Lizzie Fisher Kurt Schwitters and the Lake District

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Additions to CASCAT from Carlisle Archives

Cumbria Archive Service CATALOGUE: new additions August 2021 Carlisle Archive Centre The list below comprises additions to CASCAT from Carlisle Archives from 1 January - 31 July 2021. Ref_No Title Description Date BRA British Records Association Nicholas Whitfield of Alston Moor, yeoman to Ranald Whitfield the son and heir of John Conveyance of messuage and Whitfield of Standerholm, Alston BRA/1/2/1 tenement at Clargill, Alston 7 Feb 1579 Moor, gent. Consideration £21 for Moor a messuage and tenement at Clargill currently in the holding of Thomas Archer Thomas Archer of Alston Moor, yeoman to Nicholas Whitfield of Clargill, Alston Moor, consideration £36 13s 4d for a 20 June BRA/1/2/2 Conveyance of a lease messuage and tenement at 1580 Clargill, rent 10s, which Thomas Archer lately had of the grant of Cuthbert Baynbrigg by a deed dated 22 May 1556 Ranold Whitfield son and heir of John Whitfield of Ranaldholme, Cumberland to William Moore of Heshewell, Northumberland, yeoman. Recites obligation Conveyance of messuage and between John Whitfield and one 16 June BRA/1/2/3 tenement at Clargill, customary William Whitfield of the City of 1587 rent 10s Durham, draper unto the said William Moore dated 13 Feb 1579 for his messuage and tenement, yearly rent 10s at Clargill late in the occupation of Nicholas Whitfield Thomas Moore of Clargill, Alston Moor, yeoman to Thomas Stevenson and John Stevenson of Corby Gates, yeoman. Recites Feb 1578 Nicholas Whitfield of Alston Conveyance of messuage and BRA/1/2/4 Moor, yeoman bargained and sold 1 Jun 1616 tenement at Clargill to Raynold Whitfield son of John Whitfield of Randelholme, gent. -

Complete 230 Fellranger Tick List A

THE LAKE DISTRICT FELLS – PAGE 1 A-F CICERONE Fell name Height Volume Date completed Fell name Height Volume Date completed Allen Crags 784m/2572ft Borrowdale Brock Crags 561m/1841ft Mardale and the Far East Angletarn Pikes 567m/1860ft Mardale and the Far East Broom Fell 511m/1676ft Keswick and the North Ard Crags 581m/1906ft Buttermere Buckbarrow (Corney Fell) 549m/1801ft Coniston Armboth Fell 479m/1572ft Borrowdale Buckbarrow (Wast Water) 430m/1411ft Wasdale Arnison Crag 434m/1424ft Patterdale Calf Crag 537m/1762ft Langdale Arthur’s Pike 533m/1749ft Mardale and the Far East Carl Side 746m/2448ft Keswick and the North Bakestall 673m/2208ft Keswick and the North Carrock Fell 662m/2172ft Keswick and the North Bannerdale Crags 683m/2241ft Keswick and the North Castle Crag 290m/951ft Borrowdale Barf 468m/1535ft Keswick and the North Catbells 451m/1480ft Borrowdale Barrow 456m/1496ft Buttermere Catstycam 890m/2920ft Patterdale Base Brown 646m/2119ft Borrowdale Caudale Moor 764m/2507ft Mardale and the Far East Beda Fell 509m/1670ft Mardale and the Far East Causey Pike 637m/2090ft Buttermere Bell Crags 558m/1831ft Borrowdale Caw 529m/1736ft Coniston Binsey 447m/1467ft Keswick and the North Caw Fell 697m/2287ft Wasdale Birkhouse Moor 718m/2356ft Patterdale Clough Head 726m/2386ft Patterdale Birks 622m/2241ft Patterdale Cold Pike 701m/2300ft Langdale Black Combe 600m/1969ft Coniston Coniston Old Man 803m/2635ft Coniston Black Fell 323m/1060ft Coniston Crag Fell 523m/1716ft Wasdale Blake Fell 573m/1880ft Buttermere Crag Hill 839m/2753ft Buttermere -

Patterdale & Glenridding War Memorial Book of Remembrance

Patterdale & Glenridding War Memorial Book of Remembrance World War One World War Two www.ullswatermemorial.co.uk www.patterdaletoday.co.uk/history www.cwgc.org 2 Table of Contents Introduction ..……………………………………. 4 Memorial Names ……………………………….. 5 Details on First World War Names……….. 6 – 24 Details on Second World War Names ….. 25 – 33 Glenridding Public Hall Roll of Honour… 34 Memorial History ……………………………….. 35 Further Information ……………………………. 36 They shall grow not old, as we that are left grow old: Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn. At the going down of the sun and in the morning, We will remember them www.ullswatermemorial.co.uk www.patterdaletoday.co.uk/history www.cwgc.org 3 Patterdale & Glenridding War Memorial Project Towards the end of the First World War the inhabitants of Patterdale collected money in order to establish a permanent Monument as a Memorial to the Officers and Men who fell in the Great War. William Hibbert Marshall, owner of Patterdale Hall, donated a piece of land to allow for the building of a permanent Monument in February 1921 on the shores of Ullswater, midway between Glenridding and Patterdale. The memorial slab was hewn from a twenty ton piece of local slate and the eventual undressed slate stone still weighs in at around 5 tons. It was unveiled in October 1921. As part of the 100th Anniversary Commemoration of the outbreak of World War One, we have tried to find out more about the men whose names are inscribed on the Memorial, from both World Wars, on the Roll of Honour in the Village Hall, and also about life in and around Patterdale and Glenridding at the time. -

The Westmorland Way

THE WESTMORLAND WAY WALKING IN THE HEART OF THE LAKES THE WESTMORLAND WAY - SELF GUIDED WALKING HOLIDAY SUMMARY The Westmorland Way is an outstanding walk from the Pennines, through the heart of the Lake District and to the Cumbrian Coast visiting the scenic and historical highlights of the old county of Westmorland. Your walk begins in Appleby-in-Westmorland which lies in the sandstone hills of the Pennines. It then heads west into the Lake District National Park, where you spend five unforgettable days walking through the heart of the Lake District. A final day of walking brings you to Arnside on Morecambe Bay. Along the way you will enjoy some of the Lake District’s most delightful landscapes, villages and paths. Ullswater, Windermere, Elterwater, Grasmere, Patterdale, Askham, Great Asby and Troutbeck all feature on your route through the lakes. Exploring the old county of Westmorland’s unparalleled variety is what makes this walk so enjoyable. From lakeside walks to mountain paths and canal towpaths the seven sections of the Westmorland Way Tour: The Westmorland Way will keep you enthralled from beginning to end. Code: WESWW1 Our walking holidays on the Westmorland Way include hand-picked overnight accommodation in high Type: Self-Guided Walking Holiday quality B&B’s, country inns, and guesthouses. Each is unique and offers the highest levels of welcome, Price: See Website atmosphere and outstanding local cuisine. We also include daily door to door baggage transfers, a Single Supplement: See Website Dates: April - October guidebook, detailed maps and a comprehensive pre-departure information pack as well as emergency Walking Days: 7 support, should you need it. -

Glenridding Common

COMMONMEMBERS’ NEWSGROUND A JOHN MUIR TRUST PUBLICATION SUMMER 2019 Welcome to Glenridding Common In late autumn 2017, following consultation with local and I was taken on as Property Manager following a 23-year role as national stakeholders, we were delighted when the Lake District area ranger with the National Park Authority, while the National Park Authority confirmed that the John Muir Trust employment of Isaac Johnston from Bowness, funded by Ala would take over the management of Glenridding Common, Green, has enabled a young person to gain a full-time position at initially on a three-year lease. the very start of his conservation and land management career. For those unfamiliar with our work, the John Muir Trust is a As you will read in the pages that follow, we have been UK-wide conservation charity dedicated to the experience, extremely busy over the past 18 months. Our work has included protection and repair of wild places. We manage wild land, vital footpath maintenance and repair – again utilising the skills of inspire people of all ages and backgrounds to discover wildness two local footpath workers – the enhancement of England’s most through our John Muir Award initiative, valuable collection of Arctic-alpine and campaign to conserve our plants (generously aided by the Lake wildest places. District Foundation), litter collection To be entrusted with managing and tree planting. Glenridding Common – the first time We have also carried out extensive that the Trust has been directly survey work to establish base-line involved in managing land outside information for a variety of species on this Scotland – is a responsibility that we nationally important upland site. -

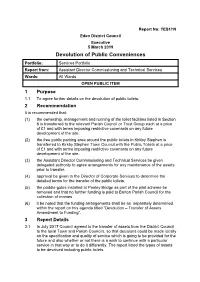

Devolution of Public Conveniences

Report No: TES1/19 Eden District Council Executive 5 March 2019 Devolution of Public Conveniences Portfolio: Services Portfolio Report from: Assistant Director Commissioning and Technical Services Wards: All Wards OPEN PUBLIC ITEM 1 Purpose 1.1 To agree further details on the devolution of public toilets. 2 Recommendation It is recommended that: (1) the ownership, management and running of the toilet facilities listed in Section 6 is transferred to the relevant Parish Council or Trust Group each at a price of £1 and with terms imposing restrictive covenants on any future development of the site. (2) the free public parking area around the public toilets in Kirkby Stephen is transferred to Kirkby Stephen Town Council with the Public Toilets at a price of £1 and with terms imposing restrictive covenants on any future development of the site. (3) the Assistant Director Commissioning and Technical Services be given delegated authority to agree arrangements for any maintenance of the assets prior to transfer. (4) approval be given to the Director of Corporate Services to determine the detailed terms for the transfer of the public toilets. (5) the paddle gates installed at Pooley Bridge as part of the pilot scheme be removed and that no further funding is paid to Barton Parish Council for the collection of monies (6) it be noted that the funding arrangements shall be as separately determined within the report on this agenda titled “Devolution – Transfer of Assets Amendment to Funding”. 3 Report Details 3.1 In July 2017 Council agreed to the transfer of assets from the District Council to the local Town and Parish Councils, so that decisions could be made locally on the specification and quality of service which is going to be provided for the future and also whether or not there is a wish to continue with a particular service in that way or to do it differently. -

South Lakeland

South Lakeland Changes to Monday to Friday Changes to Saturday Changes to Sunday Windermere - Bowness-on- Windermere - Newby Bridge - 6 Timetable unchanged + - - Haverthwaite - Ulverston - Dalton - Barrow Croftlands - Ulverston - Dalton - Hourly (half hourly service Barrow - 6 + $ Hospital - Barrow Ulverston with X6) Oxenholme - Helme Chase - Asda - 41/41B : Suspended + - - 41 / 41A Kendal Parks - Westmorland Hospital 41A : Hourly : 0715 to 1815 + - - Rinkfield - Helme Chase - Heron Hill - 42 : Suspended + - - 42 Valley Drive - Castle Green 42A : Hourly 0738 to 1738 + - - 43 : Hourly 0748 to 1748 + - - 43 43A Morrisons - Sandylands 43A : Suspended + - - 44 Beast Banks - Hallgarth Hourly 0710 to 1710 + - - 45 Burneside - Kentrigg Timetable unchanged + - - Beast Banks - Vicarage Park - 46 Timetable unchanged + - - Wattsfield - Collinfield - Kirkbarrow 81 Kirkby Lonsdale - Hornby - Lancaster Timetable unchanged + - - Arnside - Kendal - Queen Elizabeth 99 Suspended until schools fully re-open - - School (Kirkby Lonsdale) (termtime) Kendal - Grayrigg - Tebay - Orton - 106 Timetable unchanged - - Shap - Lowther - Clifton - Penrith Brough - Kirkby Stephen - Sedbergh - 502 Suspended until College fully re-open - - Kendal (College Days) Kendal - Windermere - Ambleside - Will continue to run to Winter 505 + $ Hawkshead - Coniston timetable Appleby - Penrith - Shap - Tebay - 506 Suspended until College fully re-open - - Kendal (College Days) Will continue to run to Winter Penrith - Pooley Bridge - Aira Force - + $ 508 timetable Patterdale (Ullswater) -

Tour of the Lake District

Walking Holidays in Britain’s most Beautiful Landscapes Tour of the Lake District The Tour of the Lake District is a 93 mile circular walk starting and finishing in the popular tourist town of Windermere. This trail takes in each of the main Lake District valleys, along lake shores and over remote mountain passes. You will follow in the footsteps of shepherds and drovers along ancient pathways from one valley to the next. Starting in Windermere, the route takes you through the picturesque towns of Ambleside, Coniston, Keswick and Grasmere (site of Dove Cottage the former home of the romantic poet William Wordsworth). The route takes you through some of the Lake District’s most impressive valleys including the more remote valleys of the western Lake District such as Eskdale, Wasdale and Ennerdale, linked together with paths over high mountain passes. One of the many highlights of this scenic tour is a visit to the remote Wasdale Head in the shadow of Scafell Pike, the highest mountain in England. Mickledore - Walking Holidays to Remember 1166 1 Walking Holidays in Britain’s most Beautiful Landscapes Summary the path, while still well defined, becomes rougher farm, which is open to the public and offers a great Why do this walk? on higher ground. insight into 17th Century Lakeland life. Further • Stay in the popular tourist towns of Keswick, along the viewpoint at Jenkin Crag is worth a Ambleside, Grasmere, and Coniston. Signposting: There are no official route waymarks short detour before continuing to the bustling • Walk along the shores of Wastwater, Buttermere and you will need to use your route description and town of Ambleside. -

PATTERDALE HALL MULTI ACTIVITY WEEK Age 8 to 12 and Age 13 to 15 4 Nights Break - 31St August to 4Th September 2020 BOOKING FORM ATTACHED

PATTERDALE HALL MULTI ACTIVITY WEEK Age 8 to 12 and Age 13 to 15 4 nights break - 31st August to 4th September 2020 BOOKING FORM ATTACHED What’s on offer: Full board, 4 nights en–suite dormitory accommodation at Patterdale Hall, close to the shores of Ullswater in the Lake District National Park Aim of the break is to have fun, build confidence and broaden your horizons 3 1/2 days of activities including archery, low ropes course, gorge walking, hill walking and stand up paddle boarding Evening entertainment including lawn games, an astronomy evening, bush craft and campfire Highly experienced instructor team used to working with and getting the best out of individuals On site pastoral care Games room including table tennis and snooker, as well as grounds to explore and kick a ball around. Tea, coffee, hot chocolate and cordials available at all times £400.00 per person Further details and a sample programme can be found on our web site www.patterdalehall.org.uk Please find our booking form on the next page. If you have any queries at all please contact us on [email protected] or call The Hall on 017684 82233 Page 1 of 4 PATTERDALE HALL MULTI ACTIVITY WEEK 4 nights break - 31st August to 4th September 2020 BOOKING FORM & TERMS & CONDITIONS Parent /Guardian Full Name: _______________________________________________________________ Contact Address:_________________________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________________________________ -

The Heart of Lakeland

TOUR 21 The Heart of Lakeland Leave the soft red sandstones of Carlisle and the Eden Valley to weave through hills of volcanic rocks and lakes carved out during the last Ice Age, before heading into the Pennines, with their different, gentler beauty. ITINERARY CARLISLE Ǡ Caldbeck (13m-21km) GRASMERE Ǡ Ambleside (4m-6.5km) CALDBECK Ǡ Bassenthwaite AMBLESIDE Ǡ Coniston (7m-11km) (9m-14.5km) CONISTON Ǡ Bowness (10m-16km) BASSENTHWAITE Ǡ Buttermere BOWNESS Ǡ Patterdale (13m-21km) (20m-32km) PATTERDALE Ǡ Penrith (14m-23km) BUTTERMERE Ǡ Keswick (13m-21km) PENRITH Ǡ Haltwhistle (34m-55km) KESWICK Ǡ Grasmere (15m-24km) HALTWHISTLE Ǡ Carlisle (23m-37km) 2 DAYS ¼ 175 MILES ¼ 282KM GLASGOW Birdoswald hing Irt Hadrian's ENGLAND B6318 Wall HOUSESTEADS A6 A69 A 07 Greenhead 7 1 4 9 Haltwhistle Ede A6 n Brampton 11 A 9 6 A6 8 9 CARLISLE Jct 43 Knarsdale 5 9 9 9 Eden 5 2 A Slaggyford S A 5 6 A Tyne B 6 8 Dalston 9 South Tynedale A689 Railway B Alston 53 Welton Pe 05 t te r i B l 52 M 99 6 Caldbeck Eden Ostrich A Uldale 1 World Melmerby 59 6 1 A w 8 6 6 A B5291 2 lde Ca Langwathby Cockermouth Bassenthwaite Penrith A Bassenthwaite 10 A A6 66 6 Lake 6 6 931m Wh A A66 inla 5 Skiddaw Pas tte 91 M Brougham Castle Low s r 2 6 66 9 A 2 5 6 2 Lorton A A B5292 3 4 5 Aira B B 5 Force L 2 Keswick o 8 Derwent Ullswater w 9 t Crummock Water e h l e Water a Glenridding r Buttermere d Thirlmere w o Patterdale 3 r 950m Buttermere r o Helvellyn 9 B Honister A 5 Pass 9 Rydal Kirkstone 1 5 Mount Pass Haweswater A Grasmere 5 9 2 Ambleside Stagshaw 6 Lake District National 3 59 Park Visitor Centre A Hawkshead Windermere Coniston 85 B52 8 7 0 10 miles Bowness-on-Windermere Near Sawrey 0 16 km Coniston Windermere 114 Water _ Carlisle Visitor Centre, Old Town Leave Bassenthwaite on Crummock Water, Buttermere Hall, Green Market, Carlisle unclassified roads towards the B5291 round the northern E Keswick, Cumbria Take the B5299 south from shores of the lake, then take The capital of the northern Lake Carlisle to Caldbeck. -

Kendal Archive Centre

Cumbria Archive Service CATALOGUE: new additions August 2021 Kendal Archive Centre The list below comprises additions to CASCAT from Kendal Archives from 1 January - 31 July 2021. Ref_No Title Description Date 1986- LDSPB/1/13 Minute book 1989 1989- LDSPB/1/14 Minute book 1993 1993- LDSPB/1/15 Minute book 1997 1996- LDSPB/1/16 Minute book 2001 Oct 2001- LDSPB/1/17 Minutes Dec 2001 Jan 2002- LDSPB/1/18 Minutes Mar 2002 Apr 2002- LDSPB/1/19 Minutes Jun 2002 Jul 2002- LDSPB/1/20 Minutes Sep 2002 Sep 2002- LDSPB/1/21 Minutes Dec 2002 Dec 2002- LDSPB/1/22 Minutes Mar 2003 Mar LDSPB/1/23 Minutes 2003-Jun 2003 Jun 2003- LDSPB/1/24 Minutes Sep 2003 Sep 2003- LDSPB/1/25 Minutes Dec 2003 Dec 2003- LDSPB/1/26 Minutes Mar 2004 Mar LDSPB/1/27 Minutes 2004-Jun 2004 Jun 2004- LDSPB/1/28 Minutes Sep 2004 Sep 2004- LDSPB/1/29 Minutes Dec 2004 Mar LDSPB/1/30 Minutes 2005-Jun 2005 Jun 2005- LDSPB/1/31 Minutes Sep 2005 Sep 2005- LDSPB/1/32 Minutes Dec 2005 Including newspaper cuttings relating to 1985- LDSPB/12/1/1 Thirlmere reservoir, papers relating to water levels, 1998 and Thirlmere Plan First Review 1989. Leaflets and newspaper cuttings relating to 1989- LDSPB/12/1/2 Mountain safety safety on the fells and winter walking. 1990s Tourism and conservation Papers relating to funding conservation 2002- LDSPB/12/1/3 partnership through tourism. 2003 Includes bibliography of useful books; newspaper articles on Swallows and Amazons, John Ruskin, Wordsworth, 1988- LDSPB/12/1/4 Literary Alfred Wainwright, Beatrix Potter; scripts 2003 of audio/visual presentations regarding literary tours of Lake District. -

Westmoreland in the Late Seventeenth Century by Colin Phillips

WESTMORLAND ABOUT 1670 BY COLIN PHILLIPS Topography and climate This volume prints four documents relating to the hearth tax in Westmorland1. It is important to set these documents in their geographical context. Westmorland, until 1974 was one of England’s ancient counties when it became part of Cumbria. The boundaries are shown on map 1.2 Celia Fiennes’s view in 1698 of ‘…Rich land in the bottoms, as one may call them considering the vast hills above them on all sides…’ was more positive than that of Daniel Defoe who, in 1724, considered Westmorland ‘A country eminent only for being the wildest, most barren and frightful of any that I have passed over in England, or even Wales it self. ’ It was a county of stark topographical contrasts, fringed by long and deep waters of the Lake District, bisected by mountains with high and wild fells. Communications were difficult: Helvellyn, Harter Fell, Shap Fell and the Langdale Fells prevented easy cross-county movement, although there were in the seventeenth century three routes identified with Kirkstone, Shap, and Grayrigg.3 Yet there were more fertile lowland areas and 1 TNA, Exchequer, lay subsidy rolls, E179/195/73, compiled for the Michaelmas 1670 collection, and including Kendal borough. The document was printed as extracts in W. Farrer, Records relating to the barony of Kendale, ed. J. F. Curwen (CWAAS, Record Series, 4 & 5 1923, 1924; reprinted 1998, 1999); and, without the exempt, in The later records relating to north Westmorland, ed. J. F. Curwen (CWAAS, Record Series, 8, 1932); WD/Ry, box 28, Ms R, pp.1-112, for Westmorland, dated 1674/5, and excluding Kendal borough and Kirkland (heavily edited in J.