Beyond Memory"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

County Theater ART HOUSE

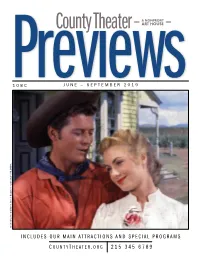

A NONPROFIT County Theater ART HOUSE Previews108C JUNE – SEPTEMBER 2019 Gordon MacRae and Shirley Jones in Rodgers & Hammerstein’s OKLAHOMA! & Hammerstein’s in Rodgers Gordon MacRae and Shirley Jones INCLUDES OUR MAIN ATTRACTIONS AND SPECIAL PROGRAMS C OUNTYT HEATER.ORG 215 345 6789 Welcome to the nonprofit County Theater The County Theater is a nonprofit, tax-exempt 501(c)(3) organization. Policies ADMISSION Children under 6 – Children under age 6 will not be admitted to our films or programs unless specifically indicated. General ............................................................$11.25 Late Arrivals – The Theater reserves the right to stop selling Members ...........................................................$6.75 tickets (and/or seating patrons) 10 minutes after a film has Seniors (62+) & Students ..................................$9.00 started. Matinees Outside Food and Drink – Patrons are not permitted to bring Mon, Tues, Thurs & Fri before 4:30 outside food and drink into the theater. Sat & Sun before 2:30 .....................................$9.00 Wed Early Matinee before 2:30 ........................$8.00 Accessibility & Hearing Assistance – The County Theater has wheelchair-accessible auditoriums and restrooms, and is Affiliated Theater Members* ...............................$6.75 equipped with hearing enhancement headsets and closed cap- You must present your membership card to obtain membership discounts. tion devices. (Please inquire at the concession stand.) The above ticket prices are subject to change. Parking Check our website for parking information. THANK YOU MEMBERS! Your membership is the foundation of the theater’s success. Without your membership support, we would not exist. Thank you for being a member. Contact us with your feedback How can you support or questions at 215 348 1878 x115 or email us at COUNTY THEATER the County Theater? MEMBER [email protected]. -

PDF Download in a Lonely Place Pdf Free Download

IN A LONELY PLACE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Dorothy B. Hughes | 192 pages | 06 May 2010 | Penguin Books Ltd | 9780141192314 | English | London, United Kingdom In a Lonely Place PDF Book This is a crisp black-and-white film with an almost ruthless efficiency of style. But what of the real thing? Guy Beach Swan. Well, if that's not wrapping it up with a nice pink ribbon, I don't know what is; and, as I came closer and closer to the end of it I said, 'Well, today is the day and I have to be ready. February 11, Concert. Yet perhaps they all sensed that they were doing the best work of their careers -- a film could be based on those three people and that experience. Now it doesn't matter Power pop , alternative rock. Short Takes — Nov 18, Thanks to the Whitney museum, the floating garden made it onto the water for a week in That ideal of simmering rapport underlies their first exchanges of glance and gaze and repartee, cinematically framed by the courtyard of their Spanish-style apartment complex. He starts writing again. As befits a film about a screenwriter, the film is intriguingly self-aware. A tour de force laying open the mind and motives of a killer with extraordinary empathy. But what makes this a heartbreaking tragedy instead of a jaded satire is that, beneath its bruised pessimism, the film still clings to the hope that art and integrity and love can survive in the wasteland—a hope that dies slowly, agonizingly before our eyes. -

31 Days of Oscar® 2010 Schedule

31 DAYS OF OSCAR® 2010 SCHEDULE Monday, February 1 6:00 AM Only When I Laugh (’81) (Kevin Bacon, James Coco) 8:15 AM Man of La Mancha (’72) (James Coco, Harry Andrews) 10:30 AM 55 Days at Peking (’63) (Harry Andrews, Flora Robson) 1:30 PM Saratoga Trunk (’45) (Flora Robson, Jerry Austin) 4:00 PM The Adventures of Don Juan (’48) (Jerry Austin, Viveca Lindfors) 6:00 PM The Way We Were (’73) (Viveca Lindfors, Barbra Streisand) 8:00 PM Funny Girl (’68) (Barbra Streisand, Omar Sharif) 11:00 PM Lawrence of Arabia (’62) (Omar Sharif, Peter O’Toole) 3:00 AM Becket (’64) (Peter O’Toole, Martita Hunt) 5:30 AM Great Expectations (’46) (Martita Hunt, John Mills) Tuesday, February 2 7:30 AM Tunes of Glory (’60) (John Mills, John Fraser) 9:30 AM The Dam Busters (’55) (John Fraser, Laurence Naismith) 11:30 AM Mogambo (’53) (Laurence Naismith, Clark Gable) 1:30 PM Test Pilot (’38) (Clark Gable, Mary Howard) 3:30 PM Billy the Kid (’41) (Mary Howard, Henry O’Neill) 5:15 PM Mr. Dodd Takes the Air (’37) (Henry O’Neill, Frank McHugh) 6:45 PM One Way Passage (’32) (Frank McHugh, William Powell) 8:00 PM The Thin Man (’34) (William Powell, Myrna Loy) 10:00 PM The Best Years of Our Lives (’46) (Myrna Loy, Fredric March) 1:00 AM Inherit the Wind (’60) (Fredric March, Noah Beery, Jr.) 3:15 AM Sergeant York (’41) (Noah Beery, Jr., Walter Brennan) 5:30 AM These Three (’36) (Walter Brennan, Marcia Mae Jones) Wednesday, February 3 7:15 AM The Champ (’31) (Marcia Mae Jones, Walter Beery) 8:45 AM Viva Villa! (’34) (Walter Beery, Donald Cook) 10:45 AM The Pubic Enemy -

Lonely Places, Dangerous Ground

Introduction Nicholas Ray and the Potential of Cinema Culture STEVEN RYBIN AND WILL SCHEIBEL THE DIRECTOR OF CLASSIC FILMS SUCH AS They Live by Night, In a Lonely Place, Johnny Guitar, Rebel Without a Cause, and Bigger Than Life, among others, Nicholas Ray was the “cause célèbre of the auteur theory,” as critic Andrew Sarris once put it (107).1 But unlike his senior colleagues in Hollywood such as Alfred Hitchcock or Howard Hawks, he remained a director at the margins of the American studio system. So too has he remained at the margins of academic film scholarship. Many fine schol‑ arly works on Ray, of course, have been published, ranging from Geoff Andrew’s important auteur study The Films of Nicholas Ray: The Poet of Nightfall and Bernard Eisenschitz’s authoritative biography Nicholas Ray: An American Journey (both first published in English in 1991 and 1993, respectively) to books on individual films by Ray, such as Dana Polan’s 1993 monograph on In a Lonely Place and J. David Slocum’s 2005 col‑ lection of essays on Rebel Without a Cause. In 2011, the year of his centennial, the restoration of his final film,We Can’t Go Home Again, by his widow and collaborator Susan Ray, signaled renewed interest in the director, as did the publication of a new biography, Nicholas Ray: The Glorious Failure of an American Director, by Patrick McGilligan. Yet what Nicholas Ray’s films tell us about Classical Hollywood cinema, what it was and will continue to be, is far from certain. 1 © 2014 State University of New York Press, Albany 2 Steven Rybin and Will Scheibel After all, what most powerfully characterizes Ray’s films is not only what they are—products both of Hollywood’s studio and genre systems—but also what they might be. -

Elizabeth Taylor: Screen Goddess

PRESS RELEASE: June 2011 11/5 Elizabeth Taylor: Screen Goddess BFI Southbank Salutes the Hollywood Legend On 23 March 2011 Hollywood – and the world – lost a living legend when Dame Elizabeth Taylor died. As a tribute to her BFI Southbank presents a season of some of her finest films, this August, including Giant (1956), Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (1958) and Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1966). Throughout her career she won two Academy Awards and was nominated for a further three, and, beauty aside, was known for her humanitarian work and fearless social activism. Elizabeth Taylor was born in Hampstead, London, on 27 February 1932 to affluent American parents, and moved to the US just months before the outbreak of WWII. Retired stage actress Sara Southern doggedly promoted her daughter’s career as a child star, culminating in the hit National Velvet (1944), when she was just 12, and was instrumental in the reluctant teenager’s successful transition to adult roles. Her first big success in an adult role came with Vincente Minnelli’s Father of the Bride (1950), before her burgeoning sexuality was recognised and she was cast as a wealthy young seductress in A Place in the Sun (1951) – her first on-screen partnership with Montgomery Clift (a friend to whom Taylor remained fiercely loyal until Clift’s death in 1966). Together they were hailed as the most beautiful movie couple in Hollywood history. The oil-epic Giant (1956) came next, followed by Raintree County (1958), which earned the actress her first Oscar nomination and saw Taylor reunited with Clift, though it was during the filming that he was in the infamous car crash that would leave him physically and mentally scarred. -

El Cid and the Circumfixion of Cinematic History: Stereotypology/ Phantomimesis/ Cryptomorphoses

9780230601253ts04.qxd 03/11/2010 08:03 AM Page 75 Chapter 2 The Passion of El Cid and the Circumfixion of Cinematic History: Stereotypology/ Phantomimesis/ Cryptomorphoses I started with the final scene. This lifeless knight who is strapped into the saddle of his horse ...it’s an inspirational scene. The film flowed from this source. —Anthony Mann, “Conversation with Anthony Man,” Framework 15/16/27 (Summer 1981), 191 In order, therefore, to find an analogy, we must take flight into the misty realm of religion. —Karl Marx, Capital, 165 It is precisely visions of the frenzy of destruction, in which all earthly things col- lapse into a heap of ruins, which reveal the limit set upon allegorical contempla- tion, rather than its ideal quality. The bleak confusion of Golgotha, which can be recognized as the schema underlying the engravings and descriptions of the [Baroque] period, is not just a symbol of the desolation of human existence. In it transitoriness is not signified or allegorically represented, so much as, in its own significance, displayed as allegory. As the allegory of resurrection. —Walter Benjamin, The Origin of German Tragic Drama, 232 The allegorical form appears purely mechanical, an abstraction whose original meaning is even more devoid of substance than its “phantom proxy” the allegor- ical representative; it is an immaterial shape that represents a sheer phantom devoid of shape and substance. —Paul de Man, Blindness and Insight, 191–92 Destiny Rides Again The medieval film epic El Cid is widely regarded as a liberal film about the Cold War, in favor of détente, and in support of civil rights and racial 9780230601253ts04.qxd 03/11/2010 08:03 AM Page 76 76 Medieval and Early Modern Film and Media equality in the United States.2 This reading of the film depends on binary oppositions between good and bad Arabs, and good and bad kings, with El Cid as a bourgeois male subject who puts common good above duty. -

Martin Ritt 19:00 PROVIDENCE - Alain Resnais 21:00 the FAN - Ed Bianchi

Domingo 9 17:00 THE SPY WHO CAME IN FROM THE COLD - Martin Ritt 19:00 PROVIDENCE - Alain Resnais 21:00 THE FAN - Ed Bianchi Lunes 10 CGAC 17:00 L’AVEU - Constantin Costa-Gavras 19:30 L’AMOUR À MORT - Alain Resnais 21:15 THE RAIN PEOPLE - Francis Ford Coppola Martes 11 17:00 A DANDY IN ASPIC - Anthony Mann, Laurence Harvey 19:00 THE DEADLY AFFAIR - Sidney Lumet 21:00 DER HIMMEL ÜBER BERLIN - Wim Wenders Miércoles 12 16:30 SECHSE KOMMEN DURCH DIE WELT - Rainer Simon 18:00 TILL EULENSPIEGEL - Rainer Simon 19:45 JADUP UND BOEL - Rainer Simon 21:30 DIE FRAU UND DER FREMDE - Rainer Simon Jueves 13 17:45 WENGLER & SÖHNE, EINE LEGENDE - Rainer Simon 19:30 DER FALL Ö - Rainer Simon 21:15 WORK IN PROGRESS: CORTOMETRAJES DE MARCOS NINE - Marcos Nine Viernes 14 16:00 FÜNF PATRONENHÜLSEN - Frank Beyer 17:30 NACKT UNTER WÖLFEN - Frank Beyer 19:45 KARBID UND SAUERAMPFER - Frank Beyer 21:15 JAKOB, DER LÜGNER - Frank Beyer 23:00 DER VERDACHT - Frank Beyer Miércoles 19 21:30 DER TUNNEL - Roland Suso Richter Jueves 20 16:00 CARLOS - Olivier Assayas 21:45 DIE STILLE NACH DEM SCHUSS - Volker Schlöndorff Venres 21 16:00 8MM-KO ERREPIDEA - Tximino Kolektiv (Ander Parody, Pablo Maraví, Itxaso Koto, Mikel Armendáriz) 17:00 PROXECTO NIMBOS (SELECCIÓN DE CORTOMETRAJES) - Varios autores 17:45 WORK IN PROGRESS: O LUGAR DOS AVÓS - Víctor Hugo Seoane 20:15 EL CORRAL Y EL VIENTO - Miguel Hilari 21:15 OUROBOROS - Carlos Rivero, Alonso Valbuena Sábado 22 17:00 VIDEOCREACIÓNS - Olalla Castro 18:30 A HISTÓRIA DE UM ERRO - Joana Barros 20:15 TRUE ROMANCE. -

Movie Museum FEBRUARY 2009 COMING ATTRACTIONS

Movie Museum FEBRUARY 2009 COMING ATTRACTIONS THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY MONDAY VICKY CRISTINA IN BRUGES BOTTLE SHOCK ARSENIC AND IN BRUGES BARCELONA (2008-UK/Belgium) (2008) OLD LACE (2008-UK/Belgium) (2008-Spain/US) in widescreen in widescreen in widescreen in Catalan/English/Spanish w/ (1944) with Chris Pine, Alan with Cary Grant, Josephine English subtitles in widescreen with Colin Farrell, Brendan with Colin Farrell, Brendan Hull, Jean Adair, Raymond with Rebecca Hall, Scarlett Gleeson, Ralph Fiennes, Rickman, Bill Pullman, Gleeson, Ralph Fiennes, Johansson, Javier Bardem, Clémence Poésy, Eric Godon, Rachael Taylor, Freddy Massey, Peter Lorre, Priscilla Clémence Poésy, Eric Godon, Penelopé Cruz, Chris Ciarán Hinds. Rodriguez, Dennis Farina. Lane, John Alexander, Jack Ciarán Hinds. Messina, Patricia Clarkson. Carson, John Ridgely. Written and Directed by Written and Directed by Directed and Co-written by Written and Directed by Woody Allen. Martin McDonagh. Randall Miller. Directed by Martin McDonagh. Frank Capra. 12:30, 2:30, 4:30, 6:30 12:30, 2:30, 4:30, 6:30 12:30, 2:30, 4:30, 6:30 12:30, 2:30, 4:30, 6:30 & 8:30pm 5 & 8:30pm 6 & 8:30pm 7 12:30, 3, 5:30 & 8pm 8 & 8:30pm 9 Lincoln's 200th Birthday THE VISITOR Valentine's Day THE VISITOR Presidents' Day 2 for 1 YOUNG MR. LINCOLN (2007) OUT OF AFRICA (2007) THE TALL TARGET (1951) (1939) in widescreen (1985) in widescreen with Dick Powell, Paula Raymond, Adolphe Menjou. with Henry Fonda, Alice with Richard Jenkins, Haaz in widescreen with Richard Jenkins, Haaz Directed by Anthony Mann. -

<I>In a Lonely Place</I>, Directed by Nicholas Ray, USA, 1950*

9-Arts Reviews_CAFP_9.qxp 15/02/2019 10:10 Page 86 ARTS REVIEWS In a Lonely Place, directed by Nicholas Ray, USA, 1950* Reviewed by Ann Hardy One autumn night, a score of therapists met to watch a film that was older than most of them. In a Lonely Place is the story of a brief relationship between screenwriter and war veteran, Dixon (“Dix”) Steele (Humphrey Bogart) and his glamorous and sophisticated neighbour, actress Laurel Gray (Gloria Grahame). Shot in black and white, the film is spare: in a few short minutes we meet Dix and discover that he has not been able to write anything original since before the war, surviving by churning out screenplays of popular novels. We also learn that he is violent; indeed we see him in a number of fights, and are told that he broke the nose of a previous lover. His justification for his violence is always the same: “They had it coming.” Here is a man who is dangerous, but all that is bad is projected outwards. The story develops when Dix is suspected of murdering Mildred Atkinson, a naïve young woman, who lives with her aunt, and checks coats at Dix’s favourite bar. Dix invites Mildred to his apartment to tell him the story of a novel for which he has to write the screenplay, but which he is too apathetic to read. The next morning Mildred is found dead and Dix is taken to the police station for questioning. He is released when an alibi is provided by Laurel, who has just moved into the apartment opposite, and who saw Mildred leave. -

Smoothing the Wrinkles Hollywood, “Successful Aging” and the New Visibility of Older Female Stars Josephine Dolan

Template: Royal A, Font: , Date: 07/09/2013; 3B2 version: 9.1.406/W Unicode (May 24 2007) (APS_OT) Dir: //integrafs1/kcg/2-Pagination/TandF/GEN_RAPS/ApplicationFiles/9780415527699.3d 31 Smoothing the wrinkles Hollywood, “successful aging” and the new visibility of older female stars Josephine Dolan For decades, feminist scholarship has consistently critiqued the patriarchal underpinnings of Hollywood’s relationship with women, in terms of both its industrial practices and its representational systems. During its pioneering era, Hollywood was dominated by women who occupied every aspect of the filmmaking process, both off and on screen; but the consolidation of the studio system in the 1920s and 1930s served to reduce the scope of opportunities for women working in off-screen roles. Off screen, a pattern of gendered employment was effectively established, one that continues to confine women to so-called “feminine” crafts such as scriptwriting and costume. Celebrated exceptions like Ida Lupino, Dorothy Arzner, Norah Ephron, Nancy Meyers, and Katherine Bigelow have found various ways to succeed as producers and directors in Hollywood’s continuing male-dominated culture. More typically, as recently as 2011, “women comprised only 18% of directors, executive producers, cinematographers and editors working on the top 250 domestic grossing films” (Lauzen 2012: 1). At the same time, on-screen representations came to be increasingly predicated on a gendered star system that privileges hetero-masculine desires, and are dominated by historically specific discourses of idealized and fetishized feminine beauty that, in turn, severely limit the number and types of roles available to women. As far back as 1973 Molly Haskell observed that the elision of beauty and youth that underpins Hollywood casting impacted upon the professional longevity of female stars, who, at the first visible signs of aging, were deemed “too old or over-ripe for a part,” except as a marginalized mother or older sister. -

Film Noir - Danger, Darkness and Dames

Online Course: Film Noir - Danger, Darkness and Dames WRITTEN BY CHRIS GARCIA Welcome to Film Noir: Danger, Darkness and Dames! This online course was written by Chris Garcia, an Austin American-Statesman Film Critic. The course was originally offered through Barnes & Noble's online education program and is now available on The Midnight Palace with permission. There are a few ways to get the most out of this class. We certainly recommend registering on our message boards if you aren't currently a member. This will allow you to discuss Film Noir with the other members; we have a category specifically dedicated to noir. Secondly, we also recommend that you purchase the following books. They will serve as a companion to the knowledge offered in this course. You can click each cover to purchase directly. Both of these books are very well written and provide incredible insight in to Film Noir, its many faces, themes and undertones. This course is structured in a way that makes it easy for students to follow along and pick up where they leave off. There are a total of FIVE lessons. Each lesson contains lectures, summaries and an assignment. Note: this course is not graded. The sole purpose is to give students a greater understanding of Dark City, or, Film Noir to the novice gumshoe. Having said that, the assignments are optional but highly recommended. The most important thing is to have fun! Enjoy the course! Jump to a Lesson: Lesson 1, Lesson 2, Lesson 3, Lesson 4, Lesson 5 Lesson 1: The Seeds of Film Noir, and What Noir Means Social and artistic developments forged a new genre. -

Chronology and Itinerary of the Career of J. Tim Brymn Materials for a Biography Peter M

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications: School of Music Music, School of 8-26-2016 Chronology and Itinerary of the Career of J. Tim Brymn Materials for a Biography Peter M. Lefferts University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicfacpub Part of the African American Studies Commons, American Popular Culture Commons, and the Music Commons Lefferts, Peter M., "Chronology and Itinerary of the Career of J. Tim Brymn Materials for a Biography" (2016). Faculty Publications: School of Music. 64. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicfacpub/64 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Music, School of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications: School of Music by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. 1 08/26/2016 Chronology and Itinerary of the Career of J. Tim Brymn Materials for a Biography Peter M. Lefferts University of Nebraska-Lincoln This document is one in a series---"Chronology and Itinerary of the Career of"---devoted to a small number of African American musicians active ca. 1900-1950. They are fallout from my work on a pair of essays, "US Army Black Regimental Bands and The Appointments of Their First Black Bandmasters" (2013) and "Black US Army Bands and Their Bandmasters in World War I" (2012/2016). In all cases I have put into some kind of order a number of biographical research notes, principally drawing upon newspaper and genealogy databases. None of them is any kind of finished, polished document; all represent work in progress, complete with missing data and the occasional typographical error.