Common Garter Snake

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bull Snake Class: Reptilia

Pituophis catenifer sayi Bull Snake Class: Reptilia. Order: Squamata. Family: Colubridae. Other names: Gopher Snake, Pine Snake Physical Description: Bull snakes are usually yellow in color, with brown, black or reddish colored blotching or saddle spots on the sides of the snake. There are dark spots placed between the blotches or saddle spots. Below this is a further row of smaller dark spots. The belly is light brown. Many variations in color have been found, including albinos and white variations. This snake has a small head and a large nose shield, which it uses to dig. They often exceed 6 feet in length, with specimens of up to 100 inches being recorded. Males are generally larger then females. The bull snake is a member of the family of harmless snakes, or Colubridae. This is the largest order of snakes, representing two-thirds of all known snake species. Members of this family are found on all continents except Antarctica, widespread from the Arctic Circle to the southern tips of South America and Africa. All but a handful of species are harmless snakes, not having venom or the ability to deliver toxic saliva through fangs. Most harmless snakes subdue their prey through constriction, striking and seizing small rodents, birds or amphibians and quickly wrapping their body around the prey causing suffocation. While other small species such as the common garter snake lack powers to constrict and feed on only small prey it can overpower. Diet in the Wild: Bull snakes eat small mammals, such as mice, rats, large bugs as well as ground nesting birds, lizards and the young of other snakes. -

Guide to the Reptil and Am Hibians of Central Minnesota- Regi N3w

This document is made available electronically by the Minnesota Legislative Reference Library as part of an ongoing digital archiving project. http://www.leg.state.mn.us/lrl/lrl.asp (Funding for document digitization was provided, in part, by a grant from the Minnesota Historical & Cultural Heritage Program.) Guide to the Reptil and Am hibians of Central Minnesota- Regi n3W Minnesota Department of Natural Resources January 1, 1979 Guide to the Herpetofauna of Central Minnesota Region 3 - West This preliminary guide has been prepared as a reference to the occurrence and distribution of reptiles and amphibians of Region 3 - West in Central Minnesota. Taxonomy and identification are based on "A Field Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians" by Roger Conant (Second Edition 1975). Figure 1 is a map of the region. Counties Included: Benton, Cass, Crow Wing, Morrison, Sherburne, Stearns, Todd, Wadena and Wright. SPECIES LIST Turtles Salamanders Common snapping turtle Blue-spotted salamander Map turtle Eastern tiger salamander Western painted turtle Mudpuppy (?) *Blanding's turtle *Central (Common) newt (?) Western spiny softshell *Red-backed salamander (?) Lizards Toads Northern priaire skink American toad Snakes Frogs Red-bellied snake Northern spring peeper Texas brown (DeKay's) snake Common (gray) treefrog Northern water snake Boreal chorus frog J s.s. Western plains garter snake Western chorus frog Red-sided garter snake] s.s. Mink frog Eastern garter snake Northern leopard frog Eastern hognose snake Green frog *Western smooth green snake} s.s. Wood frog *Eastern smooth green snake Bull snake s.s. - single species (?) - hypothetical species - reports needed * - special interest species - reports needed Summary A total of 24 species are found in Region 3 - West. -

Mather Field Vernal Pools Garter Snakes

Mather Field Vernal Pools common name Garter Snakes Thamnophis sirtalis sirtalis scientific (Common Garter Snake) names Thamnophis elegans elegans (Western Terrestrial Garter Snake) phylum Chordata class Reptilia order Squamata family Colubridae habitat vernal pool grasslands and many other habitats, often near water size 0.46 to 1.3 meters © Ken Davis description The Common (or Valley) Garter Snake is easily identifiable by a black body, yellow stripes down the back, and red blotches on the sides. The Western Terrestrial Garter Snake has a black or dark gray back with a dull yellow stripe down the middle. The dark background color has tiny white spots, which can be hard to see. fun facts When handled or otherwise disturbed, Garter Snakes usually release a stinky- smelling musk. life cycle During the winter, Garter Snakes hibernate under rocks and rotting logs, and in rodent burrows. They select mates in the spring after they come out of hibernation. In July, seven to thirty young are born live. ecology Garter Snakes feed on many different animals, including fish, frogs, toads, salamanders, insects, and earthworms. They are excellent swimmers and are usually found close to some source of water. They are eaten by a variety of mammals, birds and other snakes. conservation Some people kill snakes because they are afraid that the snakes might hurt them. They do not realize that the snakes are even more afraid of humans than we are of them! Garter Snakes, like many snakes, play an important role in controlling populations of rodents. Rodents are a group of mammals that includes mice, pocket gophers, voles, ground squirrels and other species. -

Garter Snake Article Marin IJ David Herlocker If You Spend Any Amount

Garter Snake Article Marin IJ David Herlocker If you spend any amount of time on the trails of Marin County, chances are that you occasionally catch a glimpse of a snake. It is not uncommon to find a gopher snake sitting motionless in a fire road, or to see the last few inches of a sleek brown racer as it disappears into the trailside grass. If your travels take you near a lake, a stream, or any other freshwater habitat, chances are you will encounter one of the three species of garter snakes that live here. The coastal marshes of Point Reyes are where you will usually find the gaudy red and turquoise common garter snake (our showy subspecies is called the California red-sided garter snake). In coyote brush and meadows you can expect to see our version of the western terrestrial garter snake (which is called the coast garter snake), and along our perennial streams and lakeshores you are most likely to encounter an aquatic garter snake. All of these snakes are characterized by the presence of one or more pale stripes that run the length of their body. When you see a garter snake against a plain background, this pattern looks anything but camouflaged, but when found among grasses or floating stems at the edge of a pond, the color scheme allows the snake to blend in perfectly. The name “garter snake” comes from this color pattern’s resemblance to the old fashioned striped garters that were used to hold men’s sleeves in place. Many people mistakenly refer to them as ‘garden snakes”; although they may be found in gardens, there is actually no species called the garden snake. -

References for Life History

Literature Cited Adler, K. 1979. A brief history of herpetology in North America before 1900. Soc. Study Amphib. Rept., Herpetol. Cir. 8:1-40. 1989. Herpetologists of the past. In K. Adler (ed.). Contributions to the History of Herpetology, pp. 5-141. Soc. Study Amphib. Rept., Contrib. Herpetol. no. 5. Agassiz, L. 1857. Contributions to the Natural History of the United States of America. 2 Vols. Little, Brown and Co., Boston. 452 pp. Albers, P. H., L. Sileo, and B. M. Mulhern. 1986. Effects of environmental contaminants on snapping turtles of a tidal wetland. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol, 15:39-49. Aldridge, R. D. 1992. Oviductal anatomy and seasonal sperm storage in the southeastern crowned snake (Tantilla coronata). Copeia 1992:1103-1106. Aldridge, R. D., J. J. Greenshaw, and M. V. Plummer. 1990. The male reproductive cycle of the rough green snake (Opheodrys aestivus). Amphibia-Reptilia 11:165-172. Aldridge, R. D., and R. D. Semlitsch. 1992a. Female reproductive biology of the southeastern crowned snake (Tantilla coronata). Amphibia-Reptilia 13:209-218. 1992b. Male reproductive biology of the southeastern crowned snake (Tantilla coronata). Amphibia-Reptilia 13:219-225. Alexander, M. M. 1943. Food habits of the snapping turtle in Connecticut. J. Wildl. Manag. 7:278-282. Allard, H. A. 1945. A color variant of the eastern worm snake. Copeia 1945:42. 1948. The eastern box turtle and its behavior. J. Tenn. Acad. Sci. 23:307-321. Allen, W. H. 1988. Biocultural restoration of a tropical forest. Bioscience 38:156-161. Anonymous. 1961. Albinism in southeastern snakes. Virginia Herpetol. Soc. Bull. -

Snakes of Berryessa

SNAKES OF BERRYESSA Introduction There are around 2700 Berryessa region, the Gopher Snake , yellow belly. Head snake species in the western rattlesnake, Pituophis roughly as thick as the world today. Of these, which is distinctly melanolancus: neck. The tail blunt like 110 species are different in Common. Up to the head. A live birthing indigenous to the United appearance from any 250 cm in length. constrictor. Nocturnal States. Here at Lake of our non-venomous Tan to cream dorsal during the summer. Berryessa, park visitors species. color with brown Found in coniferous have the opportunity to and black markings. forests under rocks and observe as many as Rattlesnakes pose no Dark line in front of logs, usually near a 10 different species serious threat to and behind the permanent source of of snakes. humans. The truth is, eyes. Diurnal water. Feeds on small in the entire United except for the mammals and lizards. Western Yellow Bellied Racer When observing snakes States only 10-12 California Kingsnake hottest portions of Gopher Snake in the wild, it's important Aquatic Garter Snake people die each year summer. Egg laying Western Yellow-Bellied Racer , Coluber constrictor : to follow certain due to snake bites, with 99% of these deaths attributed species that is found in almost any habitat. Can be Common. Up to 175 cm in length. guidelines. The fallen trees, stands of brush, and rock to either the western or eastern diamondback arboreal. Feeds on birds, lizards, rodents and eggs. Brown to olive skin with a pale yellow belly. Young piles found around Berryessa serve as homes, hunting rattlesnake, neither of which are found in the Berryessa Hisses loudly and vibrates it's tail when disturbed. -

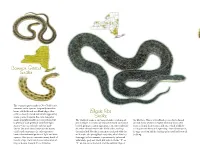

Snakes of New York State

Common Garter Snake ˜e common garter snake is New York’s most common snake species, frequently found in lawns, old ÿelds and woodland edges. One Black Rat of three closely related and similar appearing snake species found in the state, the garter Snake snake is highly variable in color pattern, but ˜e black rat snake is our longest snake, reaching six the blotches. ˜is is a woodland species, but is found is generally dark greenish with three light feet in length. Its scales are uniformly black and faintly around barns where it is highly desirable for its abil- stripes—one on each side and one mid- keeled, giving it a satiny appearance. In some individu- ity to seek and destroy mice and rats, which it kills by dorsal. ˜e mid-dorsal stripe can be barely als, white shows between the black scales, making coiling around them and squeezing. Around farmyards, visible and sometimes the sides appear to the snake look blotchy. Sometimes confused with the its eggs are o˛en laid in shavings piles used for livestock have a checkerboard pattern of light and dark milk snake, the young black rat snake, which hatches bedding. squares. ˜is species consumes many kinds of from eggs in late summer, is prominently patterned insects, slugs, worms and an occasional small with white, grey and black, but lacks both the “Y” or frog or mouse. Length: 16 to 30 inches. “V” on the top of the head, and the reddish tinge to Timber Rattlesnake Copperhead ˜e copperhead is an attractively-patterned, venomous snake with a pinkish-tan color super- imposed on darker brown to chestnut colored saddles that are narrow at the spine and wide at the sides. -

T Exas A& M Natural Resources Institute

Natural Resources Support at Joint Base Species Management McGuire-Dix-Lakehurst (U.S. Air Force) Bog Turtle (PTFL180413) and Pine Snake, Corn Snake, Timber Rattlesnake Species Management (PTFL18NR04) Annual Report David W. Schneider, Robert T. Zappalorti, David Burkett, December 2019 Ryan Fitzgerald, Wade A. Ryberg, Mathew Kramm and Roel R. Lopez Texas A&M Natural Resources Institute Distribution authorized to U.S. Government Agencies only. Species Management ii Natural Resources Support at Joint Base McGuire-Dix-Lakehurst (U.S. Air Force) Bog Turtle (PTFL180413) and Pine Snake, Corn Snake, Timber Rattlesnake Species Management (PTFL18NR04) Annual Report David W. Schneider, Robert T. Zappalorti, David Burkett and Ryan Fitzgerald Herpetological Associates, Inc. 405 Magnolia Road Pemberton, NJ 08068 Phone: 732-833-8600 Wade A. Ryberg, Mathew Kramm and Roel R. Lopez Texas A&M University Natural Resources Institute 578 John Kimbrough Blvd. 2260 TAMU College Station, TX 77840-2260 Phone: 979-845-1851 Annual Report Distribution authorized to U.S. Government Agencies only. Species Management iii Table of Contents Executive Summary…………………………………………………….iv Contact Information……………………………………………………..v Introduction……………………………………………………………….1 Materials and Methods………………………………………………….5 Results of the Invesitigation………………………………………….10 Summary…………………………………………………………………71 Literature Cited………………………………………………………….73 Species Management iv Executive Summary This report describes 2018-19 survey results for bog turtles, northern pine snakes, corn snakes, and timber rattlesnakes on Joint Base McGuire-Dix-Lakehurst (U.S. Air Force; JB MDL). Where appropriate, captured snakes were monitored using telemetry methods over their entire activity season to characterize summer habitat use, determine their home range size, and to locate critical winter den sites. Below we summarize the major findings of this species management project. -

Development and Assessment of a Wildlife Habitat Relationship Model for Terrestrial Vertebrates in the State of Maryland

DEVELOPMENT AND ASSESSMENT OF A WILDLIFE HABITAT RELATIONSHIP MODEL FOR TERRESTRIAL VERTEBRATES IN THE STATE OF MARYLAND by Robert John Northrop A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the University of Delaware in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Wildlife Ecology Spring 2009 Copyright 2009 Robert John Northrop All Rights Reserved DEVELOPMENT AND ASSESSMENT OF A WILDLIFE HABITAT RELATIONSHIP MODEL FOR TERRESTRIAL VERTEBRATES IN THE STATE OF MARYLAND by Robert John Northrop Approved: __________________________________________________________ Jacob L. Bowman, Ph.D. Professor in charge of thesis on behalf of the Advisory Committee Approved: __________________________________________________________ Douglas W. Tallamy, Ph.D. Chair of the Department of Entomology and Wildlife Ecology Approved: __________________________________________________________ Robin Morgan, Ph.D. Dean of the College of Agriculture and Natural Resources Approved: __________________________________________________________ Debra Hess Norris, M.S. Vice Provost for Graduate and Professional Education ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I thank Dr. Jacob Bowman for his patience and continuing support over the past several years. Thanks to Dr. Roland Roth who originally asked me to teach at the University of Delaware in 1989. The experience of teaching wildlife conservation and management at the University for 14 years has changed the way I approach my professional life as a forest ecologist. I also offer a big thank – you to all my students at the University I have learned more from you than you can imagine. I am grateful to the U.S. Forest Service, Dr. Mark Twery and Scott Thomasma, for funding the initial literature review and research, and for ongoing database support as we use this work to build a useful conservation tool for planners and natural resource managers in Maryland. -

St. Vrain State Park

Camping, Fishing, ReptileReptile and and Amphibian Reptiles Birding...Enjoy it all at Reptiles St. Vrain! IdentificationIdentification Guide Guide Camping, Fishing, Reptile and Amphibian Birding...Enjoy it all at Reptiles St. Vrain! This brochureIdentification is meant toGuide be used as ST. VRAIN STATE PARK a guide for identifying the different Reptiles & This brochure is meant to be used as reptile and amphibian species one Amphibians of a guide for identifying the different ReptilesReptiles & Amphibians & might find here at St. Vrain State St. Vrain State Park reptile and amphibian species one IdentificationAmphibians of St. Vrain Guide of Park. St. Vrain State Park might find here at St. Vrain State PleasePark. be respectful of wildlife and IdentificationIdentification Guide Guide give them their space. Do not feed, Please be respectful of wildlife and handle or harass these animals in give them their space. Do not feed, Common Garter Snake any way. handle or harass these animals in Thamnophis sirtalis Common Garter Snake Viewany way.them with caution and respect, and any encounter is sure to be a Thamnophis sirtalis View them with caution and respect, memorable experience for all and any encounter is sure to be a involved. memorable experience for all Asinvolved. always, have fun and be safe! As always, have fun and be safe! Western Terrestrial Garter Snake Thamnophis elegans Western Terrestrial Garter Snake Thamnophis elegans ST. VRAIN STATE PARK St. Vrain State Park 3525 Highway 119 Camping, Fishing, Birding ... Firestone,St. Vrain COState 80504 Park 3525 Highway 119 Enjoy it all at St. Vrain! Phone:Firestone, 303-678-9402 CO 80504 St. -

Garter Snakes by Linda Novak

Notable Natives Garter Snakes by Linda Novak Many people are, at the least, mildly apprehensive when they come across a snake, but the common garter snake Thamnophis sirtalis is a good creature to have around and is likely to be heading away from you when you see it. Garter snakes eat insects, bird eggs, small birds, fish, amphibians and (here’s the beneficial part) field mice and voles. They, in turn, serve as food for bull frogs, hawks, owls, foxes and other predators. Garter snake. Image courtesy of Wikipedia Commons. The most common snake in Illinois, the garter snake is dark brown or black with one to three yellow stripes running from head to tail. The Chicago type, T. s. semifasciatus, has some red on the body, and its side stripes become dashed lines How does one avoid the unfortunate lawnmower-snake near the head. The Chicago garter snake is found mainly in encounter? Garter snakes like to be warm, so they hang out on northeastern Illinois. rocks, mulch and lawns – anywhere there is sun. Before you mow, try to scare them off by scuffling your feet through the Adults can grow to more than three feet long and live for three grass in sunny areas, and then be vigilant. to ten years if they are lucky enough to avoid a lawnmower or car. They spend the winter in hibernacula, holes in the ground Here are some interesting facts about garter snakes and snakes below the frost line. Tolerant of cold weather, garter snakes in general: may emerge on warm winter days to bask in the sun and then return to hibernation when temperatures fall. -

Thamnophis Sirtalis) Stomach Contents Detects Cryptic Range of a Secretive Salamander (Ensatina Eschscholtzii Oregonensis)

Herpetological Conservation and Biology 5(3):395–402. Submitted: 28 July 2010; Accepted: 12 October 2010. PHYLOGENETIC ANALYSIS OF COMMON GARTER SNAKE (THAMNOPHIS SIRTALIS) STOMACH CONTENTS DETECTS CRYPTIC RANGE OF A SECRETIVE SALAMANDER (ENSATINA ESCHSCHOLTZII OREGONENSIS) 1,3 1,4 2 1,5 SEAN B. REILLY , ANDREW D. GOTTSCHO , JUSTIN M. GARWOOD , AND W. BRYAN JENNINGS 1Department of Biological Sciences, Humboldt State University, 1 Harpst St., Arcata, California 95521, USA 2Redwood Sciences Laboratory, Pacific Southwest Research Station, USDA Forest Service, 1700 Bayview Drive, Arcata, California 95521, USA 3Present Address: Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, 3101 Valley Life Sciences Building, University of California, Berkeley, California 94704, USA, email: [email protected] 4Present Address: Department of Biology, San Diego State University, 5500 Campanile Drive, San Diego, California 92182, USA 5Present Address: Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Museu Nacional, Departamento de Vertebrados, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, 20940-040, Brazil Abstract. Given the current global amphibian decline, it is crucial to obtain accurate and current information regarding species distributions. Secretive amphibians such as plethodontid salamanders can be difficult to detect in many cases, especially in remote, high elevation areas. We used molecular phylogenetic analyses to identify three partially digested salamanders palped from the stomachs of three Common Garter Snakes (Thamnophis sirtalis) from the Klamath Mountains in northern California. Our results conclusively show that the salamanders were all individuals of Ensatina eschscholtzii oregonensis, revealing a substantial vertical range extension for this sub-species, and documenting the first terrestrial breeding salamander living in the sub-alpine zone of the Klamath Mountains. Key Words. Common Garter Snake, distribution, Ensatina, Ensatina eschscholtzii, Klamath Mountains, mitochondrial DNA, Thamnophis sirtalis INTRODUCTION breeders.