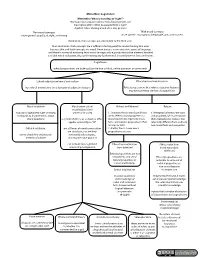

Supporting Material for Chapter 5, Meta Ethics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Noncognitivism and Autonomy Eamonn Callan

Document generated on 09/23/2021 5:34 p.m. Philosophical Inquiry in Education Noncognitivism and Autonomy Eamonn Callan Volume 23, Number 2, 2016 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1070470ar DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1070470ar See table of contents Publisher(s) Canadian Philosophy of Education Society ISSN 2369-8659 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this document Callan, E. (2016). Noncognitivism and Autonomy. Philosophical Inquiry in Education, 23(2). https://doi.org/10.7202/1070470ar Copyright ©, 2016 Eamonn Callan This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ Noncognitivism and Autonomy Eamonn Callan, University of Alberta The supposed failure of ethical cognitivism is the beginning of one com mon argument for the ideal of personal autonomy and its supporting social practices. The argument can be summarized as follows. There is no ethical knowledge that could conceivably be available to us, or at least all current claims to such knowledge are doubtful to a degree that makes them untenable. Therefore, experts to whose authority we should defer regarding ethical deci sions simply do not exist. That is tantamount to saying we should act autonomously in making ethical decisions and, if we are to grant the capacity and liberty to make such decisions to others, we need to develop educational and other social practices that nurture the relevant capacity and bestow the necessary liberty. -

The Theory of Justice

Syllabus of the course: The Theory of Justice Утверждена Академическим советом ООП Протокол № 1от «31» августа 2018 г. Pre-requisites This course is based on knowledge and competences which were provided by the following disciplines: ● History of Philosophy ● General Ethics ● Analytic Ethics ● Political Philosophy ● Political Science Course Type: Elective Learning Objectives The objective of the course make the students familiar with the major contemporary theories of justice and the development of the necessary analytic skills of evaluation of any normative conception of justice as well as the capacity to participate in the public discourse on justice, which is about to emerge. Course Plan Ethics, Morality, Justice Language, Logic and Meaning of Justice Utilitarian Theory of Justice The Theory of Justice of John Rawls The Justice of Political Liberalism Libertarian Theory of Justice by Robert Nozick Justice by Agreement by David Gauthier Marxism as a Theory of Justice Feminism and Justice Communitarian Critique of Justice Just War Theory The Russian Historical Discourse of Justice 1. Ethics, Morality, Justice Ethics. The meaning of Ethics and Morality. Ethical Theory, General Ethics and Individual Ethics. The History of Morality. The Sociology of Morality. The Psychology of Morality. The stages of moral growth. Moralism, Immoralism, Amoralism. Human nature. Ethical skepticism. Metaethics. Theories of Metaethics. Naturalism. Emotivism. Universal Prescriptivism. Intuitivism. The nature of moral concepts. Good and Evil. Moral Relativism. Sentimentalism. Normative Morals. Moral Theory. Egoism. Psychological Egoism. Religious Ethics. Convention. Particularism. Teleological Ethics. Consequentialism. Utilitarianism. Hedonism. Deontology. Kant’s categorical imperative. Virtue Ethics. Morality and Rationality. Negative versus Politive Rights and Duties. Elitism. Applied Ethics. -

Ethical Realism/Moral Realism Ethical Propositions That Refer to Objective Features May Be True If They Are Free of Subjectivis

Metaethics: Cognitivism Metaethics: What is morality, or “right”? Normative (prescriptive) ethics: How should people act? Descriptive ethics: What do people think is right? Applied ethics: Putting moral ideas into practice Thin moral concepts Thick moral concepts more general: good, bad, right, and wrong more specic: courageous, inequitable, just, or dishonest Centralism- thin concepts are antecedent to the thick ones Non-centralism- thick concepts are a sucient starting point for understanding thin ones because thin and thick concepts are equal. Normativity is a non-excisable aspect of language and there is no way of analyzing thick moral concepts into a purely descriptive element attached to a thin moral evaluation, thus undermining any fundamental division between facts and norms. Cognitivism ethical propositions are truth-apt (can be true or false), unlike questions or commands Ethical subjectivism/moral anti-realism Ethical realism/moral realism True ethical propositions are a function of subjective features Ethical propositions that refer to objective features may be true if they are free of subjectivism Moral relativism Moral universalism/ Robust and Minimal Robust moral objectivism/ nobody is objectively right or wrong universal morality 1. Semantic thesis: moral predicates 3. Metaphysical thesis: the facts in regards to diagreements about are to refer to moral properties so and properties of #1 are robust-- moral questions a system of ethics, or a universal ethic, moral statements represent moral their metaphysical status is not applies universally to "all" facts, and express propositions that relevantly dierent from ordinary are true or false non-moral facts and properties Cultural relativism not all forms of moral universalism 2. -

Truth: in Ethics and Elsewhere

ANALYTIC TEACHING Vol. 19, No 1 Truth: In Ethics and Elsewhere This paper was presented at the North American Association for Community of Inquiry (NAACI) conference held in La Crosse, Wisconsin, USA, in July, 1998. Susan T. Garder All truths wait in all things, They neither hasten their own discovery nor resist it .... Walt Whitman, «Song of Myself» THE SEDUCTION OF RELATIVITY t is popular to make the claim, particularly when it comes to questions of value, that there is no I such thing as «truth.» For some, a belief in social or cultural relativism is the source of such scepticism. Such individuals would argue that it is chauvinistic arrogance to believe that just because, from one’s own point of view, practices carried out by other cultures appear to be immoral, e.g., cliterodectomies on unwilling young women, that somehow they are immoral per se. Others would argue for an even more radical form of relativism, no doubt stemming from a misguided view of equal- ity, namely that any individual viewpoint is a good (or bad) as anyone else’s: «from my point of view `x’ is immoral, but I wouldn’t dream of saddling anyone else with my morals.» Still others believe that, despite the drawbacks of a relativistic position, they must nonetheless remain sceptical about the possi- bility of truth in ethics in order to distance themselves from those who have inflicted enormous harm on others in the name of having a privileged access to truth. The Spanish inquisition, the holocaust, the decimation of indigenous people, were all carried out by individuals most of whom believed that they had truth on their side. -

Eritis Sicut Deus: Moral Theory and the Sin of Pride

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Asbury Theological Seminary Faith and Philosophy: Journal of the Society of Christian Philosophers Volume 3 Issue 4 Article 4 10-1-1986 Eritis Sicut Deus: Moral Theory and the Sin of Pride Gilbert Meilaender Follow this and additional works at: https://place.asburyseminary.edu/faithandphilosophy Recommended Citation Meilaender, Gilbert (1986) "Eritis Sicut Deus: Moral Theory and the Sin of Pride," Faith and Philosophy: Journal of the Society of Christian Philosophers: Vol. 3 : Iss. 4 , Article 4. Available at: https://place.asburyseminary.edu/faithandphilosophy/vol3/iss4/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at ePLACE: preserving, learning, and creative exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faith and Philosophy: Journal of the Society of Christian Philosophers by an authorized editor of ePLACE: preserving, learning, and creative exchange. ERITIS SICUT DEUS: MORAL THEORY AND THE SIN OF PRIDE Gilbert Meilaender The fundamental temptation, especially for those who are serious about the moral life, is always the same: failing in trust, to want to be like God, knowing good and evil. "What the serpent has in mind," Karl Barth has written, "is the establishment of ethics. "1 This is an overstatement, but it points us toward an important truth. The number of possible moral theories is not large, though their varieties are infinitely complex. C. S. Lewis has a simple illustration which directs attention to the features of life that any moral theory must consider. Think of us as a fleet of ships sailing in formation. -

Essays on Ethical Universalizability

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications - Department of Philosophy Philosophy, Department of 1985 Introduction from Morality and Universality: Essays on Ethical Universalizability Nelson T. Potter University of Nebraska - Lincoln, [email protected] Mark Timmons University of Illinois Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/philosfacpub Part of the Continental Philosophy Commons, and the Ethics and Political Philosophy Commons Potter, Nelson T. and Timmons, Mark, "Introduction from Morality and Universality: Essays on Ethical Universalizability" (1985). Faculty Publications - Department of Philosophy. 23. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/philosfacpub/23 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Philosophy, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications - Department of Philosophy by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Potter & Timmons in Nelson Potter and Mark Timmons (editors), Morality and Universality, ix-xxxii. Copyright 1985, D. Reidel Publishing. Used by permission. INTRODUCTION In the past 25 years or so, the issue of ethical universalizability has figured prominently in theoretical as well as practical ethics. The term, ‘universalizability’ used in connection with ethical considerations, was apparently first introduced in the mid-1950s by R. M. Hare to refer to what he characterized as a logical thesis -

Justification and Moral Cognitivism

Department of Theology Spring Term 2018 Master's Thesis in Human Rights 30 ECTS Justification and Moral Cognitivism An Analysis of Jürgen Habermas’s Metaethics Author: Johan Elfström Supervisor: Professor Elena Namli Abstract In this thesis, I scrutinise and interpret Jürgen Habermas’s claim that justification of moral norms necessitates cognitivism. I do this by analysing the general idea behind his discourse theory of morality and then his metaethics. From there, I examine the non-cognitivist theory called prescriptivism as set out by Richard Hare to see if his account of moral reasoning is able to counter Habermas’s claims and thereafter, I examine some criticism against his concept of communicative action. I also engage with the discussion on how to define cognitivism: that is, whether the line should be drawn between moral realism on the cognitivist side, and constructivism on the other, or if cognitivism can include constructivist theories too. I propose that it should, provided that it allows moral statements to be truth-apt and express a mental state like that of belief. Following this definition, I argue that Habermas can be labelled a cognitivist and finally, I conclude that Habermas argument does not hold under scrutiny. Table of Contents 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 1 1.1. Cognitivism and Rational Justification ........................................................................... 2 1.2. Previous Research .......................................................................................................... -

Pragmatism and Effective Altruism: an Essay on Epistemology and Practical Ethics John Aggrey Odera University of Pennsylvania

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Penn Humanities Forum Undergraduate Research Undergraduate Humanities Forum 2018-2019: Stuff Fellows 5-2019 Pragmatism and Effective Altruism: An Essay on Epistemology and Practical Ethics John Aggrey Odera University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/uhf_2019 Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Odera, John Aggrey, "Pragmatism and Effective Altruism: An Essay on Epistemology and Practical Ethics" (2019). Undergraduate Humanities Forum 2018-2019: Stuff. 2. https://repository.upenn.edu/uhf_2019/2 This paper was part of the 2018-2019 Penn Humanities Forum on Stuff. Find out more at http://wolfhumanities.upenn.edu/annual-topics/stuff. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/uhf_2019/2 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Pragmatism and Effective Altruism: An Essay on Epistemology and Practical Ethics Abstract This paper hopes to provide an American Pragmatist reading of the Effective Altruism philosophy and movement. The criticism levied against Effective Altruism here begins from one of its founding principles, and extends to practical aspects of the movement. The utilitarian leaders of Effective Altruism consider Sidgwick’s ‘point of view of the universe’ an objective starting point of determining ethics. Using Quality Adjusted Life Years (QALYs), a popular measure in contemporary welfare economics, they provide a “universal currency for misery” for evaluating decisions. Through this method, one can calculate exactly the value of each moral decision by identifying which one yields more QALYs, and, apparently, objectively come to a conclusion about the moral worth of seemingly unrelated situations, for example, whether it is more moral to donate money so as to help women suffering from painful childbirth-induced fistulas, or to donate to starving children in famine-ridden areas. -

Critical Moral Thinking Or Refinement of Disposition? What Is the Aim of Moral Education?*

Epistrophè Revue d’Éthique Professionnelle en Philosophie et en Éducation. Études et Pratiques Journal of Professional Ethics in Philosophy and Education. Studies and Practices [EPREPE] vol. 2, 2018-2019 http://eprepe.pse.aegean.gr/ ISSN: 1234-5678-9000 Critical moral thinking or refinement of disposition? What is the aim of moral education?* Raisonnement moral critique ou raffinement de la disposition? Qui est le but de l’éducation morale? Eleni Kalokairinou Department of Philosophy and Education Aristotle University of Thessaloniki In the present paper I examine the possibility of moral Dans cet article, J’examine la possibilité de l’éducation education. It is pointed out that, even though religion is morale. Je souligne que, quoique la religion est officially taught in primary and secondary education, this is officiellement enseignée à l’éducation primaire et not the case with ethics and moral education. I then secondaire, la situation est complètement différente avec explore the kind of moral education we should offer the l’éthique et l’éducation morale. Le but de mon article est youth in the likely event that ethics is officially introduced d’explorer le genre de l’éducation morale que nous in primary and secondary education. We examine R.M. devrons offrir aux jeunes personnes dans le cas où Hare’s claim that moral education involves teaching the l’éthique est officiellement introduite à l’éducation young men the moral language and moral thinking and primaire et secondaire. J’examine la thèse que R. M. Hare reasoning, and we find his suggestion lacking in certain soutient que l’éducation morale contient l’enseignement important respects. -

Intuition and Security in Moral Philosophy

Michigan Law Review Volume 82 Issue 4 1984 Intuition and Security in Moral Philosophy Stephen R. Munzer University of California, Los Angeles Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr Part of the Law and Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Stephen R. Munzer, Intuition and Security in Moral Philosophy, 82 MICH. L. REV. 740 (1984). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr/vol82/iss4/11 This Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Michigan Law Review at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INTUITION AND SECURITY IN MORAL PHILOSOPHYt Stephen R. Munzer* MORAL THINKING: ITS LEVELS, METHOD, AND POINT. By R.M. Hare. Oxford: Clarendon Press. 1981. Pp. viii, 242. Cloth, $22.50; paper, $8.95. I. UNIVERSAL PRESCRIPTIVISM AND UTILITARIANISM In Moral Thinking Professor R.M. Hare refines and extends a metaethical theory that he began to develop over thirty years ago. 1 The theory is universal prescriptivism. It holds that moral judg ments are universalizable, prescribe rather than either describe facts or merely express feelings, and override other kinds of judgments, such as aesthetic or prudential judgments, in cases of conflict. In his new book Hare discusses how to think about moral problems and tries to show why sound thinking about them leads to utilitarianism. The book is self-contained and therefore accessible to the reader un acquainted with Hare's earlier works. -

EXPRESSIVE FICTIONALISM By

EXPRESSIVE FICTIONALISM by SIMON LOWE A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Philosophy College of Arts and Laws The University of Birmingham January 2018 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT In this thesis I will present a theoretical, non-realist account of moral language which I call ‘Expressive Fictionalism’. Expressive Fictionalism is a combined approach involving semantic content based on Joycean revisionary fictionalism and pragmatic expressivism with influences of projectivism and the quasi-realism of Simon Blackburn. The result is a marriage between the two which ultimately works towards mutual advantage. The aim of this thesis is to provide a non-realist account of moral language in the form of expressive fictionalism, which, I posit, can explain a form of moral communication, on both a semantic and a pragmatic level, without compromising its own non-realism in the process, which avoids issues which are associated with the Frege-Geach problem and which is a non- error theoretic account of moral discourse. My methodology is a combination of semantics, pragmatics, thought experiment with some influences of empiricism, references to modern studies in behavioural & cognitive psychology as well as historical analogy. -

Unit 14 Prescriptivism: R. M. Hare*

Meta-Ethics UNIT 14 PRESCRIPTIVISM: R. M. HARE* Structure 14.0 Objectives 14.1 Introduction 14.2 Definition 14.3 The Significance of Prescriptivism in Moral Philosophy 14.4 Philosophical Views 14.5 Let Us Sum Up 14.6 Key Words 14.7 Further Readings and References 14.8 Answers to Check Your Progress 14.0 OBJECTIVES The aim of this unit is, To explain Hare’s moral/ethical position about prescriptivism. To provide an explanation about the role of prescriptivism in moral and ethical philosophy in general and the basic questions about the moral/ethical in particular. 14.1 INTRODUCTION We can trace the seeds of prescriptivism in the philosophy of Socrates, Aristotle, Hume, Kant and Mill, but the main proponent of this meta-ethical theory was philosopher Richard Mervyn Hare (1919-2002). Through the analysis of moral discourse, Hare justified the preferences for utilitarianism. Hare served Royal Artillery in the Second World War and he was seized as a prisoner by Japan. This experience of second world war influenced Hare’s life and philosophy, particularly his view that moral philosophy is obligatory in nature and helps people to be a moral being (King: 2004). In moral philosophy, philosophers give their opinion/thought about moral problems and moral judgments and in this way everyone has their freedom to give their opinions. But according to Hare, the problem with this line of thought is that there is a lack of concern for others and rational thought is not put to use while formulating moral judgements. Hence the forementioned philosophers are considered as subjectivist or emotivists.