6 X 10.Three Lines .P65

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Conditions of Dramatic Production to the Death of Aeschylus Hammond, N G L Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies; Winter 1972; 13, 4; Proquest Pg

The Conditions of Dramatic Production to the Death of Aeschylus Hammond, N G L Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies; Winter 1972; 13, 4; ProQuest pg. 387 The Conditions of Dramatic Production to the Death of Aeschylus N. G. L. Hammond TUDENTS of ancient history sometimes fall into the error of read Sing their history backwards. They assume that the features of a fully developed institution were already there in its earliest form. Something similar seems to have happened recently in the study of the early Attic theatre. Thus T. B. L. Webster introduces his excellent list of monuments illustrating tragedy and satyr-play with the following sentences: "Nothing, except the remains of the old Dionysos temple, helps us to envisage the earliest tragic background. The references to the plays of Aeschylus are to the lines of the Loeb edition. I am most grateful to G. S. Kirk, H. D. F. Kitto, D. W. Lucas, F. H. Sandbach, B. A. Sparkes and Homer Thompson for their criticisms, which have contributed greatly to the final form of this article. The students of the Classical Society at Bristol produce a Greek play each year, and on one occasion they combined with the boys of Bristol Grammar School and the Cathedral School to produce Aeschylus' Oresteia; they have made me think about the problems of staging. The following abbreviations are used: AAG: The Athenian Agora, a Guide to the Excavation and Museum! (Athens 1962). ARNon, Conventions: P. D. Arnott, Greek Scenic Conventions in the Fifth Century B.C. (Oxford 1962). BIEBER, History: M. Bieber, The History of the Greek and Roman Theatre2 (Princeton 1961). -

The Hyporcheme of Pratinas

The Classical Review http://journals.cambridge.org/CAR Additional services for The Classical Review: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here The Hyporcheme of Pratinas H. W. Garrod The Classical Review / Volume 34 / Issue 7-8 / November 1920, pp 129 - 136 DOI: 10.1017/S0009840X00014013, Published online: 27 October 2009 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0009840X00014013 How to cite this article: H. W. Garrod (1920). The Hyporcheme of Pratinas. The Classical Review, 34, pp 129-136 doi:10.1017/S0009840X00014013 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/CAR, IP address: 193.61.135.80 on 07 Apr 2015 The Classical Review NOVEMBER—DECEMBER, 1920 ORIGINAL CONTRIBUTIONS THE HYPORCHEME OF PRATINAS. ATHE.VAEUS 617b, 8 : Upanva<; Se o strangely to our ears—of ' Pindar and <£>\tao-jo5, avXrjTcov Kal yppevrSyv Karexov- Dionysius of Thebes and Lamprus and TCOV ras opxfiaTpas, ayava/CTeiv Tivas eVt Pratinas and the other lyrists who ex- ra> Tou? av\r]Ta$ fir) ffvvavXeiv T019 celled in musical composition (irot,7)T(n Kaddirep r)v Trdrpiov, aK~Ka i j(pp Kpov/jLarav ayaOoi,),' (1146 B). He asso- %vvaheiv rots avK-qrals. ov o?iv elye dvfibv ciates Pratinas always with the theory Kara rwv ravra TTOIOVVTWV o of music and with the hyporcheme ifi<f>avL£ei Bia TOOOV rov v (1133, 1142,1134: cf. Plut. Symp. IX. 2). TIS 6 Obpvfios 85e ; ri rdSe ra ^opei^ara ; Of the Pratinas who has chiefly in- TIS ijflpis 1/ioXev eirl AiovvcriaSa TroXvirdraya Ov/j.4- terested modern scholarship, the \ ; Pratinas who wrote tragic and satyric tfiis ifids 0 Bp6/uos • i/U 5ei KfXadeiv, Se? dramas, the Pratinas who contended for iraTayetv, av' 6pea ai^evov /terd Nal'dSaw, fame with Aeschylus, he knows nothing. -

Athenaeus' Reading of the Aulos Revolution ( Deipnosophistae 14.616E–617F)

The Journal of Hellenic Studies http://journals.cambridge.org/JHS Additional services for The Journal of Hellenic Studies: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here New music and its myths: Athenaeus' reading of the Aulos revolution ( Deipnosophistae 14.616e–617f) Pauline A. Leven The Journal of Hellenic Studies / Volume 130 / November 2010, pp 35 - 48 DOI: 10.1017/S0075426910000030, Published online: 19 November 2010 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0075426910000030 How to cite this article: Pauline A. Leven (2010). New music and its myths: Athenaeus' reading of the Aulos revolution ( Deipnosophistae 14.616e– 617f). The Journal of Hellenic Studies, 130, pp 35-48 doi:10.1017/S0075426910000030 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/JHS, IP address: 147.91.1.45 on 23 Sep 2013 Journal of Hellenic Studies 130 (2010) 35−47 DOI: 10.1017/S0075426910000030 NEW MUSIC AND ITS MYTHS: ATHENAEUS’ READING OF THE AULOS REVOLUTION (DEIPNOSOPHISTAE 14.616E−617F) PAULINE A. LEVEN Yale University* Abstract: Scholarship on the late fifth-century BC New Music Revolution has mostly relied on the evidence provided by Athenaeus, the pseudo-Plutarch De musica and a few other late sources. To this date, however, very little has been done to understand Athenaeus’ own role in shaping our understanding of the musical culture of that period. This article argues that the historical context provided by Athenaeus in the section of the Deipnosophistae that cites passages of Melanippides, Telestes and Pratinas on the mythology of the aulos (14.616e−617f) is not a credible reflection of the contemporary aesthetics and strategies of the authors and their works. -

Music, Ritual, and Self-Referentiality in the Second Stasimon of Euripides’ Helen the Dionysian Necessity

Greek and Roman Musical Studies 6 (2018) 247-264 brill.com/grms Music, Ritual, and Self-Referentiality in the Second Stasimon of Euripides’ Helen The Dionysian Necessity Barbara Castiglioni Università di Torino [email protected]/[email protected] Abstract The imagery of Dionysiac performance is characteristic of Euripides’ later choral odes and returns particularly in the Helen’s second stasimon, which foregrounds its own connections with the mimetic program of the New Music and its emphasis on the emancipation of feelings. This paper aims to show that Euripides’ deep interest in con- temporary musical innovations is connected to his interest in the irrational, which made him the most tragic of the poets. Focusing on the musical aspect of the Helen’s second stasimon, the paper will examine how Euripides conveys a sense of the irratio- nal through a new type of song, which liberates music’s power to excite and disorient through its colors, ornament and dizzying wildness. Just as the New Musicians pres- ent themselves as the preservers of cultic tradition, Euripides, far from suppressing Dionysus as Nietzsche claimed, deserves to rank as the most Dionysiac and the most religious of the three tragedians. Keywords Euripides – tragedy – New Music – Dionysus – religion – choral self-referentiality Introduction The choral odes of tragedy regularly involve the Chorus reflecting upon an ear- lier moment in the play or its related myths. In Euripides’ Helen, all three sta- sima are distanced from the action by their mood. The first choral ode follows © koninklijke brill nv, leiden, 2018 | doi:10.1163/22129758-12341322Downloaded from Brill.com09/23/2021 09:44:20AM via free access 248 Castiglioni the successful persuasion of the prophetess, Theonoe, the working out of a good escape plan and high optimism on the part of Helen and Menelaus, but seems to ignore the progress of the play’s action and takes the audience back to the ruin caused by the Trojan war. -

Greek Tragedy Themes and Contexts 1St Edition Ebook, Epub

GREEK TRAGEDY THEMES AND CONTEXTS 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Laura Swift | 9781474236836 | | | | | Greek Tragedy Themes and Contexts 1st edition PDF Book For help and support relating to the University's computing resources:. After dialogue based interactions were eventually brought into development, the percentage of scripts read by the chorus tended to decrease in regards to their involvement in the play. Get A Copy. Refresh and try again. For a small book it packs a hefty punch, with a clear and engaging style that should be accessible to a wide audience. The philosopher also asserted that the action of epic poetry and tragedy differ in length, "because in tragedy every effort is made for it to take place in one revolution of the sun, while the epic is unlimited in time. Another novelty of Euripidean drama is represented by the realism with which the playwright portrays his characters' psychological dynamics. The Greek chorus of up to 50 men and boys danced and sang in a circle, probably accompanied by an aulos , relating to some event in the life of Dionysus. As elsewhere in the book, the chapter kicks off with contextual information, this time on the prevalence of choruses in ancient Greek life, and proceeds to a discussion of their tragic manifestation. After a brief analysis of the genre and main figures, it focuses on the broader questions of what defines tragedy, what its particular preoccupations are, and what makes these texts so widely studied and performed more than 2, years after they were written. Visit the Australia site. The theatre voiced ideas and problems from the democratic, political and cultural life of Athens. -

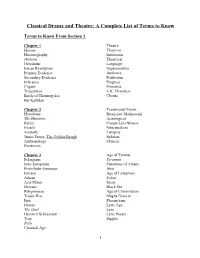

A Complete List of Terms to Know

Classical Drama and Theatre: A Complete List of Terms to Know Terms to Know From Section 1: Chapter 1 Theatre History Theatron Historiography Institution Historia Theatrical Herodotus Language Ionian Revolution Impersonation Primary Evidence Audience Secondary Evidence Positivism Inference Progress Cogent Primitive Tripartition E.K. Chambers Battle of Thermopylae Chorus Ibn Kahldun Chapter 2 Transitional Forms Herodotus Bronislaw Malinowski The Histories Aetiological Relics Claude Levi-Strauss Fossils Structuralism Aristotle Lumpers James Frazer, The Golden Bough Splitters Anthropology Mimetic Positivism Chapter 3 Age of Tyrants Pelasgians Tyrannos Indo-Europeans Pisistratus of Athens Proto-Indo-European Attic Ionians Age of Lawgivers Athens Solon Asia Minor Sicily Dorians Black Sea Peloponnese Age of Colonization Trojan War Magna Graecia Epic Phoenicians Homer Lyric Age The Iliad Lyre Heinrich Schliemann Lyric Poetry Troy Sappho Polis Classical Age 1 Chapter 4.1 City Dionysia Thespis Ecstasy Tragoidia "Nothing To Do With Dionysus" Aristotle Year-Spirit The Poetics William Ridgeway Dithyramb Tomb-Theory Bacchylides Hero-Cult Theory Trialogue Gerald Else Dionysus Chapter 4.2 Niches Paleontologists Fitness Charles Darwin Nautilus/Nautiloids Transitional Forms Cultural Darwinism Gradualism Pisistratus Steven Jay Gould City Dionysia Punctuated Equilibrium Annual Trading Season Terms to Know From Section 2: Chapter 5 Sparta Pisistratus Peloponnesian War Athens Post-Classical Age Classical Age Macedon(ia) Persian Wars Barbarian Pericles Philip -

Aus: Zeitschrift Für Papyrologie Und Epigraphik 118 (1997) 174–178

PETER J. WILSON AMYMON OF SIKYON: A FIRST VICTORY IN ATHENS AND A FIRST TRAGIC KHOREGIC DEDICATION IN THE CITY? (SEG 23, 103B) aus: Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 118 (1997) 174–178 © Dr. Rudolf Habelt GmbH, Bonn 174 AMYMON OF SIKYON: A FIRST VICTORY IN ATHENS AND A FIRST TRAGIC KHOREGIC DEDICATION IN THE CITY? (SEG 23, 103B)* In the third decade of the fourth century, a man from the Attic deme of Pallene (his name lost) was a victorious khoregos at the Great Panathenaia (probably that of 375/4 or 370/69). His khoros was one of boys dancing the pyrrhikhe for Athene. He commemorated the occasion with a monument which carried an account of the victory in formulaic terms familiar from comparable inscriptions; and which had a delicate relief of part at least of the victorious khoros carved on the same surface, underneath and divid- ing the letters of the inscription.1 Although the find-spot of this monument is not known, a Panathenaic dedication such as this seems certain to derive from an urban setting, very probably – like a number of similar cases – from the Akropolis.2 To this monument a second victory-inscription was added, probably soon after the first was cut (since the letter-forms are the same), but certainly after the design of the monument had been conceived. It was put on the right-hand side of the stone, not on its principal front face. The right-hand edge of this side of the stone is roughly broken, and allows for no certain calculation of its original width. -

Problems of Early Greek Tragedy: Pratinas, Phrynichus, the Gyges Fragment

PROBLEMS OF EARLY GREEK TRAGEDY: PRATINAS, PHRYNICHUS, THE GYGES FRAGMENT by Hugh Lloyd-Jones No chapter in the history of Greek Uterature is more obs- cure than the origins of tragedy, and indeed its whole history before the second quarter of the fifth century. The beginnings are veiled in darkness; even the statement of Aristotle that tragedy originated from the dithyramb is not universally accep- ted; and those who do accept it disagree about the nature of the early dithyramb and its influence on tragedy. Recent ac• cessions to our knowledge have only made this darkness dar• ker. Till 1952 it was widely believed that we possessed a play written by Aeschylus early in his career, perhaps as early as about 500 B. C, when he was some twenty-five years old. In that year the publication of a scrap of papyrus ^ put paid to that delusion. We must now recognise that the Suppliants of Aeschylus was in all probability produced in 464 or 463, and is therefore later than the Persians, produced in 472, and the Seven Against Thebes, produced in 467. For the century and a half between the date given for the first performance of Thespis at the Dionysia and that of the production of the Per^ sians, we have no specimen of a tragedy. » P. Oxy. 2256, fr. 3. published as £r. 288 in SMYTH-LLOYD-JO- NES, Aeschylus, II, London, 1957 (Loeb CI. Libr.), 595-598, with dis• cussion and bibliography; see also LLOYD-JONES, The "Supplices" of Aeschylus: The New Date and Old Problems (Ant. -

The Power of Music

THE POWER OF MUSIC A comparative study of literature and vase paintings from Classical Athens University of Uppsala Department of Archaeology and Ancient History Master’s Thesis 45 points Louisa Sakka Spring 2009 Supervisor: Gullög Nordquist ii ABSTRACT Louisa Sakka, 2009, The power of music. A comparative study of literature and vase paintings from Classical Athens . Master’s thesis. Department of Archaeology and Ancient History, University of Uppsala. This paper deals with ancient Greek music, and in particular the relation of people to music during the fifth century BC in Athens. Music is believed to exercise great power over the human character and behavior, and at the same time is a means of emotional communication. For the first time during the fifth century, the power of music leaves the realm of the myths and becomes a subject of philosophical investigation. Two different types of sources are examined in order to study the relation of people to music: on the one hand the literary sources of this period, and on the other the vase paintings. This method reveals various attitudes towards music by using two different perspectives. Possible explanations are given for the differing information, the purpose of each source being a decisive factor. The paper suggests that although the information from the two types of sources varies and can even be contradictive, the recognition of the power music exercises is obvious in both cases. Keywords: music, ethos, power, Plato, vase paintings, art, Athens, Classical, literature, New Music. Louisa Sakka, Department of Archaeology and Ancient History, University of Uppsala. Sweden. iii iv In memory of my father v vi TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. -

Metatheatricality in the Greek Satyr-Play 35

ARCTOS ACTA PHILOLOGICA FENNICA VOL. XXXV HELSINKI 2001 INDEX NEIL ADKIN "I Am Tedious Aeneas": Virgil, Aen. 1,372 ff. 9 JEAN-PIERRE GUILHEMBET Quelques domus ou résidences romaines négligées 15 RIIKKA HÄLIKKÄ Sparsis comis, solutis capillis: 'Loose' Hair in Ovid's 23 Elegiac Poetry MAARIT KAIMIO ET ALII Metatheatricality in the Greek Satyr-Play 35 MIKA KAJAVA Hanging Around Downtown 79 KALLE KORHONEN Osservazioni sul collezionismo epigrafico siciliano 85 PETER KRUSCHWITZ Zwei sprachliche Beobachtungen zu republikanischen 103 Rechtstexten UTA-MARIA LIERTZ Die Dendrophoren aus Nida und Kaiserverehrung von 115 Kultvereinen im Nordwesten des Imperium Romanum LUIGI PEDRONI Il significato dei segni di valore sui denarii repubbli- 129 cani: contributi per la riapertura di una problematica OLLI SALOMIES Roman Nomina in the Greek East: Observations on 139 Some Recently Published Inscriptions WERNER J. SCHNEIDER Ein der Heimat verwiesener Autor: Anaximenes von 175 Lampsakos bei Lukian, Herod. 3 HEIKKI SOLIN Analecta epigraphica CXCII–CXCVIII 189 De novis libris iudicia 243 Index librorum in hoc volumine recensorum 298 Libri nobis missi 300 Index scriptorum 303 METATHEATRICALITY IN THE GREEK SATYR-PLAY MAARIT KAIMIO ET ALII* In a famous fragment of Pratinas, described as a hyporchema by Athenaeus (4 F 3, Athen. 14,617b), a chorus of satyrs pours a torrent of indignation on the increasing role of the music of aulos in a choral performance. The exact target of their hostility, the literary genre of the poem and the identity of the Pratinas in question are under scholarly debate.1 One argument for the view that the fragment cannot be from a satyr-play, let alone from an early one, has been the metatheatrical theme of the song: open discussion among the performers of the suitability of their music to the context of performance. -

Should There Have Been a Polis in Aristotle's Poetics? Classical Quarterly, 59 (2)

promoting access to White Rose research papers Universities of Leeds, Sheffield and York http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/43155/ Published paper: Heath, MF (2009) Should there have been a polis in Aristotle's Poetics? Classical Quarterly, 59 (2). 468 - 485. White Rose Research Online [email protected] Classical Quarterly 59.2 468–485 (2009) Printed in Great Britain 468 doi:10.1017/S0009838809990115 SHOULD THERE HAVE BEEN APOLIS IN ARISTOTLE’SMALCOLMPOETICS HEATH? SHOULD THERE HAVE BEEN A POLIS IN ARISTOTLE’S POETICS? In her contribution to the collection Tragedy and the Tragic, Edith Hall asks ‘is there a polis in Aristotle’s Poetics?’1 She concludes that there is not, and sees the absence as in need of explanation. It is certainly strikingly at variance with a prominent emphasis in much recent scholarship on tragedy;2 but Hall also notes that awareness of a relationship between tragedy and its social context is in evidence in other fifth- and fourth-century sources, including other works by Aristotle. Hall’s explanation of Aristotle’s approach in the Poetics looks to his personal status, as an outsider in Athens, and historical moment, at a time when tragedy was ‘about’ to be internation- alized; Aristotle’s deliberate divorce of poetry and the polis, she suggests, caught an emergent tendency (304–5). Hall’s question is prompted by Aristotle’s apparent failure to attend to a topic of dominant interest to classicists with an orientation to cultural and social history. The terms of her answer reflect the same dominant interests. -

Choruses for Dionysus: Studies in the History of Dithyramb and Tragedy by Matthew C. Wellenbach B.A., Williams College, 2009

Choruses for Dionysus: Studies in the History of Dithyramb and Tragedy By Matthew C. Wellenbach B.A., Williams College, 2009 Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Classics at Brown University PROVIDENCE, RHODE ISLAND MAY 2015 © Copyright 2015 by Matthew C. Wellenbach This dissertation by Matthew C. Wellenbach is accepted in its present form by the Department of Classics as satisfying the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Date________________ _______________________________________ Johanna Hanink, Advisor Recommended to the Graduate Council Date________________ _______________________________________ Deborah Boedeker, Reader Date_______________ _______________________________________ Pura Nieto Hernández, Reader Date_______________ _______________________________________ Andrew Ford, Reader Approved by the Graduate Council Date_______________ _______________________________________ Peter M. Weber, Dean of the Graduate School iii Curriculum Vitae Matthew C. Wellenbach was born on June 4, 1987, in Philadelphia, PA. He first began studying Latin during his primary and second education, and in 2009 he earned a B.A. in Classics, magna cum laude, and with highest honors, from Williams College, located in Williamstown, MA. In the fall of 2008, he was inducted into Phi Beta Kappa. He matriculated at Brown University in Providence, RI, in the fall of 2009 as a graduate student in the Department of Classics. During his time at Brown, he presented a paper on similes in the Odyssey at the 2012 meeting of the Classical Association of the Middle West and South and published a review of a monograph on Aeschylus’ Suppliant Women in Bryn Mawr Classical Review as well as an article on depictions of choral performance in Attic vase-paintings in Greek Roman and Byzantine Studies.