Greek Tragedy Themes and Contexts 1St Edition Ebook, Epub

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Conditions of Dramatic Production to the Death of Aeschylus Hammond, N G L Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies; Winter 1972; 13, 4; Proquest Pg

The Conditions of Dramatic Production to the Death of Aeschylus Hammond, N G L Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies; Winter 1972; 13, 4; ProQuest pg. 387 The Conditions of Dramatic Production to the Death of Aeschylus N. G. L. Hammond TUDENTS of ancient history sometimes fall into the error of read Sing their history backwards. They assume that the features of a fully developed institution were already there in its earliest form. Something similar seems to have happened recently in the study of the early Attic theatre. Thus T. B. L. Webster introduces his excellent list of monuments illustrating tragedy and satyr-play with the following sentences: "Nothing, except the remains of the old Dionysos temple, helps us to envisage the earliest tragic background. The references to the plays of Aeschylus are to the lines of the Loeb edition. I am most grateful to G. S. Kirk, H. D. F. Kitto, D. W. Lucas, F. H. Sandbach, B. A. Sparkes and Homer Thompson for their criticisms, which have contributed greatly to the final form of this article. The students of the Classical Society at Bristol produce a Greek play each year, and on one occasion they combined with the boys of Bristol Grammar School and the Cathedral School to produce Aeschylus' Oresteia; they have made me think about the problems of staging. The following abbreviations are used: AAG: The Athenian Agora, a Guide to the Excavation and Museum! (Athens 1962). ARNon, Conventions: P. D. Arnott, Greek Scenic Conventions in the Fifth Century B.C. (Oxford 1962). BIEBER, History: M. Bieber, The History of the Greek and Roman Theatre2 (Princeton 1961). -

Tragedy, Euripides, Melodrama: Hamartia, Medea, Liminality

Vol. 5 (2013) | pp. 143-171 http://dx.doi.org/10.5209/rev_AMAL.2013.v5.42932 TRAGEDY, EURIPIDES, MELODRAMA: HAMARTIA, MEDEA, LIMINALITY BRIAN G. CARAHER QUEEN’S UNIVERSITY BELFAST, NORTHERN IRELAND [email protected] Article received on 29.01.2013 Accepted on 06.07.2013 ABSTRACT This article examines socio-historical dimensions and cultural and dramaturgic implications of the Greek playwright Euripides’ treatment of the myth of Medea. Euripides gives voice to victims of adventurism, aggression and betrayal in the name of ‘reason’ and the ‘state’ or ‘polity.’ Medea constitutes one of the most powerful mythic forces to which he gave such voice by melodramatizing the disturbing liminality of Greek tragedy’s perceived social and cultural order. The social polity is confronted by an apocalyptic shock to its order and its available modes of emotional, rational and social interpretation. Euripidean melodramas of horror dramatize the violation of rational categories and precipitate an abject liminality of the tragic vision of rational order. The dramaturgy of Euripides’ Medea is contrasted with the norms of Greek tragedy and examined in comparison with other adaptations — both ancient and contemporary — of the myth of Medea, in order to unfold the play’s transgression of a tragic vision of the social polity. KEYWORDS Dramaturgy, Euripides, liminality, Medea, melodrama, preternatural powers, social polity, tragedy. TRAGEDIA, EURÍPIDES, MELODRAMA: HAMARTÍA, MEDEA, LIMINALIDAD RESUMEN Este artículo estudia las dimensiones sociohistóricas y las implicaciones culturales y teatrales del tratamiento que Eurípides da al mito de Medea. Eurípides da voz a las víctimas del aventurerismo, de las agresiones y de las traiciones cometidas en nombre de la ‘razón’ y del ‘estado’ o el ‘gobierno’. -

The Hyporcheme of Pratinas

The Classical Review http://journals.cambridge.org/CAR Additional services for The Classical Review: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here The Hyporcheme of Pratinas H. W. Garrod The Classical Review / Volume 34 / Issue 7-8 / November 1920, pp 129 - 136 DOI: 10.1017/S0009840X00014013, Published online: 27 October 2009 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0009840X00014013 How to cite this article: H. W. Garrod (1920). The Hyporcheme of Pratinas. The Classical Review, 34, pp 129-136 doi:10.1017/S0009840X00014013 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/CAR, IP address: 193.61.135.80 on 07 Apr 2015 The Classical Review NOVEMBER—DECEMBER, 1920 ORIGINAL CONTRIBUTIONS THE HYPORCHEME OF PRATINAS. ATHE.VAEUS 617b, 8 : Upanva<; Se o strangely to our ears—of ' Pindar and <£>\tao-jo5, avXrjTcov Kal yppevrSyv Karexov- Dionysius of Thebes and Lamprus and TCOV ras opxfiaTpas, ayava/CTeiv Tivas eVt Pratinas and the other lyrists who ex- ra> Tou? av\r]Ta$ fir) ffvvavXeiv T019 celled in musical composition (irot,7)T(n Kaddirep r)v Trdrpiov, aK~Ka i j(pp Kpov/jLarav ayaOoi,),' (1146 B). He asso- %vvaheiv rots avK-qrals. ov o?iv elye dvfibv ciates Pratinas always with the theory Kara rwv ravra TTOIOVVTWV o of music and with the hyporcheme ifi<f>avL£ei Bia TOOOV rov v (1133, 1142,1134: cf. Plut. Symp. IX. 2). TIS 6 Obpvfios 85e ; ri rdSe ra ^opei^ara ; Of the Pratinas who has chiefly in- TIS ijflpis 1/ioXev eirl AiovvcriaSa TroXvirdraya Ov/j.4- terested modern scholarship, the \ ; Pratinas who wrote tragic and satyric tfiis ifids 0 Bp6/uos • i/U 5ei KfXadeiv, Se? dramas, the Pratinas who contended for iraTayetv, av' 6pea ai^evov /terd Nal'dSaw, fame with Aeschylus, he knows nothing. -

The Structure of Plays

n the previous chapters, you explored activities preparing you to inter- I pret and develop a role from a playwright’s script. You used imagina- tion, concentration, observation, sensory recall, and movement to become aware of your personal resources. You used vocal exercises to prepare your voice for creative vocal expression. Improvisation and characterization activities provided opportunities for you to explore simple character portrayal and plot development. All of these activities were preparatory techniques for acting. Now you are ready to bring a character from the written page to the stage. The Structure of Plays LESSON OBJECTIVES ◆ Understand the dramatic structure of a play. 1 ◆ Recognize several types of plays. ◆ Understand how a play is organized. Much of an actor’s time is spent working from materials written by playwrights. You have probably read plays in your language arts classes. Thus, you probably already know that a play is a story written in dia- s a class, play a short logue form to be acted out by actors before a live audience as if it were A game of charades. Use the titles of plays and musicals or real life. the names of famous actors. Other forms of literature, such as short stories and novels, are writ- ten in prose form and are not intended to be acted out. Poetry also dif- fers from plays in that poetry is arranged in lines and verses and is not written to be performed. ■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■ These students are bringing literature to life in much the same way that Aristotle first described drama over 2,000 years ago. -

Greek Theory of Tragedy: Aristotle's Poetics

Greek Theory of Tragedy: Aristotle's Poetics The classic discussion of Greek tragedy is Aristotle's Poetics. He defines tragedy as "the imitation of an action that is serious and also as having magnitude, complete in itself." He continues, "Tragedy is a form of drama exciting the emotions of pity and fear. Its action should be single and complete, presenting a reversal of fortune, involving persons renowned and of superior attainments, and it should be written in poetry embellished with every kind of artistic expression." The writer presents "incidents arousing pity and fear, wherewith to interpret its catharsis of such of such emotions" (by catharsis, Aristotle means a purging or sweeping away of the pity and fear aroused by the tragic action). The basic difference Aristotle draws between tragedy and other genres, such as comedy and the epic, is the "tragic pleasure of pity and fear" the audience feel watching a tragedy. In order for the tragic hero to arouse these feelings in the audience, he cannot be either all good or all evil but must be someone the audience can identify with; however, if he is superior in some way(s), the tragic pleasure is intensified. His disastrous end results from a mistaken action, which in turn arises from a tragic flaw or from a tragic error in judgment. Often the tragic flaw is hubris, an excessive pride that causes the hero to ignore a divine warning or to break a moral law. It has been suggested that because the tragic hero's suffering is greater than his offense, the audience feels pity; because the audience members perceive that they could behave similarly, they feel pity. -

Athenaeus' Reading of the Aulos Revolution ( Deipnosophistae 14.616E–617F)

The Journal of Hellenic Studies http://journals.cambridge.org/JHS Additional services for The Journal of Hellenic Studies: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here New music and its myths: Athenaeus' reading of the Aulos revolution ( Deipnosophistae 14.616e–617f) Pauline A. Leven The Journal of Hellenic Studies / Volume 130 / November 2010, pp 35 - 48 DOI: 10.1017/S0075426910000030, Published online: 19 November 2010 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0075426910000030 How to cite this article: Pauline A. Leven (2010). New music and its myths: Athenaeus' reading of the Aulos revolution ( Deipnosophistae 14.616e– 617f). The Journal of Hellenic Studies, 130, pp 35-48 doi:10.1017/S0075426910000030 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/JHS, IP address: 147.91.1.45 on 23 Sep 2013 Journal of Hellenic Studies 130 (2010) 35−47 DOI: 10.1017/S0075426910000030 NEW MUSIC AND ITS MYTHS: ATHENAEUS’ READING OF THE AULOS REVOLUTION (DEIPNOSOPHISTAE 14.616E−617F) PAULINE A. LEVEN Yale University* Abstract: Scholarship on the late fifth-century BC New Music Revolution has mostly relied on the evidence provided by Athenaeus, the pseudo-Plutarch De musica and a few other late sources. To this date, however, very little has been done to understand Athenaeus’ own role in shaping our understanding of the musical culture of that period. This article argues that the historical context provided by Athenaeus in the section of the Deipnosophistae that cites passages of Melanippides, Telestes and Pratinas on the mythology of the aulos (14.616e−617f) is not a credible reflection of the contemporary aesthetics and strategies of the authors and their works. -

Music, Ritual, and Self-Referentiality in the Second Stasimon of Euripides’ Helen the Dionysian Necessity

Greek and Roman Musical Studies 6 (2018) 247-264 brill.com/grms Music, Ritual, and Self-Referentiality in the Second Stasimon of Euripides’ Helen The Dionysian Necessity Barbara Castiglioni Università di Torino [email protected]/[email protected] Abstract The imagery of Dionysiac performance is characteristic of Euripides’ later choral odes and returns particularly in the Helen’s second stasimon, which foregrounds its own connections with the mimetic program of the New Music and its emphasis on the emancipation of feelings. This paper aims to show that Euripides’ deep interest in con- temporary musical innovations is connected to his interest in the irrational, which made him the most tragic of the poets. Focusing on the musical aspect of the Helen’s second stasimon, the paper will examine how Euripides conveys a sense of the irratio- nal through a new type of song, which liberates music’s power to excite and disorient through its colors, ornament and dizzying wildness. Just as the New Musicians pres- ent themselves as the preservers of cultic tradition, Euripides, far from suppressing Dionysus as Nietzsche claimed, deserves to rank as the most Dionysiac and the most religious of the three tragedians. Keywords Euripides – tragedy – New Music – Dionysus – religion – choral self-referentiality Introduction The choral odes of tragedy regularly involve the Chorus reflecting upon an ear- lier moment in the play or its related myths. In Euripides’ Helen, all three sta- sima are distanced from the action by their mood. The first choral ode follows © koninklijke brill nv, leiden, 2018 | doi:10.1163/22129758-12341322Downloaded from Brill.com09/23/2021 09:44:20AM via free access 248 Castiglioni the successful persuasion of the prophetess, Theonoe, the working out of a good escape plan and high optimism on the part of Helen and Menelaus, but seems to ignore the progress of the play’s action and takes the audience back to the ruin caused by the Trojan war. -

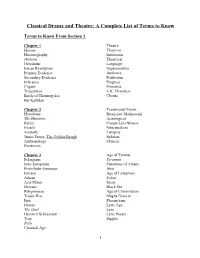

A Complete List of Terms to Know

Classical Drama and Theatre: A Complete List of Terms to Know Terms to Know From Section 1: Chapter 1 Theatre History Theatron Historiography Institution Historia Theatrical Herodotus Language Ionian Revolution Impersonation Primary Evidence Audience Secondary Evidence Positivism Inference Progress Cogent Primitive Tripartition E.K. Chambers Battle of Thermopylae Chorus Ibn Kahldun Chapter 2 Transitional Forms Herodotus Bronislaw Malinowski The Histories Aetiological Relics Claude Levi-Strauss Fossils Structuralism Aristotle Lumpers James Frazer, The Golden Bough Splitters Anthropology Mimetic Positivism Chapter 3 Age of Tyrants Pelasgians Tyrannos Indo-Europeans Pisistratus of Athens Proto-Indo-European Attic Ionians Age of Lawgivers Athens Solon Asia Minor Sicily Dorians Black Sea Peloponnese Age of Colonization Trojan War Magna Graecia Epic Phoenicians Homer Lyric Age The Iliad Lyre Heinrich Schliemann Lyric Poetry Troy Sappho Polis Classical Age 1 Chapter 4.1 City Dionysia Thespis Ecstasy Tragoidia "Nothing To Do With Dionysus" Aristotle Year-Spirit The Poetics William Ridgeway Dithyramb Tomb-Theory Bacchylides Hero-Cult Theory Trialogue Gerald Else Dionysus Chapter 4.2 Niches Paleontologists Fitness Charles Darwin Nautilus/Nautiloids Transitional Forms Cultural Darwinism Gradualism Pisistratus Steven Jay Gould City Dionysia Punctuated Equilibrium Annual Trading Season Terms to Know From Section 2: Chapter 5 Sparta Pisistratus Peloponnesian War Athens Post-Classical Age Classical Age Macedon(ia) Persian Wars Barbarian Pericles Philip -

History of Greek Theatre

HISTORY OF GREEK THEATRE Several hundred years before the birth of Christ, a theatre flourished, which to you and I would seem strange, but, had it not been for this Grecian Theatre, we would not have our tradition-rich, living theatre today. The ancient Greek theatre marks the First Golden Age of Theatre. GREEK AMPHITHEATRE- carved from a hillside, and seating thousands, it faced a circle, called orchestra (acting area) marked out on the ground. In the center of the circle was an altar (thymele), on which a ritualistic goat was sacrificed (tragos- where the word tragedy comes from), signifying the start of the Dionysian festival. - across the circle from the audience was a changing house called a skene. From this comes our present day term, scene. This skene can also be used to represent a temple or home of a ruler. (sometime in the middle of the 5th century BC) DIONYSIAN FESTIVAL- (named after Dionysis, god of wine and fertility) This festival, held in the Spring, was a procession of singers and musicians performing a combination of worship and musical revue inside the circle. **Women were not allowed to act. Men played these parts wearing masks. **There was also no set scenery. A- In time, the tradition was refined as poets and other Greek states composed plays recounting the deeds of the gods or heroes. B- As the form and content of the drama became more elaborate, so did the physical theatre itself. 1- The skene grow in size- actors could change costumes and robes to assume new roles or indicate a change in the same character’s mood. -

Three Different Jocastas by Racine, Cocteau and Cixous

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2010 Three Different Jocastas By Racine, Cocteau And Cixous Kyung Mee Joo University of Central Florida Part of the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Joo, Kyung Mee, "Three Different Jocastas By Racine, Cocteau And Cixous" (2010). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 1623. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/1623 THREE DIFFERENT JOCASTAS BY RACINE, COCTEAU, AND CIXOUS by KYUNG MEE JOO A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Theatre in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Fall Term 2010 Major Professor: Julia Listengarten ©2010 Kyung Mee Joo ii ABSTRACT This study is about three French plays in which Jocasta, the mother and wife of Oedipus, is shared as a main character: La Thébaïde (The Theban Brothers) by Jean Racine, La Machine Infernale (The Infernal Machine) by Jean Cocteau, and Le Nom d’Oedipe (The Name of Oedipus) by Hélène Cixous. Jocasta has always been overshadowed by the tragic destiny of Oedipus since the onset of Sophocles’ works. Although these three plays commonly focus on describing the character of Jocasta, there are some remarkable differences among them in terms of theme, style, and stage directions. -

Protecting the American Playwright John Weidman

Brooklyn Law Review Volume 72 | Issue 2 Article 5 2007 THE SEVENTH ANNUAL MEDIA & SOCIETY LECTURE: Protecting the American Playwright John Weidman Follow this and additional works at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/blr Recommended Citation John Weidman, THE SEVENTH ANNUAL MEDIA & SOCIETY LECTURE: Protecting the American Playwright, 72 Brook. L. Rev. (2007). Available at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/blr/vol72/iss2/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at BrooklynWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Brooklyn Law Review by an authorized editor of BrooklynWorks. THE SEVENTH ANNUAL MEDIA AND SOCIETY LECTURE Protecting the American Playwright John Weidman† I want to begin by clarifying something which is going to become stunningly clear whether I clarify it now or not. I am not an attorney. I did in fact graduate from law school. I did in fact take and pass the New York Bar Exam. But to give you a sense of how long ago that was, when I finished the exam I celebrated by picking up a six pack of Heineken and going home to watch the Watergate Hearings. I have never practiced law. But as President of the Dramatists Guild of America for the last eight years I have found myself in the middle of a number of legal collisions, the most important of which I’m going to talk about today, not from a lawyer’s perspective—although I may attempt to dazzle you with a couple of actual citations—but from the perspective of the playwrights, composers, and lyricists whose interests the Guild represents. -

Download Thesis

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ Ancient Greek folksong tradition begging, work, and ritual song Genova, Antonio Awarding institution: King's College London The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT Unless another licence is stated on the immediately following page this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 26. Sep. 2021 Ancient Greek Folksong Tradition Begging, Work, and Ritual Song by Antonio Genova A Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Classics King’s College London November 2018 Abstract This dissertation investigates whether and in what sense the concept of folksong can be applied to the ancient Greek texts.