Erinthesis Total.Pdf (962.6Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Opening the Door of Faith

OPENING THE DOOR OF faith 2012 ANNUAL REPORT DEAR FRIENDS, In the scriptural passage cited by Pope Benedict XVI as he proclaimed the Year of Faith, the apostles received God’s graces and their lives were changed forever. We, too, are changed as we continue to follow Jesus, the true door of faith – the way, the truth and the life. I extend my sincere gratitude to thousands of parishioners who responded to deepening their relationship with Jesus by supporting the initiatives of the Catholic Community Foundation, as seen in the extraordinary success of Rooted in Faith – Forward in Hope. Your tremendous generosity shows that you are committed to the Church being an ongoing, positive influence in people’s lives. WE, TOO, ARE CHANGED AS In this Annual Report of the Catholic Community Foundation, you will read about the direct benefits of your commitment and generosity. Thank you to our pastors, parishioners, WE CONTINUE TO FOLLOW volunteers, donors and Foundation staff and board members for your continued stewardship JESUS, THE TRUE DOOR OF and sharing of God’s grace. FAITH – the WAY, THE Sincerely yours in Christ, TRUTH AND THE LIFE. Bishop of Cleveland DEAR BENEFACTORS, On behalf of the Catholic Community Foundation Board of Directors, I am pleased to share with you our 2012 Annual Report, highlighting the good work being accomplished to ensure the growth of our Catholic faith throughout Northeast Ohio. We have much to celebrate. I am especially pleased to let you know that Rooted in Faith – Forward in Hope has far exceeded our initial goal, with $170 million raised to strengthen parishes, support schools, provide spiritual formation, promote vocations, educate seminarians, care for retired priests and assist the most vulnerable in our community. -

Management Discussion and Analysis FY05 Discussion & Analysis of the Financial Statements

Management Discussion and Analysis FY05 Discussion & Analysis of the Financial Statements Introduction The most recent audited financial statements of the Roman Catholic Archbishop of Boston, a Corporation Sole (Corporation Sole) available are for the two fiscal years ended June 30, 2005. These statements, including the combined financial information for the parishes as a group, the central office, the insurance funds and the endowment funds, are provided in section five of this presentation. The Corporation Sole financial statements are complex. The purpose of this report is to explain what these financial statements are telling us and provide a context to help readers further their understanding of them. This is done by answering a series of key questions about the financial statements, with a focus on the following concepts: What does Corporation Sole own? How is it owned, or who has an interest in it? How did that ownership change during the year? What is the assessment of its financial condition? This analysis also answers questions about such matters as the status of the Revolving Loan Fund, activities of the Parish Reconfiguration Funds, the impact of the Clergy Benefit Funds on Corporation Sole and other matters not readily answered by the audited financial statements. The questions related to the sources and uses of funds for the sexual abuse settlements are the subject of a separate report that is being issued simultaneously with this report and therefore are not included in this discussion. Some underlying principles are important to understand in order to use this analysis effectively. Corporation Sole follows the accounting practices used by not-for-profit organizations. -

CCGR Weekly Newsletter (6-27-21)

The Catholic Community of Gloucester & Rockport HOLY FAMILY PARISH & OUR LADY OF GOOD VOYAGE PARISH _____________________________ Live the Gospel. Share God’s Love. Rebuild the Church. Thirteenth Sunday in Ordinary Time ∙ June 27, 2021 VIVA SAN PIETRO! ONE SOLEMN PROMISE OUR PASTOR’S MMESSAGEESS — PAGE 3 _______________________________________ ___ The Catholic Community of Gloucester & Rockport United in Prayer, Fellowship, and Service Phone: 978-281-4820 Email: [email protected] Website: ccgronline.com Cover Art: Saint Peter Praying by Matthias Stom (1600-1650) CATHOLIC COMMUNITY OF GLOUCESTER & ROCKPORT THIRTEENTH SUNDAY THE CALL TO PRAYER _____________________ A Prayer for Pope Francis SAINT PETER, PRAY FOR US! Lord God, we offer our joyful prayers in thanksgiving for our Holy Father, Pope Francis, who is the Vicar of Christ and Servant of the Servants of God. In Pope Francis, we recognize the successor to Saint Peter, the touchstone for the mission of the Church. We pray that your Holy Spirit will strengthen him as a messenger of love, peace, and unity in our suffering world. We give thanks for the many gifts offered to all of us by this true Shepherd of God’s Church. May he please you in his holiness and guide his flock with love and watchful care, especially the poor, the sick, and the vulnerable. We pledge our love and support for him. With him, we accept the invitation to spread the Good News of the Gospel in word and deed. We offer these prayers through our Lord Jesus Christ, your Son, who lives and reigns with you in the unity of the Holy Spirit, God forever and ever. -

With Law Norw Gone, Maybe @Rder Will Return

an·ni pays a visit to WGBH ~ E13 mCommunity Newspaper Company www.towr mime coln/allstonhnghton FRIDAY, DECEMBER 20, 2002 Vol. 7, No. 21 46 Pages 3 Sections 75¢ With Law norw gone, maybe @rder will return He's in By Phoebe Sweet scandal that has troubled the He's out STAf "There's a lot of anger that can sometimes church throughout the past year reetin 1hc p ~' lor after it became clear that priests the tir t lime a inter not get you off on the right foot with and the laity alike were dissatis G im Apostoli dmin somebody. If you give him a chance he will fied with Law's leadership. istrator of the \rduh ,,c of More than 50 priests, including Boston on Wcdn ·-.da). B1 hop do a good job." Boston College theology pro Richard Lennon outhn xi h1 fessor David Hollenbach, goals for hi s tune lead th Stephen P pe. chainnan of the BC Theology Department signed a letter addressed to Law archdiocese and told re X>n r requesting his resignation. he is "aware that all th cJ 1.: r 1onation last I 1 lay. St. John's Seminar} and an or Some local Catholics might sions [he] will ha\c 1 Ill< k h ' bceo rector of St. John', dained priest for the archdio take comfo11 in someone who will not be accl.11m d." emmar) in Brighton since cese 'Ince I 973. has been called "less charismat b BOSTON HERALD PHOTO BY MARK GARAP<!<EL Lennon, na111 d a ntenm 1999. -

OB NEWS April 09 FINAL.Qxd

Serving Old Brooklyn, Brooklyn Centre & surrounding areas for 30 years www.oldbrooklyn.com April 2009 Volume 31; Number 2 Cleveland City Council new ward boundaries affect Wards 15 & 16 by Robyn Sandys new redistricting plan will divide the two Ballot Issue 39 [email protected] current wards into four different wards — 3, began as a recommenda- 12, 13 and 14. This represents a significant tion from the Charter Many of our readers probably don’t change for these two neighborhoods, a Review Commission to remember the cool autumn day that they change that many will have to adjust to, Cleveland City Council. voted by a significant majority (about 60%) including the CDC which will be affected The Commission rec- for the Charter Amendment, Ballot Issue 39, because of the way that most CDCs are ommended that Council that would reduce the size of Cleveland City funded. Currently, each Council member representation be based Council by either two or four Council seats. receives funds to support programs in their on population and sug- The last reduction of Council was in 1981 ward; more on that later in this article. gested a ratio of one when it shrank from 33 to 21 seats. This The new Ward 3 will be covering the Councilperson for every time the reduction will be from 21 to 19 southeast corner of the old Ward 15, includ- 25,000 citizens. Upon seats. ing the South Hills area. receiving this recom- The change will take place January 1, The new Ward 12 will be covering mendation, Council Photo by George Shuba 2010. -

One Parish, Two Churches

Saint Mary of the Assumption Parish ThThirty-ThirtyirtyThirty---firstfirst Sunday in Ordinary Time ———November—November 3 St. Mary of the Assumpon Brookline, Massachuses Saint Mary of the Assumption Parish The Catholic Community of Brookline, MA 1ne Parish, Two Churches Pastoral 13ces 5 Linden Place Brookline, MA 0.44578311 61878347 0444 FAX 618783473001 www.stmarybrookline.com Saint Mary)s Church Saint Lawrence Church 3 ,inden Place, Brookline Village 774 Boylston St., Rt.9, Chestnut Hill Parish Staff Masses Pastor Fr. Jonathan Gaspar, [email protected] Sunday Masses St. ,awren e Church8 Sunday - 9800 am In esidence Fr. James Ojo 11:30 am Ordinariate Form, 0radional English Catholic Mass Fr. Jim Nunes Fr. Marcin Pudo St. Mary*s Church: Saturday - 4800 pm Sunday - 7830, 10830 am and 12800 noon Deacon: Deacon John Nicholson Weekday Masses [email protected] St. Mary*s Church: Monday - Friday 7830 and 9800 am Music Directors Arthur Rishi-St. Mary’s followed by Daily Rosary & Saturday - 8800 am Warren Hutchison-St. Lawrence Ministries & Activities Business Manager Susan Crapo Pastoral Assistant Mary Slaery St. Mary)s Book Club: ,ast Monday of the month at 7800 pm in St. Mary*s Re tory. eligious Educaon Director Dr. Chris/ne Nadjarian, nadjarian@stmarybrookline. om St. Mary)s Mother)s Prayer Group: Meets on Monday at 10830 am, he k bulle/n for dates. St. Mary of the Assumpon School Dr. 0heresa 1irk, Prin ipal St. Vincent de Paul Society: Contact the re tory. 27 Har3ard Street, 217-522-7184 www.stmarys-brookline.org ,oung Adults Group: Contact the re tory St. -

2010 Annual Meeting

A Blueprint for Responsibility: Responding to Crises with Collaborative Solutions National Leadership Roundtable on Church Management 2010 Annual Meeting June 23–25, 2010 The Wharton School Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Table of Contents Report from the Executive Director .........................................................................................1 Ms. Kerry A. Robinson, Executive Director, National Leadership Roundtable on Church Management Activities and Accomplishments: Achievements of the Leadership Roundtable ............................................................................ 5 Moderator: Ms. Kerry A. Robinson, Executive Director, National Leadership Roundtable on Church Management Panelists: Mr. Thomas Healey, President, Healey Development, LLC Dr. Charles Geschke, Co-Founder and Co-Chairman, Adobe Systems, Inc. Rev. John Wall, President, Catholic Church Extension Society Plenary Discussion Highlights ..................................................................................... 13 Accountability in a World Church: A Global Perspective on the Case for Collaboration ............................................................ 19 Mr. John Allen, Senior Correspondent, National Catholic Reporter and Vatican Correspondent, CNN Plenary Discussion Highlights ..................................................................................... 25 Lessons Learned: The US Response to the Sexual Abuse Crisis .................................................................................. 35 Moderator: Dr. Kathleen -

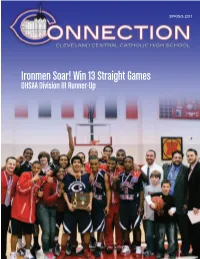

Connection Magazine Spring 2011

ccc_spring11may9b:Layout 1 5/11/11 10:00 AM Page 1 SPRING 2011 Ironmen Soar! Win 13 Straight Games OHSAA Division III Runner-Up ccc_spring11may9b:Layout 1 5/11/11 10:00 AM Page 2 Rooted in Gospel values and Catholic tradition, Cleveland Central Catholic High School educates culturally diverse young men and women of our city and challenges them to deepen their faith The Connection i and responsibly serve God, church and community. T Allen Clark, Fa Michael Vianco Terrell Davis '12, R Vibrant in the City . Preparing All Students to be 21st Century Leaders Pleas ccc_spring11may9b:Layout 1 5/11/11 10:01 AM Page 3 n contents The Connection is published twice a year for Cleveland Central Catholic High School th alumni, parents, faculty, administrators, and friends. CO-EDITORS SPRING 2011 Michele Fusco Scoccola Director of Advancement Ellen Fasko Howard ’66 OLL Faculty and Alumni Editor President’s Letter 4 DESIGN AND LAYOUT Advancement Notes 5 Linda Schellentrager Principal’s Notes 6 CONTRIBUTORS / PHOTOGRAPHY Fundraising Calcutta Event 7 Thanks to Neil C. Lauron of the Columbus Dispatch Honor Roll 8 Allen Clark, Faculty; Ellen Howard, Faculty; William C. Rieter; Elvis Serrano ’96; Michael Viancourt ’86; Class of 1960 OLL; Student contributors: Tiera Collins '12, Terrell Davis '12, Ryan Jackson '12, Angel Poole '12, Te'Angela Quinn '12, Holly Ulery '11. ------------ Cleveland Central Catholic High School Leo P. Hyland President Sister Allison Marie Gusdanovic, SND Principal Dr. Lanny Hollis Central Catholic Family 10 Associate Principal Carmella -

Jackson-Mann and BHS Celebrate Leadership ~PAGE10

Jackson-Mann and BHS celebrate leadership ~PAGE10 - .....• • Community Newspaper Company • www.alistonbrlghtontab.com FRIDAY, APRIL 14, 2006 Vol. 1O~ No. 35 46 Pages • 3 Sections 75¢ BUSINESS LENNON IS LEAVING· CAUSE FOR CAKE Pina parlor parties past hours Local shop slapped with violation By Audltl Guha . Ave. and found about 15 to 20 STAFF WRITER people inside though the lights t 2 a.m., the night is appar outside were switched off, ac ently still young at one cording to a police report. Alocal eatery. There were reportedly four Despite greasing the political peopl behind the counter. wheels and obtaining a 2 a.m. li Whon owner Aman Osmani cense that local police and the saw the officer, he reportedly community were not in favor of, turned off the lights inside and Bravo Pizza got slapped with a li started moving the patrons out. cense premise violation for oper At least one was seen eating a ating after hours on Saturday, ac slice on her way out while anoth cording to reP!'rts. er carried a bortle of Pepsi, re At about 2:20 a.m. on April 8, a ports state. patrolling officer responded to Inside the restaurant, the phone the pizza shop at 160 Brighton PIZZA, page 15 Sf"" PHOTO BY lARA TZANEV Marla Rodriquez, mother of two former Our Lady of jIIe Presentation students, welcomes friend Rich Accerra to her sidewalk party In Fire ravages Oak front of the Brighton Archdiocese Chancery to celebrate Bishop lennon's departure. Celebratink the bishop sdeparture Square home v • By Audltl Guha C(}"organiz.er Steve Ashcroft sported a at passersby as Rodriguez flanded out Draws SO firefighters, 15 engines STAFF WRITER tux, complete with a bow tie, hat and a yel pieces of cake and plastic wine glasses low badge that had a st.~p crossed out in filled with sparkling cider to celebrate By Audltl Guha A giant sheet cake reading "Alleluia Bon STAFF WRITER Voyage" and four bottles of cider were con red. -

Clergy Child Molesters (179) - References / Archive / Blog 7/30/11 3:55 PM

Clergy Child Molesters (179) - References / Archive / Blog 7/30/11 3:55 PM Clergy Child Molesters (179) — References/Archive/Blog • Sacked abuse principal rehired [2010 Roman Catholic (RC) school -NEW*. Hires "enabler."] [2007-08 Bro. Gerard Byrnes* (61) (Christian Brother). RCC. 13 girls (<12).] Warwick Daily News, http://www.warwickdailynews.com.au/ story/2010/12/02/sacked-abuse- principal- rehired-Toowoomba ; December 02, 2010 AUSTRALIA - THE sacked principal at the centre of the child sex abuse scandal at a Toowoomba Catholic primary school has been rehired at a Catholic school in Ipswich. Yesterday families of five girls abused by former teacher Gerard Vincent Byrnes reached a settlement with the Catholic Church's Toowoomba diocese to discontinue their legal proceedings. A further three girls' families are expected to settle their cases next year. Posted by Kathy Shaw at 7:01 PM, Dec 01, 2010 [LOOK BACK: October 2010, April 2010.] (This is the first item of Abuse Chronology: http:// www. multiline. com.au/~johnm/ ethics/ethcont179. htm , and of the Clergy Sex Abuse Tracker, www. bishop- accountability.org/ abusetracker , A Blog by Kathy Shaw, for Wednesday, December 01, 2010) < < Back ^ ^ Child Wise (Australia) Irish Survivors Useful Links Parents For Megan's Law (USA 631 689 2672) Celibacy crept Non-marital REFERENCES 50 171 Overview Outreach Books "Fathers" Secrecy Petition v v Next > > Directories: Main 22 Australia 4 Esperanto Experiments Freedom Georgist Globalism Molestation 171 Religion 4 Submission 9 ^ ^ CONTENTS 1 21 Translate Links Events Books HOME v v INTENTION: A challenge to RELIGIONS to PROTECT CHILDREN Series starts: www.multiline.com.au/~johnm/ethicscontents.htm Visit http://www.bishop-accountability.org/AbuseTracker/ . -

MARY QUEEN of PEACE 4423 Pearl Road Cleveland, OH 44109 Phone 216-749-2323 Fax 216-741-7183

MARY QUEEN OF PEACE 4423 Pearl Road Cleveland, OH 44109 Phone 216-749-2323 Fax 216-741-7183 www.maryqop.org November 3, 2019 Thirty-First Sunday in Ordinary Time Parish Staff Mass Schedule Pastor Fr. Douglas Brown [email protected] VIGIL MASS (SATURDAY): 4:30PM Fr. Richard Bona (In Residence) SUNDAY: 6:45 AM, 8:30 AM & 11:00 AM Fr. Joseph Rodak C.PP.S. (In Residence) WEEKDAYS: MONDAY - SATURDAY 8:00 AM Director of Religious Education Jonathan Kenzig [email protected] Music Director W illiam Schoeffler [email protected] TUESDAYS & THURSDAYS 6:00 PM Jim Goebel [email protected] HOLY DAYS & HOLIDAYS AS ANNOUNCED Business Manager Director of Development Tina Ranta [email protected] Parish Office Hours Parish Secretary Mary Vallo [email protected] Evening & Sat. Parish Secretary Joanne Aspery [email protected] Monday - Friday: 8:30 AM - 5:00 PM Bulletin Editor Dawn Wholaver [email protected] Monday - Thursday Evenings: Director of Maintenance Roger Matthes [email protected] 6:00 PM - 8:00 PM Saturday: 10:00 AM - 4:00 PM CONFESSIONS: Saturdays from 3:00 - 4:00 PM. Weekdays follow- Sunday: 8:30 AM - 12:30 PM ing the 8:00 AM Mass. (Mobile Office in Vestibule of Church) BAPTISM: Please call the parish office to schedule. Pre-Baptism (Office is Closed on Civil Holidays) instructions are required for first-time parents. Parents must be practic- ing Catholics. Children should be baptized soon after birth. School MATRIMONY: Weddings must be scheduled at least 6 months 4419 Pearl Road, Cleveland, OH 44109 prior to the intended date. -

Bishop Lennon to Lead the Catholic Diocese of Cleveland

April 4, 2006 - Bishop Lennon to Lead the Catholic Diocese of Cleveland. Cardinal Seán O’Malley’s statement concerning Bishop Richard Lennon’s appointment as 10th Bishop of the Diocese of Cleveland: “We extend our heartfelt congratulations to Bishop Lennon at the announcement that His Holiness Pope Benedict XVI has named him the 10th Bishop of Cleveland. I wish to express my deep gratitude to Bishop Lennon for his 33 years of faithful service as priest and Bishop to the people of the Archdiocese of Boston. Bishop Lennon´s intellect, commit- ment and deep faith will be a grace and blessing for the Diocese of Cleveland. We assure the Bishop of our continued prayers and best wishes as he begins this new ministry on behalf of the Church.” (Vatican) ... Today, His Holiness Pope Benedict XVI announced the appointment of The Most Reverend Richard Gerard Lennon as Bishop of the Diocese of Cleveland, Ohio on May 5, 2006. Bishop-Designate Lennon will become the 0th Bishop of the 59 year old Diocese, succeeding the Most Rev. Anthony M. Pilla whose retirement was also officially accepted by the Vatican. Bishop-Designate Lennon currently serves in the Archdiocese of Boston as Vicar General and Moderator of the Curia, a key administrative post. Previously, he was appointed as the Apostolic Administrator in Boston where he served from December 2002 until the installation of Bishop (now Cardinal) Sean O ‘ Malley as Archbishop in July 2003 Born 59 years ago in Arlington, Massachusetts, Bishop-Designate Lennon graduated from Catholic High School and then attended Boston College before entering St.