HEP Letterhead Template

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Residential Research

RESIDENTIAL RESEARCH THE DOWNSIZING LIFESTYLE TREND TOWARDS LUXURY APARTMENT LIVING Rightsizing beyond 2020 -Page 2 Dwelling migration routes The strong demand from downsizers Rightsizing also appeals to younger -Page 3 seeking easily maintainable prime generations, and we see this at a much properties close to city centre locations earlier stage than in previous years given Buyer profile of prime apartments has been identified as one of nine global the agile, transient and global nature of -Page 4 trends being monitored over the coming our work and play. years, as identified in the Knight Frank Prime Global Forecast 2020. Apartment living allows for low Trends in prime apartments maintenance living when at home, -Page 5 When working with our clients, many tell convenience of concierge and the ability us their home is no longer required to of lock-up-and-leave when away. provide the lifestyle they once had, and Pipeline of new dwellings in prime more often, the cost to upkeep This prime trend follows a similar path to suburbs -Page 7 outweighs the surplus space once the wider market with the average new desired. house size built in 2018/19 falling 1.3% on the year before, whilst the average Owning strata titled property With this new active retiree lifestyle, they new apartment size grew by 3.2%, -Page 8 seek simplicity, and to feel the vibe from according to the Australian Bureau of living close to the action. Downsizing the Statistics (ABS) when commissioned by Case study: The cost to upkeep living areas is not part of this movement CommSec. -

AVANT at Met Square

january 2016 volume XVIII AVANT at met square the next generation of urban living SUSTAINED MOMENTUM The U.S. economy remains healthy, with more than 2.8 million new jobs added during the 12 months ending October 2015. U.S. homeownership continues to decline, and at 63.7% percent, hovers near historic lows. These positive trends are continuing to drive rental demand. The third quarter of 2015 was the seventh consecutive quarter of positive net unit absorption. On average, rent growth registered 5.2 percent in the major U.S. markets, and the vacancy rate was 4.3 percent, the lowest level of the current cycle. Industry analysts expect that new unit production will peak in 2016, before tapering through the end of the decade. The near term increase in new supply is expected to have only modest impacts on vacancy and rent growth. However, due to continued job growth and a steady influx of new renters, primarily millennials entering the rental market and aging baby boomers who increasingly find rental housing more attractive than homeownership, the market will continue to perform well. With these positive market forces at work, ZOM is poised for continued success in 2016. In Florida, we will complete lease-ups at Moda and Bel Air Doral in early 2016, and will begin delivering units at Monarc at Met 3, Baldwin Harbor, Delray Preserve, and Luzano. In Texas, our Tate project in Houston will also open its doors. In our Mid-Atlantic region, construction continues at Banner Hill in Baltimore, and we are working on several new projects in other Mid-Atlantic target markets. -

Pacifying Paradise: Violence and Vigilantism in San Luis Obispo

PACIFYING PARADISE: VIOLENCE AND VIGILANTISM IN SAN LUIS OBISPO A Thesis presented to the Faculty of California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in History by Joseph Hall-Patton June 2016 ii © 2016 Joseph Hall-Patton ALL RIGHTS RESERVED iii COMMITTEE MEMBERSHIP TITLE: Pacifying Paradise: Violence and Vigilantism in San Luis Obispo AUTHOR: Joseph Hall-Patton DATE SUBMITTED: June 2016 COMMITTEE CHAIR: James Tejani, Ph.D. Associate Professor of History COMMITTEE MEMBER: Kathleen Murphy, Ph.D. Associate Professor of History COMMITTEE MEMBER: Kathleen Cairns, Ph.D. Lecturer of History iv ABSTRACT Pacifying Paradise: Violence and Vigilantism in San Luis Obispo Joseph Hall-Patton San Luis Obispo, California was a violent place in the 1850s with numerous murders and lynchings in staggering proportions. This thesis studies the rise of violence in SLO, its causation, and effects. The vigilance committee of 1858 represents the culmination of the violence that came from sweeping changes in the region, stemming from its earliest conquest by the Spanish. The mounting violence built upon itself as extensive changes took place. These changes include the conquest of California, from the Spanish mission period, Mexican and Alvarado revolutions, Mexican-American War, and the Gold Rush. The history of the county is explored until 1863 to garner an understanding of the borderlands violence therein. v TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CHAPTER INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………... 1 PART I - CAUSATION…………………………………………………… 12 HISTORIOGRAPHY……………………………………………........ 12 BEFORE CONQUEST………………………………………..…….. 21 WAR……………………………………………………………..……. 36 GOLD RUSH……………………………………………………..….. 42 LACK OF LAW…………………………………………………….…. 45 RACIAL DISTRUST………………………………………………..... 50 OUTSIDE INFLUENCE………………………………………………58 LOCAL CRIME………………………………………………………..67 CONCLUSION………………………………………………………. -

Old Spanish National Historic Trail Final Comprehensive Administrative Strategy

Old Spanish National Historic Trail Final Comprehensive Administrative Strategy Chama Crossing at Red Rock, New Mexico U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service - National Trails Intermountain Region Bureau of Land Management - Utah This page is intentionally blank. Table of Contents Old Spanish National Historic Trail - Final Comprehensive Administrative Stratagy Table of Contents i Table of Contents v Executive Summary 1 Chapter 1 - Introduction 3 The National Trails System 4 Old Spanish National Historic Trail Feasibility Study 4 Legislative History of the Old Spanish National Historic Trail 5 Nature and Purpose of the Old Spanish National Historic Trail 5 Trail Period of Significance 5 Trail Significance Statement 7 Brief Description of the Trail Routes 9 Goal of the Comprehensive Administrative Strategy 10 Next Steps and Strategy Implementation 11 Chapter 2 - Approaches to Administration 13 Introduction 14 Administration and Management 17 Partners and Trail Resource Stewards 17 Resource Identification, Protection, and Monitoring 19 National Historic Trail Rights-of-Way 44 Mapping and Resource Inventory 44 Partnership Certification Program 45 Trail Use Experience 47 Interpretation/Education 47 Primary Interpretive Themes 48 Secondary Interpretive Themes 48 Recreational Opportunities 49 Local Tour Routes 49 Health and Safety 49 User Capacity 50 Costs 50 Operations i Table of Contents Old Spanish National Historic Trail - Final Comprehensive Administrative Stratagy Table of Contents 51 Funding 51 Gaps in Information and -

Parc Huron Becomes Chicago's First LEED Gold High Rise Apartment

Friday, August 27, 2010 FOR: Parc Huron RMK Management Corp. Parc Huron Becomes Chicago’s First LEED Gold High Rise Apartment Building Luxury rental building first in Illinois, one of only a handful in the country Chicago-based M&R Development and RMK Management Corp. have announced their newest luxury apartment community, Parc Huron, located at 469 W. Huron St. in Chicago’s River North neighborhood, as the first of its kind in the city to earn LEED Gold certification from the U.S. Green Building Council (USGBC). To earn this nationally respected accreditation, Parc Huron’s design, construction and operation must meet the strict standards set forth by the USGBC, including a high level of energy and water efficiency; use of recycled and regional materials and recyclable construction materials; and an advanced degree of indoor air quality, which is attained through the use of low-VOC materials and a sophisticated air filtration system. Additional credits were earned for the development of an adjacent park, a green roof, extensive use of natural light throughout the units and the common areas, and for the walkable location in the heart of River North. “We are thrilled to be the first LEED Gold certified rental high rise in Illinois, and are even more excited to offer this type of residence to the people of Chicago,” said Anthony Rossi, Sr., president of RMK Management Corp. “Chicago has long been known as a leader in terms of art, fashion and architecture, and we continue to be ahead of the trend for high-end green living, too.” Rossi noted that the apartment homes, in addition to being exceptionally eco-friendly, offer upscale features on par with for-sale condominiums. -

Residential Hotels in Chicago, 1880-1930

NPS Form 10-900-b OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form This form is used for documenting property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin How to Complete the Multiple Property Documentation Form (formerly 16B). Complete each item by entering the requested information. __x_____ New Submission ________ Amended Submission A. Name of Multiple Property Listing Residential Hotels in Chicago, 1880-1930 B. Associated Historic Contexts (Name each associated historic context, identifying theme, geographical area, and chronological period for each.) The Evolution of the Residential Hotel in Chicago as a Distinct Building Type (1880-1930) C. Form Prepared by: name/title: Emily Ramsey, Lara Ramsey, w/Terry Tatum organization: Ramsey Historic Consultants street & number: 1105 W. Chicago Avenue, Suite 201 city or town: Chicago state: IL zip code: 60642 e-mail: [email protected] telephone: 312-421-1295 date: 11/28/2016 D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National Register documentation standards and sets forth requirements for the listing of related properties consistent with the National Register criteria. This submission meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR 60 and the Secretary of the Interior’s Standards and Guidelines for Archeology and Historic Preservation. _______________________________ _______________________________________________ Signature of certifying official Title Date _____________________________________ State or Federal Agency or Tribal government I hereby certify that this multiple property documentation form has been approved by the National Register as a basis for evaluating related properties for listing in the National Register. -

Cleveland Heights RFQ

Request for Qualifications and Preliminary Development Proposals RFQ/RFP – Top of Hill Site Presented to: City of Cleveland Heights 40 Severance Circle Cleveland Heights, OH 44118 For More Information Contact: Deron Kintner General Counsel Flaherty & Collins Properties [email protected] 317.816.9300 www.flco.com May 23, 2016 Flaherty & Collins Properties (F&C) is pleased to submit this Request for Qualifications and Development Proposal to the City of Cleveland Heights for the development of the Top of the Hill site. As Developer, F&C will develop the Project in the same manner as the projects outlined in this proposal. For the reasons stated in this submission, F&C believes its extensive experience and proven track record make us the best and most uniquely qualified developer to undertake this complex and exciting development. If selected, F&C commits to deliver a first-class, high-quality, innovative mixed-use development in a timely and efficient manner. We believe we are the best and most qualified developer to execute and deliver upon this development. The materials to follow provide more detail to support each of these points. • Corporate Experience. F&C, which has over 450 employees, has developed 58 projects and more than 8,500 units in the past 15 years with a value in excess of $1 billion, currently manages over 15,500 units in 13 states and has been involved with the construction of over 15,000 units in 20 states. F&C is fully integrated with in-house development, construction and property management professionals and has the ability to structure, procure and close complicated, multi-layered financing. -

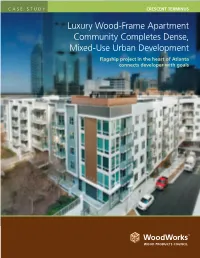

Luxury Wood-Frame Apartment Community Completes Dense, Mixed-Use Urban Development Flagship Project in the Heart of Atlanta Connects Developer with Goals

FRONT COVER CASE STUDY CRESCENT TERMINUS Luxury Wood-Frame Apartment Community Completes Dense, Mixed-Use Urban Development Flagship project in the heart of Atlanta connects developer with goals $FRA-490_CrescentTerminus_CaseStudy.indd 3 3/13/15 4:18 PM Surrounded by high-rise buildings in the upscale Buckhead neighborhood of Atlanta, Crescent Terminus is a new three-building, luxury apartment complex offering resort-style amenities, including a salt-water pool, rooftop terraces with dramatic skyline views, a gourmet coffee bar and more. Featuring five stories of wood over a concrete podium, the project fills the last three parcels of land in the Terminus complex, completing this unique urban development. And while the prime piece of real estate carried a corresponding price tag, the developer was able to move ahead with the project thanks in large part to the choice of an affordable, high-quality wood-frame structure. 2 $FRA-490_CrescentTerminus_CaseStudy.indd 2 3/13/15 4:18 PM CRESCENT TERMINUS “This site has all the ingredients for a successful luxury apartment community,” said Jay Curran, Vice President of Crescent Project Overview Communities’ multi-family group. “Its location in the heart of Buckhead is ideal. Surrounded by world-class office space, luxury condominiums, outstanding public art, five-star dining and street- level retail, Crescent Terminus will offer a unique lifestyle that allows residents an opportunity to work, play and live all within easy walking distances. This location and all those attributes are consistent with the Crescent brand of exceptional development.” The Crescent Terminus project was inspired through extensive review and analysis of current industry trends and marketplace needs. -

Mission San Gabriel Arcangel Ssion Boulevard Gabriel, Los Angeles, California

,, No. ~37-8 H Mission San Gabriel Arcangel ssion Boulevard Gabriel, Los Angeles, California PH'.JTOGHAPI-L3 WRITTEN HL3TORICAL AND DESCHIPTIVI<~ DATA District of California #3 Historic American Buildings durvey Henry F. Withey, District Officer 407 So. Western Avenue Los Angeles, California. MISSION SAN GABRIEL ARCANGEL HABS. No. 37-8 Mission Boulevard' San Gabriel, Los Angeles County California.. SHOP RUINS HABS. No. 37-SA HA,B5 t.A L. Owner: Roman Catholio Arohbishop, Diocese of Los Angeles, 1114'"1!/est Olympia Blvd., Los Angeles, California Date of ereotion Present ohuroh started 1794 - oompleted 1806. Arohi tect: Padre Antonio Curzad o. Builder: Indian labor under direction of Padres Cil.rzado. and Sanohez . l?Jisent Conditions: Of the buildtngs that composed the original group, there remain, the Church, i'he Padres' Living Quarters, an adjoining Kitchen, and foundations of a Tannery, Soap Factory and Smithy. The ohuroh is in fair oondition, and still serves the oommunity as a Catholic Church. The Padres' Quarters is also in :fair condition, and is used aa a Museum for the display of Mission relios, the sale of cards, pictures and· souvenirs of the Mission, and for storage purposes. The shop foundations aee in a ruined condition. Number of stories: The ohurch is a high one-story structure with a choir balcony at the east end. :Materials of construotion1 Foundations of all remaining buildings are of fieldstonea, laid in lime mortar. Walls of the church are part stone, part burned brick, laid in lime mortar and thinly plast ered both sides.· Floors are of wood; roof over Baptist;ry and Saortatfy are of stone laid in lime mortar. -

Historical Resources Survey for the San Diego Fire-Rescue Air Operations Hangar Project (WBS #B-15012.02.02)

Historical Resources Survey for the San Diego Fire-Rescue Air Operations Hangar Project (WBS #B-15012.02.02) Prepared for City of San Diego Submitted to Platt/Whitelaw Architects, Inc. 4034 30th Street San Diego, CA 92104 Contact: Mr. Thomas Brothers Prepared by RECON Environmental, Inc. 1927 Fifth Avenue San Diego, CA 92101 P 619.308.9333 RECON Number 9078 December 16, 2019 Carmen Zepeda-Herman, M.A., Project Archaeologist Historical Resources Survey ARCHAEOLOGICAL RESOURCE REPORT FORM I. PROJECT DESCRIPTION AND LOCATION Phase II of the San Diego’s Fire-Rescue Air Operations (AirOps) Facility Project (proposed project) would design and construct permanent helicopter hangars and support facilities at Montgomery-Gibbs Executive Airport. The project area is located in the northeastern corner of the airport in the Kearny Mesa community of the city of San Diego, California (Figure 1). The project area is within an unsectioned portion of the Mission San Diego landgrant on the U.S. Geological Survey 7.5-minute La Jolla quadrangle (Figure 2). Figure 3 shows the project location on a City 800’ map. The project area consists of a 6.5-acre site located adjacent to the Air Traffic Control Tower between the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) lease area, the Runway Object Free Area, and the Runway Protection Zone for the northwest approach to Runway 5/23 (Figure 4). Entry to the project area is via an asphalt road accessed from a security gate located off Ponderosa Avenue. AirOps is a 24/7 365-day operating facility with no hangar space at Montgomery Field. A feasibility study concluded that 30,000 square feet of hangar space is required to meet future needs of the AirOps fleet. -

Section 3.9 Archaeological and Paleontological Resources

SECTION 3.9 ARCHAEOLOGICAL/PALEONTOLOGICAL RESOURCES 3.9 ARCHAEOLOGICAL/PALEONTOLOGICAL RESOURCES 3.9.1 INTRODUCTION This section examines the potential impacts to arctlaeological and paleontological resources, including Native American cultural resources, that may result from the Proposed Project, and is based on the Archaeological and Paleontolog~caI Resources Technical Report prepKred by DLIDEK (May 2009). As further explained below, any potential impacts to archaeological and paleontological resources would be mitigated to a level below significant. The technical report relied upon for pro-par afion of this section is included in Appendix 3.9 of tl~s ELR. 3.9.2 METHODOLOGY 3.9.2.1 Archaeological Resources An occchaeological records search of data maintained at the South Coastal Archaeological Information Center ("SCIAC") was requested on April 16, 2009, ai~d SCIAC completed the records search on April 21, 2009. The records search, which included the review of relevant archaeological report and site record databases, extended to all areas within 0.25 mile of tlie Project site. (Please see AppenctKx A of the technica~ report, located in Appendix 3.9, for a list of the reports and records identified during the records search.) 3.9.2.2 Paleontological Resources The paleontologicai resource investigation relied on the foliowing documents: Geology of the San Diego Metropolitan Area, California (Kennedy and Petorson, 1975); Geotechnical Input for Environmental Impact Report (Southloa~d Geotechnical Consultants (SGC), 2009; see Appendix 3.4); and Paleontological Resources, County of San Diego (Demhr~ and Walsh, 1993). 3.9.2.3 Native American Cultural Resources In order to assess the potential impacts to Native American cnfturaI resources, a letter (dated ApriI 15, 2009) was sent to the Native American Heritage Corm~ssion ("NAHC") requesti~lg: (i) fl~at a Sacred Lands F~Ie search be conducted for the Project site and neighboring vicirdty; and (ti) that a list of local tribal contacts be provided. -

2013 Historic Sites Directory

2013 www.californiamissionsfoundation.org HISTORIC SITES DIRECTORY MISSION SAN DIEGO MISSION SAN ANTONIO DE PADUA ASISTENCIA SAN ANTONIO DE PALA 10818 San Diego Mission Rd. End of Mission Creek Rd. PALA RESERVATION San Diego, CA 92108 P.O. Box 803 P.O. BOX M (619) 283-7319 Jolon, CA 93928 PALA, CA 92059 (831) 385-4478 (760) 742-3317 MISSION SAN LUIS REY 4050 Mission Avenue MISSION SOLEDAD EL PRESIDIO DE SANTA BARBARA Oceanside, CA 92057 36641 Fort Romie Rd. 123 E. CANON PERDIDO ST. (760) 757-3651 Soledad, CA 93960 SANTA BARBARA, CA 93102 (831) 678-2586 (805) 965-0093 MISSION SAN JUAN CAPISTRANO 26801 Ortega Highway MISSION CARMEL ROYAL PRESIDIO CHAPEL OF MONTEREY San Juan Capistrano, CA 92675 3080 Rio Rd. 500 CHURCH ST. (949) 234-1300 Carmel, CA 93923 MONTEREY, CA 93940 (831) 624-3600 (831) 373-2628 MISSION SAN GABRIEL 428 South Mission Dr. MISSION SAN JUAN BAUTISTA San Gabriel, CA 91776 406 Second St. (626) 457-7291 P.O. Box 400 San Juan Bautista, CA 95045 MISSION SAN FERNANDO (831) 623-2127 15151 San Fernando Mission Blvd. Mission Hills, CA 91345 MISSION SANTA CRUZ (818) 361-0186 126 High St. Santa Cruz, CA 95060 MISSION SAN BUENAVENTURA (831) 426-5686 211 East Main St. Ventura, CA 93001 MISSION SANTA CLARA (805) 643-4318 500 El Camino Real Santa Clara, CA 95053 MISSION SANTA BARBARA (408) 554-4023 2201 Laguna St. Santa Barbara, CA 93105 MISSION SAN JOSE (805) 682-4713 P.O. Box 3159 Fremont, CA 94539 MISSION SANTA INES (510) 657-1797 1760 Mission Dr.