United Nations Peace Keeping Operations: Some Personal Reflections

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Library Catalogue

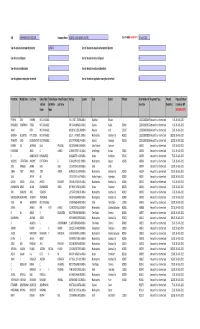

Id Access No Title Author Category Publisher Year 1 9277 Jawaharlal Nehru. An autobiography J. Nehru Autobiography, Nehru Indraprastha Press 1988 historical, Indian history, reference, Indian 2 587 India from Curzon to Nehru and after Durga Das Rupa & Co. 1977 independence historical, Indian history, reference, Indian 3 605 India from Curzon to Nehru and after Durga Das Rupa & Co. 1977 independence 4 3633 Jawaharlal Nehru. Rebel and Stateman B. R. Nanda Biography, Nehru, Historical Oxford University Press 1995 5 4420 Jawaharlal Nehru. A Communicator and Democratic Leader A. K. Damodaran Biography, Nehru, Historical Radiant Publlishers 1997 Indira Gandhi, 6 711 The Spirit of India. Vol 2 Biography, Nehru, Historical, Gandhi Asia Publishing House 1975 Abhinandan Granth Ministry of Information and 8 454 Builders of Modern India. Gopal Krishna Gokhale T.R. Deogirikar Biography 1964 Broadcasting Ministry of Information and 9 455 Builders of Modern India. Rajendra Prasad Kali Kinkar Data Biography, Prasad 1970 Broadcasting Ministry of Information and 10 456 Builders of Modern India. P.S.Sivaswami Aiyer K. Chandrasekharan Biography, Sivaswami, Aiyer 1969 Broadcasting Ministry of Information and 11 950 Speeches of Presidente V.V. Giri. Vol 2 V.V. Giri poitical, Biography, V.V. Giri, speeches 1977 Broadcasting Ministry of Information and 12 951 Speeches of President Rajendra Prasad Vol. 1 Rajendra Prasad Political, Biography, Rajendra Prasad 1973 Broadcasting Eminent Parliamentarians Monograph Series. 01 - Dr. Ram Manohar 13 2671 Biography, Manohar Lohia Lok Sabha 1990 Lohia Eminent Parliamentarians Monograph Series. 02 - Dr. Lanka 14 2672 Biography, Lanka Sunbdaram Lok Sabha 1990 Sunbdaram Eminent Parliamentarians Monograph Series. 04 - Pandit Nilakantha 15 2674 Biography, Nilakantha Lok Sabha 1990 Das Eminent Parliamentarians Monograph Series. -

NEET-2016-Honorable-Supreme

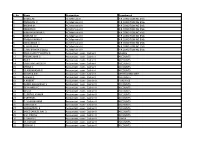

All India ROLL APPNO CNAME FNAME Rank 1 61006480 7300516 HET SHAH SANJAYKUMAR SHAH 2 60814976 7101292 EKANSH GOYAL SANJAY GOYAL 3 64008387 7107264 NIKHIL BAJIYA BHANWAR SINGH BAJIYA 4 61105682 7029377 ASHANK KHAITAN ANURAG KHAITAN 5 60504189 7113232 ARUSHI JASPAL RAM 6 61104349 7136495 DYUTI SHAH DURLABH SHAH BISHNOI 7 60510525 7025885 JAPNOOR KAUR MANMEET SINGH 8 65007312 7000142 DHRITIMAN CHATTERJEE SUPRIYO CHATTERJEE 9 61102675 7273463 AMIT KUMAR RATTAN LAL 10 64005180 7103882 UTKARSH ANAND MANOJ KUMAR SINHA 11 60828184 7056545 BALAJI DATTATRAYA SHUKLA SHATRUGHNA SHUKLA 12 60835453 7145776 PRAKHAR BANSAL AJAY BANSAL 13 64202454 7040682 PATEL LAJJA BEN JAYESH KUMAR PATEL JAYESH KUMARLAXMAN BHAI 14 60505421 7041203 TOSHALI PANDEY AWADHESH KUMAR PANDEY 15 60505074 7014382 GURASIS SINGH BOPARAI JAGWANT SINGH 16 60516344 7011909 TANISH MODI MANISH MODI 17 64903025 7197955 PRIYAZ MISHRA RAM RAJIV MISHRA 18 60416707 7193284 SWETANK ANAND BIRENDRA KUMAR 19 64104501 7107997 MAHAK KUMAR SURANA MAHENDRA KUMAR SURANA 20 64207759 7215659 PRACHI SINGH VINOY KUMAR SINGH 21 64714228 7147645 SHREYA MITTAL PAVAN KUMAR MITTAL 22 61103254 7081544 VISHAL SAINI SURENDER SINGH 23 64000996 7264260 AYUSH JAIN RAKESH KUMAR JAIN 24 60821877 7135524 AKHIL GUPTA MANOJ GUPTA 25 60835360 7046576 NIPUN SINGHAL NEERAJ SINGHAL 26 61905278 7179612 SIDDARTH V RAJ VARADARAJ V 27 64000872 7104550 SHUBHAM LEKHWANI OM PRAKASH LEKHWANI 28 60500574 7166230 SUKRITI CHAUDHRI SANDEEP CHAUDHRI 29 60511876 7031466 LOVISH GUPTA ARVIND KUMAR 30 60826866 7147125 AISHVARY GUPTA BRIJESH -

India Celebrates 70Th Republic

We Wish Readers a Happy Republic Day of India EVER TRUTHFUL # 1 Indian American Weekly: Since 2006 VOL 13 ISSUE 04 ● NEW YORK / DALLAS ● JANUARY 25 - 31, 2019 ● ENQUIRIES: 646-247-9458 www.theindianpanorama.news 15th Edition of Pravasi Bharatiya India celebrates 70th Republic Day Divas Concludes page 3 ● South African President Cyril Ramaphosa attends as Chief Guest ● Impressive Parade and enthusiasm mark the celebration Federal Government Shutdown ● Ends after a 35 -day Stand off PM lays a wreath at Amar Jawan Jyoti and pays tribute to martyrs NEW DELHI (TIP): Celebrations for the Trump Signs Bill Reopening Government 70th Republic Day began on Saturday, January for 3 Weeks through February 15 26, with South African President Cyril Ramaphosa in attendance as the chief guest, President Trump amid heavy security deployment in the city. announcing that "we have reached a deal Prime Minister Narendra Modi paid his to end the tributes to the martyrs by laying a wreath at shutdown." He has Amar Jawan Jyoti in the presence of Defense since signed a bill Minister Nirmala Sitharaman and the three which will keep service chiefs. Later Modi, wearing his government open traditional kurta-pajama and trademark through February 15 Nehru jacket, reached the Rajpath and received and greeted President Ram Nath Kovind and WASHINGTON (TIP): The House and Senate both the chief guest. contd on Page 38 approved a measure Friday, January 25 to temporarily reopen the federal government with a short-term Prime Minister Modi greets Chief Guest South spending bill that does not include President Donald African President Cyril Ramaphosa at Rajpath contd on Page 38 Photo / courtesy PIB Dr. -

CIN Company Name

CINL99999MH1962PLC012538 Company Name BOROSIL GLASS WORKS LIMITED Date Of AGM(DD‐MON‐YYYY) 09‐AUG‐2012 Sum of unpaid and unclaimed dividend 3456444 Sum of interest on unpaid and unclaimed dividend 0 Sum of matured deposit 0 Sum of interest on matured deposit 0 Sum of matured debentures 0 Sum of interest on matured debentures 0 Sum of application money due for refund 0 Sum of interest on application money due for refund 0 First Name Middle Name Last Name Father/Husb Father/Husba Father/Husband Address Country State District PINCode Folio Number of Investment Type Amount Proposed Date of and First nd Middle Last Name Securities Due(in Rs.) transfer to IEPF Name Name (DD‐MON‐YYYY) PUSHPA DEVI SHARMA NOT AVAILABLE VILL ‐ POST ‐ TEJRASAINDIA Rajasthan Bikaner 120121030000695Amount for unclaimed and 5.00 26‐AUG‐2012 BHANUBEN GOBARBHAI THESIA NOT AVAILABLE OPP. GANDHIWADI S INDIA Gujarat Rajkot 360410 120267010000172Amount for unclaimed and 4.00 26‐AUG‐2012 AMAR DEEP NOT AVAILABLE HOUSE NO.1230 URBINDIA Haryana Jind 126102 120260000000982Amount for unclaimed and 50.00 26‐AUG‐2012 GRISHMA SECURITIES PVT LTDBSE NOT AVAILABLE 620 , P. J. TOWERS , DINDIA Maharashtra Mumbai City 400023 120291000000020Amount for unclaimed and 1000.00 26‐AUG‐2012 TRIMURTI LAND DEVELOPMENT PNOT AVAILABLE 203,CITY ARCADE, PAINDIA Gujarat Jamnagar 361001 120332000008026Amount for unclaimed and 200.00 26‐AUG‐2012 MUNNA LAL AGARWAL LALA PRAGDAS 43/132 NAWAL KISHOINDIA Uttar Pradesh Lucknow A00032 Amount for unclaimed and 50.00 26‐AUG‐2012 MOHOMAD AMIN G AHMED 31 PARK STREET -

1 | P Age FORM B (Under Rule 8 of ICWA Rules, 2006)

1 | Page FORM B (Under rule 8 of ICWA Rules, 2006) INDIAN COUNCIL OF WORLD AFFAIRS ANNUAL REPORT, 2016-17 1. Introduction During the year, ICWA continued with its mandated activities and accorded high priority to research and study of political, security and economic developments in Asia, North America, Europe, Africa, and Latin America & Caribbean. Global geo-strategic and geo-political developments were analyzed. The conclusions were disseminated in the form of Sapru House Papers, Policy Briefs, Special Reports, Issue Briefs and Viewpoints, which were placed on the ICWA website. A large number of events including lectures, conferences and outreach activities were conducted. The Library was improved and new books were acquired. In line with the advice/recommendation of the last meeting of the Governing Body/Governing Council, ICWA initiated various programmes and activities to propagate and popularize foreign affairs and international relations issues in Hindi by sponsoring activities in various universities outside of Delhi. 2. Constitution of the Council, including changes therein. Shri M. H. Ansari, Vice-President of India, has been the President, ex officio, of the Council since the assumption of the august office of Vice President of India on 11 August, 2007. Ambassador Nalin Surie has been the Director General, ICWA & Member-Secretary of the Council since 24 July, 2015. The Members of the existing Governing Council and Governing Body is attached at Annexure – I&II respectively. 3. Meetings of the Governing Council/Governing Body : 3.1 Meetings of the Governing Council The 14th Meeting of the Council was held on 28th June, 2016 3.2 Meetings of the Governing Body The 15th Meeting of the Governing Body was held on 28th June, 2016 4. -

S. No Name Designation Department 1 DANIEL M. AC Mechanic I AIR CONDITIONING ENG

S. No Name Designation Department 1 DANIEL M. AC Mechanic I AIR CONDITIONING ENG. 2 ANANDAN V AC Mechanic III AIR CONDITIONING ENG. 3 BASKAR M. AC Mechanic III AIR CONDITIONING ENG. 4 EBRAIEM C. AC Mechanic III AIR CONDITIONING ENG. 5 HIMAYAVARMAN G. AC Mechanic III AIR CONDITIONING ENG. 6 KANNAN M AC Mechanic III AIR CONDITIONING ENG. 7 PRABAHKARAN R. AC Mechanic III AIR CONDITIONING ENG. 8 SARAVANAN C AC Mechanic III AIR CONDITIONING ENG. 9 S. ARUN PAUL AC Mechanic IV AIR CONDITIONING ENG. 10 S.ABU BAKKAR SIDDIQ AC Mechanic IV AIR CONDITIONING ENG. 11 JOHN CHRISTY VINOTH D. Accountant - cum - Cashier I BILLING 12 PREMKUMAR G. Accountant - cum - Cashier I ACCOUNTS 13 RAJI P. Accountant - cum - Cashier I ACCOUNTS 14 SARAVANA WILSON I. Accountant - cum - Cashier I ACCOUNTS 15 SHOBA S. Accountant - cum - Cashier I ACCOUNTS 16 SILAMBARASAN R. Accountant - cum - Cashier I ACCOUNTS 17 SUJATHA G.K. Accountant - cum - Cashier I OPHTHALMOLOGY 18 SURESH R. Accountant - cum - Cashier I ACCOUNTS 19 A.ROBERT Accountant - cum - Cashier II PURCHASE 20 DANIEL BALASINGH S Accountant - cum - Cashier II ACCOUNTS 21 DEVA ANBU C Accountant - cum - Cashier II ACCOUNTS 22 DEVI D. Accountant - cum - Cashier II ACCOUNTS 23 E.SENTHIL KUMAR Accountant - cum - Cashier II ACCOUNTS 24 E.VETRIVEL Accountant - cum - Cashier II ACCOUNTS 25 G. VIJAYAKUMAR Accountant - cum - Cashier II ACCOUNTS 26 GOKULAN R Accountant - cum - Cashier II ACCOUNTS 27 GURUBARAN R Accountant - cum - Cashier II ACCOUNTS 28 JABEZ SAMUEL RAJ D Accountant - cum - Cashier II ACCOUNTS 29 K.M. DINESH Accountant - cum - Cashier II ACCOUNTS 30 KESAVAN S. -

Catalogue of the Papers of Captain Lakshmi Sahgal

OF CONTEMPORARY INDIA Catalogue Of The Papers of Captain Lakshmi Sahgal Plot # 2, Rajiv Gandhi Education City, P.O. Rai, Sonepat – 131029, Haryana (India) Captain Lakshmi Sahgal (1914-2012) Freedom fighter, social activist and the first woman commander of Indian National Army, Lakshmi Sahgal nee Swaminadhan was born on 24 October 1914 in Madras (now Chennai) to S. Swaminadhan, a criminal lawyer at Madras High Court, and Ammu Swaminadhan, a social worker and freedom fighter. Inspired by the progressive views of her mother, Lakshmi broke social convention and dogmas from a very early stage speaking out against the caste practices in Kerala. She joined the Queen Mary’s College, Madras in 1932. She was married at a young age to P.K.N Rao, a pilot. However, the marriage was not a success and she returned to her hometown to resume her studies. She completed her MBBS in 1938 from Madras Medical College. She also obtained a diploma in gynaecology and obstetrics from the same college in 1940 and joined the Government Kasturba Gandhi Hospital, Madras. Thereafter, she moved to Singapore and established a clinic for the poor and migrant workers from India. She also got closely associated with the India Independence League, founded in 1941 by Rash Behari Bose. In 1942, during the Japanese occupation of Singapore Dr. Lakshmi provided medical aid to the prisoners of war. Subhas Chandra Bose visited Singapore in July 1943 and took over the leadership of the League along with the Indian National Army. Dr. Lakshmi was inspired and fascinated by the charismatic leadership of Bose and expressed her desire to work with him. -

FORM B (Under Rule 8 of ICWA Rules, 2006) INDIAN COUNCIL of WORLD AFFAIRS ANNUAL REPORT for the Financial Year 2012-13 1

FORM B (Under rule 8 of ICWA Rules, 2006) INDIAN COUNCIL OF WORLD AFFAIRS ANNUAL REPORT For the Financial Year 2012-13 1. Introduction During the year, ICWA continued with its mandated activities under Section 13 of the ICWA Act, 2001. 2. Constitution of the Council, including changes therein. Shri M. H. Ansari, Vice-President of India, was the President, ex officio, of the Council during the year 2012-13. Ambassador Rajiv Kumar Bhatia joined on 27th June, 2012 as Director General, ICWA & Member-Secretary of the Council. A list of the members of the Council is attached. (Annexure – I) A list of the members of the Governing Body is attached. (Annexure – II) 3. Meetings of the Council/Governing Body. 3.1 Meetings of the Council 8th Meeting of the Council: 26th June 2012. 3.2 Meetings of the Governing Body 9th Meeting of the Governing Body: 14th December 2012. 8th Meeting of the Governing Body: 26th June 2012. 4. Meetings of the Committees: A. PROGRAMMES COMMITTEE (i) 18th Meeting held on 14th November, 2012. (ii) 17th Meeting held on 23rd May, 2012. B. FINANCE COMMITTEE (i) 16th Meeting held on 22nd November, 2012 (ii) 15th Meeting held on 23rd May, 2012 Page 1 of 32 C. BUILDING COMMITTEE – No meeting held during the year 2012-2013 D. LIBRARY COMMITTEE – No meeting held during the year 2012-2013 E. RESEARCH COMMITTEE (i) 8th Meeting held on 14th March, 2013 (ii) 7th Meeting held on 5th November, 2012 F. WEBSITE COMMITTEE – No meeting held during the year 2012-2013 The membership of the various Committees mentioned above is at (Annexure – III). -

Reflections on the Conduct of United Nations Peacekeeping Operations Into the Next Two Decades of the 21St Century

MANEKSHAW PAPER No. 60, 2016 Reflections on the Conduct of United Nations Peacekeeping Operations into the Next Two Decades of the 21st Century Lt Gen Satish Nambiar (Retd) D W LAN ARFA OR RE F S E T R U T D N IE E S C CLAWS VI CT N OR ISIO Y THROUGH V KNOWLEDGE WORLD Centre for Land Warfare Studies KW Publishers Pvt Ltd New Delhi New Delhi Editorial Team Editor-in-Chief : Brig Kuldip Sheoran (Retd) Managing Editor : Ms Geetika Kasturi ISSN 23939729 D W LAN ARFA OR RE F S E T R U T D N IE E S C CLAWS VI CT N OR ISIO Y THROUGH V Centre for Land Warfare Studies RPSO Complex, Parade Road, Delhi Cantt, New Delhi 110010 Phone: +91.11.25691308 Fax: +91.11.25692347 email: [email protected] website: www.claws.in CLAWS Army No. 33098 The Centre for Land Warfare Studies (CLAWS), New Delhi, is an autonomous think tank dealing with national security and conceptual aspects of land warfare, including conventional and sub-conventional conflicts and terrorism. CLAWS conducts research that is futuristic in outlook and policy-oriented in approach. © 2016, Centre for Land Warfare Studies (CLAWS), New Delhi Disclaimer: The contents of this paper are based on the analysis of materials accessed from open sources and are the personal views of the author. The contents, therefore, may not be quoted or cited as representing the views or policy of the Government of India, or Integrated Headquarters of MoD (Army), or the Centre for Land Warfare Studies. -

Lt Gen Satish Nambiar Was Commissioned Into the 20Th Battalion of the Maratha Light Infantry on 15 Dec 1957

Lieutenant General Satish Nambiar, PVSM, AVSM, VrC (Retd) (July 1996 to December 2008) Lt Gen Satish Nambiar was commissioned into the 20th Battalion of the Maratha Light Infantry on 15 Dec 1957. He participated in the 1965 and 1971 wars. He commanded two battalions of the Regiment. A graduate of the Australian Staff College, the General Officer served on the General Staff Branch at Divisional Headquarters and as the Additional Director General and later as Director General of Military Operations at Army Headquarters. He raised and commanded the first mechanised brigade group of the Indian Army, and later commanded a mechanised division. He was a member of Indian Army Training Team in Iraq from July 1977 to January 1979. He served was on the faculty of the Defence Services Staff College at Wellington in the Nilgiris. He was also the Military Adviser at the High Commission of India in London from December 1983 to November 1987. As the first Force Commander and Head of Mission of the United Nations forces in the former Yugoslavia (UNPROFOR), he had the distinction of setting up the Mission and commanding it from March 1992 to March 1993. He retired as the Deputy Chief of the Army Staff on 31 August 1994. On 26 January 2009 the General Officer was honoured with Padma Bhushan for his contribution to National Security Affairs. He assumed charge as the Director of United Service Institution (USI) of India on 01 July 1996 and relinquished it on 31 Dec 2008. During the tenure, he was appointed Adviser to Government of Sri Lanka on the peace process in that country from 2002 to 2003. -

The Effects of Pakistan's Nuclear Weapons on Civil-Military Relations in India

The Effects of Pakistan’s Nuclear Weapons on Civil-Military Relations in India Ayesha Ray The development of Pakistan’s nuclear weapons program in the 1980s contained serious implications for Indian civil-military relations in the 1990s. Towards the late 1980s, India’s brief but risky military encounters with Pakistan and the rapid development of its nuclear program dra- matically shaped Indian approaches to the use of nuclear weapons in the 1990s. Not only was there a fundamental shift in Indian political attitudes towards the development of nuclear technology for strategic use, but more importantly, the Indian military began playing a critical role in the development of new strategic doctrines which could effectively deal with a Pakistani nuclear attack. The Indian military’s role in influencing the development of nuclear strategy is a critical part of the evolution in Indian civil-military approaches to nuclear policy. More importantly, the military’s attempts to assert its expertise in nuclear policy are of funda- mental importance in addressing challenges to the division of labor be- tween civilians and the military. Indian Political Thought and Nuclear Strategy in the 1970s To understand how the development of Pakistan’s nuclear weapons program may have affected Indian civil-military relations, it becomes important to revisit Indian approaches to nuclear strategy in the 1970s and 1980s. Interestingly, the Indian case reveals that despite the existence of external security threats in the 1970s, India’s political leadership found no compelling reason to develop nuclear weapons for strategic use. In fact, Dr. Ayesha Ray is an assistant professor of political science at King’s College, Pennsylvania. -

Grant Strategy for India 2020 and Beyond

Krishnappa Venkatshamy Other Titles of Interest This volume presents perspectives on Research Fellow, Institute for Defence issues of importance to India’s grand Studies and Analyses (IDSA). His research strategy. Number of Experts discuss interests include India’s grand strategy, SOUTH ASIA: ENVISIONING A REGIOnaL FUTURE wide ranging security concerns: 2020 and Beyond Grand Strategy Grand Strategy global governance, security politics of Smruti S, Pattanaik socio-economic challenges; regional Israel and comparative strategic cultures. and internal security challenges; His recent publications include- Global ISBN: 978-81-8274-497-4 emerging challenges in foreign policy Power Shifts and Strategic Transition in Asia domain etc. The volume also addresses (ed.), Academic Foundation, 2009, India’s NON-STATE ARMED GROUP IN SOUTH ASIA recent and emerging security Grand Strategic Thought and Practice*(ed.), threats such as left wing extremism, Routledge, (forthcoming November Arpita Anant international terrorism, climate change 2012). He previously led the IDSA National ISBN: 978-81-8274-575-9 for India and energy security, and the role of Strategy Project (INSP). He is currently these for framing a national security leading the Strategic Trends 2050 Project, an 2020 and Beyond strategy for India. The authors in the interdisciplinary study of long-term strategic SPACE SECURITY: NEED FOR GLOBAL CONVERGENCE volume offer insightful answers to futures, sponsored by the Defence Research Arvind Gupta, Amitav Malik, Ajey Lele (Eds.) India for questions such as: What might India and Development Organisation (DRDO). ISBN: 978-81-8274-605-3 do to build a cohesive and peaceful domestic order in the in the next Princy George decades? How could India foster a Research Associate at the Institute for CHina’S PaTH TO POWER: ParTY, MILITARY AND global consensus on the global Defence Studies and Analyses (IDSA) THE POLITICS OF STATE TRANSITION commons that serve India’s interests and works with the Africa, Latin America, Jagannath P.