CERN Accelerators

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CERN Courier–Digital Edition

CERNMarch/April 2021 cerncourier.com COURIERReporting on international high-energy physics WELCOME CERN Courier – digital edition Welcome to the digital edition of the March/April 2021 issue of CERN Courier. Hadron colliders have contributed to a golden era of discovery in high-energy physics, hosting experiments that have enabled physicists to unearth the cornerstones of the Standard Model. This success story began 50 years ago with CERN’s Intersecting Storage Rings (featured on the cover of this issue) and culminated in the Large Hadron Collider (p38) – which has spawned thousands of papers in its first 10 years of operations alone (p47). It also bodes well for a potential future circular collider at CERN operating at a centre-of-mass energy of at least 100 TeV, a feasibility study for which is now in full swing. Even hadron colliders have their limits, however. To explore possible new physics at the highest energy scales, physicists are mounting a series of experiments to search for very weakly interacting “slim” particles that arise from extensions in the Standard Model (p25). Also celebrating a golden anniversary this year is the Institute for Nuclear Research in Moscow (p33), while, elsewhere in this issue: quantum sensors HADRON COLLIDERS target gravitational waves (p10); X-rays go behind the scenes of supernova 50 years of discovery 1987A (p12); a high-performance computing collaboration forms to handle the big-physics data onslaught (p22); Steven Weinberg talks about his latest work (p51); and much more. To sign up to the new-issue alert, please visit: http://comms.iop.org/k/iop/cerncourier To subscribe to the magazine, please visit: https://cerncourier.com/p/about-cern-courier EDITOR: MATTHEW CHALMERS, CERN DIGITAL EDITION CREATED BY IOP PUBLISHING ATLAS spots rare Higgs decay Weinberg on effective field theory Hunting for WISPs CCMarApr21_Cover_v1.indd 1 12/02/2021 09:24 CERNCOURIER www. -

Proton Driven Plasma Wakefield Acceleration in AWAKE

Proton Driven Plasma Article submitted to journal Wakefield Acceleration in Subject Areas: AWAKE Plasma Wakefield Acceleration, 1 1 Proton Driven, Electron Acceleration E. Gschwendtner , M. Turner , **Author List Continues Next Page** Keywords: AWAKE, Plasma Wakefield Acceleration, Seeded Self Modulation In this article, we briefly summarize the experiments Author for correspondence: performed during the first Run of the Advanced Insert corresponding author name Wakefield Experiment, AWAKE, at CERN (European e-mail: [email protected] Organization for Nuclear Research). The final goal of AWAKE Run 1 (2013 - 2018) was to demonstrate that 10-20 MeV electrons can be accelerated to GeV- energies in a plasma wakefield driven by a highly- relativistic self-modulated proton bunch. We describe the experiment, outline the measurement concept and present first results. Last, we outline our plans for the future. 1 Continued Author List 2 E. Adli2,A. Ahuja1,O. Apsimon3;4,R. Apsimon3;4, A.-M. Bachmann1;5;6,F. Batsch1;5;6 C. Bracco1,F. Braunmüller5,S. Burger1,G. Burt7;4, B. Buttenschön8,A. Caldwell5,J. Chappell9, E. Chevallay1,M. Chung10,D. Cooke9,H. Damerau1, L.H. Deubner11,A. Dexter7;4,S. Doebert1, J. Farmer12, V.N. Fedosseev1,R. Fiorito13;4,R.A. Fonseca14,L. Garolfi1,S. Gessner1, B. Goddard1, I. Gorgisyan1,A.A. Gorn15;16,E. Granados1,O. Grulke8;17, A. Hartin9,A. Helm18, J.R. Henderson7;4,M. Hüther5, M. Ibison13;4,S. Jolly9,F. Keeble9,M.D. Kelisani1, S.-Y. Kim10, F. Kraus11,M. Krupa1, T. Lefevre1,Y. Li3;4,S. Liu19,N. Lopes18,K.V. Lotov15;16, M. Martyanov5, S. -

CERN to Seek Answers to Such Fundamental 1957, Was CERN’S First Accelerator

What is the nature of our universe? What is it ----------------------------------------- DAY 1 -------- made of? Scientists from around the world go to The 600 MeV Synchrocyclotron (SC), built in CERN to seek answers to such fundamental 1957, was CERN’s first accelerator. It provided questions using particle accelerators and pushing beams for CERN’s first experiments in particle and nuclear the limits of technology. physics. In 1964, this machine started to concentrate on nuclear physics alone, leaving particle physics to the newer During February 2019, I was given a once in a lifetime and more powerful Proton Synchrotron. opportunity to be part of The Maltese Teacher Programme at CERN, which introduced me, as one of the participants, to cutting-edge particle physics through lectures, on-site visits, exhibitions, and hands-on workshops. Why do they do all this? The main objective of these type of visits is to bring modern science into the classroom. Through this report, my purpose is to give an insight of what goes on at CERN as well as share my experience with you students, colleagues, as well as the general public. The SC became a remarkably long-lived machine. In 1967, it started supplying beams for a dedicated radioactive-ion-beam facility called ISOLDE, which still carries out research ranging from pure What does “CERN” stand for? At an nuclear physics to astrophysics and medical physics. In 1990, intergovernmental meeting of UNESCO in Paris in ISOLDE was transferred to the Proton Synchrotron Booster, and the SC closed down after 33 years of service. December 1951, the first resolution concerning the establishment of a European Council for Nuclear Research SM18 is CERN’s main facility for testing large and heavy (in French Conseil Européen pour la Recherche Nucléaire) superconducting magnets at liquid helium temperatures. -

The Large Hadron Collider Lyndon Evans CERN – European Organization for Nuclear Research, Geneva, Switzerland

34th SLAC Summer Institute On Particle Physics (SSI 2006), July 17-28, 2006 The Large Hadron Collider Lyndon Evans CERN – European Organization for Nuclear Research, Geneva, Switzerland 1. INTRODUCTION The Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at CERN is now in its final installation and commissioning phase. It is a two-ring superconducting proton-proton collider housed in the 27 km tunnel previously constructed for the Large Electron Positron collider (LEP). It is designed to provide proton-proton collisions with unprecedented luminosity (1034cm-2.s-1) and a centre-of-mass energy of 14 TeV for the study of rare events such as the production of the Higgs particle if it exists. In order to reach the required energy in the existing tunnel, the dipoles must operate at 1.9 K in superfluid helium. In addition to p-p operation, the LHC will be able to collide heavy nuclei (Pb-Pb) with a centre-of-mass energy of 1150 TeV (2.76 TeV/u and 7 TeV per charge). By modifying the existing obsolete antiproton ring (LEAR) into an ion accumulator (LEIR) in which electron cooling is applied, the luminosity can reach 1027cm-2.s-1. The LHC presents many innovative features and a number of challenges which push the art of safely manipulating intense proton beams to extreme limits. The beams are injected into the LHC from the existing Super Proton Synchrotron (SPS) at an energy of 450 GeV. After the two rings are filled, the machine is ramped to its nominal energy of 7 TeV over about 28 minutes. In order to reach this energy, the dipole field must reach the unprecedented level for accelerator magnets of 8.3 T. -

Il Nostro Mondo

IL NOSTRO MONDO THE DESIGN, CONSTRUCTION AND PERFORMANCE OF THE CERN INTERSECTING STORAGE RINGS (ISR) A RECOLLECTION OF WORLD’S FIRST PROTON-PROTON COLLIDER KURT HÜBNER CERN, Geneva, Switzerland 1 Design which had a beam energy of 160 MeV. The interaction points to increase the collision rate The concept of colliding beams appeared design of these colliders started in 1957. but without special lattice insertions as one first in a German patent by Rolf Widerøe In 1961, the Accelerator Research Group would use these days. registered in 1943 and published in 1952. Division was expanded into the Accelerator Combined-function magnets were chosen However, at that time the intensity of beams Division as experienced manpower had as in the PS, i.e. the main magnets had a was too low for an exploitable collision rate as become available after the running-in of the magnetic dipole field to bend the beam and a beam accumulation had not yet been invented. PS in 1960. At the same time it was decided quadrupole field to focus the beam. This type The first ideas of a realistic design were to construct a small accelerator to test rf of magnet provided space for the elaborate published in 1956 by Gerard O’Neill and by the stacking, a technique to be experimentally pole-face windings foreseen to control the MURA Group lead by Donald Kerst in the USA. proven, as it was essential for the performance magnetic field to a very high precision. It also MURA had come up with beam accumulation and success of the ISR. -

Beam–Material Interactions

Beam–Material Interactions N.V. Mokhov1 and F. Cerutti2 1Fermilab, Batavia, IL 60510, USA 2CERN, Geneva, Switzerland Abstract This paper is motivated by the growing importance of better understanding of the phenomena and consequences of high-intensity energetic particle beam interactions with accelerator, generic target, and detector components. It reviews the principal physical processes of fast-particle interactions with matter, effects in materials under irradiation, materials response, related to component lifetime and performance, simulation techniques, and methods of mitigating the impact of radiation on the components and environment in challenging current and future applications. Keywords Particle physics simulation; material irradiation effects; accelerator design. 1 Introduction The next generation of medium- and high-energy accelerators for megawatt proton, electron, and heavy- ion beams moves us into a completely new domain of extreme energy deposition density up to 0.1 MJ/g and power density up to 1 TW/g in beam interactions with matter [1, 2]. The consequences of controlled and uncontrolled impacts of such high-intensity beams on components of accelerators, beamlines, target stations, beam collimators and absorbers, detectors, shielding, and the environment can range from minor to catastrophic. Challenges also arise from the increasing complexity of accelerators and experimental set-ups, as well as from design, engineering, and performance constraints. All these factors put unprecedented requirements on the accuracy of particle production predictions, the capability and reliability of the codes used in planning new accelerator facilities and experiments, the design of machine, target, and collimation systems, new materials and technologies, detectors, and radiation shielding and the minimization of radiation impact on the environment. -

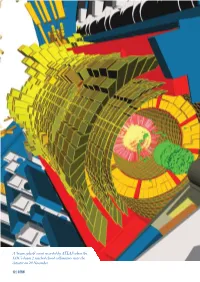

Event Recorded by ATLAS When the LHC's Beam 2 Reached Closed

A ‘beam splash’ event recorded by ATLAS when the LHC’s beam 2 reached closed collimators near the detector on 20 November. 12 | CERN “The imminent start-up of the LHC is an event that excites everyone who has an interest in the fundamental physics of the Universe.” Kaname Ikeda, ITER Director-General, CERN Bulletin, 19 October 2009. Physics and Experiments The moment that particle physicists around the world had been The EMCal is an upgrade for ALICE, having received full waiting for finally arrived on 20 November 2009 when protons approval and construction funds only in early 2008. It will detect circulated again round the LHC. Over the following days, the high-energy photons and neutral pions, as well as the neutral machine passed a number of milestones, from the first collisions component of ‘jets’ of particles as they emerge from quark� at 450 GeV per beam to collisions at a total energy of 2.36 TeV gluon plasma formed in collisions between heavy ions; most — a world record. At the same time, the LHC experiments importantly, it will provide the means to select these events on began to collect data, allowing the collaborations to calibrate line. The EMCal is basically a matrix of scintillator and lead, detectors and assess their performance prior to the real attack which is contained in ‘supermodules’ that weigh about eight tonnes. It will consist of ten full supermodules and two partial on high-energy physics in 2010. supermodules. The repairs to the LHC and subsequent consolidation work For the ATLAS Collaboration, crucial repair work included following the incident in September 2008 took approximately modifications to the cooling system for the inner detector. -

CERN Intersecting Storage Rings (ISR)

Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 70, No. 2, pp. 619-626, February 1973 CERN Intersecting Storage Rings (ISR) K. JOHNSEN CERN It has been realized for many years that it would be possible to beams of protons collide with sufficiently high interaction obtain a glimpse into a much higher energy region for ele- rates for feasible experimentation in an energy range otherwise mentary-particle research if particle beams could be persuaded unattainable by known techniques except at enormous cost. to collide head-on. A group at CERN started investigating this possibility in To explain why this is so, let us consider what happens in a 1957, first studying a special two-way fixed-field alternating conventional accelerator experiment. When accelerated gradient (FFAG) accelerator and then, in 1960, turning to the particles have reached the required energy they are directed idea of two intersecting storage rings that could be fed by the onto a target and collide with the stationary particles of the CERN 28 GeV proton synchrotron (CERN-PS). This change target. Most of the energy given to the accelerated particles in concept for these initial studies was stimulated by the then goes into keeping the particles that result from the promising performance of the CERN-PS from the very start collision moving in the direction of the incident particles (to of its operation in 1959. conserve momentum). Only a quite modest fraction is "useful After an extensive study that included building an electron energy" for the real purpose of the experiment-the trans- storage ring (CESAR) to investigate many of the associated formation of particles, the creation of new particles. -

Femtoscopy of Proton-Proton Collisions in the ALICE Experiment

Femtoscopy of proton-proton collisions in the ALICE experiment DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Nicolas Bock, B.Sc. B.Eng., M.Sc. Graduate Program in Physics The Ohio State University 2011 Dissertation Committee: Professor Thomas J. Humanic, Advisor Professor Michael Lisa #1 Professor Klaus Honscheid #2 Professor Richard Furnstahl #3 c Copyright by Nicolas Bock 2011 Abstract The Large Ion Collider Experiment (ALICE) at CERN has been designed to study matter at extreme conditions of temperature and pressure, with the long term goal of observing deconfined matter (free quarks and gluons), study its properties and learn more details about the phase diagram of nuclear matter. The ALICE experiment provides excellent particle tracking capabilities in high multiplicity proton-proton and heavy ion collisions, allowing to carry out detailed research of nuclear matter. This dissertation presents the study of the space time structure of the particle emission region, also known as femtoscopy, in proton- proton collisions at 0.9, 2.76 and 7.0 TeV. The emission region can be characterized by taking advantage of the Bose-Einstein effect for identical particles, which causes an enhancement of produced identical pairs at low relative momentum. The geometry of the emission region is related to the relative momentum distribution of all pairs by the Fourier transform of the source function, therefore the measurement of the final relative momentum distribution allows to extract the initial space-time characteristics. Results show that there is a clear dependence of the femtoscopic radii on event multiplicity as well as transverse momentum, a signature of the transition of nuclear matter into its fundamental components and also of strong interaction among these. -

Pos(ICRC2019)446

New Results from the Cosmic-Ray Program of the NA61/SHINE facility at the CERN SPS PoS(ICRC2019)446 Michael Unger∗ for the NA61/SHINE Collaborationy Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT), Postfach 3640, D-76021 Karlsruhe, Germany E-mail: [email protected] The NA61/SHINE experiment at the SPS accelerator at CERN is a unique facility for the study of hadronic interactions at fixed target energies. The data collected with NA61/SHINE is relevant for a broad range of topics in cosmic-ray physics including ultrahigh-energy air showers and the production of secondary nuclei and anti-particles in the Galaxy. Here we present an update of the measurement of the momentum spectra of anti-protons produced in p−+C interactions at 158 and 350 GeV=c and discuss their relevance for the understanding of muons in air showers initiated by ultrahigh-energy cosmic rays. Furthermore, we report the first results from a three-day pilot run aimed at investigating the ca- pability of our experiment to measure nuclear fragmentation cross sections for the understanding of the propagation of cosmic rays in the Galaxy. We present a preliminary measurement of the production cross section of Boron in C+p interactions at 13.5 AGeV=c and discuss prospects for future data taking to provide the comprehensive and accurate reaction database of nuclear frag- mentation needed in the era of high-precision measurements of Galactic cosmic rays. 36th International Cosmic Ray Conference -ICRC2019- July 24th - August 1st, 2019 Madison, WI, U.S.A. ∗Speaker. yhttp://shine.web.cern.ch/content/author-list c Copyright owned by the author(s) under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). -

NA61/SHINE Facility at the CERN SPS: Beams and Detector System

Preprint typeset in JINST style - HYPER VERSION NA61/SHINE facility at the CERN SPS: beams and detector system N. Abgrall11, O. Andreeva16, A. Aduszkiewicz23, Y. Ali6, T. Anticic26, N. Antoniou1, B. Baatar7, F. Bay27, A. Blondel11, J. Blumer13, M. Bogomilov19, M. Bogusz24, A. Bravar11, J. Brzychczyk6, S. A. Bunyatov7, P. Christakoglou1, T. Czopowicz24, N. Davis1, S. Debieux11, H. Dembinski13, F. Diakonos1, S. Di Luise27, W. Dominik23, T. Drozhzhova20 J. Dumarchez18, K. Dynowski24, R. Engel13, I. Efthymiopoulos10, A. Ereditato4, A. Fabich10, G. A. Feofilov20, Z. Fodor5, A. Fulop5, M. Ga´zdzicki9;15, M. Golubeva16, K. Grebieszkow24, A. Grzeszczuk14, F. Guber16, A. Haesler11, T. Hasegawa21, M. Hierholzer4, R. Idczak25, S. Igolkin20, A. Ivashkin16, D. Jokovic2, K. Kadija26, A. Kapoyannis1, E. Kaptur14, D. Kielczewska23, M. Kirejczyk23, J. Kisiel14, T. Kiss5, S. Kleinfelder12, T. Kobayashi21, V. I. Kolesnikov7, D. Kolev19, V. P. Kondratiev20, A. Korzenev11, P. Koversarski25, S. Kowalski14, A. Krasnoperov7, A. Kurepin16, D. Larsen6, A. Laszlo5, V. V. Lyubushkin7, M. Mackowiak-Pawłowska´ 9, Z. Majka6, B. Maksiak24, A. I. Malakhov7, D. Maletic2, D. Manglunki10, D. Manic2, A. Marchionni27, A. Marcinek6, V. Marin16, K. Marton5, H.-J.Mathes13, T. Matulewicz23, V. Matveev7;16, G. L. Melkumov7, M. Messina4, St. Mrówczynski´ 15, S. Murphy11, T. Nakadaira21, M. Nirkko4, K. Nishikawa21, T. Palczewski22, G. Palla5, A. D. Panagiotou1, T. Paul17, W. Peryt24;∗, O. Petukhov16 C.Pistillo4 R. Płaneta6, J. Pluta24, B. A. Popov7;18, M. Posiadala23, S. Puławski14, J. Puzovic2, W. Rauch8, M. Ravonel11, A. Redij4, R. Renfordt9, E. Richter-Wa¸s6, A. Robert18, D. Röhrich3, E. Rondio22, B. Rossi4, M. Roth13, A. Rubbia27, A. Rustamov9, M. -

Fifty Years of the CERN Proton Synchrotron Volume II

CERN–2013–005 12 August 2013 ORGANISATION EUROPÉENNE POUR LA RECHERCHE NUCLÉAIRE CERN EUROPEAN ORGANIZATION FOR NUCLEAR RESEARCH Fifty years of the CERN Proton Synchrotron Volume II Editors: S. Gilardoni D. Manglunki GENEVA 2013 ISBN 978–92–9083–391–8 ISSN 0007–8328 DOI 10.5170/CERN–2013–005 Copyright c CERN, 2013 Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Knowledge transfer is an integral part of CERN’s mission. CERN publishes this report Open Access under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/) in order to permit its wide dissemination and use. This monograph should be cited as: Fifty years of the CERN Proton Synchrotron, volume II edited by S. Gilardoni and D. Manglunki, CERN-2013-005 (CERN, Geneva, 2013), DOI: 10.5170/CERN–2013–005 Dedication The editors would like to express their gratitude to Dieter Möhl, who passed away during the preparatory phase of this volume. This report is dedicated to him and to all the colleagues who, like him, contributed in the past with their cleverness, ingenuity, dedication and passion to the design and development of the CERN accelerators. iii Abstract This report sums up in two volumes the first 50 years of operation of the CERN Proton Synchrotron. After an introduction on the genesis of the machine, and a description of its magnet and powering systems, the first volume focuses on some of the many innovations in accelerator physics and instrumentation that it has pioneered, such as transition crossing, RF gymnastics, extractions, phase space tomography, or transverse emittance measurement by wire scanners.