Cassette Tape 2.0 Media Plasticity in Underground Music Networks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uila Supported Apps

Uila Supported Applications and Protocols updated Oct 2020 Application/Protocol Name Full Description 01net.com 01net website, a French high-tech news site. 050 plus is a Japanese embedded smartphone application dedicated to 050 plus audio-conferencing. 0zz0.com 0zz0 is an online solution to store, send and share files 10050.net China Railcom group web portal. This protocol plug-in classifies the http traffic to the host 10086.cn. It also 10086.cn classifies the ssl traffic to the Common Name 10086.cn. 104.com Web site dedicated to job research. 1111.com.tw Website dedicated to job research in Taiwan. 114la.com Chinese web portal operated by YLMF Computer Technology Co. Chinese cloud storing system of the 115 website. It is operated by YLMF 115.com Computer Technology Co. 118114.cn Chinese booking and reservation portal. 11st.co.kr Korean shopping website 11st. It is operated by SK Planet Co. 1337x.org Bittorrent tracker search engine 139mail 139mail is a chinese webmail powered by China Mobile. 15min.lt Lithuanian news portal Chinese web portal 163. It is operated by NetEase, a company which 163.com pioneered the development of Internet in China. 17173.com Website distributing Chinese games. 17u.com Chinese online travel booking website. 20 minutes is a free, daily newspaper available in France, Spain and 20minutes Switzerland. This plugin classifies websites. 24h.com.vn Vietnamese news portal 24ora.com Aruban news portal 24sata.hr Croatian news portal 24SevenOffice 24SevenOffice is a web-based Enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems. 24ur.com Slovenian news portal 2ch.net Japanese adult videos web site 2Shared 2shared is an online space for sharing and storage. -

Garage Zine Scionav.Com Vol. 3 Cover Photography: Clayton Hauck

GARAGE ZINE SCIONAV.COM VOL. 3 COVER PHOTOGRAPHY: CLAYTON HAUCK STAFF Scion Project Manager: Jeri Yoshizu, Sciontist Editor: Eric Ducker Creative Direction: Scion Art Director: malbon Production Director: Anton Schlesinger Contributing Editor: David Bevan Assistant Editor: Maud Deitch Graphic Designers: Nicholas Acemoglu, Cameron Charles, Kate Merritt, Gabriella Spartos Sheriff: Stephen Gisondi CONTRIBUTORS Writer: Jeremy CARGILL Photographers: Derek Beals, William Hacker, Jeremy M. Lang, Bryan Sheffield, REBECCA SMEYNE CONTACT For additional information on Scion, email, write or call. Scion Customer Experience 19001 S. Western Avenue Company references, advertisements and/ Mail Stop WC12 or websites listed in this publication are Torrance, CA 90501 not affiliated with Scion, unless otherwise Phone: 866.70.SCION noted through disclosure. Scion does not Fax: 310.381.5932 warrant these companies and is not liable for Email: Email us through the contact page their performances or the content on their located on scion.com advertisements and/or websites. Hours: M-F, 6am-5pm PST Online Chat: M-F, 6am-6pm PST © 2011 Scion, a marque of Toyota Motor Sales U.S.A., Inc. All rights reserved. Scion GARAGE zine is published by malbon Scion and the Scion logo are trademarks of For more information about MALBON, contact Toyota Motor Corporation. [email protected] 00430-ZIN03-GR SCION A/V SCHEDULE JUNE Scion Garage 7”: Cola Freaks/Digital Leather (June 7) Scion Presents: Black Lips North American Tour The Casbah in San Diego, CA (June 9) Velvet Jones -

Tuareg Music and Capitalist Reckonings in Niger a Dissertation Submitted

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Rhythms of Value: Tuareg Music and Capitalist Reckonings in Niger A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnomusicology by Eric James Schmidt 2018 © Copyright by Eric James Schmidt 2018 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Rhythms of Value: Tuareg Music and Capitalist Reckonings in Niger by Eric James Schmidt Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnomusicology University of California, Los Angeles, 2018 Professor Timothy D. Taylor, Chair This dissertation examines how Tuareg people in Niger use music to reckon with their increasing but incomplete entanglement in global neoliberal capitalism. I argue that a variety of social actors—Tuareg musicians, fans, festival organizers, and government officials, as well as music producers from Europe and North America—have come to regard Tuareg music as a resource by which to realize economic, political, and other social ambitions. Such treatment of culture-as-resource is intimately linked to the global expansion of neoliberal capitalism, which has led individual and collective subjects around the world to take on a more entrepreneurial nature by exploiting representations of their identities for a variety of ends. While Tuareg collective identity has strongly been tied to an economy of pastoralism and caravan trade, the contemporary moment demands a reimagining of what it means to be, and to survive as, Tuareg. Since the 1970s, cycles of drought, entrenched poverty, and periodic conflicts have pushed more and more Tuaregs to pursue wage labor in cities across northwestern Africa or to work as trans- ii Saharan smugglers; meanwhile, tourism expanded from the 1980s into one of the region’s biggest industries by drawing on pastoralist skills while capitalizing on strategic essentialisms of Tuareg culture and identity. -

Cisco SCA BB Protocol Reference Guide

Cisco Service Control Application for Broadband Protocol Reference Guide Protocol Pack #60 August 02, 2018 Cisco Systems, Inc. www.cisco.com Cisco has more than 200 offices worldwide. Addresses, phone numbers, and fax numbers are listed on the Cisco website at www.cisco.com/go/offices. THE SPECIFICATIONS AND INFORMATION REGARDING THE PRODUCTS IN THIS MANUAL ARE SUBJECT TO CHANGE WITHOUT NOTICE. ALL STATEMENTS, INFORMATION, AND RECOMMENDATIONS IN THIS MANUAL ARE BELIEVED TO BE ACCURATE BUT ARE PRESENTED WITHOUT WARRANTY OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED. USERS MUST TAKE FULL RESPONSIBILITY FOR THEIR APPLICATION OF ANY PRODUCTS. THE SOFTWARE LICENSE AND LIMITED WARRANTY FOR THE ACCOMPANYING PRODUCT ARE SET FORTH IN THE INFORMATION PACKET THAT SHIPPED WITH THE PRODUCT AND ARE INCORPORATED HEREIN BY THIS REFERENCE. IF YOU ARE UNABLE TO LOCATE THE SOFTWARE LICENSE OR LIMITED WARRANTY, CONTACT YOUR CISCO REPRESENTATIVE FOR A COPY. The Cisco implementation of TCP header compression is an adaptation of a program developed by the University of California, Berkeley (UCB) as part of UCB’s public domain version of the UNIX operating system. All rights reserved. Copyright © 1981, Regents of the University of California. NOTWITHSTANDING ANY OTHER WARRANTY HEREIN, ALL DOCUMENT FILES AND SOFTWARE OF THESE SUPPLIERS ARE PROVIDED “AS IS” WITH ALL FAULTS. CISCO AND THE ABOVE-NAMED SUPPLIERS DISCLAIM ALL WARRANTIES, EXPRESSED OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING, WITHOUT LIMITATION, THOSE OF MERCHANTABILITY, FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE AND NONINFRINGEMENT OR ARISING FROM A COURSE OF DEALING, USAGE, OR TRADE PRACTICE. IN NO EVENT SHALL CISCO OR ITS SUPPLIERS BE LIABLE FOR ANY INDIRECT, SPECIAL, CONSEQUENTIAL, OR INCIDENTAL DAMAGES, INCLUDING, WITHOUT LIMITATION, LOST PROFITS OR LOSS OR DAMAGE TO DATA ARISING OUT OF THE USE OR INABILITY TO USE THIS MANUAL, EVEN IF CISCO OR ITS SUPPLIERS HAVE BEEN ADVISED OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH DAMAGES. -

Razorcake Issue #82 As A

RIP THIS PAGE OUT WHO WE ARE... Razorcake exists because of you. Whether you contributed If you wish to donate through the mail, any content that was printed in this issue, placed an ad, or are a reader: without your involvement, this magazine would not exist. We are a please rip this page out and send it to: community that defi es geographical boundaries or easy answers. Much Razorcake/Gorsky Press, Inc. of what you will fi nd here is open to interpretation, and that’s how we PO Box 42129 like it. Los Angeles, CA 90042 In mainstream culture the bottom line is profi t. In DIY punk the NAME: bottom line is a personal decision. We operate in an economy of favors amongst ethical, life-long enthusiasts. And we’re fucking serious about it. Profi tless and proud. ADDRESS: Th ere’s nothing more laughable than the general public’s perception of punk. Endlessly misrepresented and misunderstood. Exploited and patronized. Let the squares worry about “fi tting in.” We know who we are. Within these pages you’ll fi nd unwavering beliefs rooted in a EMAIL: culture that values growth and exploration over tired predictability. Th ere is a rumbling dissonance reverberating within the inner DONATION walls of our collective skull. Th ank you for contributing to it. AMOUNT: Razorcake/Gorsky Press, Inc., a California not-for-profit corporation, is registered as a charitable organization with the State of California’s COMPUTER STUFF: Secretary of State, and has been granted official tax exempt status (section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code) from the United razorcake.org/donate States IRS. -

EDMTCC 2014 – the EDM Guide

EDMTCC 2014 F# The EDM Guide: Technology, Culture, Curation Written by Robby Towns EDMTCC.COM [email protected] /EDMTCC NESTAMUSIC.COM [email protected] @NESTAMUSIC ROBBY TOWNS AUTHOR/FOUNDER/ENTHUSIAST HANNAH LOVELL DESIGNER LIV BULI EDITOR JUSTINE AVILA RESEARCH ASSISTANT ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS SIMON MORRISON GOOGLE VINCENT REINDERS 22TRACKS GILLES DE SMIT 22TRACKS LUKE HOOD UKF DANA SHAYEGAN THE COLLECTIVE BRIAN LONG KNITTING FACTORY RECORDS ERIC GARLAND LIVE NATION LABS BOB BARBIERE DUBSET MEDIA HOLDINGS GLENN PEOPLES BILLBOARD MEGAN BUERGER BILLBOARD THE RISE OF EDM 4 1.1 SURVIVAL OF THE FITTEST 6 1.2 DISCO TO THE DROP 10 1.3 A REAL LIFE VIDEO GAME 11 1.4 $6.2 BILLION GLOBAL INDUSTRY 11 1.5 GOING PUBLIC 13 1.6 USB 14 TECHNOLOGY: 303, 808, 909 15 2.1 ABLETON LIVE 18 2.2 SERATO 19 2.3 BEATPORT 21 2.4 SOUNDCLOUD 22 2.5 DUBSET MEDIA HOLDINGS 23 CULTURE: BIG BEAT TO MAIN STREET 24 3.1 DUTCH DOMINANCE 26 3.2 RINSE FM 28 3.3 ELECTRIC DAISY CARNIVAL 29 3.4 EDM FANS = HYPERSOCIAL 30 CURATION: DJ = CURATOR 31 4.1 BOOMRAT 33 4.2 UKF 34 4.3 22TRACKS 38 BONUS TRACK 41 THE RISE OF EDM “THE MUSIC HAS SOMETHING IN COMMON WITH THE CURRENT ENGLISH- SYNTHESIZER LED ELECTRONIC DANCE MUSIC...” –LIAM LACEY, CANADIAN GLOBE & MAIL 1982 EDMTCC.COM What is “EDM”? The answer from top brands, and virtually to this question is not the every segment of the entertain- purpose of this paper, but is ment industry is looking to cap- a relevant topic all the same. -

The Menstrual Cramps / Kiss Me, Killer

[email protected] @NightshiftMag NightshiftMag nightshiftmag.co.uk Free every month NIGHTSHIFT Issue 279 October Oxford’s Music Magazine 2018 “What was it like getting Kate Bush’s approval? One of the best moments ever!” photo: Oli Williams CANDYCANDY SAYSSAYS Brexit, babies and Kate Bush with Oxford’s revitalised pop wonderkids Also in this issue: Introducing DOLLY MAVIES Wheatsheaf re-opens; Cellar fights on; Rock Barn closes plus All your Oxford music news, previews and reviews, and seven pages of local gigs for October NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] Online: nightshiftmag.co.uk host a free afternoon of music in the Wheatsheaf’s downstairs bar, starting at 3.30pm with sets from Adam & Elvis, Mark Atherton & Friends, Twizz Twangle, Zim Grady BEANIE TAPES and ALL WILL BE WELL are among the labels and Emma Hunter. releasing new tapes for Cassette Store Day this month. Both locally- The enduring monthly gig night, based labels will have special cassette-only releases available at Truck run by The Mighty Redox’s Sue Store on Saturday 13th October as a series of events takes place in record Smith and Phil Freizinger, along stores around the UK to celebrate the resurgence of the format. with Ainan Addison, began in Beanie Tapes release an EP by local teenage singer-songwriter Max October 1991 with the aim of Blansjaar, titled `Spit It Out’, as well as `Continuous Play’, a compilation recreating the spirit of free festivals of Oxford acts featuring 19 artists, including Candy Says; Gaz Coombes; in Oxford venues and has proudly Lucy Leave; Premium Leisure and Dolly Mavies (pictured). -

Aaron Spectre «Lost Tracks» (Ad Noiseam, 2007) | Reviews На Arrhythmia Sound

2/22/2018 Aaron Spectre «Lost Tracks» (Ad Noiseam, 2007) | Reviews на Arrhythmia Sound Home Content Contacts About Subscribe Gallery Donate Search Interviews Reviews News Podcasts Reports Home » Reviews Aaron Spectre «Lost Tracks» (Ad Noiseam, 2007) Submitted by: Quarck | 19.04.2008 no comment | 198 views Aaron Spectre , also known for the project Drumcorps , reveals before us completely new side of his work. In protovoves frenzy breakgrindcore Specter produces a chic downtempo, idm album. Lost Tracks the result of six years of work, but despite this, the rumor is very fresh and original. The sound is minimalistic without excesses, but at the same time the melodies are very beautiful, the bit powerful and clear, pronounced. Just want to highlight the composition of Break Ya Neck (Remix) , a bit mystical and mysterious, a feeling, like wandering somewhere in the http://www.arrhythmiasound.com/en/review/aaron-spectre-lost-tracks-ad-noiseam-2007.html 1/3 2/22/2018 Aaron Spectre «Lost Tracks» (Ad Noiseam, 2007) | Reviews на Arrhythmia Sound dusk. There was a place and a vocal, in a track Degrees the gentle voice Kazumi (Pink Lilies) sounds. As a result, Lost Tracks can be safely put on a par with the works of such mastadonts as Lusine, Murcof, Hecq. Tags: downtempo, idm Subscribe Email TOP-2013 Submit TOP-2014 TOP-2015 Tags abstract acid ambient ambient-techno artcore best2012 best2013 best2014 best2015 best2016 best2017 breakcore breaks cyberpunk dark ambient downtempo dreampop drone drum&bass dub dubstep dubtechno electro electronic experimental female vocal future garage glitch hip hop idm indie indietronica industrial jazzy krautrock live modern classical noir oldschool post-rock shoegaze space techno tribal trip hop Latest The best in 2017 - albums, places 1-33 12/30/2017 The best in 2017 - albums, places 66-34 12/28/2017 The best in 2017. -

Drone Music from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Drone music From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Drone music Stylistic origins Indian classical music Experimental music[1] Minimalist music[2] 1960s experimental rock[3] Typical instruments Electronic musical instruments,guitars, string instruments, electronic postproduction equipment Mainstream popularity Low, mainly in ambient, metaland electronic music fanbases Fusion genres Drone metal (alias Drone doom) Drone music is a minimalist musical style[2] that emphasizes the use of sustained or repeated sounds, notes, or tone-clusters – called drones. It is typically characterized by lengthy audio programs with relatively slight harmonic variations throughout each piece compared to other musics. La Monte Young, one of its 1960s originators, defined it in 2000 as "the sustained tone branch of minimalism".[4] Drone music[5][6] is also known as drone-based music,[7] drone ambient[8] or ambient drone,[9] dronescape[10] or the modern alias dronology,[11] and often simply as drone. Explorers of drone music since the 1960s have included Theater of Eternal Music (aka The Dream Syndicate: La Monte Young, Marian Zazeela, Tony Conrad, Angus Maclise, John Cale, et al.), Charlemagne Palestine, Eliane Radigue, Philip Glass, Kraftwerk, Klaus Schulze, Tangerine Dream, Sonic Youth,Band of Susans, The Velvet Underground, Robert Fripp & Brian Eno, Steven Wilson, Phill Niblock, Michael Waller, David First, Kyle Bobby Dunn, Robert Rich, Steve Roach, Earth, Rhys Chatham, Coil, If Thousands, John Cage, Labradford, Lawrence Chandler, Stars of the Lid, Lattice, -

Popular Music and Society Artists As Entrepreneurs, Fans As Workers

This article was downloaded by: [James Madison University] On: 03 November 2014, At: 16:54 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Popular Music and Society Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rpms20 Artists as Entrepreneurs, Fans as Workers Jeremy Wade Morris Published online: 15 May 2013. To cite this article: Jeremy Wade Morris (2014) Artists as Entrepreneurs, Fans as Workers, Popular Music and Society, 37:3, 273-290, DOI: 10.1080/03007766.2013.778534 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03007766.2013.778534 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content. This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. -

Complete Band and Panel Listings Inside!

THE STROKES FOUR TET NEW MUSIC REPORT ESSENTIAL October 15, 2001 www.cmj.com DILATED PEOPLES LE TIGRE CMJ MUSIC MARATHON ’01 OFFICIALGUIDE FEATURING PERFORMANCES BY: Bis•Clem Snide•Clinic•Firewater•Girls Against Boys•Jonathan Richman•Karl Denson•Karsh Kale•L.A. Symphony•Laura Cantrell•Mink Lungs• Murder City Devils•Peaches•Rustic Overtones•X-ecutioners and hundreds more! GUEST SPEAKER: Billy Martin (Medeski Martin And Wood) COMPLETE D PANEL PANELISTS INCLUDE: BAND AN Lee Ranaldo/Sonic Youth•Gigi•DJ EvilDee/Beatminerz• GS INSIDE! DJ Zeph•Rebecca Rankin/VH-1•Scott Hardkiss/God Within LISTIN ININ STORESSTORES TUESDAY,TUESDAY, SEPTEMBERSEPTEMBER 4.4. SYSTEM OF A DOWN AND SLIPKNOT CO-HEADLINING “THE PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE TOUR” BEGINNING SEPTEMBER 14, 2001 SEE WEBSITE FOR DETAILS CONTACT: STEVE THEO COLUMBIA RECORDS 212-833-7329 [email protected] PRODUCED BY RICK RUBIN AND DARON MALAKIAN CO-PRODUCED BY SERJ TANKIAN MANAGEMENT: VELVET HAMMER MANAGEMENT, DAVID BENVENISTE "COLUMBIA" AND W REG. U.S. PAT. & TM. OFF. MARCA REGISTRADA./Ꭿ 2001 SONY MUSIC ENTERTAINMENT INC./ Ꭿ 2001 THE AMERICAN RECORDING COMPANY, LLC. WWW.SYSTEMOFADOWN.COM 10/15/2001 Issue 735 • Vol 69 • No 5 CMJ MUSIC MARATHON 2001 39 Festival Guide Thousands of music professionals, artists and fans converge on New York City every year for CMJ Music Marathon to celebrate today's music and chart its future. In addition to keynote speaker Billy Martin and an exhibition area with a live performance stage, the event features dozens of panels covering topics affecting all corners of the music industry. Here’s our complete guide to all the convention’s featured events, including College Day, listings of panels by 24 topic, day and nighttime performances, guest speakers, exhibitors, Filmfest screenings, hotel and subway maps, venue listings, band descriptions — everything you need to make the most of your time in the Big Apple. -

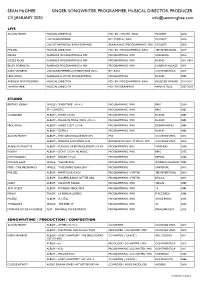

CV JANUARY 2020 [email protected]

SEAN McGHEE SINGER, SONGWRITER, PROGRAMMER, MUSICAL DIRECTOR, PRODUCER. CV JANUARY 2020 [email protected] LIVE ALISON MOYET MUSICAL DIRECTOR MD / BV / SYNTHS / BASS MODEST! 2018- LIVE BAND MEMBER BV / SYNTHS / BASS MODEST! 2013- LIVE SET ARRANGER & PROGRAMMER ARRANGING / PROGRAMMING / MIX MODEST! 2013- PHILDEL MUSICAL DIRECTOR MD / BV / PROGRAMMING / BASS YEE INVENTIONS 2019 KIESZA PLAYBACK PROGRAMMING & MIX PROGRAMMING / MIX UNIVERSAL 2014 RIZZLE KICKS PLAYBACK PROGRAMMING & MIX PROGRAMMING / MIX ISLAND 2011-2014 BLUEY ROBINSON PLAYBACK PROGRAMMING & MIX PROGRAMMING / MIX LONDON VILLAGE 2013 KATE HAVNEVIK LIVE BAND MEMBER (CHINESE TOUR 2015) BV / BASS CONTINENTICA 2015 FROU FROU PLAYBACK & SYNTH PROGRAMMING PROGRAMMING ISLAND 2003 ANDREW MONTGOMERY MUSICAL DIRECTOR MD / BV / PROGRAMMING / BASS RULED BY DREAMS 2014-2015 TEMPOSHARK MUSICAL DIRECTOR MD / PROGRAMMING PAPER & GLUE 2007-2010 STUDIO BRITNEY SPEARS SINGLE – “EVERYTIME” (UK #1) PROGRAMMING / MIX BMG 2004 EP – CHAOTIC PROGRAMMING / MIX BMG 2005 SUGABABES ALBUM – THREE (UK #3) PROGRAMMING / MIX ISLAND 2003 ALBUM – TALLER IN MORE WAYS (UK #1) PROGRAMMING / MIX ISLAND 2005 FROU FROU ALBUM – SHREK 2 OST (US #8) PROGRAMMING / MIX DREAMWORKS 2004 ALBUM – DETAILS PROGRAMMING / MIX ISLAND 2002 ALISON MOYET ALBUM – THE TURN: DELUXE EDITION MIX COOKING VINYL 2015 ALBUM – MINUTES & SECONDS LIVE BACKING VOCALS / SYNTHS / MIX COOKING VINYL 2014 ALANIS MORISSETTE ALBUM – FLAVORS OF ENTANGLEMENT (US #8) PROGRAMMING / BVs WARNERS 2008 ROBYN ALBUM – DON’T STOP THE MUSIC PROGRAMMING / MIX BMG