Facebook-Only Social Journalism Yomna

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Music for a New Day Artist Bio

Music for a New Day Artist bio Fariba Davody: Fariba Davody is a musician, vocalist, and teacher who first captured public eye performing classical Persian songs in Iran, and donating her proceeds from her show. She performed a lot of concerts and festivals such as the concert in Agha khan museum in 2016 in Toronto , concerts with Kiya Tabassian in Halifax and Montreal, and Tirgan festival in 2017, 2018, 2019, and 2021 in Toronto. Fariba opened a Canadian branch of Avaye Mehr music and art school where she continues to teach. Raphael Weinroth-Browne: Canadian cellist and composer Raphael Weinroth- Browne has forged a uniQue career and international reputation as a result of his musical creativity and versatility. Not confined to a single genre or project, his musical activities encompass a multitude of styles and combine influences from contemporary classical, Middle Eastern, and progressive metal music. His groundbreaking duo, The Visit, has played major festivals such as Wave Gotik Treffen (Germany), 21C (Canada), and the Cello Biennale Amsterdam (Netherlands). As one half of East-meets-West ensemble Kamancello, he composed “Convergence Suite,” a double concerto which the duo performed with the Windsor Symphony Orchestra to a sold out audience. Raphael's cello is featured prominently on the latest two albums from Norwegian progressive metal band Leprous; he has played over 150 shows with them in Europe, North America, and the Middle East. Raphael has played on over 100 studio albums including the Juno Award-winning Woods 5: Grey Skies & Electric Light (Woods of Ypres) and Juno-nominated UpfRONt (Ron Davis’ SymphRONica) - both of which feature his own compositions/arrangements - as well as the Juno-nominated Ayre Live (Miriam Khalil & Against The Grain Ensemble). -

The Interaction Between Citizen Media and the Mainstream Media Media Organisation in Egypt During 2011, 2012 & 2013

BIRMINGHAM CITY UNIVERSITY The Interaction Between Citizen Media and the Mainstream Media Media Organisation in Egypt during 2011, 2012 & 2013 77,000 Words Noha Atef Supervisors: Prof. Tim Wall Dr. Dima Saber Submitted to the Faculty of Art, Design and Media at Birmingham City University in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy I declare that this is a true copy of the examined manuscript of my PhD thesis in 17th January, 2017, which was further submitted on 10th March, 2017 with minor changes approved by the examiners. 1 Abstract THE INTERACTION BETWEEN CITIZEN MEDIA AND THE MAINSTREAM MEDIA Media Organisation of Egypt during 2011, 2012 & 2013 This research explores the mutual influences between citizen media and the mainstream media, through studying two phenomena occurred in Egypt during the years 2011, 2012 and 2013; which are the institutionalisation of citizen journalism and the employment of a number of citizen journalists in the mainstream media. The thesis answers the question: What is the nature of interaction between citizen media and the mainstream media? I argue that the citizen media -mainstream media interaction is driven by the medium, which is the social media, the media organizer; or the individuals who control the media outlet, either by having editorial authority, such as Editors-in-chief, or owning it. In addition, the mass media are another driver of the interaction between citizen media and the mainstream media. Plus, the relationship between the citizens of the state and the political regime too, it influence the convergence and divergence of citizen media and the mainstream media. -

Citizen Journalists and Mass Self-Communication in Egypt

Citizen Journalists and Mass Self-Communication in Egypt The Use of New Media as Counter Power During the Egyptian Revolution Author MSc Thesis Adriëtte Sneep 860502 780020 International Development Studies Supervisors Dr. R. Lie Communication Sciences Dr. Ir. O. Hospes Public Administration and Policy Group Wageningen University February 2013 Wageningen University – Department of Social Sciences Law and Governance Group February 2013 Citizen Journalists and Mass Self-Communication in Egypt The Use of New Media as Counter Power During the Egyptian Revolution Thesis submitted to the Law and Governance Group in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Master of Science degree in International Development Studies Adriëtte Sneep Registration Number: 860502 780020 Course Code: LAW-80433 Supervised by Dr. R. Lie Communication Sciences Dr. Ir. O. Hospes Public Administration and Policy Group ii iii Abstract During the first months of 2011 mass demonstrations in the Arab world was front page news. In January and February 2011 Egyptians demonstrated 18 days and ultimately Mubarak was forced to resign. Revolutions happened before, so there is really nothing new under the sun, but what was remarkable about the reporting on the demonstrations was the attention for new media, such as Facebook and Twitter, which was predominantly used by young people during the demonstrations. Some people even called it a Facebook revolution, which illustrates the importance of new media during the Egyptian revolution. Since revolutions happened before Facebook was invented, this thesis explores the role of new media during the Egyptian revolution. This research aims to find out how people used it, what type of new media they used, when and how they felt about this. -

Social Media and Egypt's Arab Spring

Social Media and Egypt’s Arab Spring Lieutenant-Commander G.W. Bunghardt JCSP 40 PCEMI 40 Exercise Solo Flight Exercice Solo Flight Disclaimer Avertissement Opinions expressed remain those of the author and do Les opinons exprimées n’engagent que leurs auteurs et not represent Department of National Defence or ne reflètent aucunement des politiques du Ministère de Canadian Forces policy. This paper may not be used la Défense nationale ou des Forces canadiennes. Ce without written permission. papier ne peut être reproduit sans autorisation écrite. © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, as represented by the © Sa Majesté la Reine du Chef du Canada, représentée par le Minister of National Defence, 2014. ministre de la Défense nationale, 2014. CANADIAN FORCES COLLEGE / COLLÈGE DES FORCES CANADIENNES JCSP 40 / PCEMI 40 Social Media and Egypt’s Arab Spring By LCdr G.W. Bunghardt This paper was written by a student attending La présente étude a été rédigée par un the Canadian Forces College in fulfilment of stagiaire du Collège des Forces canadiennes one of the requirements of the Course of pour satisfaire à l'une des exigences du cours. Studies. The paper is a scholastic document, L'étude est un document qui se rapporte au and thus contains facts and opinions, which the cours et contient donc des faits et des opinions author alone considered appropriate and que seul l'auteur considère appropriés et correct for the subject. It does not necessarily convenables au sujet. Elle ne reflète pas reflect the policy or the opinion of any agency, nécessairement la politique ou l'opinion d'un including the Government of Canada and the organisme quelconque, y compris le Canadian Department of National Defence. -

Who Has a Voice in Egypt?

#Sisi_vs_Youth: Who Has a Voice in Egypt? ALBRECHT HOFHEINZ (University of Oslo) Abstract This article presents voices from Egypt reflecting on the question of who has the right to have a voice in the country in the first half of 2016. In the spirit of the research project “In 2016,” it aims to offer a snapshot of how it “felt to live” in Egypt in 2016 as a member of the young generation (al-shabāb) who actively use social media and who position themselves critically towards the state’s official discourse. While the state propagated a strategy focusing on educating and guiding young people towards becoming productive members of a nation united under one leader, popular youth voices on the internet used music and satire to claim their right to resist a retrograde patrimonial system that threatens every opposing voice with extinc- tion. On both sides, a strongly antagonistic ‘you vs. us’ rhetoric is evident. 2016: “The Year of Egyptian Youth” (Sisi style) January 9, 2016 was celebrated in Egypt as Youth Day—a tradition with only a brief histo- ry. The first Egyptian Youth Day had been marked on February 9, 2009; the date being chosen by participants in the Second Egyptian Youth Conference in commemoration of the martyrs of the famous 1946 student demonstrations that eventually led to the resignation of then Prime Minister Nuqrāshī. Observed in 2009 and 2010 with only low-key events, the carnivalesque “18 days” of revolutionary unrest in January-February 2011 interrupted what Rather than a conventional academic paper, this article aims to be a miniature snapshot of how it ‘felt’ to live in Egypt by mid-2016 as a member of the young generation (al-shabāb) who have access to so- cial media (ca. -

Vanderbilt University

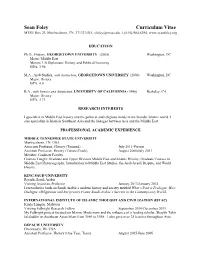

Sean Foley Curriculum Vitae MTSU Box 23, Murfreesboro, TN, 37132 USA, [email protected], 1-(615)-904-8294, www.seanfoley.org EDUCATION Ph.D., History, GEORGETOWN UNIVERSITY (2005) Washington, DC Major: Middle East Minors: US Diplomatic History and Political Economy GPA: 3.96 M.A., Arab Studies, with distinction, GEORGETOWN UNIVERSITY (2000) Washington, DC Major: History GPA: 4.0 B.A., with honors and distinction, UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA (1996) Berkeley, CA Major: History GPA: 3.73 RESEARCH INTERESTS I specialize in Middle East history and the political and religious trends in the broader Islamic world. I also specialize in Islam in Southeast Asia and the linkages between Asia and the Middle East. PROFESSIONAL ACADEMIC EXPERIENCE MIDDLE TENNESSEE STATE UNIVERSITY Murfreesboro, TN USA Associate Professor, History (Tenured) July 2011-Present Assistant Professor, History (Tenure-Track) August 2006-July 2011 Member, Graduate Faculty Courses Taught: Graduate and Upper Division Middle East and Islamic History, Graduate Courses in Middle East Historiography, Introduction to Middle East Studies, the Arab-Israeli Dispute, and World History. KING SAUD UNIVERSITY Riyadh, Saudi Arabia Visiting Associate Professor January 2013-January 2014 I researched a book on Saudi Arabia’s modern history and society entitled What’s Past is Prologue: How Dialogue, Obligations and Reciprocity Frame Saudi Arabia’s Success in the Contemporary World. INTERNATIONAL INSTITUTE OF ISLAMIC THOUGHT AND CIVILIZATION (ISTAC) Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia Visiting Fulbright Research Fellow September 2010-December 2011 My Fulbright project focused on Islamic Modernism and the influence of a leading scholar, Shaykh Tahir Jalaluddin on Southeast Asian Islam from 1869 to 1958. I also gave over 25 lectures throughout Asia. -

A Sociolinguistic Study of Code Choice Among Saudis on Twitter

A Sociolinguistic Study of Code Choice among Saudis on Twitter by Saeed Ali Al Alaslaa A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Near Eastern Studies) in The University of Michigan 2018 Doctoral Committee: Professor Mohammad T. Alhawary, Chair Associate Professor Abdulkafi Albirini, Utah State University Professor Marlyse N. Baptista Professor Emeritus Raji M. Rammuny Saeed A. Al Alaslaa [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0002-0527-2334 © Saeed A. Al Alaslaa 2018 ACKNOWLEDGMENT First and foremost, all praise is to the Almighty God for His grace and blessings throughout my entire life. Second, I would like to express my sincere gratitude and deep appreciation to my dissertation committee members for their constructive feedback and the time they dedicated to reading and offering suggestions on the writing of my dissertation. In addition, I want to convey my endless thanks to my advisor, Professor Mohammad Alhawary, who has expanded my knowledge of Arabic linguistics on both levels, theoretical and applied. The Arabic theoretical linguistics classes that I have taken with him were immensely beneficial, including Arabic syntax, semantics, phonology, morphology, historical linguistics, and dialectology. From the applied linguistics perspective, I really benefited from the courses he taught me, such as Arabic second language acquisition, Arabic teaching methodology, as well as the independent classes through which my research topic and interests have evolved and thrived. I am indebted to him for his outstanding direction, guidance, support, patience, and generosity with his time and advice. I hold in the highest esteem everything he has done for me. -

Egypt: News Websites and DEFENDING FREEDOM of EXPRESSION and INFORMATION Alternative Voices

Fulleer Egypt: News websites and DEFENDING FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION AND INFORMATION alternative voices ARTICLE 19 Free Word Centre 60 Farringdon Road London EC1R 3GA T: +44 20 7324 2500 F: +44 20 7490 0566 E: [email protected] W: www.article19.org 2014 Tw: @article19org Fb: facebook.com/article19org © ARTICLE 19 ARTICLE 19 Free Word Centre 60 Farringdon Road London EC1R 3GA United Kingdom T: +44 20 7324 2500 F: +44 20 7490 0566 E: [email protected] W: www.article19.org Tw: @article19org Fb: facebook.com/article19org ISBN: 978-1-906586-98-0 © ARTICLE 19, 2014 This report is a joint publication between ARTICLE 19: Global Campaign for Free Expression and the Heliopolis Institute in Cairo. The interviews and drafting of the report were carried out by Mohamed El Dahshan and Rayna Stamboliyska from the Heliopolis Institute. Staff from the ARTICLE 19 MENA Programme contributed desk-research and edited the final draft. It was reviewed by the Director of Programmes of ARTICLE 19 and the Senior Legal Officer of ARTICLE 19. The report’s design was coordinated by the Communications Officer of ARTICLE 19. This work is provided under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-ShareAlike 2.5 licence. You are free to copy, distribute and display this work and to make derivative works, except for the images which are specifically licensed from other organisations, provided you: 1. give credit to ARTICLE 19 2. do not use this work for commercial purposes 3. distribute any works derived from this publication under a licence identical to this one. To access the full legal text of this licence, please visit: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc-sa/2.5/legalcode. -

Egypt 2013 Human Rights Report

EGYPT 2013 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Egypt is a republic governed at year’s end by interim President Adly Mansour, appointed by the armed forces on July 3 following the removal of President Mohamed Morsy and his government the same day. The government derives its authority from the July 3 announcement by Minister of Defense Abdel Fattah al-Sisi and the July 8 Constitutional Declaration issued by interim President Mansour. The Constitutional Declaration vested the interim president with legislative authority until a new legislature is elected, which was expected in the first half of 2014. Elections, both parliamentary and presidential, were scheduled to follow a January 2014 referendum on a new draft constitution that was completed on December 6. The authorities at times failed to maintain effective control over the security forces. Security forces committed human rights abuses. After antigovernment protests throughout the spring, which culminated in massive demonstrations against the government in Cairo and other governorates on June 30, President Morsy and his government were ousted, and security forces detained Morsy at an undisclosed location. The military suspended the 2012 constitution, and six weeks of confrontations between security forces and demonstrators opposed to Morsy’s removal followed. On August 14, Ministry of Interior forces supported by military units used lethal force to disperse large Muslim Brotherhood (MB)-organized sit-ins at Rabaa al-Adawiya Square in Cairo and Nahda Square in Giza. According to the Forensic Medicine Authority, 398 persons died during these operations, and a total of 726 protesters were killed nationwide between August 14 and November 13. -

Exploring the Postrevolutionary Digital Public Sphere in Egypt

International Journal of Communication 14(2020), 491–513 1932–8036/20200005 Disaffection, Anger, and Sarcasm: Exploring the Postrevolutionary Digital Public Sphere in Egypt EUGENIA SIAPERA MAY ALAA ABDEL MOHTY University College Dublin, Ireland This article explores the digital public sphere in Egypt through a 3-pronged investigation. First, we examine the media sphere from an institutional point of view. Second, we undertake a qualitative analysis of comments left on popular news pages on Facebook. Third, we discuss the findings of 30 semistructured interviews with young people in Cairo. Our results indicate that the media system is characterized by increasing control that has now extended online, whereas the social media space is dominated by religious personalities and entertainment. Turning to the public, we found that most comments mobilized anger and insults or were ironic and sarcastic. Finally, the interviews point to a disillusionment with both the political sphere and the role of social media. Disaffection is therefore taken to represent the specific structure of feeling found in the postrevolutionary Egyptian mainstream digital public sphere, with publics appearing alienated and unwilling to engage politically. Keywords: digital public sphere, Egypt, social media, hybrid media system, hypermedia space, affective publics The historical events of January 2011 in Egypt were pivotal in leading to a broader rethinking of the Arab world, its media, and its public sphere. However, recent developments have been contentious. The rise of the Muslim Brotherhood has been meteoric, and its fall swift: After being voted in as the first democratically elected president of Egypt in 2012, Mohammed Morsi’s short and controversial presidency ended a year later, in 2013, after a series of protests and the intervention of the army. -

THIS ISSUE THIS ● Sector to Yemen'sfuture ● Ocean Acidification Khettara: a Traditionalyetviable Irrigationoption

Volume 13 - Number 2 February – March 2017 £4 THIS ISSUE: Environment ● West Asia and the Global Environment Outlook ● Ocean acidification● The political ecology of virtual water in Palestine ● The main challenge to Yemen's future ● The challenges of integrating off-grid electricity in Oman's domestic sector ● Sustainable energy planning in MENA ● The evolution of the Nile regulatory regime ● Khettara: a traditional yet viable irrigation option ● PLUS Events in London Volume 13 - Number 2 February – March 2017 £4 THIS ISSUE: Environment ● West Asia and the Global Environment Outlook ● Ocean acidification● The political ecology of virtual water in Palestine ● The main challenge to Yemen's future ● Can Oman’s domestic electricity go off-grid? ● Sustainable energy planning in MENA ● The evolution of the Nile regulatory regime ● Khettara : a traditional yet viable irrigation option ● PLUS Events in London Ibrahim El Dessouki, m3, salteries, 2006. Courtesy of About the London Middle East Institute (LMEI) Bibliotheca Alexandrina The London Middle East Institute (LMEI) draws upon the resources of London and SOAS to provide teaching, training, research, publication, consultancy, outreach and other services related to the Middle Volume 13 – Number 2 East. It serves as a neutral forum for Middle East studies broadly defined and helps to create links between individuals and institutions with academic, commercial, diplomatic, media or other specialisations. February – March 2017 With its own professional staff of Middle East experts, the LMEI is further strengthened by its academic membership – the largest concentration of Middle East expertise in any institution in Europe. The LMEI also has access to the SOAS Library, which houses over 150,000 volumes dealing with all aspects of the Middle Editorial Board East. -

The Use of Facebook As a Source of News in Post-Revolutionary Egypt

The American University in Cairo School of Global Affairs and Public Policy The Use of Facebook as a Source of News in Post-Revolutionary Egypt A Thesis Submitted to The Department of Journalism and Mass Communication in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts by Sondos Asem under the supervision of Dr. Mohamad Elmasry May 2013 1 ABSTRACT Social media, particularly Facebook, played a key role in the 2011 Egyptian revolution. Facebook was not only used to put forth the first call for revolution, but it also gave Egypt's youth a safe and user-friendly venue for exchanging political views, engaging in heated political debates, and obtaining up-to-date news from "citizen journalists"—namely, amateur reporters and Facebook users who posted status updates, pictures, videos, and notes concerning current events and breaking news. This research project investigates the use of Facebook as a news outlet for Egyptian youth in the 18 months following the revolution. The current study seeks to explore whether Facebook is becoming an alternative source of information for Egyptian internet users in replacement of traditional news media. It employs survey research as a primary method to answer the proposed research questions via a purposive sample of 360 Egyptian internet users. The findings of the survey – which support both the literature review and theories of uses and gratifications of online media – suggest a significant displacement effect of social media on the usage of traditional media. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................... 7 2. LITERATURE REVIEW ............................................................... 25 2.1. History and Evolution of Social Media: ...........................................