Mythologising Monteverdi: the Marriage of Venus and Mercury Angela Voss All Teems with Symbol: the Wise Man Is He Who in Any One Thing Can Read Another.1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Monteverdi Claudio

MONTEVERDI CLAUDIO Compositore italiano (Cremona 15 V 1567 - Venezia 29 XI 1643) 1 Era il figlio maggiore di Baldassarre, uno speziale che abitava nei pressi del duomo, e di Maddalena, morta quando Claudio aveva otto anni. Studiò musica con il maestro di cappella del duomo di Cremona, M. A. Ingegneri e già all'età di quindici anni pubblicò una raccolta di Sacrae cantiunculae alla quale seguirono l'anno seguente alcuni Madrigali spirituali e nel 1535 un volume di Canzonette. Il 1º Libro de Madrigali a 5 voci apparve nel 1587, seguito dal 2º Libro tre anni dopo. La prima vera attività di cui si ha notizia fu quella di suonatore di viola alla corte del duca Vincenzo 1° di Mantova, tra il 1590 ed il 1592. In quest'ultimo anno pubblicò il 3º Libro de Madrigali. Nel 1595 accompagnò il duca di Mantova in Ungheria per la guerra contro i Turchi, e nel 1599 seguì nuovamente il duca nelle Fiandre dove ebbe proficui contatti con la musica francese. In questo stesso anno sposò la cantante Claudia Cattaneo da cui ebbe tre figli. Nel 1601 fu nominato maestro di cappella alla corte dei Gonzaga a Mantova. Nel 1603 riprese a pubblicare le sue opere con il 4º Libro de Madrigali, al quale due anni dopo seguì il 5º Libro: queste opere suscitarono furiose polemiche e vennero violentemente attaccate per la loro modernità da un monaco bolognese, G. M. Artusi. La risposta a queste critiche apparve nella prefazione (Dichiarazione) dell'opera seguente, Scherzi musicali (1607) dove il fratello di Monteverdi, Giulio Cesare, che ne curò l'edizione, espresse le ragioni che avevano spinto il compositore ad adottare un sistema armonico così avanzato. -

MONTEVERDI's OPERA HEROES the Vocal Writing for Orpheus And

MONTEVERDI’S OPERA HEROES The Vocal Writing for Orpheus and Ulysses Gustavo Steiner Neves, M.M. Lecture Recital Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS Karl Dent Chair of Committee Quinn Patrick Ankrum, D.M.A. John S. Hollins, D.M.A. Mark Sheridan, Ph.D. Dean of the Graduate School May, 2017 © 2017 Gustavo Steiner Neves Texas Tech University, Gustavo Steiner Neves, May 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT iii LIST OF MUSICAL EXAMPLES iv LIST OF TABLES iv CHAPTER I: INTRODUCTION 1 Thesis Statement 3 Methodology 3 CHAPTER II: THE SECOND PRACTICE AND MONTEVERDI’S OPERAS 5 Mantua and La Favola d’Orfeo 7 Venice and Il Ritorno d’Ulisse in Patria 13 Connections Between Monteverdi’s Genres 17 CHAPTER III: THE VOICES OF ORPHEUS AND ULYSSES 21 The Singers of the Early Seventeenth Century 21 Pitch Considerations 27 Monteverdi in the Twentieth and Twenty-First Centuries 30 Historical Recordings and Performances 32 Voice Casting Considerations 35 CHAPTER IV: THE VOCAL WRITING FOR ORPHEUS AND ULYSSES 37 The Mistress of the Harmony 39 Tempo 45 Recitatives 47 Arias 50 Ornaments and Agility 51 Range and Tessitura 56 CHAPTER V: CONCLUSIONS 60 BIBLIOGRAPHY 63 ii Texas Tech University, Gustavo Steiner Neves, May 2017 ABSTRACT The operas of Monteverdi and his contemporaries helped shape music history. Of his three surviving operas, two of them have heroes assigned to the tenor voice in the title roles: L’Orfeo and Il Ritorno d’Ulisse in Patria. -

Musical Fire: Literal and Figurative Moments of "Fire" As Expressed in Western Art Music from 1700 to 1750 Sean M

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2003 Musical Fire: Literal and Figurative Moments of "Fire" as Expressed in Western Art Music from 1700 to 1750 Sean M. Parr Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF MUSIC MUSICAL FIRE: LITERAL AND FIGURATIVE MOMENTS OF “FIRE” AS EXPRESSED IN WESTERN ART MUSIC FROM 1700 TO 1750 by Sean M. Parr A Thesis submitted to the School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2003 The members of the Committee approve the thesis of Sean M. Parr defended on August 20, 2003. ________________________ Charles E. Brewer Professor Directing Thesis ________________________ Jeffery Kite-Powell Committee Member ________________________ Roy Delp Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Musical Examples...................................................................................................iv Abstract................................................................................................................................v 1. MUSIC, AFFECT, AND FIRE.......................................................................................1 2. KINDLING FIRE: MONTEVERDI AND THE STILE CONCITATO........................19 3. THE FLAMES OF FRANCE AND GERMANY........................................................36 -

I Fagiolini Barokksolistene Robert Hollingworth Director

I Fagiolini Barokksolistene Robert Hollingworth director CHAN 0760 CHANDOS early music © Graham Slater / Lebrecht Music & Arts Photo Library Bust of Claudio Monteverdi by P. Foglia, Cremona, Italy 3 4 Zefiro torna, e ’l bel tempo rimena 3:29 (1567 – 1643) Claudio Monteverdi from Il sesto libro de madrigali (1614) Anna Crookes, Clare Wilkinson, Robert Hollingworth, Nicholas Mulroy, 1 Questi vaghi concenti 7:06 Charles Gibbs from Il quinto libro de madrigali (1605) Choir I: Julia Doyle, Clare Wilkinson, Richard Wyn Roberts, 5 Zefiro torna, e di soavi accenti 6:13 Nicholas Mulroy, Charles Gibbs from Scherzi musicali cioè arie, & madrigali in stil Choir II: Anna Crookes, William Purefoy, Nicholas Hurndall Smith, recitativo… (1632) Eamonn Dougan Nicholas Mulroy, Nicholas Hurndall Smith Strings: Barokksolistene Continuo: Eligio Quinteiro (chitarrone), Joy Smith, Continuo: Eligio Quinteiro (chitarrone), Joy Smith, Steven Devine Catherine Pierron (harpsichord) 2 T’amo, mia vita! 2:53 6 Ohimè, dov’è il mio ben? 4:44 from Il quinto libro de madrigali (1605) from Concerto. Settimo libro de madrigali (1619) Julia Doyle, Clare Wilkinson, Nicholas Mulroy, Eamonn Dougan, Charles Gibbs Julia Doyle, Clare Wilkinson Continuo: Joy Smith, Eligio Quinteiro (chitarrone) Continuo: Joy Smith, Eligio Quinteiro (chitarrone) 7 3 Ohimè il bel viso 4:51 Si dolce è ’l tormento 4:27 from Carlo Milanuzzi: from Il sesto libro de madrigali (1614) Quarto scherzo delle ariose (1624) Julia Doyle, Clare Wilkinson, Nicholas Mulroy, Eamonn Dougan, vaghezze… Charles Gibbs Nicholas -

Monteverdi's Orfeo As Artistic Creed

Ars Polemica: Monteverdi’s Orfeo as artistic creed Uri Golomb Published in Goldberg: Early Music Magazine 45 (April 2007): 44-57. The story of Orpheus is the ultimate test for any musician’s skill. By choosing to set this myth to music, composers declare themselves capable of creating music that would credibly seem to melt the hearts of beasts, humans and gods. They also reveal which style of musical writing is best suited, in their view, for expressing the most intense emotions. Three of the earliest operas are based on this myth. There is, however, a crucial difference between Ottavio Rinuccini’s Euridice, which served as libretto for two operas (by Jacopo Peri in 1600, and by Giulio Caccini in 1602), and Alessandro Striggio’s Orfeo, the libretto for Claudio Monteverdi’s first opera (1607). In the Prologue that opens Rinuccini’s opera, the Muse of Tragedy sings the virtues of pastoral dramas with happy endings. In Striggio’s Prologue, La Musica proclaims her powers to move human souls. In both cases, the prologues set the tone for the remainder of the drama: music and its power are much more central in Striggio’s libretto than they are in Rinuccini’s. Striggio’s emphasis fitted well with Monteverdi’s own philosophy. At the time of Orfeo, the composer was participating in a heated debate on the nature and power of music. He did so concisely and reluctantly, promising a theoretical treatise and then failing to deliver. His theoretical statements, then and later, are complemented by his settings of several texts that focus on music, its style and its powers, Orfeo being the most ambitious. -

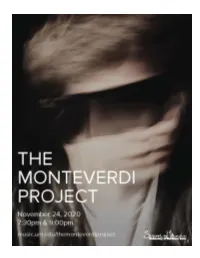

The Monteverdi Project"

From the Director Good Evening All, I am overjoyed to be writing my first director's note for UNI Opera! Welcome to "The Monteverdi Project". Tonight we feature several students from the School of Music in three short pieces by Claudio Monteverdi. It was a joy to work with these artists and help them interpret these works through a modern lens. It is thrilling to produce an evening of music that is as striking today as it was when it was written almost four HUNDRED years ago (Il combattimento di Tancredi e Clorinda premiered in 1624!). Please join me in recognizing the bravery and discipline these students have that allowed this evening to come to fruition. Despite a worldwide pandemic, these artists opened their hearts and allowed us to all be together again, even if only just for a little while. With deepest gratitude, Richard Gammon Director of Opera Program 7:30 p.m. performance “Lamento della ninfa” La ninfa Athena-Sadé Whiteside Coro Aricson Jakob, Dylan Klann, Brandon Whitish Actor Collin Ridgley “Lamento d’Arianna” -fragment- Arianna Joley Seitz “Il combattimento di Tancredi e Clorinda” Il testo Alyssa Holley Tancredi Jovon Eborn Clorinda Deanna Ray Eberhart -INTERMISSION- 9 p.m. performance “Lamento della ninfa” La ninfa Athena-Sadé Whiteside Coro Aricson Jakob, Dylan Klann, Brandon Whitish Actor Collin Ridgley “Lamento d’Arianna” -fragment- Arianna Joley Seitz “Il combattimento di Tancredi e Clorinda” Il testo Alyssa Holley Tancredi Aricson Jakob Clorinda Madeleine Marsh Production Team Conductor/Harpsichordist . .Korey Barrett Stage Director . Richard Gammon Set and Lighting Designer . .W. Chris Tuzicka Costume Designer . -

A Study of Monteverdi's Three Genera from the Preface to Book Viii of Madrigals in Relation to Operatic Characters in Il

A STUDY OF MONTEVERDI’S THREE GENERA FROM THE PREFACE TO BOOK VIII OF MADRIGALS IN RELATION TO OPERATIC CHARACTERS IN IL RITORNO D’ULISSE IN PATRIA AND L’INCORONAZIONE DI POPPEA _______________________________________ A Thesis presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri-Columbia _______________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts _____________________________________________________ by JÚLIA COELHO Dr. Judith Mabary, Thesis Advisor JULY 2018 © Copyright by Júlia Coelho 2018 All Rights Reserved The undersigned, appointed by the Dean of the Graduate School, have examined the thesis entitled A STUDY OF MONTEVERDI’S THREE GENERA FROM THE PREFACE TO BOOK VIII IN RELATION TO OPERATIC CHARACTERS IN IL RITORNO D’ULISSE IN PATRIA AND L’INCORONAZIONE DI POPPEA presented by Júlia Coelho, a candidate for the degree of Master of Arts, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. ________________________________________ Professor Judith Mabary ________________________________________ Professor Michael J. Budds ________________________________________ Professor William Bondeson ________________________________________ Professor Jeffrey Kurtzman ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Over the last years, I have been immensely fortunate to meet people who have helped me tremendously—and still do—in building my identity as an aspiring scholar / performer in the Early Music field. The journey of researching on Claudio Monteverdi that culminated in this final thesis was a long process that involved the extreme scrutiny, patience, attentive feedback, and endless hours of revisions from some of these people. To them, I am infinitely grateful for the time they dedicated to this project. I want to ex- press first my deep gratitude to my professors and mentors, Dr. -

The Selected Sacred Solo Vocal Motets of Claudio Monteverdi Including Confitebor Tibi, Domine

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Major Papers Graduate School 2007 The selected sacred solo vocal motets of Claudio Monteverdi including Confitebor tibi, Domine Kimberly Ann Roberts Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_majorpapers Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Roberts, Kimberly Ann, "The es lected sacred solo vocal motets of Claudio Monteverdi including Confitebor tibi, Domine" (2007). LSU Major Papers. 24. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_majorpapers/24 This Major Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Major Papers by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE SELECTED SACRED SOLO VOCAL MOTETS OF CLAUDIO MONTEVERDI INCLUDING CONFITEBOR TIBI, DOMINE A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts In The School of Music By Kimberly Roberts B.M., Simpson College, 1998 M.M., Louisiana State University, 2000 December 2007 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT…………………………………………………………………………..….iii CHAPTER 1 BIOGRAPHICAL AND STYLISTIC INFORMATION…………………1 2 MONTEVERDI’S SACRED SOLO VOCAL MOTETS.........................13 Confitebor tibi, Domine from the Selva morale e spirituale ....…15 -

Claudio MONTEVERDI Et Son TEMPS

Claudio MONTEVERDI et son TEMPS FESTIVAL du COMMINGES ----- Auteur : Gérard BEGNI – Edition 1, 30 décembre 2015 1 Toccata ouvrant l’ « Orfeo » 2 SOMMAIRE • 1 - LES ANNEES D’APPRENTISSAGE ............................................................................................................ 7 1.1 – Jeunesse et formation .......................................................................................................................... 7 1.2 – Un jeune maître. ................................................................................................................................... 7 1.3 – Les trois premières œuvres. ................................................................................................................. 8 1.4 – Les deux premiers cahiers de madrigaux ............................................................................................. 9 1.4.1 – Les circonstances et les études de Monteverdi. ............................................................................ 9 1.4.2 – Le premier livre de madrigaux (1587)............................................................................................ 9 1.4.3 – Le second livre de madrigaux (1590) ........................................................................................... 10 • 2 – Les DEBUTS à MANTOUE – CAMPAGNES et VOYAGES ...................................................................... 10 2.1 – Mantoue – Le troisième livre de madrigaux ...................................................................................... -

Anima Eterna Brugge Olv

muziek Anima Eterna Brugge olv. Jos van Immerseel za 21 okt 2017 / Grote podia / Blauwe zaal 20 uur / pauze ± 20.50 uur / einde ± 22 uur inleiding 19.15 uur / Magda De Meester in gesprek met luitist Wim Maeseele / Blauwe foyer 2017-2018 Monteverdi Jongerenopera Muziektheater Transparant za 26 & zo 27 aug 2017 Ensemble Oltremontano, Collegium Cartusianum & Kölner Kammerchor olv. Peter Neumann za 7 okt 2017 Anima Eterna Brugge olv. Jos van Immerseel klavecimbel & orgel za 21 okt 2017 Collegium Vocale Gent olv. Philippe Herreweghe zo 22 okt 2017 Ricercar Consort olv. Philippe Pierlot wo 28 feb 2018 tekst programmaboekje Tino Haenen coördinatie programmaboekje deSingel Anima Eterna Brugge vertalingen gezongen teksten Jo Libbrecht boventiteling Capiche surtitling D/2017/5.497/86 Jos van Immerseel muzikale leiding, klavecimbel & orgel Christoph & Julian Prégardien tenor Marianne Beate Kielland mezzosopraan Claudio Monteverdi (1567-1643) Il Combattimento di Tancredi e Clorinda 21’ (uit Achtste Madrigalenboek) Tempro la Cetra 9’ (uit Zevende Madrigalenboek) Lamento d’Arianna 17’ pauze Selectie uit ‘Il Ritorno d’Ulisse in Patria’: 22’ Dormo ancora o son desto? Cara e lieta gioventÙ Lieto cammino O padre sospirato - O figlio desiato Interrotte Speranze 4’ (uit Zevende Madrigalenboek) Selectie uit ‘L’Orfeo’: Possente spirto 11’ Perché a lo sdegno - Saliam cantando al cielo 7’ Gelieve uw GSM uit te schakelen De inleidingen kan u achteraf beluisteren via Reageer en win www.desingel.be Op www.desingel.be kan u uw visie, opinie, commentaar, Selecteer hiervoor voorstelling / concert / appreciatie, … betreffende het programma van deSingel tentoonstelling van uw keuze. met andere toeschouwers delen. Selecteer hiervoor voorstelling / concert / tentoonstelling van uw keuze. -

Cd I Secular Vocal Music and the Birth of Opera 1. Non Sa Che Sia

CD I SECULAR VOCAL MUSIC AND THE BIRTH OF OPERA 1. Non sa che sia dolore Luzzascho Luzzaschi 2’34 2. O dolcezze amarissime Ludovico Agostini 3’33 DOULCE MEMOIRE (dir. Denis Raisin Dadre) Véronique Bourin, Axelle Bernage, Christel Boiron: sopranos Pascale Boquet: lute / Lucas Guimaraes Peres: lirone Angélique Mauillon: harp/ Elisabeth Geiger: harpsichord 3. Udite, selve, mie dolce parole Anonymous 6’31 LE MIROIR DE MUSIQUE Giovanni Cantarini: tenor / Baptiste Romain: lira da braccio La Pellegrina 4. Dalle più alte sfere Emilio de Cavalieri 4’46 5. O fortunato giorno a 7 cori Christofano Malvezzi 2’29 6. Dunque fra torbide onde Jacopo Peri 5’00 7. O che nuovo miracolo Emilio de Cavalieri 5’18 TAVERNER CONSORT, CHOIR & PLAYERS ( dir. Andrew Parrott) Emma Kirkby: soprano (4) / Nigel Rogers, Andrew King, Rogers Covey-Crump: tenors (6) L’Euridice Giulio Caccini 8. Atto I, scena 2: Per quel vago boschetto (Dafne, Arcetro) 3’39 9. Attto I, scena 2: Cruda morte (Ninfa del coro / Coro) 6’11 10. Atto II, scena 4: Funeste piaggie (Orfeo) 3’43 11. Atto III, scena 5: Gioite al canto mio 8’00 (Orfeo, Euridice, Arcetro, Aminta, Dafne, Coro) SCHERZI MUSICALI (dir. Nicolas Achten) Nicolas Achten: baritone & theorbo (Orfeo) Céline Vieslet: soprano (Euridice) / Magid El-Bushra: countertenor (Dafne) / Marie de Roy: soprano (Ninfa) / Reinoud van Mechelen: tenor (Arcetro) / Sarah Ridy: harp / Eriko Semba: lirone / Simon Linné: theorbo guitar / Francesco Corti: harpsichord, organ 210 L’Orfeo Claudio Monteverdi 12. Toccata 1’09 Gilles Rapin, Joël Lahens, Serge Tizac, François Février, Hervé Defrance: mute natural trumpets 13.