Do “Brain-Training” Programs Work? 2016, Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cognitive Training for Older Adults: What Is It and Does It Work? Alexandra Kueider, Krystal Bichay, and George Rebok

Issue Brief OCTOBER 2014 Cognitive Training for Older Adults: What Is It and Does It Work? Alexandra Kueider, Krystal Bichay, and George Rebok Older adults are more likely to fear losing their mental abilities than their physical abilities.1 But a growing body of research suggests that, for most people, mental decline isn’t inevitable and may even be reversible. It is now becoming clear that cognitive health and dementia prevention must be lifelong pursuits, and the new approaches springing from a better understanding of the risk factors for cognitive impairment are far more promising than current drug therapies. Key points from our analysis of the current evidence What Is Known About Cognitive Training Now? include the following: Aggressive marketing notwithstanding, drugs mar- ■■ Cognitive training can improve cognitive abilities. keted for dementias such as AD do little to maintain Dementia drugs cannot. cognitive and functional abilities or slow the prog- ress of the disease. In contrast to drugs are mental ■■ No single cognitive training program stands out exercises to improve cognitive abilities. Dr. Richard as superior to others, but a group format based Suzman, Director of the Division of Behavioral and on multiple cognitive strategies seems the most Social Research at the National Institute on Aging promising. (NIA), states, “These sorts of interventions are poten- tially enormously important. The effects [of cogni- ■■ Research comparing cognitive exercise tive training interventions] were substantial. There approaches is still thin. Rigorous evaluation stan- isn’t a drug that will do that yet, and if there were, it dards are needed. would probably have to be administered with mental exercises.”2 ■■ Cognitive training could reduce health care costs by helping older individuals maintain a healthy Controversy and confusion still surround the efficacy and active lifestyle. -

CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS Nintendo Co., Ltd

Earnings Release CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS Nintendo Co., Ltd. and Consolidated Subsidiaries May 25, 2006 Nintendo Co., Ltd. 11-1 Kamitoba hokotate-cho, Minami-ku, Kyoto 601-8501 Japan FINANCIAL HIGHLIGHTS 1. Consolidated results for the years ended March 31, 2005 and 2006 (1) Consolidated operating results (Amounts below one million are rounded down) Income before Income Taxes Net Sales Operating Income Net Income and Extraordinary Items million yen % million yen % million yen % million yen % Year ended March 31, 2006 509,249 (1.2) 90,349 (19.0) 160,759 10.6 98,378 12.5 Year ended March 31, 2005 515,292 0.1 111,522 3.6 145,292 189.8 87,416 163.3 Income before Income Tax Income before Income Tax Net Income per Share Return on Equity (ROE) and Extraordonary Items on and Extraordinary Items to Total Assets Sales yen % % % Year ended March 31, 2006 762.28 10.4 14.0 31.6 Year ended March 31, 2005 662.96 9.7 13.6 28.2 [Notes] *Average number of shares outstanding: Year ended March 31, 2006: 128,821,844 shares, Year ended March 31, 2005: 131,600,201 shares *Percentage for net sales, operating income, income before income taxes and extraordinary items, and net income show increase (decrease) from the previous annual accounting period. (2) Consolidated financial position Ratio of Net Worth Shareholders' Total Assets Shareholders' Equity to Total Assets Equity per Share million yen million yen % yen Year ended March 31, 2006 1,160,703 974,091 83.9 7,613.79 Year ended March 31, 2005 1,132,492 921,466 81.4 7,082.68 [Notes] *Number of shares -

Press Release Third Annual National Speakers

PRESS RELEASE CONTACT: Veronica S. Laurel CHRISTUS Santa Rosa Foundation 210.704.3645 office; 210.722-5325 mobile THIRD ANNUAL NATIONAL SPEAKERS LUNCHEON HONORED TOM FROST AND FEATURED CAPTAIN“SULLY” SULLENBERGER Proceeds from the Luncheon benefit the Friends of CHRISTUS Santa Rosa Foundation SAN ANTONIO – (April, 3, 2013) Today, the Friends of CHRISTUS Santa Rosa Foundation held its Third Annual National Speakers Luncheon to honor Tom C. Frost, Jr. with the Beacon Award for his passionate service to the community, and featured Captain Chesley B. “Sully” Sullenberger, III as the keynote speaker. Proceeds from the event will benefit programs supported by the Foundation. The Friends of CHRISTUS Santa Rosa Foundation supports the health and wellness of adults throughout south and central Texas by raising money for innovative programs and equipment for four general hospitals and regional health and wellness outreach programs in the San Antonio Medical Center, Westover Hills, Alamo Heights and New Braunfels. The National Speakers Luncheon celebrates the contributions of Frost by honoring him with the Friends of CHRISTUS Santa Rosa Beacon Award. Frost is chairman emeritus of Frost Bank and is the fourth generation of his family to oversee the bank founded by his great grandfather, Colonel T.C. Frost in 1868. He has a long history of community service, having served on the Board of Trustees for the San Antonio Medical Foundation, the Texas Research and Technology Foundation and Southwest Research Institute. He has served on executive committees, boards and initiatives for the San Antonio Livestock Exposition, the McNay Art Museum, the Free Trade Alliance and the YMCA, to name just a few. -

Understanding Cognitive Skills and Brain Training Jennifer L

Understanding Cognitive Skills and Brain Training Jennifer L. Fisher, Ph.D., ABPP Reading Center, Rochester, MN November 14, 2012 Who am I (not)? ! Ph.D. in Child Psychology from Arizona State University; Board Certified through ABPP 2006 ! Fellowship at Mayo Clinic 1996-1998; Consultant 1998-2007; Supplemental Consultant 2008-present ! Specialty in Pediatric Psychology, treating children with physical illnesses (no neuropsychology specialty). ! Most important credential: Mother of two children, Mimi and Myles, one of whom has special learning issues Overview of Presentation ! Intelligence versus Achievement ! Cognitive skills – building blocks of achievement ! What is a learning disability? ! Using cognitive training to address LD: From Orton- Gillingham to online brain training ! Overview of current brain training efforts ! Buyer beware! Intelligence vs. Achievement ! Intelligence – ! Your capacity to learn, solve problems, think abstractly, adapt, manage complexity, structure your own behavior, etc. ! Measured by “IQ Tests” - Intelligence Quotient (e.g., WAIS-IV, WISC-IV, Cattell Culture Fair III, Woodcock-Johnson Tests of Cognitive Abilities-III, Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scales V) ! IQ once thought to be unitary construct; now best represented by multiple domains. For example, on the WISC IV ! Verbal Comprehension (VC) Index ! Perceptual Reasoning (PO) Index ! Processing Speed (PS) Index ! Working Memory (WM) Index ! IQ once thought to be stable; now we are coming to see that skills within IQ may be trained (e.g., Working Memory) Intelligence vs. Achievement ! Achievement ! “What a child has learned so far…” in various subjects ! Reading ! Math ! Written Language ! Assessment measures– Woodcock Johnson Tests of Achievement WJ-III, Wechsler Individual Achievement Test – WIAT, Wide Range Achievement Test (WRAT) ! IQ and Achievement generally correlated ! High IQ expect High Achievement ! Avg. -

Investigating the Effectiveness of the Brain Age Software for Nintendo DS Shaun Michael English Marquette University

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by epublications@Marquette Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette Dissertations (2009 -) Dissertations, Theses, and Professional Projects Cognitive Training With Healthy Older Adults: Investigating the Effectiveness of the Brain Age Software for Nintendo DS Shaun Michael English Marquette University Recommended Citation English, Shaun Michael, "Cognitive Training With Healthy Older Adults: Investigating the Effectiveness of the Brain Age Software for Nintendo DS" (2012). Dissertations (2009 -). Paper 226. http://epublications.marquette.edu/dissertations_mu/226 COGNITIVE TRAINING WITH HEALTHY OLDER ADULTS: INVESTIGATING THE EFFECTIVENESS OF THE BRAIN AGETM SOFTWARE FOR NINTENDO By Shaun M. English, M.S. A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School, Marquette University, In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Milwaukee, Wisconsin October 2012 ABSTRACT COGNITIVE TRAINING WITH HEALTHY OLDER ADULTS: INVESTIGATING THE EFFECTIVENESS OF THE BRAIN AGETM SOFTWARE FOR NINTENDO Shaun M. English, M.S. Marquette University, 2012 An increasing number of empirical studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of cognitive training (CT) with healthy, cognitively intact older adults. Less is known regarding the effectiveness of commercially available “brain training” programs. The current study investigated the impact of daily CT presented via the Brain Age® software for Nintendo DS on neurocognitive abilities in a sample of healthy, community-dwelling older adults. Over the six-week study, participants in the CT group completed training activities and were compared to an active control group who played card games on the Nintendo DS. At pre-test and post-test, a wide range of empirically validated neuropsychological outcome measures was administered to examine the proximal and distal transfer effects of training. -

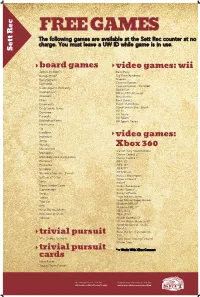

Sett Rec Counter at No Charge

FREE GAMES The following games are available at the Sett Rec counter at no charge. You must leave a UW ID while game is in use. Sett Rec board games video games: wii Apples to Apples Bash Party Backgammon Big Brain Academy Bananagrams Degree Buzzword Carnival Games Carnival Games - MiniGolf Cards Against Humanity Mario Kart Catchphrase MX vs ATV Untamed Checkers Ninja Reflex Chess Rock Band 2 Cineplexity Super Mario Bros. Crazy Snake Game Super Smash Bros. Brawl Wii Fit Dominoes Wii Music Eurorails Wii Sports Exploding Kittens Wii Sports Resort Finish Lines Go Headbanz Imperium video games: Jenga Malarky Mastermind Xbox 360 Call of Duty: World at War Monopoly Dance Central 2* Monopoly Deal (card game) Dance Central 3* Pictionary FIFA 15* Po-Ke-No FIFA 16* Scrabble FIFA 17* Scramble Squares - Parrots FIFA Street Forza 2 Motorsport Settlers of Catan Gears of War 2 Sorry Halo 4 Super Jumbo Cards Kinect Adventures* Superfection Kinect Sports* Swap Kung Fu Panda Taboo Lego Indiana Jones Toss Up Lego Marvel Super Heroes Madden NFL 09 Uno Madden NFL 17* What Do You Meme NBA 2K13 Win, Lose or Draw NBA 2K16* Yahtzee NCAA Football 09 NCAA March Madness 07 Need for Speed - Rivals Portal 2 Ruse the Art of Deception trivial pursuit SSX 90's, Genus, Genus 5 Tony Hawk Proving Ground Winter Stars* trivial pursuit * = Works With XBox Connect cards Harry Potter Young Players Edition Upcoming Events in The Sett Program your own event at The Sett union.wisc.edu/sett-events.aspx union.wisc.edu/eventservices.htm. -

Cognitive Training with Healthy Older Adults: Investigating the Effectiveness of the Brain Age Software for Nintendo DS

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette Dissertations, Theses, and Professional Dissertations (1934 -) Projects Cognitive Training With Healthy Older Adults: Investigating the Effectiveness of the Brain Age Software for Nintendo DS Shaun Michael English Marquette University Follow this and additional works at: https://epublications.marquette.edu/dissertations_mu Part of the Psychiatry and Psychology Commons Recommended Citation English, Shaun Michael, "Cognitive Training With Healthy Older Adults: Investigating the Effectiveness of the Brain Age Software for Nintendo DS" (2012). Dissertations (1934 -). 226. https://epublications.marquette.edu/dissertations_mu/226 COGNITIVE TRAINING WITH HEALTHY OLDER ADULTS: INVESTIGATING THE EFFECTIVENESS OF THE BRAIN AGETM SOFTWARE FOR NINTENDO By Shaun M. English, M.S. A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School, Marquette University, In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Milwaukee, Wisconsin October 2012 ABSTRACT COGNITIVE TRAINING WITH HEALTHY OLDER ADULTS: INVESTIGATING THE EFFECTIVENESS OF THE BRAIN AGETM SOFTWARE FOR NINTENDO Shaun M. English, M.S. Marquette University, 2012 An increasing number of empirical studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of cognitive training (CT) with healthy, cognitively intact older adults. Less is known regarding the effectiveness of commercially available “brain training” programs. The current study investigated the impact of daily CT presented via the Brain Age® software for Nintendo DS on neurocognitive abilities in a sample of healthy, community-dwelling older adults. Over the six-week study, participants in the CT group completed training activities and were compared to an active control group who played card games on the Nintendo DS. At pre-test and post-test, a wide range of empirically validated neuropsychological outcome measures was administered to examine the proximal and distal transfer effects of training. -

Nintendo Co., Ltd

Nintendo Co., Ltd. Financial Results Briefing for the Nine-Month Period Ended December 2007 (Briefing Date: 2008/1/25) Supplementary Information [Note] Forecasts announced by Nintendo Co., Ltd. herein are prepared based on management's assumptions with information available at this time and therefore involve known and unknown risks and uncertainties. Please note such risks and uncertainties may cause the actual results to be materially different from the forecasts (earnings forecast, dividend forecast and other forecasts). Nintendo Co., Ltd. Consolidated Statements of Income Transition million yen FY3/2004 FY3/2005 FY3/2006 FY3/2007 FY3/2008 Apr.-Dec.'03 Apr.-Dec.'04 Apr.-Dec.'05 Apr.-Dec.'06 Apr.-Dec.'07 Net sales 439,589 419,373 412,339 712,589 1,316,434 Cost of sales 257,524 232,495 237,322 411,862 761,944 Gross margin 182,064 186,877 175,017 300,727 554,489 (Gross margin ratio) (41.4%) (44.6%) (42.4%) (42.2%) (42.1%) Selling, general, and administrative expenses 79,436 83,771 92,233 133,093 160,453 Operating income 102,627 103,106 82,783 167,633 394,036 (Operating income ratio) (23.3%) (24.6%) (20.1%) (23.5%) (29.9%) Other income 8,837 15,229 64,268 53,793 37,789 (of which foreign exchange gains) ( - ) (4,778) (45,226) (26,069) (143) Other expenses 59,175 2,976 357 714 995 (of which foreign exchange losses) (58,805) ( - ) ( - ) ( - ) ( - ) Income before income taxes and extraordinary items 52,289 115,359 146,694 220,713 430,830 (Income before income taxes and extraordinary items ratio) (11.9%) (27.5%) (35.6%) (31.0%) (32.7%) Extraordinary gains 2,229 1,433 6,888 1,047 3,830 Extraordinary losses 95 1,865 255 27 2,135 Income before income taxes and minority interests 54,423 114,927 153,327 221,734 432,525 Income taxes 19,782 47,260 61,176 89,847 173,679 Minority interests 94 -91 -34 -29 -83 Net income 34,545 67,757 92,185 131,916 258,929 (Net income ratio) (7.9%) (16.2%) (22.4%) (18.5%) (19.7%) - 1 - Nintendo Co., Ltd. -

Brain Exercises Mobile

Dr. Erin Keeps You Informed and right side of the brain. Crawling is as vital in stimulating brain growth as it is in helping a child be Brain Exercises mobile. In fact, it’s more important. For All Ages Studies have found that not only can avoiding crawling cause learning difficulties in reading, writing and We all know that exercise is good for our bodies; we comprehension, but even speech can be affected if the can promote good health and stay fit if we exercise crawling stage of development is skipped. regularly. What you may not know, is that the same is true for the brain. If an infant has gone from rolling over to using objects to creep along in a standing position, it’s important to Just like any other muscle, the brain can get in shape, take the child down from the furniture and encourage be strengthened and developed with use or exercise. them to crawl. What About the Brain? Children and Pre-Adolescents The human brain is made up of nerve cells called Obviously, children and pre-adolescents are going to neurons and these are connected by synapses which benefit from brain games that encourage them to transport information from one neuron to the other. Just like other muscles and organs, the brain does change with age; synapses fire more slowly, some cells die off “Recent studies have and the overall mass of the organ shrinks. However, advances in brain imaging and neuroscience coupled found that today’s youth with studies of twins have shown that not all change is genetically predetermined or inevitable. -

Usaa Fund Holdings Usaa High Income Fund

USAA FUND HOLDINGS As of September 30, 2020 USAA HIGH INCOME FUND CUSIP TICKER SECURITY NAME SHARES/PAR/CONTRACTS MARKET VALUE 00105DAF2 AES VRN 3/26/2079 5,000,000.00 5,136,700.00 001846AA2 ANGI 3.875% 8/15/28 100,000.00 99,261.00 00206R102 T AT&T, INC. 33,780.00 963,067.80 00287Y109 ABBV ABBVIE INC. 22,300.00 1,953,257.00 00687YAA3 ADIENT GL 4.875% 08/15/26 10,000,000.00 9,524,000.00 00774MAB1 AERCAP IE 3.65% 07/21/27 5,000,000.00 4,575,600.00 00790RAA2 ADVANCED 5.00% 09/30/27 1,000,000.00 1,044,910.00 009089AA1 AIR CANAD 4.125% 11/15/26 5,485,395.25 4,928,079.09 01166VAA7 ALASKA 4.80% 2/15/29 2,000,000.00 2,092,020.00 013092AG6 ALBERTSON 3.5% 03/15/29 1,000,000.00 970,120.00 013093AD1 ALBERTSONS 5.75% 3/15/25 9,596,000.00 9,917,370.04 013817AK7 ARCONIC 5.95% 02/01/37 5,000,000.00 5,359,250.00 013822AC5 ALCOA NED 6.125% 5/15/28 4,000,000.00 4,213,680.00 016900AC6 ALLEGHENY 6.95% 12/15/25 6,456,000.00 6,418,361.52 01741RAH5 ALLEGHENY 5.875% 12/01/27 500,000.00 480,715.00 01879NAA3 ALLIANCE 7.5% 05/01/25 3,000,000.00 2,129,100.00 02154CAF0 ALTICE FI 5.00% 01/15/28 5,000,000.00 4,855,050.00 02156LAA9 ALTICE FR 8.125% 02/01/27 6,000,000.00 6,536,940.00 02156TAA2 ALTICE 6.00% 02/15/28 10,000,000.00 9,518,800.00 031921AA7 AMWINS GR 7.75% 07/01/26 4,000,000.00 4,282,040.00 032359AE1 AMTRUST F 6.125% 08/15/23 9,760,000.00 8,937,817.60 037411BE4 APACHE 4.375% 10/15/28 10,000,000.00 9,131,000.00 03938LAP9 ARCELORMI 7.% 10/15/39 8,000,000.00 10,121,280.00 03966VAA5 ARCONIC 6.125% 02/15/28 1,200,000.00 1,234,896.00 03966VAB3 ARCONIC 6.00% 05/15/2025 -

Physical Address A+ FEDERAL CREDIT UNION (512)302-6800 ATTN: LOAN PAYOFF 6420 US HWY

PAYOFF ADDRESS Lender Phone Number(s) Physical Address A+ FEDERAL CREDIT UNION (512)302-6800 ATTN: LOAN PAYOFF 6420 US HWY 290 E AUSTIN, TX 78723 ALLY AUTO FINANCE/GMAC (888)925-2559 ATTN: PAYMENT PROCESSING 6716 GRADE LN BLDG 9 STE 910 LOUISVILLE, KY 40213-3416 AMERICREDIT (800)365-3635 4001 EMBARCADERO DR ARILNGTON, TX 76014 AMPLIFY FEDERAL CREDIT UNION (512)836-5901 ATTN: LOAN PAYOFF 2608 BROCKTON DR. STE 105 AUSTIN, TX 78758 AUDI FINANCIAL (800)428-4034 1401 FRANKLIN BLVD LIBERTYVILLE, IL 60048 AUSTIN FEDERAL CREDIT UNION (512)444-6419 1900 WOODWARD AUSTIN, TX 78741 AUSTIN TELCO FEDERAL CREDIT UNION (512)302-5555 ATTN: LOAN PAYOFF 8929 SHOAL CREEK BLVD STE 100 AUSTIN, TX 78757 BANK OF AMERICA (800)215-6195 9000 SOUTHSIDE BLVD BLVD BLDG 600 JACKSONVILLE, FL 32256 BANK OF THE WEST (800)827-7500 1450 TREAT BLVD WALNUT CREEK, CA 94597 BRAZOS VALLEY SCHOOL CREDIT UNION (281)391-2149 438 F M 1463 KATY, TX 77494 CAPITAL CREDIT UNION (512)477-9465 1718 LAVACA ST FAX: (512)477-9466 AUSTIN, TX 78701 CAPITAL ONE AUTO FINANCE (800)946-0332 ATTN: PAYMENT PROCESSING 2525 CORPORATE PLACE 2ND FLOOR STE 250 MONTEREY PARK, CA 91754 CAPITOL CREDIT UNION (800)486-4228 11902-A BURNET RD AUSTIN, TX 78758 CARMAX AUTO FINANCE (800)925-3612 ATTN: PAYOFF DEPARTMENT 225 CHASTAIN MEADOWS COURT STE 210 KENNESAW, GA 30144 CENTER ONE FINANCIAL (866)636-8575 190 J IM MORAN BLVD DEERFIELD BEACH, FL 33442 CHASE AUTO FINANCE (800)336-6675 14800 FRY RD 1ST FLOOR TX-1300 FT WORTH, TX 76155 CITIFINANCIAL AUTO (800)486-1750 1500 BOLTONFIELD ST COLUMBUS, OH 43228 COMPASS BANK (800)239-1996 701 32ND ST SOUTH BIRMINGHAM, AL 35233 CREDI T UNION OF TEXAS (972)63-9497 4600 ROSS AVE DALLAS, TX 75204 DRIVE TIME ACCEPTANCE (800)967-8526 7300 E. -

Oil & Gas Companies, AT&T Affiliated Pacs, USAA, and San Antonio

Oil & Gas Companies, AT&T Affiliated PACs, USAA, And San Antonio Spurs Leadership Are Among The Top Corporate Donors To The 15 Conservative Texas Lawmakers That Advanced Voting Restrictions Over The Weekend Of July 10th Top Corporate Donors Of The Six Conservative Members Of The Texas Senate State Affairs Committee—The Senate Committee Which Already Advanced Voting Restriction Bill SB1 During Texas’ Special Session— Include Texas Oil Moguls, AT&T Affiliated PACs, San Antonio Spurs Leadership, And Other Corporate Entities In 2021, The Texas Senate State Affairs Committee Advanced Senate Bill 7 (SB 7), A Voting Restrictions Bill That Legislators Later Killed By Walking Out Of The Regular Legislative Session—Now, Legislators Are Considering Similar Legislation During A July 2021 Special Session In 2021, The Texas Senate State Affairs Committee Advanced Texas’ Senate Bill 7 (SB 7), A Bill That Would Curb Early Voting Hours, Give “Alarming” Power To Poll Watchers, And Limit Voting Options That Were “Especially Effective Last Year In Reaching Voters Of Color” The Senate State Affairs Committee Advanced Texas’ Senate Bill 7 (SB 7) In 2021. [Texas Legislature, accessed 07/08/21] SB 7 Was “Best Known For Curbing Early Voting Hours And Banning 24-Hour Voting And Drive Through Voting.” “Amid the heated presidential race last fall, Texas polling places experienced ‘a surge in voter intimidation,’ according to the Texas Civil Rights Project. The group received 267 complaints from around the state. Many involved demonstrators shouting at voters outside of polling places, an escalation of harassment that local election officials in 2018 described as the worst they had seen in decades.