Revenge Porn and Tort Remedies for Public Figures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Constitution and Revenge Porn

Pace Law Review Volume 35 Issue 1 Fall 2014 Article 8 Symposium: Social Media and Social Justice September 2014 The Constitution and Revenge Porn John A. Humbach Pace University School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/plr Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, Criminal Law Commons, First Amendment Commons, Internet Law Commons, Law and Society Commons, and the Legal Remedies Commons Recommended Citation John A. Humbach, The Constitution and Revenge Porn, 35 Pace L. Rev. 215 (2014) Available at: https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/plr/vol35/iss1/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Law at DigitalCommons@Pace. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pace Law Review by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Pace. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Constitution and Revenge Porn John A. Humbach* “Many are those who must endure speech they do not like, but that is a necessary cost of freedom.”1 Revenge porn refers to sexually explicit photos and videos that are posted online or otherwise disseminated without the consent of the persons shown, generally in retaliation for a romantic rebuff.2 The problem of revenge porn seems to have emerged fairly recently,3 no doubt facilitated by the widespread practice of sexting.4 In sexting, people make and send explicit pictures of themselves using digital devices.5 These devices, in their very nature, permit the pictures to be easily shared with the entire online world. Although the move from sexting to revenge porn might seem as inevitable as the shifting winds * Professor of Law at Pace University School of Law. -

DOCUMENT RESUME Dimensions of Interest and Boredom In

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 397 840 IR 018 028 AUTHOR Small, Ruth V., And Others TITLE Dimensions of Interest and Boredom in Instructional Situations. PUB DATE 96 NOTE 16p.; In: Prbceedings of Selected Research and Development Presentations at the 1996 National Convention of the Association for Educational Communications and Technology (18th, Indianapolis, IN, 1996); see IR 017 960. PUB TYPE Reports Research/Technical (143) Speeches/Conference Papers (150) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Academic Achievement; Brainstorming; Cognitive Style; College Students; Educational Strategies; Higher Education; Instructional Development; *Instructional Effectiveness; Instructional Material Evaluation; *Learning Strategies; Likert Scales; Participant Satisfaction; Questionnaires; Relevance (Education); *Stimulation; Student Attitudes; *Student Motivation; Teacher Role; Teaching Methods IDENTIFIERS ARCS Model; *Boredom; Emotions ABSTRACT Stimulating interest and reducing boredom are important goals for promoting learning achievement. This paper reviews previous research on interest and boredom in educational settings and examines their relationship to the characteristics of emotion. It also describes research which seeks to develop a model of learner interest by identifying sources of "boring" and "interesting" leaming situations through analysis of learners' descriptions. Participants is, the study were 512 undergraduate and graduate students from two universities. Descriptive responses were elicited from 350 students through brainstorming -

Applying a Discrete Emotion Perspective

AROUSAL OR RELEVANCE? APPLYING A DISCRETE EMOTION PERSPECTIVE TO AGING AND AFFECT REGULATION SARA E. LAUTZENHISER Bachelor of Science in Psychology Ashland University May 2015 Submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS IN PSYCHOLOGY At the CLEVELAND STATE UNIVERSITY May 2019 We hereby approve this thesis For SARA E. LAUTZENHISER Candidate for the Master of Arts in Experimental Research Psychology For the Department of Psychology And CLEVELAND STATE UNIVERSITY’S College of Graduate Studies by __________________________ Eric Allard, Ph.D. __________________________ Department & Date __________________________ Andrew Slifkin, Ph. D. (Methodologist) __________________________ Department & Date __________________________ Conor McLennan, Ph.D. __________________________ Department & Date __________________________ Robert Hurley, Ph. D. __________________________ Department & Date Student’s Date of Defense May 10, 2019 AROUSAL OR RELEVANCE? APPLYING A DISCRETE EMOTION PERSPECTIE TO AGING AND AFFECT REGULATION SARA E. LAUTZENHISER ABSTRACT While research in the psychology of human aging suggests that older adults are quite adept at managing negative affect, emotion regulation efficacy may depend on the discrete emotion elicited. For instance, prior research suggests older adults are more effective at dealing with emotional states that are more age-relevant/useful and lower in intensity (i.e., sadness) relative to less relevant/useful or more intense (i.e., anger). The goal of the present study was to probe this discrete emotions perspective further by addressing the relevance/intensity distinction within a broader set of negative affective states (i.e., fear and disgust, along with anger and sadness). Results revealed that participants reported relatively high levels of the intended emotion for each video, while also demonstrating significant affective recovery after the attentional refocusing task. -

About Emotions There Are 8 Primary Emotions. You Are Born with These

About Emotions There are 8 primary emotions. You are born with these emotions wired into your brain. That wiring causes your body to react in certain ways and for you to have certain urges when the emotion arises. Here is a list of primary emotions: Eight Primary Emotions Anger: fury, outrage, wrath, irritability, hostility, resentment and violence. Sadness: grief, sorrow, gloom, melancholy, despair, loneliness, and depression. Fear: anxiety, apprehension, nervousness, dread, fright, and panic. Joy: enjoyment, happiness, relief, bliss, delight, pride, thrill, and ecstasy. Interest: acceptance, friendliness, trust, kindness, affection, love, and devotion. Surprise: shock, astonishment, amazement, astound, and wonder. Disgust: contempt, disdain, scorn, aversion, distaste, and revulsion. Shame: guilt, embarrassment, chagrin, remorse, regret, and contrition. All other emotions are made up by combining these basic 8 emotions. Sometimes we have secondary emotions, an emotional reaction to an emotion. We learn these. Some examples of these are: o Feeling shame when you get angry. o Feeling angry when you have a shame response (e.g., hurt feelings). o Feeling fear when you get angry (maybe you’ve been punished for anger). There are many more. These are NOT wired into our bodies and brains, but are learned from our families, our culture, and others. When you have a secondary emotion, the key is to figure out what the primary emotion, the feeling at the root of your reaction is, so that you can take an action that is most helpful. . -

Sexual Aggression and the Civil Response, Annual Review of Civil

ANNUAL REVIEW OF CIVIL LITIGATION 2018 THE HONOURABLE MR.JUSTICE TODD L. ARCHIBALD SUPERIOR COURT OF JUSTICE (ONTARIO) # 2018 Thomson Reuters Canada NOTICE AND DISCLAIMER: All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher (Thomson Reuters Canada, a division of Thomson Reuters Canada Limited). Thomson Reuters Canada and all persons involved in the preparation and sale of this publication disclaim any warranty as to accuracy or currency of the publication. This publication is provided on the understanding and basis that none of Thomson Reuters Canada, the author/s or other persons involved in the creation of this publication shall be responsible for the accuracy or currency of the contents, or for the results of any action taken on the basis of the information contained in this publication, or for any errors or omissions contained herein. No one involved in this publication is attempting herein to render legal, accounting or other professional advice. If legal advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional should be sought. The analysis contained herein should in no way be construed as being either official or unofficial policy of any governmental body. A cataloguing record for this publication is available from Library and Archives Canada. ISBN 978-0-7798-8457-5 Scan the QR code to the right with your smartphone to send your comments regarding our products and services. Free QR Code Readers are available from your mobile device app store. -

Preventing and Fighting the Rise of Online Sextortion and Gender Based Digital Violence

European Crime Prevention Award (ECPA) Annex I – new version 2014 Please complete the template in English in compliance with the ECPA criteria contained in the RoP (Par.2 §3). General information 1. Please specify your country. Spain 2. Is this your country’s ECPA entry or an additional project? It is Spain’s ECPA entry 3. What is the title of the project? Preventing and fighting the rise of online Sextortion and Gender Based Digital Violence 4. Who is responsible for the project? Contact details. Jorge Flores, Founder and Director of PantallasAmigas. E-mail: [email protected] mobile:+34 605 72 81 21 5. Start date of the project (dd/mm/yyyy)? Is the project still running (Yes/No)? If not, please provide the end date of the project. 07/05/2009. The project is still running and is comprised of several of the following elements: awareness campaigns, interactive games, booklets and guides for teachers and educators, intervention protocols for victims, blogs and complaint forms. 6. Where can we find more information about the project? Please provide links to the project’s website or online reports or publications (preferably in English). A chapter for Harvard and UNICEF’s Digitally Connected ebook was written to explain the work on this ongoing project. The chapter is titled “Sexting: Teens, Sex, Smartphones and the Rise of Sextortion and Gender Based Digital Violence” and is available in the following link: http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2585686 The full project is at the moment available only in Spanish -

Digital Blackmail As an Emerging Tactic 2016

September 9 DIGITAL BLACKMAIL AS AN EMERGING TACTIC 2016 Digital Blackmail (DB) represents a severe and growing threat to individuals, small businesses, corporations, and government Examining entities. The rapid increase in the use of DB such as Strategies ransomware; the proliferation of variants and growth in their ease of use and acquisition by cybercriminals; weak defenses; Public and and the anonymous nature of the money trail will only increase Private Entities the scale of future attacks. Private sector, non-governmental organization (NGO), and government cybersecurity experts Can Pursue to were brought together by the Office of the Director of National Contain Such Intelligence and the Department of Homeland Security to determine emerging tactics and countermeasures associated Attacks with the threat of DB. In this paper, DB is defined as illicitly acquiring or denying access to sensitive data for the purpose of affecting victims’ behaviors. Threats may be made of lost revenue, the release of intellectual property or sensitive personnel/client information, the destruction of critical data, or reputational damage. For clarity, this paper maps DB activities to traditional blackmail behaviors and explores methods and tools, exploits, protection measures, whether to pay or not pay the ransom, and law enforcement (LE) and government points of contact for incident response. The paper also examines the future of the DB threat. Digital Blackmail as an Emerging Tactic Team Members Name Organization Caitlin Bataillon FBI Lynn Choi-Brewer -

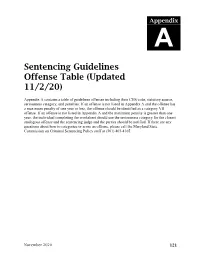

Sentencing Guidelines Offense Table (Updated 11/2/20)

Appendix A Sentencing Guidelines Offense Table (Updated 11/2/20) Appendix A contains a table of guidelines offenses including their CJIS code, statutory source, seriousness category, and penalties. If an offense is not listed in Appendix A and the offense has a maximum penalty of one year or less, the offense should be identified as a category VII offense. If an offense is not listed in Appendix A and the maximum penalty is greater than one year, the individual completing the worksheet should use the seriousness category for the closest analogous offense and the sentencing judge and the parties should be notified. If there are any questions about how to categorize or score an offense, please call the Maryland State Commission on Criminal Sentencing Policy staff at (301) 403-4165. November 2020 121 INDEX OF OFFENSES Abuse & Other Offensive Conduct ......................... 1 Kidnapping & Related Crimes .............................. 33 Accessory After the Fact ......................................... 2 Labor Trafficking ................................................... 33 Alcoholic Beverages ................................................ 2 Lotteries ................................................................. 33 Animals, Crimes Against ......................................... 3 Machine Guns ........................................................ 34 Arson & Burning ...................................................... 3 Malicious Destruction & Related Crimes ............. 34 Assault & Other Bodily Woundings ....................... -

Ambiguous Loss: a Phenomenological

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by SHAREOK repository AMBIGUOUS LOSS: A PHENOMENOLOGICAL EXPLORATION OF WOMEN SEEKING SUPPORT FOLLOWING MISCARRIAGE By KATHLEEN MCGEE Bachelor of Science in Human Development and Family Science Oklahoma State University Stillwater, Oklahoma 2011 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE May, 2014 AMBIGIOUS LOSS: A PHENOMENOLOGICAL EXPLORATION OF WOMEN SEEKING SUPPORT FOLLOWING MISCARRIAGE Thesis Approved: Dr. Kami Gallus Dr. Amanda Harrist Dr. Karina Shreffler ii Name: KATHLEEN MCGEE Date of Degree: MAY, 2014 Title of Study: AMBIGUOUS LOSS: A PHENOMENOLOGICAL EXPLORATION OF WOMEN SEEKING SUPPORT FOLLOWING MISCARRIAGE Major Field: HUMAN DEVELOPMENT AND FAMILY SCIENCE Abstract: Miscarriage is a fairly common experience that is overlooked by today’s society. Miscarriage as simply a female medical issue does not embody the full emotional toll of the experience. Research is lacking on miscarriage and the couple relationship. Even further, a framework for understanding miscarriage is nonexistent. This study aims to explore the phenomenon of miscarriage as well as provide a framework for understanding miscarriage. The current study will look at miscarriage through the lenses of ambiguous loss theory and trauma theory. The sample consisted of 10 females, five who interviewed as individuals and 5 who interviewed with their partners as a couple. Semi-structured, open-ended interviews were conducted with each individual participant, and the five couples were interviewed as a couple as well. From the data, six themes and four subthemes emerged for the female experience: Emotional toll, Stolen dreams, No one understands, He loves me in a different way, Why? I don’t understand, and In the end, I have my faith. -

Handbook for the Judiciary on Effective Criminal Justice

Handbook for the Judiciary on Effective Criminal Justice Responses to Gender-based Violence against Women and Girls Cover photo: ©iStock.com/Berezko UNITED NATIONS OFFICE ON DRUGS AND CRIME Vienna Handbook for the Judiciary on Effective Criminal Justice Responses to Gender-based Violence against Women and Girls UNITED NATIONS Vienna, 2019 © United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2019. All rights reserved. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitations of its frontiers or boundaries. Mention of firm names and com- mercial products does not imply the endorsement of the United Nations. Publishing production: English, Publishing and Library Section, United Nations Office at Vienna. Acknowledgements The Handbook for the Judiciary on Effective Criminal Justice Responses to Gender-based Violence against Women and Girls has been prepared for the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) by Eileen Skinnider, Associate, International Centre for Criminal Law Reform and Criminal Justice Policy. A first draft of the handbook was reviewed and discussed during an expert meeting held in Vienna from 26 to 30 November 2018. UNODC wishes to acknowledge the valuable suggestions and contri- butions of the following experts who participated in that meeting: Ms. Khatia Ardazishvili, Ms. Linda Michele Bradford-Morgan, Ms. Aditi Choudhary, Ms. Teresa Doherty, Ms. Ivana Hrdličková, Ms. Vivian Lopez Nuñez, Ms. Sarra Ines Mechria, Ms. Suntariya Muanpawong, Ms. -

Study on the Effects of New Information Technologies on the Abuse and Exploitation of Children

Study on the Effects of New Information Technologies on the Abuse and Exploitation of Children on the Technologies of New Information Study on the Effects Study on the Effects of New Information Technologies on the Abuse and Exploitation of Children UNITED NATIONS OFFICE ON DRUGS AND CRIME Vienna Study on the Effects of New Information Technologies on the Abuse and Exploitation of Children UNITED NATIONS New York, 2015 © United Nations, May 2015. All rights reserved, worldwide. This report has not been formally edited and remains subject to editorial changes. The contents of this report do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of UNODC or contributory organizations and neither do they imply any endorsement. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Information on uniform resource locators and links to Internet sites contained in the present publication are provided for the convenience of the reader and are correct at the time of issue. The United Nations takes no responsibility for the continued accuracy of that information or for the content of any external website. Publishing production: English, Publishing and Library Section, United Nations Office at Vienna. Acknowledgements This report was prepared pursuant to ECOSOC resolution 2011/33 on Prevention, protection and international cooperation against the use of new information technologies to abuse and/or exploit children by Conference Support Section, Organized Crime Branch, Division for Treaty Affairs, UNODC, under the supervision of John Sandage (former Director, Division for Treaty Affairs), Sara Greenblatt and Loide Lungameni (former and current Chief, Organized Crime Branch, respectively), and Gillian Murray (former Chief, Conference Support Section). -

Compensation and Revenge Emily Sherwin Cornell Law School, [email protected]

Cornell Law Library Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository Cornell Law Faculty Publications Faculty Scholarship 12-2003 Compensation and Revenge Emily Sherwin Cornell Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/facpub Part of the Law and Society Commons, Legal History, Theory and Process Commons, and the Remedies Commons Recommended Citation Sherwin, Emily, "Compensation and Revenge" (2003). Cornell Law Faculty Publications. Paper 833. http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/facpub/833 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cornell Law Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Compensation and Revenge EMILY SHERWIN* TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRO DUCTIO N ................................................................................................. 1387 II. COMPENSATION AND Loss ADJUSTMENT .......................................................... 1389 A . Uncom pensated Loss .............................................................................. 1389 B . L im ited F ocus ......................................................................................... 1390 C. Nonpecuniary Losses .............................................................................. 1392 D. Other Limitations, Including Costs........................................................