The Divine Comedy Purgatorio

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aerospace Dimensions Leader's Guide

Leader Guide www.capmembers.com/ae Leader Guide for Aerospace Dimensions 2011 Published by National Headquarters Civil Air Patrol Aerospace Education Maxwell AFB, Alabama 3 LEADER GUIDES for AEROSPACE DIMENSIONS INTRODUCTION A Leader Guide has been provided for every lesson in each of the Aerospace Dimensions’ modules. These guides suggest possible ways of presenting the aerospace material and are for the leader’s use. Whether you are a classroom teacher or an Aerospace Education Officer leading the CAP squadron, how you use these guides is up to you. You may know of different and better methods for presenting the Aerospace Dimensions’ lessons, so please don’t hesitate to teach the lesson in a manner that works best for you. However, please consider covering the lesson outcomes since they represent important knowledge we would like the students and cadets to possess after they have finished the lesson. Aerospace Dimensions encourages hands-on participation, and we have included several hands-on activities with each of the modules. We hope you will consider allowing your students or cadets to participate in some of these educational activities. These activities will reinforce your lessons and help you accomplish your lesson out- comes. Additionally, the activities are fun and will encourage teamwork and participation among the students and cadets. Many of the hands-on activities are inexpensive to use and the materials are easy to acquire. The length of time needed to perform the activities varies from 15 minutes to 60 minutes or more. Depending on how much time you have for an activity, you should be able to find an activity that fits your schedule. -

Chance, Luck and Statistics : the Science of Chance

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Alberta Gambling Research Institute Alberta Gambling Research Institute 1963 Chance, luck and statistics : the science of chance Levinson, Horace C. Dover Publications, Inc. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/41334 book Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca Chance, Luck and Statistics THE SCIENCE OF CHANCE (formerly titled: The Science of Chance) BY Horace C. Levinson, Ph. D. Dover Publications, Inc., New York Copyright @ 1939, 1950, 1963 by Horace C. Levinson All rights reserved under Pan American and International Copyright Conventions. Published in Canada by General Publishing Company, Ltd., 30 Lesmill Road, Don Mills, Toronto, Ontario. Published in the United Kingdom by Constable and Company, Ltd., 10 Orange Street, London, W.C. 2. This new Dover edition, first published in 1963. is a revised and enlarged version ot the work pub- lished by Rinehart & Company in 1950 under the former title: The Science of Chance. The first edi- tion of this work, published in 1939, was called Your Chance to Win. International Standard Rook Number: 0-486-21007-3 Libraiy of Congress Catalog Card Number: 63-3453 Manufactured in the United States of America Dover Publications, Inc. 180 Varick Street New York, N.Y. 10014 PREFACE TO DOVER EDITION THE present edition is essentially unchanged from that of 1950. There are only a few revisions that call for comment. On the other hand, the edition of 1950 contained far more extensive revisions of the first edition, which appeared in 1939 under the title Your Chance to Win. One major revision was required by the appearance in 1953 of a very important work, a life of Cardan,* a brief account of whom is given in Chapter 11. -

Building Cold War Warriors: Socialization of the Final Cold War Generation

BUILDING COLD WAR WARRIORS: SOCIALIZATION OF THE FINAL COLD WAR GENERATION Steven Robert Bellavia A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2018 Committee: Andrew M. Schocket, Advisor Karen B. Guzzo Graduate Faculty Representative Benjamin P. Greene Rebecca J. Mancuso © 2018 Steven Robert Bellavia All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Andrew Schocket, Advisor This dissertation examines the experiences of the final Cold War generation. I define this cohort as a subset of Generation X born between 1965 and 1971. The primary focus of this dissertation is to study the ways this cohort interacted with the three messages found embedded within the Cold War us vs. them binary. These messages included an emphasis on American exceptionalism, a manufactured and heightened fear of World War III, as well as the othering of the Soviet Union and its people. I begin the dissertation in the 1970s, - during the period of détente- where I examine the cohort’s experiences in elementary school. There they learned who was important within the American mythos and the rituals associated with being an American. This is followed by an examination of 1976’s bicentennial celebration, which focuses on not only the planning for the celebration but also specific events designed to fulfill the two prime directives of the celebration. As the 1980s came around not only did the Cold War change but also the cohort entered high school. Within this stage of this cohorts education, where I focus on the textbooks used by the cohort and the ways these textbooks reinforced notions of patriotism and being an American citizen. -

THE DIVINE COMEDY Dante Alighieri

THE DIVINE COMEDY dante alighieri A new translation by J.G. Nichols With twenty-four illustrations by Gustave Doré ALMA CLASSICS alma classics ltd London House 243-253 Lower Mortlake Road Richmond Surrey TW9 2LL United Kingdom www.almaclassics.com This translation of the entire Divine Comedy first published by Alma Classics Ltd in 2012 The translation of Inferno first published by Hesperus Press in 2005; published in a revised edition by Alma Classics Ltd (previously Oneworld Classics Ltd) in 2010 The translation of Purgatory first published by Alma Classics Ltd (previously Oneworld Classics Ltd) in 2011 Translation, notes and extra material © J.G. Nichols, 2012 Cover image: Gustave Doré Printed in Great Britain by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, cr0 4yy Typesetting and eBook conversion by Tetragon isbn: 978-1-84749-246-3 All the pictures in this volume are reprinted with permission or pre sumed to be in the public domain. Every effort has been made to ascertain and acknowledge their copyright status, but should there have been any unwitting oversight on our part, we would be happy to rectify the error in subsequent printings. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechani- cal, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not be resold, lent, hired out or otherwise circulated without the express prior consent of the publisher. CONTENTS The Divine Comedy 1 Inferno 3 Purgatory 165 Paradise 329 Extra Material 493 Dante Alighieri’s Life 495 Dante Alighieri’s Works 498 Inferno 501 Purgatory 504 Paradise 509 Select Bibliography 516 Note on the Text and Acknowledgements 517 Index 519 CANTO I This canto, the prologue to Dante’s journey through the Inferno, acts also as an introduction to The Divine Comedy as a whole. -

Dante's Political Life

Bibliotheca Dantesca: Journal of Dante Studies Volume 3 Article 1 2020 Dante's Political Life Guy P. Raffa University of Texas at Austin, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/bibdant Part of the Ancient, Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque Art and Architecture Commons, Italian Language and Literature Commons, and the Medieval History Commons Recommended Citation Raffa, Guy P. (2020) "Dante's Political Life," Bibliotheca Dantesca: Journal of Dante Studies: Vol. 3 , Article 1. Available at: https://repository.upenn.edu/bibdant/vol3/iss1/1 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/bibdant/vol3/iss1/1 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Raffa: Dante's Political Life Bibliotheca Dantesca, 3 (2020): 1-25 DANTE’S POLITICAL LIFE GUY P. RAFFA, The University of Texas at Austin The approach of the seven-hundredth anniversary of Dante’s death is a propi- tious time to recall the events that drove him from his native Florence and marked his life in various Italian cities before he found his final refuge in Ra- venna, where he died and was buried in 1321. Drawing on early chronicles and biographies, modern historical research and biographical criticism, and the poet’s own writings, I construct this narrative of “Dante’s Political Life” for the milestone commemoration of his death. The poet’s politically-motivated exile, this biographical essay shows, was destined to become one of the world’s most fortunate misfortunes. Keywords: Dante, Exile, Florence, Biography The proliferation of biographical and historical scholarship on Dante in recent years, after a relative paucity of such work through much of the twentieth century, prompted a welcome cluster of re- flections on this critical genre in a recent volume of Dante Studies. -

How Complicated Can Structures Be? NAW 5/9 Nr

1 1 Jouko Väänänen How complicated can structures be? NAW 5/9 nr. 2 June 2008 117 Jouko Väänänen University of Amsterdam Plantage Muidergracht 24 1018 TV Amsterdam The Netherlands [email protected] How complicated can structures be? Is there a measure of how ’close’ non-isomorphic mathematical structures are? Jouko functions f : N → N endowed with the topolo- Väänänen, professor of logic at the Universities of Amsterdam and Helsinki, shows how con- gy of pointwise convergence, where N is given temporary logic, in particular set theory and model theory, provides a vehicle for a meaningful the discrete topology. discussion of this question. As the journey proceeds, we accelerate to higher and higher We can now consider the orbit of an arbi- cardinalities, so fasten your seatbelts. trary countable structure under all permuta- tions of N and ask how complex this set is By a structure we mean a set endowed with a eyes of the difficult uncountable structures. in the topological space N. If the orbit is a finite number of relations, functions and con- New ideas are needed here and a lot of work closed set in this topology, we should think of stants. Examples of structures are groups, lies ahead. Finally we tie the uncountable the structure as an uncomplicated one. This fields, ordered sets and graphs. Such struc- case to stability theory, a recent trend in mod- is because the orbit being closed means, in tures can have great complexity and indeed el theory. It turns out that stability theory and view of the definition of the topology, that the this is a good reason to concentrate on the the topological approach proposed here give finite parts of the structure completely deter- less complicated ones and to try to make similar suggestions as to what is complicated mine the whole structure, as is easily seen to some sense of them. -

The Transformation of Arachne Into a Spider.Pdf

Name: Class: The Transformation of Arachne into a Spider By Ovid From Metamorphoses (Book Vi) 8 A.D. Ovid (43 B.C.-17 A.D.) was a Roman poet well-known for his elaborate prose and fantastical imagery. Ovid was similar to his literary contemporary, Virgil, in that both authors played a part in reinventing classical poetry and mythology for Roman culture. Metamorphoses, one of Ovid’s most-read works, consists of a series of short stories and epic poems whose mythological characters undergo transformation in some way or another. As you read, take notes on Ovid’s choice of figurative language and imagery. [1] Pallas,1 attending to the Muse's2 song, Approv'd the just resentment of their wrong; And thus reflects: While tamely3 I commend Those who their injur'd deities4 defend, [5] My own divinity affronted stands, And calls aloud for justice at my hands; Then takes the hint, asham'd to lag behind, And on Arachne' bends her vengeful mind; One at the loom5 so excellently skill'd, [10] That to the Goddess6 she refus'd to yield. Low was her birth, and small her native town, She from her art alone obtain'd renown. Idmon, her father, made it his employ, "Linen Weaving" is licensed under CC BY-ND 2.0. To give the spungy fleece7 a purple dye: [15] Of vulgar strain her mother, lately dead, With her own rank had been content to wed; Yet she their daughter, tho' her time was spent In a small hamlet,8 and of mean descent, Thro' the great towns of Lydia gain'd a name, [20] And fill'd the neighb'ring countries with her fame. -

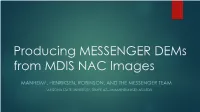

Producing MIDS NAC Dems from MESSENGER Images

Producing MESSENGER DEMs from MDIS NAC Images MANHEIM1, HENRIKSEN, ROBINSON, AND THE MESSENGER TEAM 1ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY, TEMPE AZ—[email protected] Launched: August 2004 MESSENGER Mercury Orbit: March 2011 Completed: April 2015 Mercury Dual Imaging System (MDIS) 2 framing cameras: a monochrome NAC and a multispectral WAC NAC wasn’t a stereo camera, but off-nadir observations enable the creation of DEMs NACs have 5 m pixel scale at closest approach Mercury Laser Altimeter (MLA) Radial accuracy of < 20 m Only available between 90° N and 18° S Highly Elliptical Orbit Periapsis: 200 – 500 km (near North Pole) Apoapsis: 10,000 – 15,000 km Methodology: Overview Site Selection & Image Selection Illumination Conditions Imaging Geometry DEM Production Using the USGS Integrated Software for Imagers and Spectrometers (ISIS) and SOCET SET 5.6 Error analysis Creating data products for PDS release Image Selection Selecting stereo images requires compromise between finding optimal images and building up desired coverage. These parameters will dictate the precision of the final product. Strength of stereo: parallax between the two images / unit height Illumination compatibility: distance between the tips of shadows in two images / unit height *Guidelines adapted from Becker, et al. 2015. Images Selected for Our DEMs n=49 Selecting Images to Build Mosaics Sander Crater mosaic: 21 images Selecting Images to Build Mosaics Sander Crater mosaic: 21 images 36 stereo pairs (areas of overlap producing ‘good’ stereo) Selecting Images to Build Mosaics Sander Crater mosaic: 21 images 36 stereo pairs (areas of overlap producing ‘good’ stereo) Resulting DEMs can be mosaicked together (using ISIS) to create one large-area DEM Processing in SOCET SET: Overview Import into SOCET SET 5.6 Relative Triangulation Registration to MLA tracks DEM Extraction Orthophoto Generation Creating Additional Data Products PDS Release *This process is quite similar to that described for LROC NAC DEMs in Henriksen, et al. -

Download a Pdf File of This Issue for Free

Issue 70: Dante's Guide to Heaven and Hell Dante and the Divine Comedy: Did You Know? What a famous painting suggests about Dante's life, legend, and legacy. Big Man in the Cosmos A giant in the world of which he wrote, laurel-crowned Dante stands holding his Divine Comedy open to the first lines: "Midway this way of life we're bound upon, / I woke to find myself in a dark wood, / Where the right road was wholly lost and gone." Of course, his copy reads in Italian. Dante was the first major writer in Christendom to pen lofty literature in everyday language rather than in formal Latin. Coming 'Round the Mountain Behind Dante sits multi-tiered Mount Purgatory. An angel guards the gate, which stands atop three steps: white marble for confession, cracked black stone for contrition, and red porphyry for Christ's blood sacrifice. With his sword, the angel marks each penitent's forehead with seven p's (from Latin peccatum, "sin") for the Seven Deadly Sins. When these wounds are washed away by penance, the soul may enter earthly paradise at the mountain's summit. Starry Heights In Paradiso, the third section of the Comedy, Dante visits the planets and constellations where blessed souls dwell. The celestial spheres look vague in this painting, but Dante had great interest in astronomy. One of his astronomical references still puzzles scholars. He notes "four stars, the same / The first men saw, and since, no living eye" (Purgatorio, I.23-24), apparently in reference to the Southern Cross. But that constellation was last visible at Dante's latitude (thanks to the earth's wobbly axis) in 3000 B.C., and no one else wrote about it in Europe until after Amerigo Vespucci's voyage in 1501. -

Jingles Barn 7 Hip No

Consigned by Eisaman Equine, Agent Hip No. Barn 900 Jingles 7 Gulch Thunder Gulch.................. Line of Thunder Invisible Ink ...................... Conquistador Cielo Jingles Conquistress..................... Bay Colt; Baby Elli March 4, 2008 Conquistador Cielo Marquetry ......................... Regent's Walk Countess Marq ................. (1998) Lear Fan Ah Love ............................ Colinear By INVISIBLE INK (1998). Black-type-placed winner of $465,088, 2nd Ken- tucky Derby [G1], etc. Sire of 5 crops of racing age, 90 foals, 57 starters, 33 winners of 74 races and earning $1,102,205, including champion Blessink (Clasico Dia de la Madre, etc.), and of Fearless Eagle ($274,175, Pete Axthelm S. [L] (CRC, $57,660), etc.), Twice a Princess ($141,323), Beckham Bend (to 4, 2009, $90,520), Keynes (to 4, 2009, $48,434), Out of Ink ($42,243), Disappearing Ink ($41,810), Invisible Jazz ($40,105). 1st dam Countess Marq, by Marquetry. 3 wins at 3 and 4, $102,735, 2nd Autumn Leaves H. [L] (MNR, $15,460). Dam of 4 other registered foals, 3 of rac- ing age, 3 to race, 2 winners-- Masala (c. by Lion Heart). Winner at 2 and 3, 2009, $110,388. Paniolo (c. by Invisible Ink). Winner at 2, 2009, $19,205. 2nd dam AH LOVE, by Lear Fan. Unraced. Dam of 5 winners, including-- DIAMONDS AND LEGS (f. by Quiet American). 3 wins at 2 and 3, $91,101, Laura Gal S. (LRL, $25,680), etc. Dam of 3 foals, 2 winners-- WILD GAMS (f. by Forest Wildcat). 9 wins, 2 to 5, $1,168,171, in N.A./U.S., Thoroughbred Club of America S. -

Each Round, Choose One of Three Scary* People from Our Collection to Love, Lust, Or Leave

A SCARY LOVE, LUST, LEAVE Each round, choose one of three scary* people from our collection to love, lust, or leave. Love: Good for the long-term. Bring them home to mom and raise a family ’til death do you part. Lust: This is your hit-it-and-quit-it option. It's great while it lasts, but forever isn’t necessary. Leave: The one you can’t stand the sight of. Kick them to the curb—you deserve better! * We're highlighting selected aspects of their traits and life for this game, but there is always more to the story! ROUND ONE Polynices He's the son of Oedipus (that guy who wanted to kill his dad and bed his mom). Because Polynices and his brother argued so much about who would take over Thebes when dad dies, Oedipus prayed to Zeus to curse them both to die by the other's hand, so the future was not very bright for this guy. FYI, he was “technically” married to the king of Argos’s daughter, who was given to him as a prize for winning a battle. As you do in ancient Greece. Jean-Nicolas Billaud-Varenne Though not one of the most well known figures from the French Revolution, Jean-Nicolas was instrumental in the Reign of Terror. He is considered one of the most violent anti-Royalists of the 18th century. He gave passionate speeches about kicking out all the foreigners living in France and employing the death penalty for unsuccessful French generals fighting for the country. -

Spring 2009 General Issue

Journal of the Short Story in English Les Cahiers de la nouvelle 52 | Spring 2009 General issue “Echo's Bones": Samuel Beckett's Lost Story of Afterlife José Francisco Fernández Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/jsse/962 ISSN: 1969-6108 Publisher Presses universitaires de Rennes Printed version Date of publication: 1 June 2009 ISSN: 0294-04442 Electronic reference José Francisco Fernández, « “Echo's Bones": Samuel Beckett's Lost Story of Afterlife », Journal of the Short Story in English [Online], 52 | Spring 2009, Online since 01 December 2010, connection on 03 December 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/jsse/962 This text was automatically generated on 3 December 2020. © All rights reserved “Echo's Bones": Samuel Beckett's Lost Story of Afterlife 1 “Echo's Bones": Samuel Beckett's Lost Story of Afterlife José Francisco Fernández 1 What until very recently was the terra incognita of Beckett studies, his early fiction of the 1930s, has been given a tremendous impulse in the last decade of the 20th century and in the first years of the 21st, thanks, among other things, to the publication in 1992 by Eoin O’Brien and Edith Fournier of Beckett’s first novel Dream of Fair to middling Women (written in 1932). Important scholarly works by John Pilling, such as Beckett before Godot (1997), have shed light on dark aspects of Beckett’s writing at this time, and naturally James Knowlson’s magnificient biography Damned to Fame (1996) has provided a reliable account of the author’s life during this obscure period. 2 Recent scholarship has put much emphasis on Beckett’s readings as a young man, in an attempt to trace the sources of his creative imagination (Beckett’s Books, 2006, by Matthew Feldman, and Notes Diverse Holo, 2006, edited by Matthijs Engelberts and Everett C.