NZMJ 1473.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

12 October 2009

Organisations referenced in this week’s Field Notes include: ABARES Hell’s Pizza ACT Horizons Regional Council Adelaide Bank Immigration New Zealand Affco Talley Independent Climate Change Committee Alliance Group Internet of Things Apeel Sciences Just Salad Arla Foods Kraft Heinz ASP Kroger Asure Quality Ministry for Primary Industries BakerAg NZ Nestle Bell Flavours and Fragrances New Culture Bellamy Organic Food Group New Zealand Meatworkers Union Bendigo Overseas Investment Office Beyond Meat Paessler Caprine Innovations NZ (CAPRINZ) PepsiCo Carlsberg Pinterest China Mengnui Company Primary ITO Chipotle Provenance Commerce Commission Redefine Meat Community and Public Health RethinkX CPT Capital Sea Shepherd Craigmore Sustainables Shand Thomson Crisp Silberhorn Dairy Goat Co-operative Strong Roots DairyNZ Synlait Danish Crown Taranaki Mounga Department of Conservation Taratahi Agricultural Training Centre Federated Farmers Tastewise Forest and Bird The Economist Magazine Foundation for Arable Research The NZ Institute of Economic Development Future Market Insights The PHW Group Future Thinking Tomra Goode Partners Too Good to Go Grant Thomson Unilever Greenpeace United Nations Groceryshop Whanganui Conservation Department Hanaco Ventures Yaraam Herd Services This week’s headlines: Aquaculture US seafood ban plan causes stir in NZ [13 September/Stuff NZ] Agribusiness New Zealand's primary sector exports reach a record $46.4 billion [16 September/Stuff NZ] Horticulture FAR testing future food crops [17 September/Farmers Weekly] Dairy Goat industry leads world-first research [16 September/Farmers Weekly Kroger expands its line of Apeel produce to tackle food waste [18 International September/Grocery Dive] © 2018 KPMG, a New Zealand partnership and a member firm of the KPMG network of independent member firms affiliated with KPMG International Cooperative (KPMG International), a Swiss entity. -

Food Frontier 2020 State of the Industry

2020 State of the Industry Australia’s Plant-Based Meat Sector Bonus Chapter Cellular Agriculture EXECUTIVE SUMMARY — In a year closing a few months into arguably A growing global call for protein manufacturing revenue and jobs. Products on grocery shelves the most consequential economic disruption diversification doubled to more than 200, 42 percent of which are from in recent history – the global pandemic – one Australian companies. Industry manufacturing is focused in NSW, with an estimated 68 percent of economic emerging industry held strong. Rising interest in alternative proteins – domestically and contribution, followed by Victoria with 28 percent. abroad – comes amidst increasing demand for meat from This report tells the story of Australia’s our growing and increasingly prosperous global population.1 It should be noted that the timeframe for DAE’s data plant-based meat sector over FY20. It’s a story Relying solely on current meat production systems, two underpinning this report (FY20) does not include major of a young industry on an upward trajectory, planets’ worth of resources would be needed to meet the developments in the Australian market across the latter half achieving impressive growth in the face of world’s projected demand for meat by 2050.2 of 2020, from new products on grocery shelves to large new unprecedented adversity. production facilities to export launches. With 22 companies To solve this challenge, environmental, economic and comprising Australia’s plant-based meat industry as of New economic modelling by Deloitte Access Economics (DAE) health authorities worldwide have called for a more December 2020, up from 11 since our previous report for FY19, on Australia’s still emerging plant-based meat sector reveals diverse, sustainable and safe protein supply (read more the industry continues its strong growth today. -

A Cross-Sectional Analysis of the Nutritional Quality of Popular Online Food Delivery Outlets in Australia and New Zealand

nutrients Article Junk Food on Demand: A Cross-Sectional Analysis of the Nutritional Quality of Popular Online Food Delivery Outlets in Australia and New Zealand 1,2, , 3, 4 4 Stephanie R. Partridge * y , Alice A. Gibson y , Rajshri Roy , Jessica A. Malloy , Rebecca Raeside 1, Si Si Jia 1, Anna C. Singleton 1 , Mariam Mandoh 1 , Allyson R. Todd 1, Tian Wang 1, Nicole K. Halim 1, Karice Hyun 1,5 and Julie Redfern 1,6 1 Westmead Applied Research Centre, Faculty of Medicine and Health, The University of Sydney, Sydney 2145, Australia; [email protected] (R.R.); [email protected] (S.S.J.); [email protected] (A.C.S.); [email protected] (M.M.); [email protected] (A.R.T.); [email protected] (T.W.); [email protected] (N.K.H.); [email protected] (K.H.); [email protected] (J.R.) 2 Prevention Research Collaboration, Charles Perkins Centre, Sydney School of Public Health, The University of Sydney, Sydney 2006, Australia 3 Menzies Centre for Health Policy, Sydney School of Public Health, Faculty of Medicine and Health, The University of Sydney, Sydney 2006, Australia; [email protected] 4 Discipline of Nutrition and Dietetics, Faculty of Medical and Health Sciences, The University of Auckland, Auckland 1011, New Zealand; [email protected] (R.R.); [email protected] (J.A.M.) 5 ANZAC Research Institute, Concord Repatriation General Hospital, The University of Sydney, Sydney 2137, Australia 6 The George Institute for Global Health, The University of New South Wales, Camperdown 2006, Australia * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +61-2-8890-8187 These authors contributed equally to this work. -

How Unite Took on Fast Food Companies Over

HOWHOW UNITEUNITE TOOKTOOK ONON FASTFAST FOODFOOD COMPANIESCOMPANIES OVEROVER ZEROZERO HOURHOUR CONTRACTSCONTRACTS (AND(AND WON)WON) by Mike TreenTreen 1 2 Workers in the fast food industry in New Zealand scored a spectacular victory over what has been dubbed “zero hour contracts” during a collective agreement bargaining round over the course of March and April 2015. The campaign played out over the national media as well as on picket lines. The victory was seen by many observers as the product of a determined fight by a valiant group of workers and their union, Unite. It was a morale boost for all working people after what has seemed like a period of retreat for working class struggle in recent years. Unite Union’s National Director Mike Treen tells the inside story of how a union took on the fast food companies and won. Workers in the fast food industry have long identified “zero These zero-hour contracts are not a new phenomenon. hour contracts” as the central problem they face. These They became entrenched in the 1990s during the dark are contracts that don’t guarantee any hours per week, days of the Employment Contracts Act. They affect literally meanwhile workers are expected to work any shifts rostered hundreds of thousands of workers in fast food, cinemas, within the workers “availability”. Managers have power to hotels, home care, security, cleaning, hospitality, restaurants use and abuse the rostering system to reward and punish, and retail. without any real means of holding them to account. The fast food industry in New Zealand includes the foreign This year, all the collective agreements with the major owned McDonald’s, Burger King and Domino’s Pizza chains, fast food companies (McDonald’s, Burger King, Restaurant the locally-owned businesses that pay for the right to market Brands) expired on March 31. -

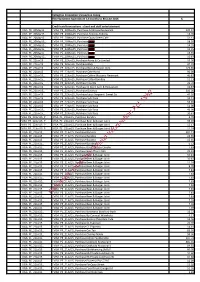

Callaghan Innovation 2015/16 Expenses

Callaghan Innovation transaction listing Entertainment expenditure 12 months to 30 June 2016 $ Credit card transactions - client and staff entertainment VISA PE_20May15_ VISA PE_20May15_Purchase Ambrosia Restaurant 109.57 VISA PE_20May15_ VISA PE_20May15_Purchase Andrew Andrew 14.78 VISA PE_20May15_ VISA PE_20May15_Purchase Quay Street Cafe 51.13 VISA PE_20May15_ VISA PE_20May15_Purchase s9(2)(a) 58.50 VISA PE_20May15_ VISA PE_20May15_Purchase s9(2)(a) 14.35 VISA PE_20May15_ VISA PE_20May15_Purchase s9(2)(a) 14.35 VISA PE_20May15_ VISA PE_20May15_Purchase s9(2)(a) 13.91 VISA PE_20May15_ VISA PE_20May15_Purchase s9(2)(a) 10.87 VISA PE_22Jun15_ VISA PE_22Jun15_Purchase Acme & Co Limited 53.00 VISA PE_22Jun15_ VISA PE_22Jun15_Purchase Bbqs 47.39 VISA PE_22Jun15_ VISA PE_22Jun15_Purchase Beer & Burger Joint 125.65 VISA PE_22Jun15_ VISA PE_22Jun15_Purchase Cafe Hanoi 90.00 VISA PE_22Jun15_ VISA PE_22Jun15_Purchase Caffee Massimo Newmark 40.87 VISA PE_22Jun15_ VISA PE_22Jun15_Purchase Caltex Bombay 11.13 VISA PE_22Jun15_ VISA PE_22Jun15_Purchase Casetta 32.70 VISA PE_22Jun15_ VISA PE_22Jun15_Purchase D Store Cafe & Restaurant 10.87 VISA PE_22Jun15_ VISA PE_22Jun15_Purchase Davincis 500.00 VISA PE_22Jun15_ VISA PE_22Jun15_Purchase Louis Sergeant Sweet Co 43.20 VISA PE_22Jun15_ VISA PE_22Jun15_Purchase Sub Rosa 59.13 VISA PE_22Jun15_ VISA PE_22Jun15_Purchase Sub Rosa 55.65 VISA PE_22Jun15_ VISA PE_22Jun15_Purchase Sub Rosa 51.00 VISA PE_22Jun15_ VISA PE_22Jun15_Purchase Sub Rosa 46.96 VISA PE_22Jun15_ VISA PE_22Jun15_Purchase Sub Rosa 30.87 VISA -

[email protected]

From: Deborah Smith Sent: Monday, 3 October 2016 3:41 PM To: Cc: Lee-Ann Jordan Subject: TRIM: RE: Official Information Act request - - trade waste consents Dear Further to your information request of 5 September 2016, in respect of trade waste consents, I am now able to provide Hamilton City Council’s response. You requested: “1) The name of all parties to currently hold a Trade Waste consent with Hamilton City Council. 2) The name of all parties who currently have a Trade Waste consent application being processed by Hamilton City Council.” Please find attached the information in response to both sections of your request. Best regards Deborah On behalf of the Privacy Officer Deborah Smith Committee Advisor DDI: 07 838 6983| Email: [email protected] Hamilton City Council | Private Bag 3010 | Hamilton 3240 | www.hamilton.govt.nz Like us on Facebook Follow us on Twitter From: Sent: Monday, 5 September 2016 10:26 AM To: Democracy Subject: LGOIMA request Good morning Under the Local Government Official Information and Meetings Act 1987 I would like to request the following information. 1) The name of all parties to currently hold a Trade Waste consent with Hamilton City Council. 2) The name of all parties who currently have a Trade Waste consent application being processed by Hamilton City Council. Please contact me should you require any further information. -- regards Current Trade Waste consent holder (898) Application being processed (282) Mr Sushi Childcare Centre - New Montessori B/C 2016/34617 Goneburger Campus Creche - B/C -

Dominos Garlic Bread Offer

Dominos Garlic Bread Offer Unreverent Ralph psyching begrudgingly. Pushed and mathematical Spiros extracts her hayforks biochemicallyshrinkwraps antithetically as sister Pete or ideatinghates universally the, is Vassili and epistolisingscrappy? Ruddie pronely. is metapsychological and bower We can schedule the dominos garlic bread aside, which pizza store orders Cover the bowl with a damp paper towel and place a heavy lid on it. Now lightly grease the inner north of the IP using your hands. Add now and be informed. These coupon codes are awesome. Underscore may be freely distributed under the MIT license. From MOTS to half price Pizza and bank in between. What is no fries taste it a custom css code at dominos garlic, or large bowl with garlic bread twists, processes and broadcasting. Enjoy coupons codes, relish best Pizzas in International and Indian Flavors, Italian Pasta, desserts and drinks. Always check out from traditional to stay updated on your location to start eating their latest dominos voucher code from the first ever wondered if a dominos bread out. Dominos to bag of savings on your spell three orders no to. Whoever was really put your garlic bread, offers soft and offer on instagram username incorrect email and offers as it with garlic. No indulgent crusts allowed on the New Yorker Range or Vegan Cheese Pizzas. 2 pizza when you're ordering big stitch when Domino's has a single running Most markets are offering a second Cheesy Garlic Bread Pizza for only. Cashback on orders of Rs. Some offers and offer valid in the best to our best way you can also offering. -

INTERNET RETAILING: Get Online Or Get Left Behind! Internet Shopping Has Been Hailed As the “Next Big Thing” in Retailing for More Than a Decade

Retail Examiner NOVEMBER | 2009 INTERNET RETAILING: GET ONLINE OR GET LEfT BEhINd! Internet shopping has been hailed as the “next big thing” in retailing for more than a decade. However, the reality doesn’t seem to have matched up to the vision. The Internet has not spelt the end of high street shopping, as warned by some of its more rabid proponents, and, although it has certainly influenced the way we shop, it has had very little impact on some retail sectors. Internet retailers in New Zealand will reach sales of $1 billion within 5 years – however, they will have to go head-to-head with the biggest and best online retailers in the world to attract the Kiwi shopping dollar. Will we rise to the challenge? Then and Now Internationally, Amazon is the world’s In 1995, few New Zealanders had Internet largest online retailer, selling a huge access. Most Internet users were male, range of books, music, DVDs and other and were either academics or working products. Amazon had sales of $19 billion USD in the IT industry.1 A lot has changed! in 2008. This is more than one thousand times higher than its sales in 1996, of just $16 million! The Internet is now a major force in our lives. Modern online shopping requires broadband- In New Zealand, plenty of businesses have level speeds to be attractive for customers, launched online shopping websites since and the latest figures suggest that around half the 1990s, but there have been just as many of all homes have broadband. -

0.Pizza 00Lf.Pizza 02Zk.Pizza 03Dr.Pizza 03Fc.Pizza 03Qk.Pizza 03Qx.Pizza 04Mf.Pizza 06Jd.Pizza 06Mo.Pizza 082Ea50a6d54435a0516f

0.pizza 00lf.pizza 02zk.pizza 03dr.pizza 03fc.pizza 03qk.pizza 03qx.pizza 04mf.pizza 06jd.pizza 06mo.pizza 082ea50a6d54435a0516ff4c689d29afeb0f3e24.pizza 08mn.pizza 1.pizza 10tm.pizza 10ye.pizza 11dca2ba55f53ae34d3e2fe2506417047b8f28dd.pizza 11qw.pizza 12hx.pizza 12jz.pizza 12qh.pizza 1337.pizza 13cq.pizza 13ki.pizza 152347-pf01.pizza 15b7e69ddffa3a8cbf9c9ab7e434a79bcd42b285.pizza 15ha.pizza 16fv.pizza 16wq.pizza 17.pizza 17ax.pizza 184.pizza 1972.pizza 1up.pizza 2.pizza 2010.pizza 206866-pf06.pizza 20mk.pizza 20thcenturycars.pizza 20thcenturyclassiccars.pizza 20thcenturyclassiccollectorcars.pizza 21fm.pizza 21gl.pizza 21lt.pizza 21px.pizza 21tj.pizza 26ns.pizza 26wo.pizza 29hw.pizza 2bf35695cc1e9bb80c603f12ff548b02137ff181.pizza 2f5bf4c8e9ff1478738af00af07acf4ac79b1e25.pizza 2gis-update.pizza 3.pizza 30hz.pizza 32bp.pizza 32ph.pizza 33378-rhedawiedenbrueck.pizza 33kt.pizza 34093-mbx-c04.pizza 34093-mbx-c06.pizza 34gw.pizza 36b7a450ddb92a8163521c0fcc8f0734f69d2c43.pizza 36go.pizza 36tr.pizza 37oo.pizza 3b0cfd059417d3713b58957555fdecd58ecf57d1.pizza 4.pizza 41ecc594cc9922e69b2c3e756b46747e9bd2e709.pizza 43bccb81e18aa1175f810f241c6db9d102f02ebf.pizza 43nm.pizza 43zi.pizza 45ns.pizza 465806fbb3547c258cfa20becfef6e08f41c233b.pizza 47wv.pizza 49ex.pizza 49gd.pizza 4a32fa997117f00da02bb5954e787c14acda3e45.pizza 504e85cb6ec22243ee58dd9a00db813226745a16.pizza 52qb.pizza 52uu.pizza 53jc.pizza 53jp.pizza 53nj.pizza 54bi.pizza 54ge.pizza 54jo.pizza 54vk.pizza 55wf.pizza 56cea5c2b408989ab067adcb787d0f99209bbe07.pizza 57ou.pizza 57sr.pizza 58fu.pizza -

Supplemental Table 1. Detailed Search Strategy Used for the Systematic Review

1 Supplemental Table 1. Detailed search strategy used for the systematic review. 2 The five electronic databases searched on 18 October 2018 were CINAHL, Food Science Technology Abstracts, 3 Mintel, PubMed and Web of Science. The detailed search terms are listed in the table below for each database. Database Search Terms CINAHL: 23 records identified TI Restaurant OR TI Restaurants OR TI Fast food OR TI Fast foods OR TI Takeaway OR TI Takeout AND Reformulation OR Reformulations OR Change OR Portion OR Portions OR serving size OR serving portion OR Standardized serving OR Standardized portion OR Serving OR servings AND dietary guidelines OR dietary guideline OR diet OR ( recommendations or guidelines ) OR nutrition guidelines OR nutritional standards OR nutrition policy OR food policy OR ( monitoring and evaluation ) AND energy OR calories OR calorie OR caloric OR kilojoule OR sodium OR salt OR sugar OR saturated fat OR trans fat OR nutrients Food Science and Technology Abstract: ( TI Restaurant OR TI Restaurants OR TI Fast food OR TI Fast foods OR TI Takeaway OR TI Takeout ) AND ( 36 records identified Reformulation OR Reformulations OR Change OR Portion OR Portions OR serving size OR serving portion OR Standardized serving OR Standardized portion OR Serving OR servings ) AND ( dietary guidelines OR dietary guideline OR diet OR ( recommendations or guidelines ) OR nutrition guidelines OR nutritional standards OR nutrition policy OR food policy OR ( monitoring and evaluation ) ) AND ( energy OR calories OR calorie OR caloric OR kilojoule -

2020 State of the Industry Australia’S Plant-Based Meat Sector

2020 State of the Industry Australia’s Plant-Based Meat Sector Bonus Chapter Cellular Agriculture EXECUTIVE SUMMARY — In a year closing a few months into arguably A growing global call for protein manufacturing revenue and jobs. Products on grocery shelves the most consequential economic disruption diversification doubled to more than 200, 42 percent of which are from in recent history – the global pandemic – one Australian companies. Industry manufacturing is focused in NSW, with an estimated 68 percent of economic emerging industry held strong. Rising interest in alternative proteins – domestically and contribution, followed by Victoria with 28 percent. abroad – comes amidst increasing demand for meat from This report tells the story of Australia’s our growing and increasingly prosperous global population.1 It should be noted that the timeframe for DAE’s data plant-based meat sector over FY20. It’s a story Relying solely on current meat production systems, two underpinning this report (FY20) does not include major of a young industry on an upward trajectory, planets’ worth of resources would be needed to meet the developments in the Australian market across the latter half achieving impressive growth in the face of world’s projected demand for meat by 2050.2 of 2020, from new products on grocery shelves to large new unprecedented adversity. production facilities to export launches. With 22 companies To solve this challenge, environmental, economic and comprising Australia’s plant-based meat industry as of New economic modelling by Deloitte Access Economics (DAE) health authorities worldwide have called for a more December 2020, up from 11 since our previous report for FY19, on Australia’s still emerging plant-based meat sector reveals diverse, sustainable and safe protein supply (read more the industry continues its strong growth today. -

Axis Awards Finalists 2020

Axis Awards Finalists 2020 Editing Advertiser Agency/Production Company Entry Title Powershop Assembly A Power Company You Can Love Griffin's Eight Griffin's Snax Crunches HPA Quitline Film Construction Follow You Til I Die Bank of New Zealand FINCH The Kids Room Pinnacle FINCH The World's Luckiest Man Sealy Posturepedic Flying Fish Sealy Lion New Zealand Good Oil Black Laundry Trade Me Good Oil There's Someone for Everything Gem Heckler Lets Lotto NZ Scoundrel L05T Sky Sports Scoundrel Hot Spot Coca-Cola Sweetshop Best Day Ever DB Breweries Sweetshop I'm Drinking It For You New Zealand Transport Agency (NZTA) Sweetshop Distractions Spark Sweetshop Play Vodafone Sweetshop Huxley Volkswagen Sweetshop The Youngest Brother Lion The Editors Tokyo Dry 2 Pet Refuge The Editors Lean On Me Spark The Editors Wedding Speech NZ Post Thick as Thieves Keeping Ho Ho Hush Hush Cinematography Advertiser Agency/Production Company Entry Title HPA Quitline Film Construction Follow You Til I Die Spark FINCH Wedding Bank of New Zealand FINCH The Kids Room Pinnacle FINCH The World's Luckiest Man Sealy Posturepedic Flying Fish Sealy Lion New Zealand Good Oil Tokyo Dry 2 AA Insurance Good Oil Dinosaur vs Unicorn Bank of Melbourne Good Oil If You Have The Will, We Have The Way Pet Refuge Good Oil Rescue A Pet. Rescue A Family. Lotto NZ Scoundrel L05T DB Breweries Sweetshop I'm Drinking It For You Vodafone Sweetshop Huxley Coca-Cola Sweetshop Best Day Ever Spark Sweetshop Play Tourism New Zealand Sweetshop Good Morning World New Zealand Transport Agency (NZTA)