Promoting Patient Safety: Creating a Workable Reporting System T Melissa Chiang

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Redesigning the Fall Incident Report

A SAFETY INITIATIVE REDESIGNING THE FALL INCIDENT REPORT Joanne Elkins, MSN, RN, CPHQ, Lula Williams, MN, RN, CPHQ, Andrea M. Spehar, MS, DVM, MPH, Patricia A. Quigley, PhD, ARNP, CRRN, Tamala Gulley, MSCE, and Josefina Perez-Marrero, PhD Representing up to 89% of all reported adverse clinical incidents, falls are costly in both human and financial terms. Here’s how VISN 8 transformed their fall reporting process so that it could be used to drive system changes that would prevent falls. here seems to be a gen- tial sentinel events, with the goal of reported clinical incidents and are eral consensus among cli- improving the quality and safety of the most costly category in both nicians in this country patient care.1,2 In order for the RCA human and financial terms.7 T that most adverse health process to be successful in improv- In this article, we’ll discuss the care events result from system er- ing systems, investigators must VISN 8 incident reporting system rors. To correct such errors, in Feb- gather accurate, timely, and rele- and the process through which it ruary 1999, the VA established the vant data regarding clinical events was redesigned. We’ll outline the National Center for Patient Safety that are both ubiquitous and under- barriers we faced in implementing (NCPS), which implemented the reported.3–6 a VISN-wide incident report form process of root cause analysis In the fall of 1999, VA medical for patient falls and review the (RCA) to investigate and review center and clinic administrators types of data that must be gathered findings from all actual and poten- throughout Veterans Integrated in order for patterns, trends, and Service Network (VISN) 8 ac- root causes of such falls to be ana- knowledged that the incident re- lyzed successfully. -

Experiences from Ten Years of Incident Reporting in Health Care

Carlfjord et al. BMC Health Services Research (2018) 18:113 DOI 10.1186/s12913-018-2876-5 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Experiences from ten years of incident reporting in health care: a qualitative study among department managers and coordinators Siw Carlfjord1* , Annica Öhrn2 and Anna Gunnarsson3 Abstract Background: Incident reporting (IR) in health care has been advocated as a means to improve patient safety. The purpose of IR is to identify safety hazards and develop interventions to mitigate these hazards in order to reduce harm in health care. Using qualitative methods is a way to reveal how IR is used and perceived in health care practice. The aim of the present study was to explore the experiences of IR from two different perspectives, including heads of departments and IR coordinators, to better understand how they value the practice and their thoughts regarding future application. Methods: Data collection was performed in Östergötland County, Sweden, where an electronic IR system was implemented in 2004, and the authorities explicitly have advocated IR from that date. A purposive sample of nine heads of departments from three hospitals were interviewed, and two focus group discussions with IR coordinators took place. Data were analysed using qualitative content analysis. Results: Two main themes emerged from the data: “Incident reporting has come to stay” building on the categories entitled perceived advantages, observed changes and value of the IR system, and “Remaining challenges in incident reporting” including the categories entitled need for action, encouraged learning, continuous culture improvement, IR system development and proper use of IR. Conclusions: After 10 years, the practice of IR is widely accepted in the selected setting. -

Workplace Injury TRIAGE and REPORTING MEDCOR ON-LINE USER GUIDEBOOK

WORKPLACE INJURY TRIAGE AND REPORTING MEDCOR ON-LINE USER GUIDEBOOK (800) 775-5866 24 HOURS / 7 DAYS A WEEK TITLE Copyright © 2005-2008 Medcor, Inc. All rights reserved. TABLE OTFIT CONLE TENTS Overview The Problem .................................................1 The Solution .................................................1 The Triage Call Process—How it Works When Employee Injury Occurs...................................2 Placing the Triage Call . .2 Injury Assessment .............................................3 Treatment Recommendations ....................................3 Triage Report Information . 3 Referral Off-Site . 4 Post-Injury Resource...........................................4 Call Confirmation.............................................4 Injury Reports................................................4 Follow-Up Calls . 4 Waiting to Speak with a Nurse . .5 Frequently Asked Questions . .6 Sample Triage Incident Report ..................................7 Sample Self-Care Instructions...................................8 OVERVIEW The Problem Responding to work-related injuries is challenging: • Employees who work alone or in small worksites have limited access to immediate medical assistance in case of injury. • Supervisors who respond to injuries often lack proper medical training or experience to determine the seriousness of the injury and the appropriate response. • Minor injuries such as strains and sprains that would respond favorably to appropriate on-site first aid are often referred off-site for care that is more expensive and more time consuming but no more effective. • Off-site clinics and hospitals are often not familiar with the workplace environment, first aid options, modified duty, or return-to-work programs. • When injured employees are referred to an out-of-network clinic or hospital, they often become caught up in a system of care that thrives on increased utilization. This can lengthen the employees’ recovery time and time away from work, and it reduces the company’s ability to help direct effective care. -

Iowa Medicaid Critical Incident Report

Iowa Medicaid Critical Incident Report Date Received Incident ID Staff Reviewer Instructions: Submit all pages of this form with as much information as possible within the required reporting timeframes. Incident Status: Managed Care Organization: Initial (pending further investigation) Amerigroup Iowa Completed (investigation completed) Iowa Total Care Additional information added Non-MCO National Provider Identifier Phone Number Provider or Agency Name Provider Address Information City State Zip Code Provider/Facility Reporter’s First Name Last Name Title Email Phone Number Point of contact to discuss incident if different from reporter: Reporting Party First Name Last Name Phone Number Medicaid State Number First Name Last Name Address City State Zip Code Date of Birth Age Medicaid Member Member’s gender: Male Female AIDS/HIV Habilitation MFP Brain Injury Health and Disability Other (non-waiver): Children’s Mental Health Intellectual Disability Describe: Service Programs Elderly Physical Disability First Name Last Name Address City State Zip Code Email Phone Number Case manager contacted member within 24 hours of discovering incident? Yes No Case Case Manager (CM) Date CM Contacted Member Time CM Contacted Member 470-4698 (Rev. 4/21) Page 1 of 6 Date Incident Occurred (required) Time of Incident a.m. p.m. Unknown Date Incident Discovered (required) Was the incident witnessed? Yes No Incident Person to learn of incident: First Name Last Name Title Select Location Type (If other, specify.) Member’s home Community Other location Living alone Work State facility Living with relatives School Correctional facility or jail Living with unrelated person Vehicle Nursing facility RCF Day program Hospital or clinic Assisted living Other: PMIC Other: Other: Name of Location or Facility Location of Incident Location or Facility Address City State Zip Code People Present During Incident (Provide name of person, initials if a member, and the person’s relationship to the member. -

Healthcare Professional Experiences of Clinical Incident in Hong Kong: a Qualitative Study

Risk Management and Healthcare Policy Dovepress open access to scientific and medical research Open Access Full Text Article ORIGINAL RESEARCH Healthcare Professional Experiences of Clinical Incident in Hong Kong: A Qualitative Study This article was published in the following Dove Press journal: Risk Management and Healthcare Policy Leung Andrew Luk1 Background: Studies showed that adverse events within health care settings can lead to two Fung Kam Iris Lee 1 victims. The first victim is the patient and family and the second victim is the involved Chi Shan Lam2 healthcare professionals. However, there is a lack of research studying the experiences of Hing Yu So 3 healthcare professionals encountering clinical incidents in Hong Kong. This paper reports Yuk Yi Michelle Wong3 a qualitative study in exploring the healthcare professional experiences of clinical incident, their impacts and needs. Wai Sze Wacy Lui4 Methods: This study is the second part of the mixed research method with two studies 1Nethersole Institute of Continuing conducted in a cluster of hospitals in Hong Kong. Study 1 was a quantitative questionnaire Holistic Health Education (NICHE), Alice Ho Miu Ling Nethersole Charity survey and Study 2 was a qualitative In-Depth Interview. In study 2, a semi-interview guide Foundation, Hong Kong; 2Department of was used. Anesthesiology & Operating Services, Results: Results showed that symptoms experienced after the clinical incident were mostly AHNH &NDH, Hong Kong; 3Quality & Safety, New Territories East Cluster from psychological, physical, then social and lastly spiritual aspects which were consistent (Q&S, NTEC), Hong Kong; 4Oasis with those found in study 1 and other studies. -

Perceived Barriers in Incident Reporting Among Health Professionals in a Secondary Care Hospital in Makassar, Indonesia

Faisal & Handayani (2021): Perceive barriers in incident reporting among health professionals in Indonesia Jan 2021 Vol. 24 Issue 01 Perceived barriers in incident reporting among health professionals in a secondary care hospital in Makassar, Indonesia Shah Faisal1*, Meliana Handayani2 1Department of Pharmacy Practice, Faculty of Pharmacy, Universitas Airlangga 2Master of Public Health, Department of Administration and health policy, Faculty of Public Health, Universitas Airlangga *Corresponding author: Shah Faisal* Department of Pharmacy Practice Faculty of Pharmacy, Universitas Airlangga, JalanDokter Ir. Haji Soekarno, Mulyorejo Surabaya, 60115, JawaTimur, Indonesia Email: [email protected] Phone No: +62-82129129043 Abstract Background :Underreporting is a major issue around the globe while using incident reporting systems to improve patient safety. A confined concept of reporting exists in health care settings in Indonesia. Aims:Toinvestigate the perceived barriers in incident reporting among the health professionals.Settings and Design:The study was conducted among 84 randomly selected health professionals ina secondary care hospital in Makassar, Indonesia.Methods and Material:A descriptive cross-sectional study was completed using a self-created questionnaire and was collected back. The questionnaire consisted of 16 questions containing the obstacles in reporting which then grouped into four major dimensions of fear, uselessness, risk acceptance, and practical reasons. Statistical analysis used:The data was analyzed using SPSS version 25. Descriptive statistics using frequencies were used to analyze the perceived barriers.Results:A total of 84 participants completed the questionnaire. The highest barrier in reporting was forgetfulness by 14 (16.7%) of the participants who were strongly agreed, and 30 (35.7%) were agreed. The second highest barrier was fear of being investigated by 30 (35.7%) of participants who were agreed. -

Incident Report

THE JOHNS HOPKINS INSTITUTIONS EMPLOYEE REPORT OF INCIDENT INSTRUCTIONS SERIOUS INJURY/ILLNESS: If an employee is seriously injured or becomes acutely ill on the job and needs immediate medical attention, call 911. Examples of serious medical conditions include loss of consciousness, life threatening injury, seizure, and/or change in mental status. In such cases the employee should be accompanied by a supervisor or coworker. If there is a question of severity, contact the appropriate clinic for assistance in determining the appropriate care facility. See the list of phone numbers in #5 below. Employees: Employees shall wash hands and any other skin with soap and water, or flush mucous membranes with water immediately or as soon as feasible following contact of such body areas with blood or other potentially infectious materials 1. Report any work-related injury or illness, no matter how minor, to your supervisor immediately. 2. Obtain a completed Employee Report of Incident form from your supervisor and proceed to the appropriate clinic listed in # 5 below. 3. For EYE INJURIES report directly to the Emergency Room of the appropriate campus. Refer to policies HSE004. For bloodborne pathogen exposures, call 5-STIX (5-7849) inside the hospital or 410-955-7849 if you are calling from outside. 4. For needlesticks or other BLOODBORNE PATHOGEN EXPOSURES call the appropriate clinic for further instructions. Refer to BLOODBORNE PATHOGEN EXPOSURES in Policy HSE004 for details. • East Baltimore Campus: Call 5-STIX 5-7849 immediately. During the hours of 7:30AM – 4 PM, the employee will be given instructions to report to clinic (Blalock 139) immediately. -

Marshfield Clinic Incident Reporting System Policy

Incident Reporting System Document ID: 3PE3E66MX2CW-2-1140 Effective Date: 4/22/2016 Incident Reporting System 1. SCOPE 1.1. System-wide, including Marshfield Clinic Health System, Inc. and its affiliated organizations who adopt this policy including Marshfield Clinic, Inc., Family Health Center of Marshfield, Inc., Lakeview Medical Center, Inc. of Rice Lake, MCHS Hospitals, Inc., and all facilities owned and/or operated by the aforementioned organizations including all Marshfield Clinic locations, and Marshfield Clinic Regional Medical Center; however excluding MCIS, Inc., Marshfield Food Safety, LLC, Security Health Plan of Wisconsin, Inc., and Flambeau Hospital. 1.2. Incidents involving employee health and safety are outside the scope of this policy. 2. DEFINITIONS & EXPLANATIONS OF TERMS 2.1. Reportable Incident: An occurrence or event requiring documentation in the Incident Reporting System with appropriate follow-up by Marshfield Clinic. 2.2. General Liability Incident: An accident occurring on any Marshfield Clinic premises involving injury to a patient or any visitor resulting from a slip, trip, or fall or other event and occurring outside the scope of patient care or related health care services. 2.3. Adverse Medical Device Incident: An event involving death or serious bodily injury caused, in whole or in part, by an instrument, apparatus or other article that is used to prevent, diagnose, mitigate or treat a disease or to affect the structure or function of the body with the exception of drugs. Incidents involving heparin- containing flush solutions are considered an adverse medical device incident. 2.4. Product Recall Incidents: Includes a voluntary or mandatory recall; safety alert; notice of product defect, failure or deficiency; or other similar notices issued by a manufacturer, vendor, or any federal or state agency and received by Marshfield Clinic which may impact the health and safety of Marshfield Clinic patients. -

Medical Staff Code of Conduct Policy

Section: Medical Staff Subject: Code of Conduct POLICIES AND PROCEDURES MANUAL Number: MS43 Attachment A-Expectations of Physicians Attachment B- DHHS Mandatory Reporting System Department Attachments: Requirements Date Effective: 3/24/03 Supersedes: 5/24/05, 5/21/07, 2/13/09, 7/19/10, 4/15/13, Date Reviewed: 3/19/15, 4/17/17, 5/2019 CODE OF CONDUCT POLICY This policy applies to members of the Medical/Dental Staff (henceforth referred to as Medical Staff). It is the policy of this hospital that all individuals within its facility be treated courteously, respectfully, and with dignity. To that end, the hospital requires all individuals, including employees, medical staff, allied health professionals, and other practitioners to conduct themselves in a professional and cooperative manner in all Nebraska Medicine facilities (henceforth referred to as Hospital). If an employee's conduct is disruptive, the matter shall be addressed in accordance with hospital employment policies. If the conduct of a Medical Staff member or allied health practitioner is disruptive, the matter shall be addressed In accordance with this policy. Any medical staff, allied health professional, employee, patient or visitor may report potentially disruptive conduct. Medical Students, Residents and House Officers shall be addressed in accordance with this policy. The Training Director, Chairman or Dean, as applicable, will receive notification from the Medical Staff President of the conduct and action taken. Any cost associated with recommendation for action will be the responsibility of the training program and/or department. OBJECTIVE The objective of this policy is to ensure optimum patient care by promoting a safe, cooperative and professional health care environment and to prevent or eliminate, to the extent possible, conduct that disrupts the operation of the Hospital, affects the ability of others to do their jobs, creates a "hostile work environment" for Hospital employees or other Medical Staff members, or interferes with an individual's ability to practice competently. -

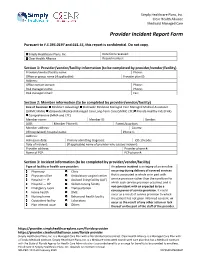

Provider Incident Report Form

Simply Healthcare Plans, Inc. Clear Health Alliance Medicaid Managed Care Provider Incident Report Form Pursuant to F.S 395.0197 and 641.55, this report is confidential. Do not copy. Simply Healthcare Plans, Inc. Date form received: Clear Health Alliance Record number: Section 1: Provider/vendor/facility information (to be completed by provider/vendor/facility) Provider/vendor/facility name: Phone: Office or group name (if applicable): Provider plan ID: Address: Office contact person: Phone: Risk manager name: Phone: Risk manager email: Fax: Section 2: Member information (to be completed by provider/vendor/facility) Line of business: Medicare Advantage Statewide Medicaid Managed Care Managed Medical Assistance (SMMC MMA) Statewide Medicaid Managed Care Long-Term Care (SMMC LTC) Florida Healthy Kids (FHK) Comprehensive (MMA and LTC) Member name: Member ID: Gender: DOB: Member Phone #: Parent/guardian: Member address: County: (If hospitalized) hospital name: Phone #: Address: Admission date: Primary admitting diagnosis: ICD-10 code: Date of incident: (If applicable) name of provider who caused incident: Provider address: Provider phone #: Name of PCP: PCP phone #: Section 3: Incident information (to be completed by provider/vendor/facility) Type of facility or health care provider: An adverse incident is an injury of an enrollee Pharmacy Clinic occurring during delivery of covered services Physician office Ambulatory surgical center that is associated in whole or in part with Hospital — IP Assisted living facility (ALF) service provision rather than the condition for Hospital — OP Skilled nursing facility which such service provision occurred, and is not consistent with or expected to be a Emergency room Transportation consequence of service provision. -

Institutional Medical Incident Medical Reporting Systems: a Review

id6634670 pdfMachine by Broadgun Software - a great PDF writer! - a great PDF creator! - http://www.pdfmachine.com http://www.broadgun.com Institutional Medical Incident Medical Reporting Systems: A Review Other Titles in this Series HTA Initiative #1 Framework for Regional Health Authorities to Make Optimal Use of Health Technology Assessment HTA Initiative #2 Making Managerial Health Care Decisions in Complex High Velocity Environments For more information contact: HTA Initiative #3 Proceedings of the Conference on Evidence Based Health Technology Assessment Unit Decision Making: How to Keep Score Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research HTA Initiative #4 AHFMR Screening Procedure for Use When Considering the Implementation of Health Suite 1500 Technology (Released April 2001) 10104 – 103 Avenue Edmonton, Alberta HTA Initiative #5 Priority Setting in Health Care: Canada T5J 4A7 From Research to Practice Tel: 780 423-5727 HTA Initiative #6 AHFMR Screening Procedure for Use When Fax: 780 429-3509 Considering the Implementation of Health Technology (Released April 2002) HTA Initiative #7 Local Health Technology Assessment: A Guide for Health Authorities HTA Initiative #8 Minimally Invasive Hip Arthroplasty HTA Initiative #9 Elements of Effectiveness for Health Technology Assessment Programs HTA Initiative #10 Emergency Department Fast-track System HTA Initiative #11 Decision-Making for Health Care Systems: A Legal Perspective HTA Initiative #12 Review of Health Technology Assessment Skills Development Program HTA Initiative #13 -

Ohio Uniform Incident Report (UIR)

Ohio Uniform Incident Report (UIR) Training Manual August 2011 Table of Contents Ohio Uniform Incident Report Forms Definition of an Incident…………………………………………………………………………. .....1 Administrative Section ........................................................................................................................2 Offense Section .....................................................................................................................................7 Hate Bias Crime Information and Codes ...................................................................................9 Larceny Type Codes ................................................................................................................14 Offenses that require the Type of Criminal Activity Section ..................................................17 Location of Offense Information and Codes ...........................................................................20 Type of Weapon Force Used ...................................................................................................26 Method of Entry .......................................................................................................................27 Methods of Operation Codes ...................................................................................................29 Offenses that require the Cargo Theft Y or N entry………………………………………… 32 Victim Section.....................................................................................................................................33