels the post-1945 “Great Acceleration”— has seen a proliferation of narratives that center around questions of radioactive, toxic, and other bodily contamination and this contamination’s potential effects. Across literature, memoir, comics, television, and film, these narratives play out the cultural anxieties of a world that is itself increasingly figured as contaminated. In this dissertation, I read examples of these narratives as suggesting that behind these anxieties lies a more central anxiety concerning the sustainability of Western liberal humanism and its foundational human figure. Without celebrating contamination, I argue that the very concept of what it means to be “contaminated” must be rethought, as representations of the contaminated body shape and shaped by a nervous policing of what counts as “human.” To this end, I offer a strategy of posthuman/ist reading that draws on new materialist approaches from the Environmental Humanities, and mobilize this strategy to highlight the ways in which narratives of contamination from Marvel Comics to memoir are already rejecting the problematic ideology of the human and envisioning what might come next. -

Drawn & Quarterly Debuts on Comixology and Amazon's Kindle

Drawn & Quarterly debuts on comiXology and Amazon’s Kindle Store September 15th, 2015 — New York, NY— Drawn & Quarterly, comiXology and Amazon announced today a distribution agreement to sell Drawn & Quarterly’s digital comics and graphic novels across the comiXology platform as well as Amazon’s Kindle Store. Today’s debut sees such internationally renowned and bestselling Drawn & Quarterly titles as Lynda Barry’s One! Hundred! Demons; Guy Delisle’s Jerusalem: Chronicles from the Holy City; Rutu Modan’s Exit Wounds and Anders Nilsen’s Big Questions available on both comiXology and the Kindle Store “It is fitting that on our 25th anniversary, D+Q moves forward with our list digitally with comiXology and the Kindle Store,” said Drawn & Quarterly Publisher Peggy Burns, “ComiXology won us over with their understanding of not just the comics industry, but the medium itself. Their team understands just how carefully we consider the life of our books. They made us feel perfectly at ease and we look forward to a long relationship.” “Nothing gives me greater pleasure than having Drawn & Quarterly’s stellar catalog finally available digitally on both comiXology and Kindle,” said David Steinberger, comiXology’s co-founder and CEO. “D&Q celebrate their 25th birthday this year, but comiXology and Kindle fans are getting the gift by being able to read these amazing books on their devices.” Today’s digital debut of Drawn & Quarterly on comiXology and the Kindle Store sees all the following titles available: Woman Rebel: The Margaret Sanger Story by -

Chute and Dekoven Introduction to Graphic Narrative.Pdf

Chute and DeKoven 767 INTRODUCTION: f GRAPHIC NARRATIVE Hillary Chute and Marianne DeKoven The explosion of creative practice in the field of graphic narra- tive—which we may define as narrative work in the medium of com- ics—is one with which the academy is just catching up. We are only beginning to learn to pay attention in a sophisticated way to graphic narrative. (And while this special issue largely focuses on long-form work—"graphic narrative" is the term we prefer to "graphic novel," which can be a misnomer—we understand graphic narrative to en- compass a range of types of narrative work in comics.)1 Graphic nar- rative, through its most basic composition in frames and gutters—in which it is able to gesture at the pacing and rhythm of reading and looking through the various structures of each individual page—calls a reader's attention visually and spatially to the act, process, and duration of interpretation. Graphic narrative does the work of narra- tion at least in part through drawing—making the question of style legible—so it is a form that also always refuses a problematic trans- parency, through an explicit awareness of its own surfaces. Because of this foregrounding of the work of the hand, graphic narrative is an autographic form in which the mark of handwriting is an important part of the rich extra-semantic information a reader receives. And graphic narrative offers an intricately layered narrative language—the language of comics—that comprises the verbal, the visual, and the way these two representational modes interact on a page.