Linguistic Linguistic Landshapes Landshapes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LCSH Section K

K., Rupert (Fictitious character) Motion of K stars in line of sight Ka-đai language USE Rupert (Fictitious character : Laporte) Radial velocity of K stars USE Kadai languages K-4 PRR 1361 (Steam locomotive) — Orbits Ka’do Herdé language USE 1361 K4 (Steam locomotive) UF Galactic orbits of K stars USE Herdé language K-9 (Fictitious character) (Not Subd Geog) K stars—Galactic orbits Ka’do Pévé language UF K-Nine (Fictitious character) BT Orbits USE Pévé language K9 (Fictitious character) — Radial velocity Ka Dwo (Asian people) K 37 (Military aircraft) USE K stars—Motion in line of sight USE Kadu (Asian people) USE Junkers K 37 (Military aircraft) — Spectra Ka-Ga-Nga script (May Subd Geog) K 98 k (Rifle) K Street (Sacramento, Calif.) UF Script, Ka-Ga-Nga USE Mauser K98k rifle This heading is not valid for use as a geographic BT Inscriptions, Malayan K.A.L. Flight 007 Incident, 1983 subdivision. Ka-houk (Wash.) USE Korean Air Lines Incident, 1983 BT Streets—California USE Ozette Lake (Wash.) K.A. Lind Honorary Award K-T boundary Ka Iwi National Scenic Shoreline (Hawaii) USE Moderna museets vänners skulpturpris USE Cretaceous-Paleogene boundary UF Ka Iwi Scenic Shoreline Park (Hawaii) K.A. Linds hederspris K-T Extinction Ka Iwi Shoreline (Hawaii) USE Moderna museets vänners skulpturpris USE Cretaceous-Paleogene Extinction BT National parks and reserves—Hawaii K-ABC (Intelligence test) K-T Mass Extinction Ka Iwi Scenic Shoreline Park (Hawaii) USE Kaufman Assessment Battery for Children USE Cretaceous-Paleogene Extinction USE Ka Iwi National Scenic Shoreline (Hawaii) K-B Bridge (Palau) K-TEA (Achievement test) Ka Iwi Shoreline (Hawaii) USE Koro-Babeldaod Bridge (Palau) USE Kaufman Test of Educational Achievement USE Ka Iwi National Scenic Shoreline (Hawaii) K-BIT (Intelligence test) K-theory Ka-ju-ken-bo USE Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test [QA612.33] USE Kajukenbo K. -

Lunyole Phonology Statement App 1.Doc

Date: 4 th September, 2006 Issue: 1 Status: Approved SIL Uganda-Tanzania Branch Lunyole Project Lunyole Phonology Statement Author: Rev. Enoch Wandera Namulemu Approvers: Steve Nicolle – Linguistics Consultant © SIL International 2006 Document Title: Lunyole Date:4 th September, 2006 Phonology Statement Issue: 1 Status: Approved Table of Contents 1 Distribution List ............................................................................................................................ 5 2 Document Storage: ........................................................................................................................ 6 3 Document History Log .................................................................................................................. 6 4 Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................................... 7 5 INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................... 8 5.1 Name of the Language and its speakers ................................................................................ 8 5.2 Geography ............................................................................................................................. 8 5.3 Demography .......................................................................................................................... 8 5.4 Language family ................................................................................................................... -

Ministry of Education,Science,Technology And

Vote Performance Report and Workplan Financial Year 2015/16 Vote: 013 Ministry of Education, Science, Technology and Sports Structure of Submission QUARTER 3 Performance Report Summary of Vote Performance Cumulative Progress Report for Projects and Programme Quarterly Progress Report for Projects and Programmes QUARTER 4: Workplans for Projects and Programmes Submission Checklist Page 1 Vote Performance Report and Workplan Financial Year 2015/16 Vote: 013 Ministry of Education, Science, Technology and Sports QUARTER 3: Highlights of Vote Performance V1: Summary of Issues in Budget Execution This section provides an overview of Vote expenditure (i) Snapshot of Vote Releases and Expenditures Table V1.1 below summarises cumulative releases and expenditures by the end of the quarter: Table V1.1: Overview of Vote Expenditures (UShs Billion) Approved Cashlimits Released Spent by % Budget % Budget % Releases (i) Excluding Arrears, Taxes Budget by End by End End Mar Released Spent Spent Wage 11.218 9.015 9.015 8.648 80.4% 77.1% 95.9% Recurrent Non Wage 131.229 109.486 108.844 104.885 82.9% 79.9% 96.4% GoU 62.227 41.228 28.424 24.904 45.7% 40.0% 87.6% Development Ext Fin. 200.477 N/A 77.806 77.806 38.8% 38.8% 100.0% GoU Total 204.674 159.728 146.283 138.436 71.5% 67.6% 94.6% Total GoU+Ext Fin. (MTEF) 405.150 N/A 224.089 216.242 55.3% 53.4% 96.5% Arrears 0.642 N/A 0.642 0.553 100.0% 86.1% 86.1% (ii) Arrears and Taxes Taxes** 19.258 N/A 12.804 2.548 66.5% 13.2% 19.9% Total Budget 425.050 159.728 237.535 219.343 55.9% 51.6% 92.3% * Donor expenditure -

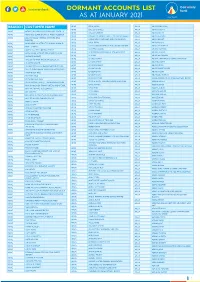

1612517024List of Dormant Accounts.Pdf

DORMANT ACCOUNTS LIST AS AT JANUARY 2021 BRANCH CUSTOMER NAME APAC OKAE JASPER ARUA ABIRIGA ABUNASA APAC OKELLO CHARLES ARUA ABIRIGA AGATA APAC ACHOLI INN BMU CO.OPERATIVE SOCIETY APAC OKELLO ERIAKIM ARUA ABIRIGA JOHN APAC ADONGO EUNICE KAY ITF ACEN REBECCA . APAC OKELLO PATRICK IN TRUST FOR OGORO ISAIAH . ARUA ABIRU BEATRICE APAC ADUKU ROAD VEHICLE OWNERS AND OKIBA NELSON GEORGE AND OMODI JAMES . ABIRU KNIGHT DRIVERS APAC ARUA OKOL DENIS ABIYO BOSCO APAC AKAKI BENSON INTRUST FOR AKAKI RONALD . APAC ARUA OKONO DAUDI INTRUST FOR OKONO LAKANA . ABRAHAM WAFULA APAC AKELLO ANNA APAC ARUA OKWERA LAKANA ABUDALLA MUSA APAC AKETO YOUTH IN DEVELOPMENT APAC ARUA OLELPEK PRIMARY SCHOOL PTA ACCOUNT ABUKO ONGUA APAC AKOL SARAH IN TRUST FOR AYANG PIUS JOB . APAC ARUA OLIK RAY ABUKUAM IBRAHIM APAC AKONGO HARRIET APAC ARUA OLOBO TONNY ABUMA STEPHEN ITO ASIBAZU PATIENCE . APAC AKULLU KEVIN IN TRUST OF OLAL SILAS . APAC ARUA OMARA CHRIST ABUME JOSEPH APAC ALABA ROZOLINE APAC ARUA OMARA RONALD ABURA ISMAIL APAC ALFRED OMARA I.T.F GERALD EBONG OMARA . APAC ARUA OMING LAMEX ABURE CHRISTOPHER APAC ALUPO CHRISTINE IN TRUST FOR ELOYU JOVIN . APAC ARUA ONGOM JIMMY ABURE YASSIN APAC AMONG BEATRICE APAC ARUA ONGOM SILVIA ABUTALIBU AYIMANI APAC ANAM PATRICK APAC ARUA ONONO SIMON ACABE WANDI POULTRY DEVELPMENT GROUP APAC ANYANGO BEATRASE APAC ARUA ONOTE IRWOT VILLAGE SAVINGS AND LOAN ACEMA ASSAFU APAC ANYANZO MICHEAL ITF TIZA BRENDA EVELYN . APAC ARUA OPIO JASPHER ACEMA DAVID APAC APAC BODABODA TRANSPORTERS AND SPECIAL APAC ARUA OPIO MARY ACEMA ZUBEIR APAC APALIKA FARMERS ASSOCIATION APAC ARUA OPIO RIGAN ACHEMA ALAHAI APAC APILI JUDITH APAC ARUA OPIO SAM ACHIDRI RASULU APAC APIO BENA IN TRUST OF ODUR JONAN AKOC . -

Marie-Neige Umurerwa

“For me, switching from one language to another is like switching from one music or rhythm to another, from one tone to another” Hello! My name is Marie-Neige Umurerwa. My family and I live in Lier (a city in the province of Antwerp). I am a Belgian-Rwandan French-speaking. I speak six languages: Kinyarwanda, French, Lingala, Kiswahili, English and Dutch. Thanks to my mother, I have had the opportunity to travel a lot and I lived in different countries. I came to Belgium at the age of 9. That is how I acquired my multilingualism. I have always loved learning languages. For me, switching from one language to another is like switching from one music or rhythm to another, from one tone to another. Depending on what you feel, depending on how you experience things at the moment. For me, language is a translation of emotions. The more languages we speak, the more opportunities we have to access the hearts and emotions of people. Learning one or more languages should be done spontaneously and with pleasure, like a game. The sooner we start learning languages as a child, the more effective it will be. Rwanda has four official languages, and everyone is able to speak more than one language. In a discussion, people easily switch from one language to another. We switch from English to French or from Kinyarwanda to Swahili. After a visit to my home country, I went to a restaurant with my family. The waiter came to take our order. When it was my turn, my eyes were fixed on the menu and without even realizing it I place my order in Kinyarwanda! Of course, my family laughed and when I looked up, I saw the waiter - in shock - asked me; "Excuseer Mevrouw, ik heb niks begrepen, wat zei u?” This situation happens to me often. -

Edinburgh Research Explorer

Edinburgh Research Explorer Translinguistic apposition in a multilingual media blog in Rwanda Citation for published version: Gafaranga, J 2015, 'Translinguistic apposition in a multilingual media blog in Rwanda: Towards an interpretive perspective in language policy research', Language in Society, vol. 44, no. 1, pp. 87-112. https://doi.org/10.1017/S004740451400075X Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1017/S004740451400075X Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: Language in Society Publisher Rights Statement: © Gafaranga, J. (2015). Translinguistic apposition in a multilingual media blog in Rwanda: Towards an interpretive perspective in language policy research. Language in Society, 44(1), 87-112. 10.1017/S004740451400075X General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 24. Sep. 2021 Translinguistic apposition Translinguistic apposition in a multilingual media blog in Rwanda: Towards an interpretive perspective in language policy research Abstract Researchers have called for studies which link the macro and the micro in language policy research. In turn, the notion of ‘micro’ has been theorised as referring either to the micro implementation of macro policies or to micro policies. -

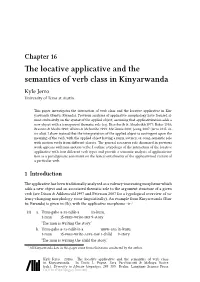

Chapter 16 the Locative Applicative and the Semantics of Verb Class in Kinyarwanda Kyle Jerro University of Texas at Austin

Chapter 16 The locative applicative and the semantics of verb class in Kinyarwanda Kyle Jerro University of Texas at Austin This paper investigates the interaction of verb class and the locative applicative inKin- yarwanda (Bantu; Rwanda). Previous analyses of applicative morphology have focused al- most exclusively on the syntax of the applied object, assuming that applicativization adds a new object with a transparent thematic role (e.g. Kisseberth & Abasheikh 1977; Baker 1988; Bresnan & Moshi 1990; Alsina & Mchombo 1993; McGinnis 2001; Jeong 2007; Jerro 2015, in- ter alia). I show instead that the interpretation of the applied object is contingent upon the meaning of the verb, with the applied object having a path, source, or goal semantic role with motion verbs from different classes. The general locative role discussed in previous work appears with non-motion verbs. I outline a typology of the interaction of the locative applicative with four different verb types and provide a semantic analysis of applicativiza- tion as a paradigmatic constraint on the lexical entailments of the applicativized variant of a particular verb. 1 Introduction The applicative has been traditionally analyzed as a valency-increasing morpheme which adds a new object and an associated thematic role to the argument structure of a given verb (see Dixon & Aikhenvald 1997 and Peterson 2007 for a typological overview of va- lency-changing morphology cross-linguistically). An example from Kinyarwanda (Ban- tu; Rwanda) is given in (1b), with the applicative morpheme -ir:1 (1) a. Umu-gabo a-ra-ndik-a in-kuru. 1-man 1S-pres-write-imp 9-story ‘The man is writing the story.’ b. -

Language Surveys in Developing Nations

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 104 170 FL 006 842 AUTHOR Ohannessian, Sirirpi, Ed.; And Others TITLE Language Surveys in Developing Nations. Papersand Reports on Sociolinguistic Surveys. PUB DATE 75 NOTE 227p. AVAILABLE FROMCenter for Applied Linguistics,1611 North Kent Street, Arlington, Virginia 22209($8.50) EDRS PRICE Mr-$0.76 RC Not Available from EDRS..PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS *Developing Nations; Evaluation Methods; Language Patterns; Language Planning: *LanguageResearch; Language Role; *Language Usage;Nultilingualism; Official Languages; Public Policy;Sociocultural Patterns; *Sociolinguistics; *Surveys ABSTRACT This volume is a selection of papers preparedfor a conference on sociolinguistically orientedlanguage surveys organized by the Center for Applied Linguisticsand held in New York in September 1971. The purpose of theconference vas to review the role and function of such language surveysin the light of surveys conducted in recent years. The selectionis intended to give a general picture of such surveys to thelayman and to reflect the aims of the conference. The papers dealwith scope, problems, uses, organization, and techniques of surveys,and descriptions of particular surveys, and are mostly related tothe Eastern Africa Survey. The authors of theseselections are: Charles A. Ferguson, Ashok R. Kelkar, J. Donald Bowen, Edgar C.Polorm, Sitarpi Ohannessiam, Gilbert Ansre, Probodh B.Pandit, William D. Reyburn, Bonifacio P. Sibayan, Clifford H. Prator,Mervyn C. Alleyne, M. L. Bender, R. L. Cooper aLd Joshua A.Fishman. (Author/AN) Ohannessian, Ferquson, Polonic a a Center for Applied Linqirktie,, mit Language Surveys in Developing Nations papersand reportson sociolinguisticsurveys 2a Edited by Sirarpi Ohannessian, Charles A. Ferguson and Edgar C. Polomd Language Surveysin Developing Nations CY tie papers and reports on 49 LL sociolinguisticsurveys U S OE P MAL NT OF NEAL spt PERMISSION TO REPRODUCETMIT. -

NATIONAL YOUTH SYMPOSIUM YOUTH in AGRIBUSINESS: for Income Generation and Job Creation

NATIONAL YOUTH SYMPOSIUM YOUTH IN AGRIBUSINESS: For income generation and job creation SUMMARY REPORT Debate Winners: Gayaza High School receiving a certificate of recognition during the National Youth Symposium at the Source of the Nile, Jinja National Agricultural & Trade show held on 20th July 2018. “Farmers must deal with the “madness” in farming of practising the same thing over and over and expecting different results. Farmers need to get more organised” said Agume Bless, AgriProFocus youth member. Introduction AgriProFocus in partnership with Uganda National Young Farmers Association (UNYFA) organised a National Youth Symposium held on Friday the 20th July 2018. The symposium was organised under the National Agricultural & Trade Show in Jinja which provides a unique understanding of the entire food chain. The symposium was dubbed under the theme; ‘Youth in agribusiness for income generation and job creation’ with an overall objective of unlocking the underlying business opportunities for youth in the agribusiness sector. In order to achieve the above mentioned objective, the day’s program consisted of the following activities; 1. Keynote Address on Youth in Agribusiness: opportunities for income enhancement and job creation. 2. A panel of discussants on topical issues i.e learning opportunities, agribusiness opportunities 3. A School’s Agribusiness debate between Gayaza High school and Namilyango College 4. Sharing of Success Stories by the youth entrepreneurs. Participants: The symposium was attended by a cross section of people from civil society organisations, students from different schools at different levels, farmer organisations, Government representatives, the media, the private sector as well as development partners. During the symposium, a total of 100 participants who expressed interest to join the AgriProFocus online platform were registered. -

Culture, Minorities and Linguistic Rights in Uganda

CULTURE, MINORITIES AND LINGUISTIC RIGHTS IN UGANDA: THE C ASE O F T HE B ATWA A ND T HE Ik Kabann I.B. Kabananukye and Dorothy Kwagala Copyright Human Rights & Peace Centre, 2007 ISBN 9970-511-10-x HURIPEC Working Paper No. 11 June, 2007 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS...........................................................ii LIST OF TABLES AND FIGURES.................................................................iii SUMMARY OF THE REPORT AND POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS...............iv I. INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND.......................................1 II. CONTEXTUALIZING THE CASE OF ETHNIC MINORITIES.............3 2.1 ENHANCING THE UNDERSTANDING OF ETHNIC MINORITIES.........................3 2.2 CONTEXTUALIZING MINORITIES’ CULTURE AND LANGUAGE........................4 2.3 THE LANGUAGE FACTOR: CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES.....................5 2.3.1 Understanding the Importance of Language.......................5 2.3.2 Ethnic Minorities’ Languages.............................................8 III. MINORITIES AND UGANDA’S LINGUSITIC & ETHNIC GROUPS...9 3.1 THE CASE OF THE BATWA.................................................................11 3.1.1 Batwa distribution by Region and District.........................12 3.1.2 Comparision of the Batwa and the Bakiga.......................14 3.2 THE CASE OF THE IK...................................................................16 3.2.1 Distribution of Ik Peoples by Region in Uganda................17 3.2.2 Distribution of Ik by Districts in Uganda..........................17 -

Classified Adverts

Croc’s 02.qxd 4/29/2011 6:54 PM Page 1 46 NEW VISION, Monday, May 2, 2011 CLASSIFIED ADVERTS RABBAI KONSULT (U) LTD P.O BOX 71, KAMPALA Real Estates Ltd RONAR CHAMBERS “With Trust & Honesty” Estate Developers NAMIREMBE/BAKULI RD. HOSSANA REAL RABBAI REAL ESTATES “.... your place to call home” (Next to TOTAL Petrol Station) .....we settle you HERITAGE SITES LTD CALL: 0712 252 605, Well surveyed plots with ready ESTATES LTD 0772 850 763, 0312 513444 Mailo Land Titles. 1. MUKONO-KYETUME RD. JUBILEE REAL CANAAN SITES with lake view overlooking PLOT 20 OLD K’LA NEAR ST MATIA PLANNED PLOTS WITH 1. GAYAZA-ZIROBWE ESTATES LTD DEALS OF THE WEEK WELL PLANNED AND ORGANISED 1 Km from tarmac Mukono University FORMERLY MULUMBA CHURCH PRIVATE MAILO LAND ESTATES WITH MAILO LAND PLOTS FOR SALE TITLES 50 x 100ft - 3.6m 50 x 100ft = 5m GLORYLAND REAL ESTATES LTD. “FIRST STEP TO NEW HOME” TITLES, WATER & POWER. 100 x 100ft - 7.2m 100 x 100ft = 10m Najjera-Buwate 25 dec - 45m GET A HOME IN OUR WELL 1. VICTORIA GARDENS 2. BULOBA-MITYANA RD. 2. GAYAZA - NAKASAJJA - Well planned plots with Entebbe Road, Kitende 50 1. GAYAZA NEAR 2 km from main road PLANNED ESTATES: on the shores of Lake Victoria on a hill and green Mailo land titles, water dec 45m Manyangwa, Kabubbu 1.5km from tarmac 50 x 100ft - 4.5m Matugga-Kungu several SEVERAL PLOTS WITH MAILO environment LAND TITLES AT HAND. Trading Centre with hill 60 x 100ft - 23m 100 x 100ft - 9m and power. -

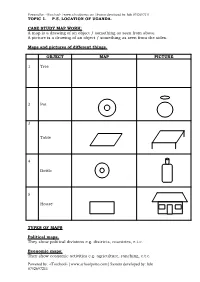

Lule 0752697211 TOPIC 1. P.5. LOCATION of UGANDA

Powered by: -iToschool- | www.schoolporto.com | System developed by: lule 0752697211 TOPIC 1. P.5. LOCATION OF UGANDA. CASE STUDY MAP WORK: A map is a drawing of an object / something as seen from above. A picture is a drawing of an object / something as seen from the sides. Maps and pictures of different things. OBJECT MAP PICTURE 1 Tree 2 Pot 3 Table 4 Bottle 5 House TYPES OF MAPS Political maps. They show political divisions e.g. districts, countries, e.t.c. Economic maps: They show economic activities e.g. agriculture, ranching, e.t.c. Powered by: -iToschool- | www.schoolporto.com | System developed by: lule 0752697211 Powered by: -iToschool- | www.schoolporto.com | System developed by: lule 0752697211 Physical maps; They show landforms e.g. mountains, rift valley, e.t.c. Climate maps: They give information on elements of climate e.g. rainfall, sunshine, e.t.c Population maps: They show population distribution. Importance of maps: i. They store information. ii. They help travellers to calculate distance between places. iii. They help people find way in strange places. iv. They show types of relief. v. They help to represent features Elements / qualities of a map: i. A title/ Heading. ii. A key. iii. Compass. iv. A scale. Importance elements of a map: Title/ heading: It tells us what a map is about. Key: It helps to interpret symbols used on a map or it shows the meanings of symbols used on a map. Main map symbols and their meanings S SYMBOL MEANING N 1 Canal 2 River 3 Dam 4 Waterfall Powered by: -iToschool- | www.schoolporto.com | System developed by: lule 0752697211 Powered by: -iToschool- | www.schoolporto.com | System developed by: lule 0752697211 Railway line 5 6 Bridge 7 Hill 8 Mountain peak 9 Swamp 10 Permanent lake 11 Seasonal lake A seasonal river 12 13 A quarry Importance of symbols.