Balancing the Aviation Equation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Here Applicants and Recruiters Can • Read All the Magazine Issues of Aero Crew News

September 2016 Aero Crew News Your Source for Pilot Hiring Information and More... Contract Talks Moving Benefits Exclusive Hiring Briefing Aviator Bulletins Upgraded Training Facilities, Partnerships with Schools CPP, internship and more! Fitness Corner Calories in Your Drink, Beware You deserve your dream job. ExpressJet o ers everything that you’re looking for when starting your career. Make the smart choice for your future and fly with the best at ExpressJet. Great Pay o $37-40/hr first year pay o Guaranteed profit sharing program o Leading healthcare benefits Path to the Majors o United Career Path Program o JetBlue University and Advanced Gateways o More pilots hired by the majors each year than any other regional Industry-leading Training o ATP CTP o ered for free (always!) as part of paid training o In-house training tailored to each pilot gives you the best rate of success o Advanced Qualification Program (AQP) Learn more about why ExpressJet is the smart choice for your future at flysmartchoice.com Apply today at expressjet.com/apply You deserve your dream job. ExpressJet o ers everything that you’re looking for when starting your career. Make the smart choice for your future and fly with the best at ExpressJet. Great Pay o $37-40/hr first year pay o Guaranteed profit sharing program Aero Crew Solutions Launches New Website Aero Crew Solutions is proud to announce the complete • The ability for companies to publish their latest o Leading healthcare benefits redesign of our website. Our goal is to continue the job news on our website. -

My Personal Callsign List This List Was Not Designed for Publication However Due to Several Requests I Have Decided to Make It Downloadable

- www.egxwinfogroup.co.uk - The EGXWinfo Group of Twitter Accounts - @EGXWinfoGroup on Twitter - My Personal Callsign List This list was not designed for publication however due to several requests I have decided to make it downloadable. It is a mixture of listed callsigns and logged callsigns so some have numbers after the callsign as they were heard. Use CTL+F in Adobe Reader to search for your callsign Callsign ICAO/PRI IATA Unit Type Based Country Type ABG AAB W9 Abelag Aviation Belgium Civil ARMYAIR AAC Army Air Corps United Kingdom Civil AgustaWestland Lynx AH.9A/AW159 Wildcat ARMYAIR 200# AAC 2Regt | AAC AH.1 AAC Middle Wallop United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 300# AAC 3Regt | AAC AgustaWestland AH-64 Apache AH.1 RAF Wattisham United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 400# AAC 4Regt | AAC AgustaWestland AH-64 Apache AH.1 RAF Wattisham United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 500# AAC 5Regt AAC/RAF Britten-Norman Islander/Defender JHCFS Aldergrove United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 600# AAC 657Sqn | JSFAW | AAC Various RAF Odiham United Kingdom Military Ambassador AAD Mann Air Ltd United Kingdom Civil AIGLE AZUR AAF ZI Aigle Azur France Civil ATLANTIC AAG KI Air Atlantique United Kingdom Civil ATLANTIC AAG Atlantic Flight Training United Kingdom Civil ALOHA AAH KH Aloha Air Cargo United States Civil BOREALIS AAI Air Aurora United States Civil ALFA SUDAN AAJ Alfa Airlines Sudan Civil ALASKA ISLAND AAK Alaska Island Air United States Civil AMERICAN AAL AA American Airlines United States Civil AM CORP AAM Aviation Management Corporation United States Civil -

Approve Airline Lease with Allegiant Air LLC

DRAFT Agenda Item 3 AGENDA STAFF REPORT ASR Control 20-00 l 077 MEETING DATE: 01 /1 2/21 LEGAL ENTITY TAKING ACTION: Board ofSupervisors BOARD OF SUPERVISORS DISTRICT(S): 2 SUBMITTING AGENCY/DEPARTMENT: John Wayne Airport (Approved) DEPARTMENT CONTACT PERSON(S): Barry A. Rondinella (949) 252-5183 Dave Pfeiffer (949) 252-5291 SUBJECT: Approve Airline Lease with Allegiant Air LLC CEO CONCUR COUNTY COUNSEL REVIEW CLERK OF THE BOARD Concur Approved Agreement to Form Discussion 4/5 Vote Budgeted: Yes Current Year Cost: NI A Annual Cost: NIA Staffing Impact: No # of Positions: Sole Source: No Current Fiscal Year Revenue: $614,681 Funding Source: Airport Operating Fund 280: 100% County Audit in last 3 years: No Prior Board Action: 11/03/2020 #6 RECOMMENDED ACTION(S): 1. Approve and execute the Certificated Passenger Airline Lease with Allegiant Air LLC, for a term effective February 1, 2021, through December 31, 2025. 2. Authorize John Wayne Airport to allocate three Regulated Class A Average Daily Departures and seat capacity, effective February I, 2021, through December 31, 2025, consistent with the terms of the Phase 2 Commercial Airline Access Plan and Regulation. 3. Authorize the Airport Director or designee to make minor modifications and amendments to the lease that do not materially alter the terms or financial obligations to the County and perform all activities specified under the terms ofthe lease. SUMMARY: Approval of the Certificated Passenger Airline Lease between the County of Orange and Allegiant Air LLC and approval of the allocation of operating capacity will allow Allegiant Air LLC, a new carrier from the commercial air carrier new entrant waiting list, to initiate operations at John Wayne Airport. -

Nevada-California, USA November 2014

Nevada-California, USA November 2014 While the end of 2014 was approaching, I still had about ten vacation days left. Therefore I decided to spent these on a spotting trip. I teamed up with fellow reader EC and we agreed that the south-western part of the United States would be a great place to visit. The chances of finding nice airplanes and good weather in this part of the world are rather high, even at the end of November. We decided to spend three days in Las Vegas and then drive to southern California, where we would spend almost a full week. The primary focus would be on photographing airliners and fire fighting aircraft, but some number crunching was done as well (although most logs below are not complete). Please note that all mm’s mentioned apply to a 1.5 crop factor camera and all aircraft are only noted once per airport. On the morning of Wednesday 19 November Eddy and I met at Schiphol at approximately 8 AM. There we learned that our flight to Houston was delayed for several hours. Fortunately United Airlines rebooked us on flight UA908 to Chicago. 19 November 2014 Schiphol EHAM G-FBEI Embraer 195LR Flybe LZ-FBE Airbus A320-200 Bulgaria Air N14121 Boeing 757-200 United Airlines N652UA Boeing 767-300ER United Airlines YU-APJ Airbus A319-100 Air Serbia A few planes were noted before boarding the 22-year-old Boeing 767. The flight to Chicago was uneventful in my opinion. However some other passengers complained about the cabin temperature and as a result all passengers received an 100 USD online voucher, to be spent on United Airlines flights with in the next year. -

Abx Air Reaches Tentative Agreement with Pilot Union

Employee Portal Corporate Store ATSG ABX AIR REACHES TENTATIVE AGREEMENT WITH PILOT UNION WILMINGTON, Ohio--(BUSINESS WIRE)--Air Transport Services Group, Inc. (ATSG) said today that its ABX Air subsidiary has reached a tentative agreement to amend the collective bargaining agreement with its pilot group, currently numbering more than 230 flight crew members. ABX Air’s pilots are represented by the Airline Professionals Association of the International Brotherhood of Teamsters, Local 1224 (IBT). The tentative agreement would extend for six (6) years from the date of ratification by the ABX Air pilots. “We are optimistic that this tentative agreement, if ratified, will give ABX Air the opportunity to compete for new growth and provide all our employees with opportunities for career advancement and financial stability,” said ABX Air president David Soaper, “while ensuring that ABX Air continues to provide the excellent service its customers expect.” Terms of the tentative agreement were not disclosed but will be presented to the ABX Air pilot group prior to holding a ratification vote. The vote is expected to be completed prior to the end of the year. About Air Transport Services Group, Inc. (ATSG) ATSG is a leading provider of aircraft leasing and air cargo transportation and related services to domestic and foreign air carriers and other companies that outsource their air cargo lift requirements. ATSG, through its leasing and airline subsidiaries, is the world's largest owner and operator of converted Boeing 767 freighter aircraft. Through its principal subsidiaries, including three airlines with separate and distinct U.S. FAA Part 121 Air Carrier certificates, ATSG provides aircraft leasing, air cargo lift, passenger ACMI and charter services, aircraft maintenance services and airport ground services. -

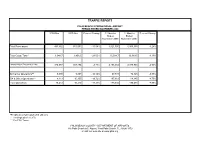

Traffic Report

TRAFFIC REPORT PALM BEACH INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT PERIOD ENDED NOVEMBER 2008 2008/Nov 2007/Nov Percent Change 12 Months 12 Months Percent Change Ended Ended November 2008 November 2007 Total Passengers 493,852 561,053 -11.98% 6,521,590 6,955,356 -6.24% Total Cargo Tons * 1,048.7 1,456.6 -28.00% 15,584.7 16,083.5 -3.10% Landed Weight (Thousands of Lbs.) 326,077 357,284 -8.73% 4,106,354 4,370,930 -6.05% Air Carrier Operations** 5,099 5,857 -12.94% 67,831 72,125 -5.95% GA & Other Operations*** 8,313 10,355 -19.72% 107,861 118,145 -8.70% Total Operations 13,412 16,212 -17.27% 175,692 190,270 -7.66% H17 + H18 + H19 + H20 13,412.0000 16,212.0000 -17.27% 175,692.0000 190,270.0000 -7.66% * Freight plus mail reported in US tons. ** Landings plus takeoffs. *** Per FAA Tower. PALM BEACH COUNTY - DEPARTMENT OF AIRPORTS 846 Palm Beach Int'l. Airport, West Palm Beach, FL 33406-1470 or visit our web site at www.pbia.org TRAFFIC REPORT PALM BEACH INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT AIRLINE PERCENTAGE OF MARKET November 2008 2008/Nov 12 Months Ended November 2008 Enplaned Market Share Enplaned Market Share Passengers Passengers Total Enplaned Passengers 246,559 100.00% 3,273,182 100.00% Delta Air Lines, Inc. 54,043 21.92% 676,064 20.65% JetBlue Airways 50,365 20.43% 597,897 18.27% US Airways, Inc. 36,864 14.95% 470,538 14.38% Continental Airlines, Inc. -

Appendix C Informal Complaints to DOT by New Entrant Airlines About Unfair Exclusionary Practices March 1993 to May 1999

9310-08 App C 10/12/99 13:40 Page 171 Appendix C Informal Complaints to DOT by New Entrant Airlines About Unfair Exclusionary Practices March 1993 to May 1999 UNFAIR PRICING AND CAPACITY RESPONSES 1. Date Raised: May 1999 Complaining Party: AccessAir Complained Against: Northwest Airlines Description: AccessAir, a new airline headquartered in Des Moines, Iowa, began service in the New York–LaGuardia and Los Angeles to Mo- line/Quad Cities/Peoria, Illinois, markets. Northwest offers connecting service in these markets. AccessAir alleged that Northwest was offering fares in these markets that were substantially below Northwest’s costs. 171 9310-08 App C 10/12/99 13:40 Page 172 172 ENTRY AND COMPETITION IN THE U.S. AIRLINE INDUSTRY 2. Date Raised: March 1999 Complaining Party: AccessAir Complained Against: Delta, Northwest, and TWA Description: AccessAir was a new entrant air carrier, headquartered in Des Moines, Iowa. In February 1999, AccessAir began service to New York–LaGuardia and Los Angeles from Des Moines, Iowa, and Moline/ Quad Cities/Peoria, Illinois. AccessAir offered direct service (nonstop or single-plane) between these points, while competitors generally offered connecting service. In the Des Moines/Moline–Los Angeles market, Ac- cessAir offered an introductory roundtrip fare of $198 during the first month of operation and then planned to raise the fare to $298 after March 5, 1999. AccessAir pointed out that its lowest fare of $298 was substantially below the major airlines’ normal 14- to 21-day advance pur- chase fares of $380 to $480 per roundtrip and was less than half of the major airlines’ normal 7-day advance purchase fare of $680. -

Greater Orlando Aviation Authority

Greater Orlando Aviation Authority - Orlando International Airport Landed Weight Statistics For Period OCT-2019 through SEP-2020 Domestic International Airline Name Revenue Non-Revenue Revenue Non-Revenue Total 21 Air, LLC 22,357 22,357 ABC Aerolineas SA de CV 26,771 26,771 ABX Air Inc 3,158 3,158 Aer Lingus Ltd 34,373 34,373 Aerolineas Argentinas S.A. Inc. 16,362 16,362 Aerovias Del Continente Americano-Avianca 38,286 38,286 Pre-Bank Aerovias de Mexico SA de CV 8,192 8,192 Aerovias de Mexico SA de CV Pre- 38,193 38,193 Bankruptcy Air Canada 283,213 283,213 Air Transat A.T. Inc. 27,411 27,411 Alaska Airlines Inc 196,122 196,122 American Airlines Inc 2,187,113 2,187,113 Amerijet International, Inc. 64,184 64,184 Atlas Air Inc. 49,185 6,342 55,527 Azul Linhas Aereas Brasileiras S.A. Inc 142,783 142,783 Bahamasair Holdings Limited, Inc 23,245 23,245 British Airways 90,930 90,930 Caribbean Airlines Limited 11,996 11,996 Concesionaria Vuela Compania Aviacion 23,548 23,548 SAPI de CV Copa Airlines 117,871 117,871 Delta Air Lines 2,188,785 45,992 2,234,777 Eastern Airlines, LLC 278 278 Edelweiss Air AG 1,649 1,649 Emirates Inc 17,174 70,234 87,408 Fast Colombia S.A.S. 284 284 Federal Express Corporation 360,287 360,287 Frontier Airlines 1,696,675 3,246 1,699,921 GOL Linhas Aereas S.A. 33,064 33,064 Hi Fly, Ltd 1,737 1,737 Hi Fly, Transportes Aereos SA 401 401 Icelandair, LLC 28,046 28,046 JetBlue Airways Corp. -

Columbus Regional Airport Authority

COLUMBUS REGIONAL AIRPORT AUTHORITY - PORT COLUMBUS INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT TRAFFIC REPORT June 2014 7/22/2014 Airline Enplaned Passengers Deplaned Passengers Enplaned Air Mail Deplaned Air Mail Enplaned Air Freight Deplaned Air Freight Landings Landed Weight Air Canada Express - Regional 2,377 2,278 - - - - 81 2,745,900 Air Canada Express Totals 2,377 2,278 - - - - 81 2,745,900 AirTran 5,506 4,759 - - - - 59 6,136,000 AirTran Totals 5,506 4,759 - - - - 59 6,136,000 American 21,754 22,200 - - - 306 174 22,210,000 Envoy Air** 22,559 22,530 - - 2 ,027 2 ,873 527 27,043,010 American Totals 44,313 44,730 - - 2,027 3,179 701 49,253,010 Delta 38,216 36,970 29,594 34,196 25,984 36,845 278 38,899,500 Delta Connection - ExpressJet 2,888 2,292 - - - - 55 3,709,300 Delta Connection - Chautauqua 15,614 14,959 - - 640 - 374 15,913,326 Delta Connection - Endeavor 4 ,777 4,943 - - - - 96 5,776,500 Delta Connection - GoJet 874 748 - - 33 - 21 1,407,000 Delta Connection - Shuttle America 6,440 7,877 - - 367 - 143 10,536,277 Delta Connection - SkyWest 198 142 - - - - 4 188,000 Delta Totals 69,007 67,931 29,594 34,196 27,024 36,845 971 76,429,903 Southwest 97,554 96,784 218,777 315,938 830 103,146,000 Southwest Totals 97,554 96,784 - - 218,777 315,938 830 103,146,000 United 3 ,411 3,370 13,718 6 ,423 1 ,294 8 ,738 30 3,990,274 United Express - ExpressJet 13,185 13,319 - - - - 303 13,256,765 United Express - Mesa 27 32 - - - - 1 67,000 United Express - Republic 4,790 5,133 - - - - 88 5,456,000 United Express - Shuttle America 9,825 9,076 - - - - 151 10,919,112 -

Automated Flight Statistics Report For

DENVER INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT TOTAL OPERATIONS AND TRAFFIC March 2014 March YEAR TO DATE % of % of % Grand % Grand Incr./ Incr./ Total Incr./ Incr./ Total 2014 2013 Decr. Decr. 2014 2014 2013 Decr. Decr. 2014 OPERATIONS (1) Air Carrier 36,129 35,883 246 0.7% 74.2% 99,808 101,345 (1,537) -1.5% 73.5% Air Taxi 12,187 13,754 (1,567) -11.4% 25.0% 34,884 38,400 (3,516) -9.2% 25.7% General Aviation 340 318 22 6.9% 0.7% 997 993 4 0.4% 0.7% Military 15 1 14 1400.0% 0.0% 18 23 (5) -21.7% 0.0% TOTAL 48,671 49,956 (1,285) -2.6% 100.0% 135,707 140,761 (5,054) -3.6% 100.0% PASSENGERS (2) International (3) Inbound 68,615 58,114 10,501 18.1% 176,572 144,140 32,432 22.5% Outbound 70,381 56,433 13,948 24.7% 174,705 137,789 36,916 26.8% TOTAL 138,996 114,547 24,449 21.3% 3.1% 351,277 281,929 69,348 24.6% 2.8% International/Pre-cleared Inbound 42,848 36,668 6,180 16.9% 121,892 102,711 19,181 18.7% Outbound 48,016 39,505 8,511 21.5% 132,548 108,136 24,412 22.6% TOTAL 90,864 76,173 14,691 19.3% 2.0% 254,440 210,847 43,593 20.7% 2.1% Majors (4) Inbound 1,698,200 1,685,003 13,197 0.8% 4,675,948 4,662,021 13,927 0.3% Outbound 1,743,844 1,713,061 30,783 1.8% 4,724,572 4,700,122 24,450 0.5% TOTAL 3,442,044 3,398,064 43,980 1.3% 75.7% 9,400,520 9,362,143 38,377 0.4% 75.9% National (5) Inbound 50,888 52,095 (1,207) -2.3% 139,237 127,899 11,338 8.9% Outbound 52,409 52,888 (479) -0.9% 139,959 127,940 12,019 9.4% TOTAL 103,297 104,983 (1,686) -1.6% 2.3% 279,196 255,839 23,357 9.1% 2.3% Regionals (6) Inbound 382,759 380,328 2,431 0.6% 1,046,306 1,028,865 17,441 1.7% Outbound -

Annual Report 2007

EU_ENTWURF_08:00_ENTWURF_01 01.04.2026 13:07 Uhr Seite 1 Analyses of the European air transport market Annual Report 2007 EUROPEAN COMMISSION EU_ENTWURF_08:00_ENTWURF_01 01.04.2026 13:07 Uhr Seite 2 Air Transport and Airport Research Annual analyses of the European air transport market Annual Report 2007 German Aerospace Center Deutsches Zentrum German Aerospace für Luft- und Raumfahrt e.V. Center in the Helmholtz-Association Air Transport and Airport Research December 2008 Linder Hoehe 51147 Cologne Germany Head: Prof. Dr. Johannes Reichmuth Authors: Erik Grunewald, Amir Ayazkhani, Dr. Peter Berster, Gregor Bischoff, Prof. Dr. Hansjochen Ehmer, Dr. Marc Gelhausen, Wolfgang Grimme, Michael Hepting, Hermann Keimel, Petra Kokus, Dr. Peter Meincke, Holger Pabst, Dr. Janina Scheelhaase web: http://www.dlr.de/fw Annual Report 2007 2008-12-02 Release: 2.2 Page 1 Annual analyses of the European air transport market Annual Report 2007 Document Control Information Responsible project manager: DG Energy and Transport Project task: Annual analyses of the European air transport market 2007 EC contract number: TREN/05/MD/S07.74176 Release: 2.2 Save date: 2008-12-02 Total pages: 222 Change Log Release Date Changed Pages or Chapters Comments 1.2 2008-06-20 Final Report 2.0 2008-10-10 chapters 1,2,3 Final Report - full year 2007 draft 2.1 2008-11-20 chapters 1,2,3,5 Final updated Report 2.2 2008-12-02 all Layout items Disclaimer and copyright: This report has been carried out for the Directorate-General for Energy and Transport in the European Commission and expresses the opinion of the organisation undertaking the contract TREN/05/MD/S07.74176. -

Pilots Jump to Each Section Below Contents by Clicking on the Title Or Photo

November 2018 Aero Crew News Your Source for Pilot Hiring and More... ExpressJet is taking off with a new Pilot Contract Top-Tier Compensation and Work Rules $40/hour first-year pay $10,000 annual override for First Officers, $8,000 for Captains New-hire bonus 100% cancellation and deadhead pay $1.95/hour per-diem Generous 401(k) match Friendly commuter and reserve programs ARE YOU READY FOR EXPRESSJET? FLEET DOMICILES UNITED CPP 126 - Embraer ERJ145 Chicago • Cleveland Spend your ExpressJet career 20 - Bombardier CRJ200 Houston • Knoxville knowing United is in Newark your future with the United Pilot Career Path Program Apply today at expressjet.com/apply. Questions? [email protected] expressjet.com /ExpressJetPilotRecruiting @expressjetpilots Jump to each section Below contents by clicking on the title or photo. November 2018 20 36 24 50 32 Also Featuring: Letter from the Publisher 8 Aviator Bulletins 10 Self Defense for Flight Crews 16 Trans States Airlines 42 4 | Aero Crew News BACK TO CONTENTS the grid New Airline Updated Flight Attendant Legacy Regional Alaska Airlines Air Wisconsin The Mainline Grid 56 American Airlines Cape Air Delta Air Lines Compass Airlines Legacy, Major, Cargo & International Airlines Hawaiian Airlines Corvus Airways United Airlines CommutAir General Information Endeavor Air Work Rules Envoy Additional Compensation Details Major ExpressJet Airlines Allegiant Air GoJet Airlines Airline Base Map Frontier Airlines Horizon Air JetBlue Airways Island Air Southwest Airlines Mesa Airlines Spirit Airlines