Local 2.0 How Digital Technology Empowers Local Communities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kirklees Metropolitan Council

KIRKLEES COUNCIL (TRAFFIC REGULATION) (NO. 6) ORDER 2014 LOWERHOUSES LANE, LOWERHOUSES, NEWSOME, HUDDERSFIELD The Council of the Borough of Kirklees ("the Council") in exercise of their powers under Sections 1, 2, 4, 32, 35, 45, 46, 47, 49 and 53 of the Road Traffic Regulation Act 1984 ("the Act"), Part 6 of the Traffic Management Act 2004, the Road Traffic (Permitted Parking Area and Special Parking Area) (Metropolitan Borough of Kirklees) Order 2006 and of all other enabling powers and after consultation with the Chief Officer of Police in accordance with Part III of Schedule 9 to the Act hereby makes the following Order which relates to a road in the Newsome ward in the Kirklees Metropolitan District:- PART I 1. Interpretation 1.1. Except where the context otherwise requires any reference in this Order to a numbered Article is a reference to the Article bearing that number in this Order and any reference in this Order to a numbered Schedule is a reference to the Schedule bearing that number in this Order. 1.2. In this Order except where the context otherwise requires the following expressions have the meanings hereby respectively assigned to them:- “civil enforcement officer” has the meaning given by S.76 of the 2004 Act. “enforcement authority” means the Council. “penalty charge” has the meaning given by S.92 of the 2004 Act. “subordinate legislation” has the same meaning as in Section 21 of the Interpretation Act 1978. "telecommunications apparatus" has the same meaning as in the Telecommunications Act 1984. “the 2004 Act” means the Traffic Management Act 2004. -

The Rise and Fall of the Labour League of Youth

University of Huddersfield Repository Webb, Michelle The rise and fall of the Labour league of youth Original Citation Webb, Michelle (2007) The rise and fall of the Labour league of youth. Doctoral thesis, University of Huddersfield. This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/761/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ THE RISE AND FALL OF THE LABOUR LEAGUE OF YOUTH Michelle Webb A thesis submitted to the University of Huddersfield in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Huddersfield July 2007 The Rise and Fall of the Labour League of Youth Abstract This thesis charts the rise and fall of the Labour Party’s first and most enduring youth organisation, the Labour League of Youth. -

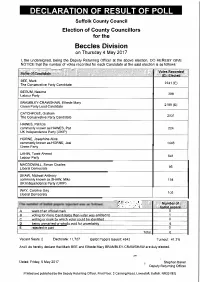

Waveney Declaration of Results 2017

DECLARATION OF RESULT OF POLL Suffolk County Council Election of County Councillors for the Beccles Division on Thursday 4 May 2017 I, the undersigned, being the Deputy Returning Officer at the above election, DO HEREBY GIVE NOTICE that the number of votes recorded for each Candidate at the said election is as follows: . .. ·... i xVot�i;Recorded ) . < ····•·•·••·· ··•·. ,. '. / 1 ·N�rii�b'fq�ndidat;:c.:: .',-·c:.'.'.\_",," --·--·> -._-_:.._·, . ;� ·: . ;/\<:. .� . \.. ·· < ; . " ... ·.• .· .·.·.. ···•·•••( > !El: Elected BEE, Mark The Conservative Party Candidate 2241 (E) BEGUM, Nasima Labour Party 388 BRAMBLEY-CRAWSHAW, Elfrede Mary Green PartyLead Candidate 2189(E) CATCHPOLE, Graham The Conservative Party Candidate 2031 HAWES, Patricia commonly known as HAWES, Pat 224 UK Independence Party (UKIP) HORNE, Josephine Alice commonly known as HORNE, Josi 1446 Green Party LAHIN, Tarek Ahmed Labour Party 541 MACDOWALL, Simon Charles Liberal Democrats 96 SHAW, Michael Anthony commonly known as SHAW, Mike 194 UK Independence Party (UKIP) WAY, Caroline Gay Liberal Democrats 105 · c: ,. · Number.(of." . · .. /baUofi:iatif!I'.$··•·•·• A want of an official mark B voting for more Candidates than voter was entitled to C writing or mark bv which voter could be identified D being unmarked or whollv void for uncertainty 5 E reiected in part Total 6 Vacant Seats: 2 Electorate: 11,727 Ballot Papers Issued: 4843 Turnout: 41.3% And I do hereby declare that Mark BEE and Elfrede Mary BRAMBLEY-CRAWSHAW are duly elected. Dated: Friday, 5 May 2017 Stephen Baker -

Local Elections Postponed

The newsletter of your Newsome Ward Green Party councillors NEWSOME WARD SPECIAL CORONAVIRUS DIGITAL GREEN NEWS EDITION PLEASE SHARE! Covering Armitage Bridge, Ashenhurst, Aspley, Berry Brow,e Newsome, Lockwood, Longroyd Bridge, Lowerhouses, Primrose Hill, Rashcliffe, Springwood, Taylor Hill, Town Centre OUR FIRST DIGITAL NEWSLETTER To protect our local leafleters, and stop the spread of the virus we have decided to suspend our regular newsletter deliveries. To help you keep up to date with what we are doing we have launched our first eNewsletter! Please share it widely among people you know in the Newsome Ward either by Email, Facebook, WhatsApp or Twitter. We want to keep in touch with as many KIRKLEES COUNCILLORS COME people as possible. If you want to be added to our TOGETHER DURING CRISIS newsletter mailing list please email [email protected] Councillors from across the political spectrum come together with your name address and email to ensure council is still able to provide key services address. The coronavirus crisis means Councillor Andrew Cooper as leader Kirklees Council is having to of the Green Party group on Kirklees LOCAL ELECTIONS maintain many essential services Council is represented on the group: like bin collections, adult and “It is inspiring to see political POSTPONED children’s social care, schools for differences being put aside for the the children of key workers and common good Local elections for Kirklees Council vulnerable children. “It would be good to see this sort of will be postponed for a year to positive working together continue While many Council meetings have May 2021 due to the coronavirus beyond this crisis. -

Candidates North West Region

Page | 1 LIBERAL/LIBERAL DEMOCRAT CANDIDATES IN THE NORTH WEST REGION 1945-2015 Constituencies in the counties of Cheshire, Cumbria and Lancashire INCLUDING SDP CANDIDATES in the GENERAL ELECTIONS of 1983 and 1987 PREFACE The North West Region was a barren area for the Liberal/Liberal Democratic Party for decades with a higher than average number of constituencies left unfought after the 1920s in many cases. After a brief revival in 1950, in common with most regions in the UK, when the party widened the front considerably, there ensued a further bleak period until the 1970s. In 1983-87, as with other regions, approximately half the constituencies were fought by the SDP as partners in the Alliance. 30 or more candidates listed have fought elections in constituencies in other regions, one in as many as five. Cross-checking of these individuals has taken time but otherwise the compilation of this regional Index has been relatively straight forward compared with others. Special note has been made of the commendable achievements of ‘pioneer’ candidates who courageously carried the fight into the vast swathe of Labour-held constituencies across the industrial zone of the region beginning in the 1970s. The North West Region has produced its fair share of personalities who have flourished in fields outside parliamentary politics. Particularly notable are the candidates, some of whom were briefly MPs, whose long careers began just after World War I and who remained active as candidates until after World War II. (Note; there were four two-member constituencies in Lancashire, and one in Cheshire, at the 1945 General Election, denoted ‘n’ after the date. -

“OFF YER BIKE!” Lockdown Restrictions Are Slowly Easing and Huddersfield Town Police Seize Trail Bikes and Quad Bikes Following Joint Centre Is Slowly Opening Up

The newsletter of your Newsome Ward Green Party councillors OUR SECOND NEWSOME WARD DIGITAL NEWSLETTER We are aware that there are still risks from the coronavirus so we have decided to produce another E-newsletter. GREEN NEWS Please share on your own Facebook Covering Armitage Bridge, Ashenhurst, Aspley, Berry Brow,e Newsome, Lockwood, Longroyd Bridge, and twitter sites and send to people Lowerhouses, Primrose Hill, Rashcliffe, Springwood, Taylor Hill, Town Centre you know who live in the Newsome Ward. We would really appreciate it. TOWN CENTRE SLOWLY REOPENS Councillors Andrew Cooper at Cafe Evolution’s ‘magic window” “OFF YER BIKE!” Lockdown restrictions are slowly easing and Huddersfield Town Police seize trail bikes and quad bikes following joint Centre is slowly opening up. working with the community and local Councillors. Councillors Andrew Cooper and Following a joint initiative by to the crusher. Karen Allison inspected the new one West Yorkshire Police and Councillor Andrew Cooper said: way system for pedestrians on New Newsome Ward Councillors a “We’re obviously pleased about this Street and the widened space for pedestrians on several roads. number of illegal trail bikes and but realise that there will be other quad bikes have been seized. bikes out there that are being used Andrew said, “I have asked if direction indicators can be put on eye level and Riders of these bikes frequently use illegally. “I’d like to thank all the local people also asked the Council to consider them without helmets are uninsured how the measures have impacted and ride on footpaths and fields in the who kept us informed and we will do all we can to get these bikes seized, on disabled people who have lost area causing noise and disturbance. -

Local Election Results 2008

Local Election Results May 2008 Andrew Teale August 15, 2016 2 LOCAL ELECTION RESULTS 2008 Typeset by LATEX Compilation and design © Andrew Teale, 2012. Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.3 or any later version published by the Free Software Foundation; with no Invariant Sections, no Front-Cover Texts, and no Back-Cover Texts. A copy of the license is included in the section entitled “GNU Free Documentation License”. This file, together with its LATEX source code, is available for download from http://www.andrewteale.me.uk/leap/ Please advise the author of any corrections which need to be made by email: [email protected] Contents Introduction and Abbreviations9 I Greater London Authority 11 1 Mayor of London 12 2 Greater London Assembly Constituency Results 13 3 Greater London Assembly List Results 16 II Metropolitan Boroughs 19 4 Greater Manchester 20 4.1 Bolton.................................. 20 4.2 Bury.................................... 21 4.3 Manchester............................... 23 4.4 Oldham................................. 25 4.5 Rochdale................................ 27 4.6 Salford................................. 28 4.7 Stockport................................ 29 4.8 Tameside................................. 31 4.9 Trafford................................. 32 4.10 Wigan.................................. 34 5 Merseyside 36 5.1 Knowsley................................ 36 5.2 Liverpool................................ 37 5.3 Sefton.................................. 39 5.4 St Helens................................. 41 5.5 Wirral.................................. 43 6 South Yorkshire 45 6.1 Barnsley................................ 45 6.2 Doncaster............................... 47 6.3 Rotherham............................... 48 6.4 Sheffield................................ 50 3 4 LOCAL ELECTION RESULTS 2008 7 Tyne and Wear 53 7.1 Gateshead............................... 53 7.2 Newcastle upon Tyne........................ -

University of Huddersfield Repository

University of Huddersfield Repository Perks, R.B. The new Liberalism and the challenge of Labour in the West Riding of Yorkshire 1885-1914 with special reference to Huddersfield Original Citation Perks, R.B. (1985) The new Liberalism and the challenge of Labour in the West Riding of Yorkshire 1885-1914 with special reference to Huddersfield. Doctoral thesis, Huddersfield Polytechnic. This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/4598/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ 343 VOI_UP1 E TWO CHAPTER FIVE WAR, LIBERALISM AND LABOUR REVIVAL, 1899-1905 1. The Khaki Election and the Impact of the Boer War in Huddersfield, 1899-1902 345 2. Conservatism Versus Liberalism: Local Politics and National Issues, 1902-5 . 362 3. The Revival of LaLuuI: .lotadlism and the Conversion of the Trades Council, 1900-1905 382 4. -

Revised Proposals for New Constituency Boundaries in Yorkshire and the Humber Contents

Revised proposals for new constituency boundaries in Yorkshire and the Humber Contents Summary 3 1 What is the Boundary Commission for England? 5 2 Background to the 2018 Review 7 3 Revised proposals for Yorkshire and the Humber 13 The sub-region split 15 Humberside 17 North Yorkshire 22 South Yorkshire and West Yorkshire 25 4 How to have your say 53 Annex A: Revised proposals for constituencies, 55 including wards and electorates Revised proposals for new constituency boundaries in Yorkshire and the Humber 1 Summary Who we are and what we do out our analysis of all the responses to our initial proposals in the first and second The Boundary Commission for England consultations, and the conclusions we is an independent and impartial have reached as to how those proposals non-departmental public body, which is should be revised as a result. The annex responsible for reviewing Parliamentary to each report contains details of the constituency boundaries in England. composition of each constituency in our revised proposals for the relevant region: The 2018 Review maps to illustrate these constituencies can be viewed on our website or in hard copy We have the task of periodically reviewing at a local place of deposit near you. the boundaries of all the Parliamentary constituencies in England. We are What are the revised proposals currently conducting a review on the basis for Yorkshire and the Humber? of new rules laid down by Parliament. These rules involve a significant reduction We have revised the composition of in the number of constituencies in 31 of the 50 constituencies we proposed England (from 533 to 501), resulting in in September 2016. -

Electoral Performance of the British National Party in the UK

Electoral performance of the British National Party in the UK Standard Note: SN/SG/5064 Last updated: 15 May 2009 Author: Edmund Tetteh Social and General Statistics This note provides data on the electoral performance of the British National Party (BNP) in local and parliamentary elections. This note has been updated to include results from the local elections held in England on 1 May 2008. It also comments upon results from various elections up to 2008. As at May 2009, the BNP had 55 councillors in local government in England. See also Library Research Papers 08/48 Local Elections 2008 08/12 Election Statistics: UK 1918-2007 08/47 London Elections 2008. Elections for Mayor of London and London Assembly Contents 1 Background 3 2 Electoral performance 3 2.1 General Elections 3 1992 General Election 3 1997 General Election 3 2001 General Election 4 2005 General Election 4 2.2 Local authority elections 4 2000 5 2001 5 2002 5 2003 5 2004 5 2005 6 Standard Notes are compiled for the benefit of Members of Parliament and their personal staff. Authors are available to discuss the contents of these papers with Members and their staff but cannot advise others. 2006 6 2007 6 2008 6 2009 8 2.3 Mayor of London and London Assembly 8 2.4 European Parliament elections 9 3 Ward-by-ward BNP electoral data for 2008 local election 11 4 Appendix: Calculation of Vote Shares in Multi-Member Wards 19 2 1 Background The BNP, UK’s largest extreme-right political party, was founded in 1982 through the merger of the New National Front and a faction of the British Movement. -

'We Have Come a Long Way': the Labour Party and Ethnicity in West Yorkshire

University of Huddersfield Repository Ward, Paul 'We have come a long way': the Labour Party and ethnicity in West Yorkshire Original Citation Ward, Paul (2007) 'We have come a long way': the Labour Party and ethnicity in West Yorkshire. In: Sons and daughters of labour: a history and recollection of the Labour Party within the historic boundaries of the West Riding of Yorkshire. University of Huddersfield Press, Huddersfield, pp. 157-170. ISBN 186218058X This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/896/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ We have come a long way: The Labour Party and Ethnicity in West Yorkshire Paul Ward This is a pre-print version of an essay published in Sons and daughters of labour: a history and recollection of the Labour Party within the historic boundaries of the West Riding of Yorkshire. -

Annual Council 17 May 2012 Agenda

THE RUGBY BOROUGH COUNCIL You are hereby summoned to attend the ANNUAL MEETING of the Rugby Borough Council, which will be held in the TOWN HALL, RUGBY, on Thursday 17th May 2012 at 11.00 am. A G E N D A PART 1 – PUBLIC BUSINESS 1. Apologies for absence. 2. To elect a Mayor for the ensuing year. (Following this the Mayor will make a declaration of acceptance of office). 3. To appoint a Deputy Mayor for the ensuing year. (Following this the Deputy Mayor will make a declaration of acceptance of office). 4. Vote of thanks to the retiring Mayor. 5. Vote of thanks to retiring Councillors 6. Mayor’s announcements. 7. To receive the report of the Returning Officer on the Rugby Borough Council Election on 3rd May 2012. 8. Constitutional Arrangements and Allocation of Seats to Party Groups 2012/13. To receive and consider the report of the Executive Director. 9. Appointments to Outside Bodies 2012/13 – By Virtue of Office and Miscellaneous Appointments. To receive and consider the report of the Executive Director. PART 2 – EXEMPT INFORMATION There is no business involving exempt information. DATED THIS 9th day of May 2012 Executive Director To: The Mayor and Members of Rugby Borough Council Election of Councillors Agenda item 7 for the Wards of Rugby Borough Council Summary of Results Date of Election : Thursday 03 May 2012 Contested Elections Admirals & Cawston Name of Candidate Description (if any) Number of Votes ALLANACH Richard John Liberal Democrats 100 BIRKETT Steven William Labour Party Candidate 641 BUTLIN Peter James The Conservative