Vietnam Summary Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

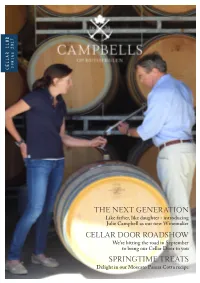

The Next Generation

spring 2017 CELLAR CLUB THE NEXT GENERATION Like father, like daughter - introducing Julie Campbell as our new Winemaker CELLAR DOOR ROADSHOW We’re hitting the road in September to bring our Cellar Door to you SPRINGTIME TREATS Delight in our Moscato Panna Cotta recipe e’ve got a spring in our step Was we look forward to more exciting times at Campbells and Merchant Prince Muscat were extremely well received by both the public and panelists alike, which goes to show just how impressive Australian wine really is to the rest of the world. More on that on page 8. Back at home, the whole team was busy with our winter events calendar which included Winery Walkabout, our Campbells Wine Dinners and Game of Rhones. I particularly enjoyed representing Campbells at the Melbourne Game of Rhones event, which celebrated the great grape varieties of the Rhone Valley. Think Grenache, Shiraz, Mourvedre and more from some of the best wine producers in the country. But our events for the year don’t end there! We’ve got our Cellar Door Roadshows coming up, as well as our inaugural spring dinner. Read more about what we have in store on page 5. As for news in the licensedFlashback trade to Vintage sector, 2016... I’ve been very busy hostingSusie many ‘working’ retailer the ferment! tasting events around the state and beyond. It’s great to be able to chat to customers about our wines and see exactly why they choose to buy Campbells, time and time again. As you can see, spring is shaping up to be a ere we are again approaching spring very busy time for us at Campbells, and we Hand it feels like only yesterday that the hope yours is as lively and festive as ours! vineyard team were in the throes of Vintage 2017. -

VAASAN AMMATTIKORKEAKOULU UNIVERSITY of APPLIED SCIENCES Tourism and Restaurant Management

Nga Nguyen FINNISH CUSTOMERS’BEVERAGE CHOICE AND THE POTENTIAL OF VI- ETNAMESE WINE IN FINLAND Case: Vaasa citizens‘ beverage choices in Asian restaurant ii Business Economics and Tourism 2014 ii VAASAN AMMATTIKORKEAKOULU UNIVERSITY OF APPLIED SCIENCES Tourism and Restaurant Management ABSTRACT Author Nga Thi Bich Nguyen Title Finnish customers’ beverage choices and the potential of Vietnamese wine in Finland Year 2015 Language English Pages 42 + 2 Appendixes Name of Supervisor Helena Alamäki The aim of the thesis is to discover the potential of selling Asian wine and bever- ages in Vaasa in particular and in Finland in general. The Asian wine means all of the alcohol made locally Asian with different ingredients including fruit, rice and grapes. The thesis primarily concentrated on the combination of Asian food along with wine in different theory. From that, it gives the outlook of pairing Asian food with local Asian beverages. It presents general information about Asian food and in addition, one Vietnamese wine company is introduced as an example. In order to understand the customers’ behavior regarding Asian food and beverag- es, a quantitative research was conducted. The target group is citizens of Vaasa who are familiar with Asian food in restaurants. The first step is to discover their frequency and their favorite in different types of Asian restaurants presented in Vaasa. The second step is to see how their habits of drinking beverages in those restaurants. Finally, the research focused on how they are willing to taste the local beverages. To conclude, it was found out that Vaasa citizens are often eating Asian food in restaurants, but they are rarely drinking Asian beverages. -

Zielgruppenanalyse Getränke V

Der Markt für Getränke in Vietnam Zielgruppenanalyse im Rahmen der Exportangebote für die Agrar- und Ernährungsindustrie / Februar 2014 www.bmel.de/export Inhalt 1 Einleitung .................................................................................. 6 2 Zur Geopraphie, Politik und Wirtschaft Vietnams ....................................... 8 2.1 Länderprofil Vietnam ...................................................................................................... 8 2.2 Zur Geographie Vietnams ................................................................................................ 9 2.3 Zur Demographie Vietnams ............................................................................................11 2.4 Bildung und Bildungsniveau in Vietnam ..........................................................................12 2.5 Die politischen Rahmenbedingungen Vietnams ..............................................................14 2.6 Die wirtschaftliche Entwicklung Vietnams .....................................................................16 2.7 Der Außenhandel Vietnams ............................................................................................18 2.8 Ausländische Direktinvestitionen in Vietnam .................................................................21 2.9 Infrastuktur, Transportwege und Logistik ......................................................................24 2.9.1 Straßennetz ................................................................................................................24 -

Australia: Increased Market Access Under the TPP-11 Agreement

THIS REPORT CONTAINS ASSESSMENTS OF COMMODITY AND TRADE ISSUES MADE BY USDA STAFF AND NOT NECESSARILY STATEMENTS OF OFFICIAL U.S. GOVERNMENT POLICY Voluntary - Public Date: 5/1/2018 GAIN Report Number: AS1812 Australia Post: Canberra Increased Market Access Under the TPP-11 Agreement Report Categories: Trade Policy Monitoring Agriculture in the News Approved By: Rey Santella, Agricultural Counselor Prepared By: Roger Farrell, Agricultural Specialist Report Highlights: Australia is expected to improve its global competitiveness as the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) Agreement is likely to reduce tariffs and provide significant market access in key markets. Australian beef, pork, fruits, wine, and grains are likely to benefit from the preferential treatment and new trade facilitation arrangements provided under CPTPP. Overview The Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), also known as TPP-11, was signed on March 8, 2018. Members of the agreement include Australia, Brunei, Canada, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru, Singapore, and Vietnam. Overall, the CPTPP will eliminate more than 98 percent of tariffs in the TPP-11 markets, according to the Australian government (see following link: http://dfat.gov.au/trade/agreements/not-yet-in-force/tpp-11/outcomes- documents/Pages/tpp-11-outcomes-at-a-glance.aspx. In 2017, Australia’s agricultural exports to the TPP-11 countries accounted for more than 20 percent of Australia’s total agricultural exports. According to an Australian Parliament assessment, the CPTPP creates valuable new market access opportunities in two TPP-11 markets where Australia does not currently have a free trade agreement (FTA), namely Canada and Mexico. -

GRAPE PRODUCTION in THAILAND 70 by Surasak Nilnond

RAP PUBLICATION: 2001/07 GRAPE PRODUCTION IN THE ASIA-PACIFIC REGION FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS REGIONAL OFFICE FOR ASIA AND THE PACIFIC BANGKOK, THAILAND, JULY 2001 GRAPE PRODUCTION IN THE ASIA-PACIFIC REGION Edited by Minas K. Papademetriou Frank J. Dent FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS REGIONAL OFFICE FOR ASIA AND THE PACIFIC BANGKOK, THAILAND, JULY 2001 This publication brings together edited manuscripts of papers presented at the Expert Consultation on "Viticulture (Grape Production) in Asia and the Pacific", held in Bangkok, Thailand, 2-4 May 2000. The Consultation was organized and sponsored by the FAO Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific. The Report of the Consultation was brought out in August 2000 (RAP Publication:2000/13). The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product for educational or other non-commercial purposes are authorized without any prior written permission from the copyright holders provided the source is fully acknowledged. All rights reserved. Reproduction of material in this information product for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without written permission of the copyright holders. Applications for such permission should be addressed to Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific, Maliwan Mansion, 39 Phra Atit Road, Bangkok 10200, Thailand. -

Part 1 Comprehensive Tasting of Wine Double Gold Tasting Notes From

Summer 2018 Barrels: What They Contribute to Beer, Wine and Liquor - Part 1 Comprehensive Tasting of Wine Double Gold Tasting Notes from the 2018 Tasters Guild International Wine Judging The Mystery of Foam in the Kitchen Retailer‛s Shelf The Beauty of Carménère Those Mystical Moments Ask Tasters Guild Barrels: What They Contribute to The Advent of Barrels for Wine Beer, Wine and Liquor- Part 1 Although the Bourbon whiskey business quickly made charred barrel maturation its signature process, aging By A. Brian Cain wine in new and flavorful barrels really didn’t make much headway until the 1960’s and 1970’s. Certainly barrels Legend has it that Elijah Craig, a preacher and moon- have been used to store wine for many centuries, but, shiner, was bending barrel staves by the traditional winemakers used the same barrels every year and didn’t method of the day with fire. Right in the middle of retire them until they started to leak which may take as bending the staves and assembling a barrel he got called long as a hundred years. Once a barrel has been used for away in an emergency for a dying parishioner. When he maybe 4 or 5 years, it no longer imparts an oak flavor into returned to his barrel, it had become quite charred with the wine though it still retains some residual flavors from the interior looking like black alligator skin. Being a frugal previous batches and importantly is a breeding ground for man of limited means, instead of using the scorched bar- a menagerie of micro-organisms that can favorably affect rel for firewood, he filled it with white lightning. -

Wine and Health Through the Ages

WINE AND HEALTH THROUGH THE AGES WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO AUSTRALIA BY DR. PHILIP NORRIE MBBS (NSW), MSc (Sydney), MSocSc (Hons) (CSU) FPA Cert, FIBA A Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Social Ecology and Lifelong Learning University of Western Sydney 2005 DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to my family - my wife Belinda and my sons Andrew and Alexander for their love and support and to the concept of preventative medicine (the best way to treat a disease is not to get it in the first place) using oenotherapy. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank the following people for helping me research and write my thesis. Professor Stuart Hill, my supervisor for his guidance, patience and support during the whole process - it was much appreciated. Brenda Heagney, the chief librarian at the Medical History Library of the Royal Australasian College of Physicians for her continued support over the years with all my research and books, not just for this PhD thesis. Jan Willoughby, my secretary, for all her typing and clerical assistance. She deserves a medal for reading my handwriting, following my arrows and understanding my "pto's" and "inserts". Dr. Gordon Troup, physicist at Monash University, for sharing his vast knowledge about antioxidants. Shirley Parnell, Secretary of the West Surrey Geneological Society in UK . The staff of each state library, in Australia, Public Records Office in UK, St. Bartholomew's Hospital London, Sydney Hospital and NSW State Archives. All current Wine Doctors for completing their questionnaires. And the families of all past Wine Doctors for providing family histories and documents. -

Vinintell May 2011, Issue 8

VININTELL May 2011, Issue 8 WINE EXPORT MARKET SUSTAINABILITY: EU VERSUS ASIA WINE EXPORT MARKET SUSTAINABILITY: 1. Introduction ••• South African wine exports have shown a According to a report from Vinexpo, demand EU VERSUS ASIA decrease / flattening in the volume of exports for wine in China is exploding, with consump- tion growing 392 percent between 2005 and to major markets like the UK and the rest of 2009. Further growth is expected to rise traditional markets in Europe, while volumes another 56 percent between 2010 and 2014. Welcome to this edition of the quarterly newsletter as a value-added service to members of the to less traditional and new markets like S A Wine Industry. The purpose is to provide you, the decision-maker, with meaningful insight Scandinavia and countries in Asia have ••• into events, trends, opportunities and threats through the analysis of the ever-changing shown an increase. There are various rea- This edition of VinIntell will examine the EU / competitive environment. The analytical approach is a multifaceted, multidisciplinary combination sons behind this development that will be UK vs. the Asian market in terms of growth of scientific and non-scientific processes. discussed in this edition of VinIntell. and decline patterns, unique characteristics We trust that this publication will become part of your strategic thinking, strategic planning and ••• and challenges and opportunities. This edi- decision-making process. You are welcome to send comments and suggestions to the Per capita wine consumption has been falling tion will also seek to provide clarity on the publisher. for decades, especially in southern European question whether wine markets in Asia– countries, where changing consumption Pacific will over time come to substitute the habits (increased outdoor drinking, EU and more specifically and specifically the substitution of other beverages, changing Contents tastes) affect overall demand. -

Asean's Bold New Wine Industry

TRAVELLER ASEAN’S BOLD NEW WINE INDUSTRY In spite of climate and cultural challenges, grape growing and winemaking are getting roots down in Asean ine is one of the world’s oldest countries, contributing to the economies of the countries they are in and providing new tourist attractions. By agricultural products, dating back David Swartzentruber Wabout 10,000 years. Although wine can be produced from any fruit and for some defence from Thailand’s heat and 350 meters and it celebrated its 10th a number of other plants, the wine grape, humidity. The wineries are two to three anniversary this year. The winery is a and chief winemaker at the 3,000 square known as vitis vinifera, has developed as hours drive from Bangkok and are the project of Visooth Lohitnavy and his family meter winery. Khao Yai offers wine in three the prototypical wine. One reason for this Alcidini, Granmonte, Khao Yai and Village that includes wife Sakuna and daughter ranges in ascending order: Sawasdee, is that wine grapes have more juice than Farm Wineries. Nikki, who graduated in 2008 with a PB Reserve Range and Pirom Khao Yai all other fruits. Another is that the wine The Alcidini Winery was started in degree in enology and viticulture from Reserve. The winery has won international grape is a complex plant and often mimics 2001 by Supot Krikpitudh on a hillside 550 the University of Adelaide. The winery awards for its Tempranillo, Shiraz and the flavors of other fruits because of its meters above sea level. At first table grapes offers a complete package, with a guest Chenin Blanc wines. -

Wine Production and Terroir in Mclaren Vale, South Australia

Fermenting Place Wine production and terroir in McLaren Vale, South Australia William Skinner Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In the Discipline of Anthropology, School of Social Sciences University of Adelaide September 2015 Table of Contents List of Figures ...................................................................................................................... iv Abstract .............................................................................................................................. vi Declaration ....................................................................................................................... viii Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................ ix Introduction ........................................................................................................................1 Framing the thesis .............................................................................................................. 4 Dwelling, place and landscape ............................................................................................ 6 Relationality ...................................................................................................................... 15 A terroir perspective ......................................................................................................... 18 Learning from people and vines ...................................................................................... -

The Liberalisation of Trade in Vietnam and Changing Demographics in Society Have Spurred a New Wave of Wine Appreciation in the Country

Hanoi On the streets of Hanoi J NASH J OTOS: OTOS: H P growingThe vine The liberalisation of trade in Vietnam and changing demographics in society have spurred a new wave of wine appreciation in the country. Chris Canty talks to some of the pioneers behind this trend ake a stroll through Hanoi’s Old the pioneer of Vietnam’s wine industry and demographic of Vietnamese who sought high- Quarter and French district and don’t owner of the Vine Wine Boutique Bar & Café quality wine rather than culturally popular be surprised to see framed wine lists featuring Vietnam’s largest wine list, has similar beverages like cheap beer and strong spirits, did T displayed prominently at fine dining impressions. When he arrived in 2000, “the wine restaurants and wholesalers begin to offer better restaurants or small boutique wine shops located lists in the hotels and restaurants were dismal,” and better merchandise. among traditional Hanoi businesses. he says. “The US$4 yellow label Bordeaux 1994 Stores such as the Warehouse and the goliath The Vietnamese might now have a great was everywhere, and I didn’t even believe this supermarket Metro were quick to enter the choice of wine, but it never used to be like this, disgusting product came from French grapes.” game and stock up on an impressive range of And no one knows about the early trials of The Vietnamese interest in Bordeaux was seen high quality wines to a public that for the first Vietnam’s wine industry more than the small as a remnant of the previous French occupation time could afford it. -

Daily News Update

Wednesday, May 19, 2021 www.nabca.org • OR: Merkley Helps Introduce Legislation to End Band on Shipping Alcohol • SC: South Carolina Distilleries Plan Growth With Passage of New Liquor Laws TODAY’S • Tokyo’s restaurateurs rail against alcohol ban as Covid measures bite HIGHLIGHTS • Alcohol use disorder has more stigma surrounding it than do other mental health conditions • Global alcohol sales plummet 15.8bn litres in 2020 CONTROL STATE NEWS NABCA NEWS MI: Michigan Liquor Control Commission Warns Visit NABCA’s COVID-19 Resource page for updates Parents of Underage Drinking Dangers During regarding policy changes that effect on- and off- premise retail operations. Prom and Graduation Season The Collection: An Alcohol Research Summary Press Release (formerly Annotated Bibliography) A comprehensive By the Michigan Liquor Control Commission overview of the latest scientific evidence on May 18, 2021 important topics related to alcohol policy. May 18, 2021 - With prom and graduation season Sharing Solutions E-Newsletter! A platform for the here, the Michigan Liquor Control Commission NABCA community to share successful plementations (MLCC) urges parents to talk with their teens and lessons learned about your good work. about the dangers of underage drinking. Parents are the number one influencer over their kids ADDITIONAL LINKS about making good choices by not consuming alcohol. Visit NABCA’s website for information on: • Control State Agency Information “During this time of celebration, it’s tempting for • Doing Business in Control States our high school students to consume alcohol, • NABCA News especially when they missed out on these memorable events last year with COVID-19 pandemic restrictions,” said MLCC Chair Pat Gagliardi.