Change Maker's Guide to New Horizons

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Temple Library Database 2017-05-17

Temple Sholom Library 6/9/2017 BOOK PUB CALL TITLE AUTHOR CATEGORY KEYWORDS FORMAT DATE NUMBER Children's Books : Literature : 10 Traditional Jewish Children's Stories Goldreich, Gloria Hardcover 1996 Children's stories, Hebrew, Legends, Jewish J 185.6 Go Classics by Age : General Feldman, 100+ Jewish Art Projects for Children Paperback 1996 Religion Biblical Studies Bible. O.T. Pentateuch Textbooks Margaret A. Language selfstudy & 1001 Yiddish Proverbs Kogos, Fred Paperback 1990 phrasebooks 101 Classic Jewish Jokes : Jewish Humor from Groucho Marx to Jerry Menchin, Robert Paperback 1997 Entertainment : Humor : General Jewish wit and humor 550.7 Seinfeld World War, 19141918 Peace, World War, 19141918 1918: War and Peace Dallas, Gregor Hardcover 2001 20th Century World History Armistices Kipfer, Barbara English language Style Handbooks, manuals,, etc, 21ST Century Style Manual Paperback 1993 English Composition Ann English language Usage Dictionaries 26 Big Things Small Hands Do Paratore, Coleen Paperback 1905 Tikkun olam J Pa 300 ways to ask the four questions : from Zulu to Abkhaz : an extraordinary survey of the world's languages through the prism of the Spiegel, Murray Hardcover 1905 Passover Mah nishtannah Translations 244.4 Sp Haggadah 5,600 Jokes for All Occasions Meiers, Mildred Hardcover 1905 Jewish Humor Jewish Humor 550.7 Me 50 Ways to be Jewish: Or, Simon & Garfunkel, Jesus loves you less Forman, David J. Hardcover 2001 Jewish living Jewish way of life, Judaism 20th century 246 Fo than you will know 700 sundays Crystal, Billy Hardcover 1905 Crystal, Billy Crystal, Billy, Comedians United States Biography B Cr FinkWhitman, 94 Maidens Paperback 1905 Fiction F Fi Rhonda A Backpack, A Bear, and Eight Crates of Vodka Golinkin, Lev Paperback 1905 Biographies & Memoirs B Go Jews Folklore, Folklore Europe, Eastern, Yiddish Folk A Big Quiet House Forest, Heather Hardcover 1996 Folklore J 185.6 Fo Tales Jews New York (State) New York Social, life and customs, Immigrants New York (State) New York , A Bintel brief. -

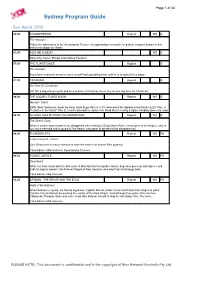

Sydney Program Guide

Page 1 of 34 Sydney Program Guide Sun Aug 5, 2012 06:00 THUNDERBIRDS Repeat WS G The Imposter Follow the adventures of the International Rescue, an organisation created to help those in grave danger in this marionette puppetry classic. 07:00 KIDS WB SUNDAY WS G Hosted by Lauren Phillips and Andrew Faulkner. 07:00 THE FLINTSTONES Repeat G The Gambler Psychiatric treatment seems to have cured Fred's gambling fever until he is tempted into a wager. 07:30 TAZ-MANIA Repeat G No Time For Christmas Taz fills a bag with presents and tries to deliver Christmas cheer, but no one has time for Christmas. 08:00 THE LOONEY TUNES SHOW Repeat WS G Monster Talent Daffy takes Gossamer under his wing, while Bugs stars in a TV commercial for Speedy's new frozen pizza. Plus, in "A Zipline in the Sand," Wile E. Coyote attempts to capture the Road Runner using a zipline hanging above the road. 08:30 SCOOBY DOO MYSTERY INCORPORATED Repeat WS G The Siren's Song When a sardine boat mysteriously disappears when fishing in Dead Man's Point, Velma goes to investigate, only to run into a mermaid and a couple of fish freaks, who seem to be behind the disappearings. 09:00 THUNDERCATS Repeat WS PG Trials of Lion-O - Part 2 Lion-O launches a rescue mission to save the team from Mumm-Ra's pyramid. Cons.Advice: Mild Violence, Supernatural Themes 09:30 YOUNG JUSTICE Repeat WS PG Disordered While the team deals with the aftermath of Miss Martian's telepathic attack, Superboy goes out with Sphere and finds its original owners: the Forever People of New Genesis, who want their technology back. -

O.305.438.9200 - [email protected]

404 Washington Ave., Suite 730 - Miami Beach, FL 33139- o.305.438.9200 - [email protected] IF VOLUME 113, No.309 FACEBOOK.COM/MIAMIHERALD WINNER OF 20 Early storms TUESDAY JULY192016 $1 STAY CONNECTED MIAMIHERALD.COM TWITTER.COM/MIAMIHERALD PULITZER PRIZES 91°/79° See 4B H1 WORLD SCRUTINY ON IRAN NUCLEAR DEAL Documents obtained by the AP show that nuclear limits imposed on Iran will start to ease before the accord expires. 12A TROPICAL LIFE OLYMPIC SPLASH FOR FOOTVOLLEY? In footvolley — a new demonstration sport at the Rio Olympics — you can’t use your hands to get the ball over the net, but you JOHN LOCHER AP Illinois delegate Christian Gramm, left, and other delegates react as some call for a roll call vote on the adoption of the rules Monday at the can use your feet. 1C Republican National Convention in Cleveland. ‘Hold the vote!’ the anti-Trump faction chanted. ‘Roll call!’ Their microphones were shut off. CAMPAIGN 2016 | REPUBLICAN NATIONAL CONVENTION Trump’s law-and-order night preceded by a day of chaos delegates tried one last time to insurrection withdrew — appar- SPORTS ........................................................ BY PATRICIA MAZZEI prevent Donald Trump from ently pressured by party leaders Political unrest marked the [email protected] winning the GOP’s presi- who didn’t want to be embar- FINS SIGN FOSTER first day of the Republican dential nomination. rassed. The maneuver led to National Convention CLEVELAND They amassed raucous protests on the con- TO 1-YEAR DEAL ........................................................ It was supposed to be law-and- enough support to The Dolphins signed It culminated with a order night at the Republican force a full vote of SEE CONVENTION, 2A veteran running back Arian last-ditch protest by National Convention. -

THE TUFTS DAILY Est

Where You Rain Read It First 57/35 THE TUFTS DAILY Est. 1980 VOLUME LXVIII, NUMBER 47 MONDAY, NOVEMBER 17, 2014 TUFTSDAILY.COM Cage Rage sees popular headliner, lower ticket sales by Jei-Jei Tan concert, according to Gibb. She noted “There were just so many unfortunate energy on stage was a lot of fun, and their Daily Editorial Board that she heard both positive and negative things about this year’s [concert],” she said, performance was impressive.” reviews of the performance, although she adding that the security measures at the According to Gibb, MS MR had just The fifth annual Cage Rage concert, believed that overall the set did get better entrance were excessive and annoying. finished a tour, and Cage Rage was its last featuring headliner MS MR and open- and still went well. MS MR, which Marber described as an show of the year ers STRFKR and Gentlemen Hall, was held Annie Gill, a sophomore who attended “indie-pop-rock boom explosion,” was very “They were really excited to close it out at Carzo Cage in Cousens Gymnasium this the concert, said that she thought STRFKR well received. with a college show,” she said. Saturday evening. was a little disappointing and that she “The crowd responded really positively Marber explained that the duo had met According to Concert Board Co-Chairs wished they had played their own songs. to them, and we confirmed this by talking each other in college, and he noted that Matthew Marber and Kathryn Gibb, Sophomore Miranda Willson said she to the artists after the show,” he said. -

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Šárka Tripesová The Anatomy of Humour in the Situation Comedy Seinfeld Bachelor‟s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: Mgr. Pavel Drábek, Ph.D. 2010 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. …………………………………………….. Šárka Tripesová ii Acknowledgement I would like to thank Mgr. Pavel Drábek, Ph.D. for the invaluable guidance he provided me as a supervisor. Also, my special thanks go to my boyfriend and friends for their helpful discussions and to my family for their support. iii Table of Contents 1 INTRODUCTION 1 2 SEINFELD AS A SITUATION COMEDY 3 2.1 SEINFELD SERIES: THE REALITY AND THE SHOW 3 2.2 SITUATION COMEDY 6 2.3 THE PROCESS OF CREATING A SEINFELD EPISODE 8 2.4 METATHEATRICAL APPROACH 9 2.5 THE DEPICTION OF CHARACTERS 10 3 THE TECHNIQUES OF HUMOUR DELIVERY 12 3.1 VERBAL TECHNIQUES 12 3.1.1 DIALOGUES 12 3.1.2 MONOLOGUES 17 3.2 NON-VERBAL TECHNIQUES 20 3.2.1 PHYSICAL COMEDY AND PANTOMIMIC FEATURES 20 3.2.2 MONTAGE 24 3.3 COMBINED TECHNIQUES 27 3.3.1 GAG 27 4 THE METHODS CAUSING COMICAL EFFECT 30 4.1 SEINFELD LANGUAGE 30 4.2 METAPHORICAL EXPRESSION 32 4.3 THE TWIST OF PERSPECTIVE 35 4.4 CONTRAST 40 iv 4.5 EXAGGERATION AND CARICATURE 43 4.6 STAND-UP 47 4.7 RUNNING GAG 49 4.8 RIDICULE AND SELF-RIDICULE 50 5 CONCLUSION 59 6 SUMMARY 60 7 SHRNUTÍ 61 8 PRIMARY SOURCES 62 9 REFERENCES 70 v 1 Introduction Everyone as a member of society experiences everyday routine and recurring events. -

2010: the Best Women's Stage Monologues and Scenes

2010: The Best Women’s Stage Monologues and Scenes Edited and with a Foreword by Lawrence Harbison MONOLOGUE AND SCENE STUDY SERIES A SMITH AND KRAUS BOOK HANOVER, NEW HAMPSHIRE SMITHANDKRAUS.COM Published by Smith and Kraus, Inc. 177 Lyme Road, Hanover, NH 03755 SmithandKraus.com © 2010 by Smith and Kraus, Inc. All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America CAUTION: Professionals and amateurs are hereby warned that the plays represented in this book are subject to a royalty. They are fully protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America, and of all countries covered by the International Copy- right Union (including the Dominion of Canada and the rest of the British Common- wealth), and of all countries covered by the Pan-American Copyright Convention and the Universal Copyright Convention, and of all countries with which the United States has reciprocal copyright relations. All rights, including professional, amateur, motion picture, recitation, lecturing, public reading, radio broadcasting, television, video or sound taping, all other forms of mechanical or electronic reproductions such as infor- mation storage and retrieval systems and photocopying, and the rights of translation into foreign languages, are strictly reserved. Pages 187 –193 constitute an extension of this copyright page. First Edition: September 2010 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Cover design by Dan Mehling, [email protected] Book design and production by Julia Hill Gignoux, Freedom Hill Design and Book Production The Scene Study Series 1067-3253 ISBN-13 978-1-57525-774-7 / ISBN-10 1-57525-774-2 Library of Congress Control Number: 2010931856 NOTE: These scenes are intended to be used for audition and class study; permission is not required to use the material for those purposes. -

Download The

COMPLIMENTARY AUGUSTMAY 2021 2020 smithfieldtimesri.net Peaceful brook that runs along the Stillwater Scenic Trail. Photo courtesy of Elaine S. Amoriggi BOSTON MA BOSTON 55800 PERMIT NO. PERMIT PAID Our customers U.S. POSTAGE U.S. ECRWSS Local Postal Customer Postal Local are our owners. PRSRT STD PRSRT Federally insured by NCUA PROACTIVE PROACTIVE SOPHISTICATED CARE SOPHISTICATED CARE OUR PATIENTS ENJOY: OUR • Therapy PATIENTS up to 7 Days aENJOY: Week Raising the bar in the delivery • TherapyBrand New up State-of-the-artto 7 Days a Week Rehab Gym & Equipment Raisingof short-term the bar in rehabilitative the delivery • BrandIndividualized New State-of-the-art Evaluations & Rehab Treatment Gym Programs & Equipment ofand short-term skilled nursing rehabilitative care in • IndividualizedComprehensive Evaluations Discharge Planning& Treatment that Programs Begins on Day One and skilled nursing care in • ComprehensiveSemi-Private and Discharge Private Rooms Planning with that Cable Begins TV on Day One Northern Rhode Island • Semi-PrivateConcierge Services and Private Rooms with Cable TV Northern Rhode Island • Concierge Services CARDIAC ORTHOPEDIC PULMONARY REHABILITATION CARDIAC REHABILITATION ORTHOPEDIC PULMONARY CARE Under the REHABILITATION direction of a leading • Physicians REHABILITATION & Physiatrist On-Site • Tracheostomy Care CARE Cardiologist/Pulmonologist, our specialized Under the direction of a leading • PhysiciansIndividualized & Physiatrist Aggressive On-Site Rehab • TracheostomyRespiratory Therapists Care nurses provide -

The Student Newspaper of North Carolina State University Since 1920

THE STUDENT NEWSPAPER OF NORTH CAROLINA STATE UNIVERSITY SINCE 1920 w MONDAY DECEMBER 1 2003 TECH. A 1 Raleigh, North Carolina. Thanksgiving break draws families together Campus was bare this week- short time, campus was practi— in some ofthe scenery and a rather isn’t about the ambiance but the end as students traveled to cally deserted when students left nice buffet lunch,” Biram said. “It company. celebrate Thanksgiving with their dorms and migrated back to was really cool; Doron is really “As long as you’re with your their homes where they could rest, peaceful and has a great scene.” family and loved ones, you could family andfriends. eat and prepare for the last week of Biram has been to this particular be in a car and it would still be the fall semester. town with his family before, but Thanksgiving,” Biram said. Michele DeCamp Many students travel to other this holiday was especially fun for Others students had plans to _ News Editor places for the holidays, but some the foursome. travel, but the flu bug got in the students actually traveled with “It turned out great. I was with way. Stephany Dunstan, a sopho- their families to enjoy their days my folks, I was with my brother, more in arts applications, moved They came back slowly. All off. Paul Biram, a freshman in com- , we laughed, we tasted wine, we had from Norfolk, Va. to Raleigh six weekend, students could be seen puter science, went toVirginia with supper, we played games, we just years ago, but the majority of her dragging duffel bags and clean his parents and brother. -

Vol . 1 1 | May 2 0

V OL.11 | MAY2019 What an opulent afternoon it was! We celebrated Mother’s Day with Upcoming District 1 Events six enchanting stories and many returning guests. District 1 Spring Conference Have you heard of liberosis? It’s a desire to care about things. less th With “State of Liberosis,” yours truly shared the story of how she joined Date: Saturday, May 18 Toastmasters, interspersed with little rants about how ridiculous Time: 7am – 5pm English is. Location: Renaissance LAX Hotel Mallery McMurtrey told us how choosing the right color palette 9620 Airport Blvd, LA, CA 90045 empowers us. It was the best speech I’ve heard her give. With this speech, she achieved a new shiny designation. Congrats, Mallery Upcoming StoryMasters Meetings McMurtrey, Advanced Communicator Bronze! (*Bling*) StoryMasters I always appreciate when our proficient speakers share storytelling tips Every second Sunday at 3-5pm and Antoinette Byron is the perfect person to talk about body 3720 Monteith Drive, View Park, CA 90043 language. Her movements are always purposeful and graceful. With Upcoming meetings: her “Something in the Way You Move,” we learned how to stand, move, • June 9 and make eye contact on the stage. • July 14 Join us on second Sundays to enjoy Who loves France? Jacki Williams-Jones does! In “Tasting the Stars, some wonderful stories and Part 2,” she educated us on Champagne, explaining the difference conversations with other storytellers. between Champagne and Sparkling Wine with charm and humor. Please RSVP to Tina Tomiyama at Jacki, take us on a BevMo tour! [email protected] so that we can We also had two beautiful stories honoring Mother’s Day. -

Big Block of Cheese Special JOSH: These

The West Wing Weekly 0.11: Big Block of Cheese Special JOSH: These cheese episodes have been a cottage industry for us. HRISHI: There you go. JOSH: Okay. HRISHI: You got anymore? JOSH: NO. HRISH: I'm sorry. Ricott-anymore? JOSH: Boom! [Intro Music] HRISHI: You're listening to The West Wing Weekly. My name is Hrishikesh Hirway. JOSH: And mine is Joshua Malina. HRISHI: Today we've got a special episode. It's the return of Big Block of Cheese Day. JOSH: Yeah, it's been a long time. Big Block of Cheese Day. In the spirit of Andrew Jackson, and I'd like to think probably the only thing we do in the spirit of Andrew Jackson HRISHI: That’s good, although you do give me a hard time and I'd like to think that it's in the spirit of Andrew Jackson that you terrorize an Indian. JOSH: [laughing] That's a perfect…I'm just going to leave it at that. I can't top that. Well done! [West Wing Episode 2.16 excerpt] DONNA: Andrew Jackson, while he was president had in the main foyer of The White House – I can’t believe I’m giving this speech – a two-tonne block of cheese. In that spirit, Leo McGarry designates one day for certain senior staff members to take appointments with people or groups that wouldn’t ordinarily be able to get the ear of The White House. [end excerpt] HRISHI: And we're going to jump right in with a Big Block of Cheese Day question about Big Block of Cheese Day. -

The Scarab Oklahoma City University’S Annual Anthology of Prose, Poetry, and Artwork

The Scarab Oklahoma City University’s Annual Anthology of Prose, Poetry, and Artwork 31st Edition Copyright © The Scarab 2013 All Rights Reserved 1 Editorial Staff Editor-in-Chief Caitlin Swisher Poetry Ashley Dougherty Fiction and Non-Fiction Jessica Garvey Jason Herrera Theresa Hottel Abigail Vestail Art and Photography Jessica Garvey Danielle Kutner Sponsor Dr. Terry Phelps The Scarab is published annually by the Oklahoma City University chapter of Sigma Tau Delta, the International English Honor Society. Opinions and beliefs expressed herein do not necessarily reflect those of the university, the chapter, or the editors. Submissions are accepted from students, faculty, staff, and alumni. Address all correspondence to The Scarab c/o Dr. Ter- ry Phelps, 2501 N. Blackwelder, Oklahoma City, OK 73106, or e-mail [email protected]. The Scarab is not responsible for returning submitted work. All submissions are subject to editing. 2 Table of Contents The Scarab 2013 Front Cover 55 Untitled By Jason Alexander Herrera Scarab Nouveau 60 100 By Jessica Garvey By Amanda Meyer Visual Art 62 Untitled 5 Catwalk By Brishti Bagshi By Amanda Meyer 69 Untitled 7 Root By Emma Foroutan By Amanda Meyer 71 Untitled 8 Moonlight By Danielle Kutner By Perla Carreon 77 Untitled 12 Unititled By Brishti Bagchi By Amanda Fryar 89 Transforming 13 Untitled By Micah McCoy By Jason Alexander Herrera 102 Gated Door 14 Roses By Amanda Meyer By Micah McCoy 104 Whimsical Playtime 15 Unititled By Amanda Gathright By Brishti Bagchi Poetry 16 Coeur et a la Maison1 6 A Study in Romanticism By Mollie Dysart By Dr. -

Vol. 32 No.23 Hearst on ~ Le Mercredi 22 Août 2007 1,25$ +

HA13 “L'éducation ne consiste pas à gaver, mais à DE HA14 À HA18 donner faim” Michel Tardy, HA5-HA6 ET HA19-HA20 sociologue 1976 - 2007 Le Nord LeLeVol. 32 No.23 NordNHearst On ~ Leo mercredi 22r août 2007d1,25$ + T.P.S. Succès pour le H.O.G. HA02 Le Festival d’été du centre-ville n’a pas connu le succès espéré en raison des sautes d’humeur de Dame Nature. Plusieurs activités ont dû être annulées mais cela n’a pas empêché ces jeunes de participer au concours «Sue’s Mini Pops» qui avait lieu jeudi dernier. Joanie Balle lente Gaudreault, Arianne Gaudreault, Hannah Sylvain, Michelle Gaudreault, Chloé Richard et Kayla Rodrigue figuraient parmi les par- ticipantes qui sont montées sur la scène en soirée. Photo disponible au journal Le Nord/CP HA22 Mercredi Jeudi Vendredi Samedi Dimanche Lundi Ensoleillé avec Possibilité d’orage Ensoleillé Ciel variable Ciel variable passages nuageux Faible pluie Max 16 Max 25 Min 15 Max 19 Min 17 Max 18 Min 9 Max 19 Min 8 Max 19 Min 12 PdP 60% PdP 0% PdP 20% PdP 20% PdP 10% PdP 90% Plusieurs centaines de personnes L’événement HOG de Hearst connaît un grand succès HEARST (FB) – Le 12e rassem- nes ont assisté à l’événement l’après-midi entre Hearst et ils ont grandement apprécié leur 1000$ de plus que l’an dernier. blement Hearst Hog a connu un samedi en fin d’après-midi et en Kapuskasing. Cette une hausse séjour, souligne M. Villeneuve. Deux personnes ont partagé le grand succès en fin de semaine.