Ideals and Practices of Rationality – an Interview with Lorraine Daston Michael Trevor Bycroft *

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Philosophy of Social Science

Philosophy of Social Science Philosophy of Social Science A New Introduction Edited by Nancy Cartwright and Eleonora Montuschi 1 1 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP, United Kingdom Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries © The several contributors 2014 The moral rights of the authors have been asserted First Edition published in 2014 Impression: 1 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Control Number: 2014938929 ISBN 978–0–19–964509–1 (hbk.) ISBN 978–0–19–964510–7 (pbk.) Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. -

CURRICULUM VITAE January, 2018 DANIEL GARBER

CURRICULUM VITAE January, 2018 DANIEL GARBER Position: A. Watson Armour III University Professor of Philosophy Address: Department of Philosophy 1879 Hall Princeton University Princeton, NJ 08544-1006 Address (September 2017-July 2018) Institut d’études avancées 17, quai d’Anjou 75004 Paris France Telephone: 609-258-4307 (voice) 609-258-1502 (FAX) 609-258-4289 (Departmental office) Email: [email protected] Erdös number: 16 EDUCATIONAL RECORD Harvard University, 1967-1975 A.B. in Philosophy, 197l A.M. in Philosophy, 1974 Ph.D. in Philosophy, 1975 TEACHING EXPERIENCE Princeton University 2002- Professor of Philosophy and Associated Faculty, Program in the History of Science 2005-12 Chair, Department of Philosophy 2008-09 Old Dominion Professor 2009- Associated Faculty, Department of Politics 2009-16 Stuart Professor of Philosophy Garber -2- 2016- A. Watson Armour III University Professor of Philosophy University of Chicago 1995-2002 Lawrence Kimpton Distinguished Service Professor in Philosophy, the Committee on Conceptual and Historical Studies of Science, the Morris Fishbein Center for Study of History of Science and Medicine and the College 1986-2002 Professor 1982-86 Associate Professor (with tenure) 1975-82 Assistant Professor 1998-2002 Chairman, Committee on Conceptual and Historical Studies of Science (formerly Conceptual Foundations of Science) 2001 Acting Chairman, Department of Philosophy 1995-98 Associate Provost for Education and Research 1994-95 Chairman, Conceptual Foundations of Science 1987-94 Chairman, Department of Philosophy Harvard College 1972-75 Teaching Assistant and Tutor University of Minnesota, Spring 1979, Visiting Assistant Professor of Philosophy Johns Hopkins University, 1980-1981, Visiting Assistant Professor of Philosophy Princeton University 1982-1983 Visiting Associate Professor of Philosophy Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton, 1985-1986, Member École Normale Supérieure (Lettres) (Lyon, France), November 2000, Professeur invitée. -

Reason and Representation in Scientific Simulation

Reason and Representation in Scientific Simulation Matthew Spencer | PhD Thesis Centre for Cultural Studies, Goldsmiths, University of London Declaration The work presented in this thesis is the candidate's own. - 2 - Abstract This thesis is a study of scientific practice in computational physics. It is based on an 18 month period of ethnographic research at the Imperial College Applied Modelling and Computation Group. Using a theoretical framework drawn from practice theory, science studies, and historical epistemology, I study how simulations are developed and used in science. Emphasising modelling as a process, I explore how software provides a distinctive kind of material for doing science on computers and how images and writings of various kinds are folded into the research process. Through concrete examples the thesis charts how projects are devised and evolve and how they draw together materials and technologies into semi-stable configurations that crystallise around the objects of their concern, what Hans-Jorg Rheinberger dubbed “epistemic things”. The main pivot of the research, however, is the connection of practice-theoretical science studies with the philosophy of Gaston Bachelard, whose concept of “phenomenotechnique” facilitates a rationalist reading of scientific practice. Rather than treating reason as a singular logic or method, or as a faculty of the mind, Bachelard points us towards processes of change within actual scientific research, a dynamic reason immanent to processes of skilled engagement. Combining this study of reason with the more recent attention to things within research from materialist and semiotic traditions, I also revive a new sense for the term “representation”, tracing the multiple relationships and shifting identities and differences that are involved in representing. -

The Unity of Science in Early-Modern Philosophy: Subalternation, Metaphysics and the Geometrical Manner in Scholasticism, Galileo and Descartes

The Unity of Science in Early-Modern Philosophy: Subalternation, Metaphysics and the Geometrical Manner in Scholasticism, Galileo and Descartes by Zvi Biener M.A. in Philosophy, University of Pittsburgh, 2004 B.A. in Physics, Rutgers University, 1995 B.A. in Philosophy, Rutgers University, 1995 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2008 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH FACULTY OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Zvi Biener It was defended on April 3, 2008 and approved by Peter Machamer J.E. McGuire Daniel Garber James G. Lennox Paolo Palmieri Dissertation Advisors: Peter Machamer, J.E. McGuire ii Copyright c by Zvi Biener 2008 iii The Unity of Science in Early-Modern Philosophy: Subalternation, Metaphysics and the Geometrical Manner in Scholasticism, Galileo and Descartes Zvi Biener, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2008 The project of constructing a complete system of knowledge—a system capable of integrating all that is and could possibly be known—was common to many early-modern philosophers and was championed with particular alacrity by Ren´eDescartes. The inspiration for this project often came from mathematics in general and from geometry in particular: Just as propositions were ordered in a geometrical demonstration, the argument went, so should propositions be ordered in an overall system of knowledge. Science, it was thought, had to proceed more geometrico. I offer a new interpretation of ‘science more geometrico’ based on an analysis of the explanatory forms used in certain branches of geometry. These branches were optics, as- tronomy, and mechanics; the so-called subalternate, subordinate, or mixed-mathematical sciences. -

Let's Not Talk About Objectivity

Chapter 2 Let’s Not Talk About Objectivity Ian Hacking The first landmark event in twenty-first-century thinking about objectivity was, as is well known, Lorraine Daston and Peter Galison’s Objectivity (2007). It is a magisterial historical study of an epistemological concept, namely “objectivity”. Hence I call it a contribution to what I call (if it wants a name) meta-epistemology, although other prefer the less apt but better sounding historical epistemology. You will find more food for thought, not to mention headaches, in their book, than in any other body of work about objectivity. It will seem that Objectivity rejects the injunction stated in my title, for what is the book about, but objectivity? The authors are talking about objectivity if anyone is! Analytic philosopherslike myself make what others regard as too many distinctions, and I shall illustrate that here. Objectivity is about the concept of objectivity, its past uses, and the practices associated with it. For me, a concept is a word in its sites (Hacking 1984). In this context, that means the sites in which words cognate with “objective” were used over the past three centuries, the practices within which they were deployed, who had authority when using them, the actual modes of inscription, which in this case is closely associated with the use of pictures and other types of images. For me, as for a builder, a site is a rich field of activity to be described from many points of view, almost innumerable perspectives. Objectivity is a triumph of that type of analysis; it is not talking about objectivity but about the concept of objectivity (a distinction we most clearly owe to Gottlob Frege writing about number). -

Fetishizing Science

International Conference Fetishizing Science Views of science differ widely even among relatively similar cultures – just consider the many differences between Humanities and Geisteswissenschaften. But since the early 20th century, there has been general agreement about the priority of the natural sciences – in truth-value, in independence from ideology, and in funding. At the same time, the rise of the history of science as a discipline has cast doubt on most of the myths that make natural science a priority. Recent studies have called into question hard distinctions between reason and nature, while enriching our notions of objectivity, observation, and rationality itself. Leading historians of science, as well as other historians, philosophers and critics will discuss the extent to which the imperialism of the natural sciences can be justified. Einstein Forum Am Neuen Markt 7 14467 Potsdam Tel.: 0331 271 78 0 Fax: 0331 271 78 27 http://www.einsteinforum.de [email protected] Speakers and Themes Lorraine Daston, Berlin When Science Went Modern – and Why Starting circa 1920, commentators on the modern condition – philosophers like Alfred North Whitehead and Edmund Husserl, sociologists like Max Weber and Georg Simmel, and historians like E.A. Burtt and Herbert Butterfield – link modernity with science, more specifically with the Scientific Revolution. It was not any specific discovery of theory or even science-based technology that had wrought this transformation; it was the creation of the "modern mind". Triumphal versions of this narrative celebrated it as the prime mover of the Enlightenment and progress; tragic versions mourned the loss of the cozy medieval cosmos and an enchanted world. -

The Two Cultures” and the Historical Perspective on Science As a Culture Francesca Rochberg, Professor of History, University of California, Riverside

Forum on Public Policy “The Two Cultures” and the Historical Perspective on Science as a Culture Francesca Rochberg, Professor of History, University of California, Riverside Abstract In the Rede lecture of 1959, C.P.Snow speaks in terms of two cultures, one of science, the other of literary intellectuals. Snow’s discussion presupposes that science represents a culture of its own, independent of and superior to the arts and humanities, and unified within itself. At our present distance from this claim, Snow’s point of view can be seen as a product of the philosophical orientation to science as an embodiment of universal truths about nature as well as cold war pressures on the West to improve educational standards in science. As the terms in which science is discussed have changed in the last nearly half-century, so has our response to the terms of Snow’s “Two Cultures”altered with time. The fields of history and sociology of science have shown the degree to which science is both fully enmeshed in society and conditioned by history, making it more difficult to support the idea of a separate “culture” of science immune from the effects of society and history. That the viability of a culture of science as an independent entity is contested in contemporary academic circles furthermore affects the mode in which students of science and the humanities are inculcated. This paper discusses the historical perspective on science as a culture and considers the impact of changing views about the nature, aims, and methods of science on the teaching of science and its history. -

Let's Not Talk About Objectivity

Chapter 2 Let’s Not Talk About Objectivity Ian Hacking The first landmark event in twenty-first-century thinking about objectivity was, as is well known, Lorraine Daston and Peter Galison’s Objectivity (2007). It is a magisterial historical study of an epistemological concept, namely “objectivity”. Hence I call it a contribution to what I call (if it wants a name) meta-epistemology, although other prefer the less apt but better sounding historical epistemology. You will find more food for thought, not to mention headaches, in their book, than in any other body of work about objectivity. It will seem that Objectivity rejects the injunction stated in my title, for what is the book about, but objectivity? The authors are talking about objectivity if anyone is! Analytic philosophers like myself make what others regard as too many distinctions, and I shall illustrate that here. Objectivity is about the concept of objectivity, its past uses, and the practices associated with it. For me, a concept is a word in its sites (Hacking 1984). In this context, that means the sites in which words cognate with “objective” were used over the past three centuries, the practices within which they were deployed, who had authority when using them, the actual modes of inscription, which in this case is closely associated with the use of pictures and other types of images. For me, as for a builder, a site is a rich field of activity to be described from many points of view, almost innumerable perspectives. Objectivity is a triumph of that type of analysis; it is not talking about objectivity but about the concept of objectivity (a distinction we most clearly owe to Gottlob Frege writing about number). -

The Scientist As Philosopher

The Scientist as Philosopher 3 Berlin Heidelberg New York Hong Kong London Milan Paris Tokyo Friedel Weinert The Scientist as Philosopher Philosophical Consequences of Great Scientific Discoveries With 52 Figures 13 Dr. Friedel Weinert University of Bradford Department of Social Sciences and Humanities Bradford BD7 1DP Great Britain e-mail: [email protected] CoverfiguresreproducedfromFaraday,M.:ACourseof6LecturesontheVariousForcesofMatter and Their Relation to Each Other. Ed. by W. Crookes (Griffin, London, Glasgow 1860) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data. Weinert, Friedel, 1950– . The scientist as philosopher: philosophical consequences of great scientific discoveries Friedel Weinert. p.cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 3-540-20580-2 (acid-free paper) 1. Discoveries in science. 2. Science–Philosophy. 3. Philosophy and science. I. Title Q180.55.D57W45 2004 501–dc22 2003064922 ISBN 3-540-21374-0 Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg New York This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broad- casting, reproduction on microfilm or in any other way, and storage in data banks. Duplication of this publication or parts thereof is permitted only under the provisions of the German Copyright Law of September 9, 1965, in its current version, and permission for use must always be obtained from Springer-Verlag. Violations are liable for prosecution under the German Copyright Law. Springer-Verlag is a part of Springer Science+Business Media springeronline.com © Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2005 Printed in Germany The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, etc. -

Table of Contents

Vol. 47, No. 3 July 2018 Newsof the lHistoryetter of Science Society Table of Contents HSS Announces HSS Announces New Society Editors New Society Editors 1 Three Historians of Science Share the Dan David Prize of [At its recent meetings, the HSS Executive Committee One Million Dollars for Their and the HSS Council voted overwhelmingly to accept Contributions to Humanity 5 the Committee on Publications recommendation that the See You In Seattle 6 Society appoint Alexandra (Alix) Hui and Matthew (Matt) Lavine as Co-Editors for the Society (July 2019 to June Member News 7 2024). We invited Alix and Matt to share their vision for In Memoriam 13 Isis and the Society’s various publications.] HSS News 15 In July of 2019, the Editorship of the History of Science News from the Profession 20 Society will move from its present home at the Descartes the development of our forays into social media and Centre in Utrecht to the Starkville campus of Mississippi online content. Floris’s many contributions to our State University. As the incoming Editors, we (Alix Hui discipline as a scholar and editor defy easy synthesis and Matt Lavine) are excited for the opportunity to help or brief recitation, but as we write this (barely a week shape the Society’s publications, in what we hope will be after receiving word of our selection) we are already a close collaboration with its members. To that end, we’d keenly aware of the enormous debt that we owe him like to use this opportunity to share with our colleagues for the order and efficiency that he has brought to the our ideas and aspirations for our coming five-year term, editorship. -

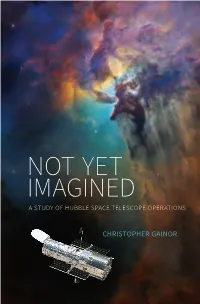

Not Yet Imagined: a Study of Hubble Space Telescope Operations

NOT YET IMAGINED A STUDY OF HUBBLE SPACE TELESCOPE OPERATIONS CHRISTOPHER GAINOR NOT YET IMAGINED NOT YET IMAGINED A STUDY OF HUBBLE SPACE TELESCOPE OPERATIONS CHRISTOPHER GAINOR National Aeronautics and Space Administration Office of Communications NASA History Division Washington, DC 20546 NASA SP-2020-4237 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Gainor, Christopher, author. | United States. NASA History Program Office, publisher. Title: Not Yet Imagined : A study of Hubble Space Telescope Operations / Christopher Gainor. Description: Washington, DC: National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Office of Communications, NASA History Division, [2020] | Series: NASA history series ; sp-2020-4237 | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Summary: “Dr. Christopher Gainor’s Not Yet Imagined documents the history of NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope (HST) from launch in 1990 through 2020. This is considered a follow-on book to Robert W. Smith’s The Space Telescope: A Study of NASA, Science, Technology, and Politics, which recorded the development history of HST. Dr. Gainor’s book will be suitable for a general audience, while also being scholarly. Highly visible interactions among the general public, astronomers, engineers, govern- ment officials, and members of Congress about HST’s servicing missions by Space Shuttle crews is a central theme of this history book. Beyond the glare of public attention, the evolution of HST becoming a model of supranational cooperation amongst scientists is a second central theme. Third, the decision-making behind the changes in Hubble’s instrument packages on servicing missions is chronicled, along with HST’s contributions to our knowledge about our solar system, our galaxy, and our universe. -

Nancy Cartwright's Philosophy of Science

Nancy Cartwright’s Philosophy of Science T&F Proofs: Not for Distribution Routledge Studies in the Philosophy of Science SERIE S EDITOR , Editor’s School 1. Cognition, Evolution and Rationality A Cognitive Science for the Twenty- First Century Edited by António Zilhão 2. Conceptual Systems Harold I. Brown 3. Nancy Cartwright’s Philosophy of Science Edited by Stephan Hartmann, Carl Hoefer and Luc Bovens T&F Proofs: Not for Distribution Nancy Cartwright’s Philosophy of Science Edited by Stephan Hartmann, Carl Hoefer and Luc Bovens New York London T&F Proofs: Not for Distribution First published 2008 by Routledge 270 Madison Ave, New York, NY 10016 Simultaneously published in the UK by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2008. “To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of thousands of eBooks please go to www.eBookstore.tandf.co.uk.” © 2008 Stephan Hartmann, Carl Hoefer and Luc Bovens All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereaf- ter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. Trademark Notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trade- marks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Cartwright, Nancy.