Trajan's Imperial Alimenta: an Analysis of the Values Attached To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Indian Ocean Trade and the Roman State

The Indian Ocean Trade and the Roman State This thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment of the degree of Master of Research Ancient History at the University of Wales Trinity Saint David, Lampeter Troy Wilkinson 1500107 Word Count: c.33, 000 Footnotes: 7,724 DECLARATION This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signed ............T. Wilkinson ......................................................... (candidate) Date .................10/11/2020....................................................... STATEMENT 1 This thesis is the result of my own investigations, except where otherwise stated. Where correction services have been used the extent and nature of the correction is clearly marked in a footnote(s). Other sources are acknowledged by footnotes giving explicit references. A bibliography is appended. Signed ..................T. Wilkinson ................................................... (candidate) Date ......................10/11/2020.................................................. STATEMENT 2 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed ......................T. Wilkinson ............................................... (candidate) Date ............................10/11/2020............................................ STATEMENT 3 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to -

Violence Against Women on the Column of Marcus Aurelius

Violence Against Women on the Column of Marcus Aurelius The Column of Marcus Aurelius is an imperial Roman monument of uncertain date, like- ly either 176 or 180 CE. Its elements (pedestal, spiral frieze, and statue) and its content (a mili- tary narrative) are largely modeled on the earlier Column of Trajan. One major difference be- tween the columns is that the Column of Marcus Aurelius shows physical violence much more often and more explicitly than the Column of Trajan. This pattern of increased violence on the Column of Marcus Aurelius extends into non-military contexts that involve women. On the Column of Trajan, women never appear alone: they are unthreatened and accompanied by other women and by husbands and/or children. Meanwhile on the Column of Marcus Aurelius, women are more often isolated and sometimes victims of rape and murder. Only one scene on the Col- umn of Marcus Aurelius appears to represent intact unthreatened families. In this scene, XVII, emperor Marcus Aurelius stands on an upper register, while a group of non-Romans gathers on the lower register. The group is composed of families, many with young children. Eugen Petersen, a German scholar, documented the column’s frieze, publishing a series of photographs and descriptions in 1896. In his companion to the frieze, Petersen sug- gests that “perhaps” scene XVII may represent families being separated, though he gives no evi- dence for this claim (Petersen vol. 1, 59). More recently, Paul Zanker has analyzed the scene as part of his work on women and children on the Column of Marcus Aurelius. -

ASKO TIMONEN the Historia Augusta

Criticism of Defense. The Blaming of "Crudelitas" in the "Historia Augusta"* ASKO TIMONEN The Historia Augusta (HA) is the coilection of the biographies of the em perors and famous pretenders from Hadrian to Numerian. It constitutes an enigma in that we know neither its a.uthor nor the exact time of pub lication. For the purpose of this report, I have adopted the broad dating used by P. Soverini, as such a stance provides a general foundation in terms of the research of the history of mentalities and ideologies. Soverini dates publication of the compilation at about the fourth or the fifth century.1 In this paper the concept of crudelitas - the use of "unnecessary" vio lence - shall be discussed with reference to the political situation in a histo riographical sense. Of further interest here is the methodology used in the biographical historiography in that the author utilizes imperial propaganda for his own purpose of blaming a ruler, in this case L. Septimius Severus, of being cruel. To illustrate this concept, I shall interpret the author's comments on the autobiography of Septimius Severus as weil as the au thor's excerpts which were inspired either by this very autobiography or by Severus' speeches to the senate. The author of the HA was weil acquainted with the now-lost autobiography of Septimius Severus: Uxorem tune Mar ciam duxit, de qua tacuit in historia vitae privatae (Sept. Sev. 3.2). Vitam suam privatam publicamque ipse composuit ad fidem, solum tarnen vitium crudelitatis excusans (Sept. Sev. 18.6). In vita sua Severus dicit .. -

Vigiles (The Fire Brigade)

insulae: how the masses lived Life in the city & the emperor Romans Romans in f cus With fires, riots, hunger, disease and poor sanitation being the order of the day for the poor of the city of Rome, the emperor often played a personal role in safeguarding the people who lived in the city. Source 1: vigiles (the fire brigade) In 6 AD the emperor Augustus set up a new tax and used the proceeds to start a new force: the fire brigade, the vigiles urbani (literally: watchmen of the city). They were known commonly by their nickname of spartoli; little bucket-carriers. Bronze water Their duties were varied: they fought fires, pump, used by enforced fire prevention methods, acted as vigiles, called a police force, and even had medical a sipho. doctors in each cohort. British Museum. Source 2: Pliny writes to the emperor for help In this letter Pliny, the governor of Bithynia (modern northern Turkey) writes to the emperor Trajan describing the outbreak of a fire and asking for the emperor’s assistance. Pliny Letters 10.33 est autem latius sparsum, primum violentia It spread more widely at first because of the venti, deinde inertia hominum quos satis force of the wind, then because of the constat otiosos et immobilestanti mali sluggishness of the people who, it is clear, stood around as lazy and immobile spectatores perstitisse; et alioqui nullus spectators of such a great calamity. usquam in publico sipo, nulla hama, nullum Furthermore there was no fire-engine or denique instrumentumad incendia water-bucket anywhere for public use, or in compescenda. -

Byzantium's Balkan Frontier

This page intentionally left blank Byzantium’s Balkan Frontier is the first narrative history in English of the northern Balkans in the tenth to twelfth centuries. Where pre- vious histories have been concerned principally with the medieval history of distinct and autonomous Balkan nations, this study regards Byzantine political authority as a unifying factor in the various lands which formed the empire’s frontier in the north and west. It takes as its central concern Byzantine relations with all Slavic and non-Slavic peoples – including the Serbs, Croats, Bulgarians and Hungarians – in and beyond the Balkan Peninsula, and explores in detail imperial responses, first to the migrations of nomadic peoples, and subsequently to the expansion of Latin Christendom. It also examines the changing conception of the frontier in Byzantine thought and literature through the middle Byzantine period. is British Academy Postdoctoral Fellow, Keble College, Oxford BYZANTIUM’S BALKAN FRONTIER A Political Study of the Northern Balkans, – PAUL STEPHENSON British Academy Postdoctoral Fellow Keble College, Oxford The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 2RU, UK 40 West 20th Street, New York, NY 10011-4211, USA 477 Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne, VIC 3207, Australia Ruiz de Alarcón 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain Dock House, The Waterfront, Cape Town 8001, South Africa http://www.cambridge.org © Paul Stephenson 2004 First published in printed format 2000 ISBN 0-511-03402-4 eBook (Adobe Reader) ISBN 0-521-77017-3 hardback Contents List ofmaps and figurespagevi Prefacevii A note on citation and transliterationix List ofabbreviationsxi Introduction .Bulgaria and beyond:the Northern Balkans (c.–) .The Byzantine occupation ofBulgaria (–) .Northern nomads (–) .Southern Slavs (–) .The rise ofthe west,I:Normans and Crusaders (–) . -

The Roman Augustae: the Most Powerful Women Who Ever Lived a Collection of Six Silver Coins

The Roman Augustae: The Most Powerful Women Who Ever Lived A Collection of Six Silver Coins Frieze of Severan Dynasty All coins in each set are protected in an archival capsule and beautifully displayed in a mahogany-like box. The box set is accompanied with a story card, certificate of authenticity, and a black gift box. The best-known names of ancient Rome are invariably male, and in the 500 years between the reigns of Caesar Augustus and Justinian I, not a single woman held the Roman throne—not even during the chaotic Crisis of the Third Century, when new emperors claimed the throne every other year. This does not mean that women were not vital to the greatest empire the world has ever known. Indeed, much of the time, the real wielders of imperial might were the wives, sisters, and mothers of the emperors. Never was this more true than during the 193-235, when three women—the sisters Julia Maesa and Julia Domna, and Julia Maesa’s daughter Julia Avita Mamaea—secured the succession of their husbands, sons, and grandsons to the imperial throne, thus guaranteeing that they would remain in control. The dynasty is known in the history books as “the Severan,” for Julia Domna’s husband Septimius Severus, but it was the three Julias—and none of the men—who were really responsible for this relatively transition of power. These remarkable women, working in a patriarchal system that officially excluded them from assuming absolute power, nevertheless managed to have their way. Our story begins in Emesa, capital of the Roman client kingdom of Syria, in the year 187 CE. -

The Political and Military Aspects of Accession of Constantine the Great

Graeco-Latina Brunensia 24 / 2019 / 2 https://doi.org/10.5817/GLB2019-2-2 The Political and Military Aspects of Accession of Constantine the Great Stanislav Doležal (University of South Bohemia in České Budějovice) Abstract The article argues that Constantine the Great, until he was recognized by Galerius, the senior ČLÁNKY / ARTICLES Emperor of the Tetrarchy, was an usurper with no right to the imperial power, nothwithstand- ing his claim that his father, the Emperor Constantius I, conferred upon him the imperial title before he died. Tetrarchic principles, envisaged by Diocletian, were specifically put in place to supersede and override blood kinship. Constantine’s accession to power started as a military coup in which a military unit composed of barbarian soldiers seems to have played an impor- tant role. Keywords Constantine the Great; Roman emperor; usurpation; tetrarchy 19 Stanislav Doležal The Political and Military Aspects of Accession of Constantine the Great On 25 July 306 at York, the Roman Emperor Constantius I died peacefully in his bed. On the same day, a new Emperor was made – his eldest son Constantine who had been present at his father’s deathbed. What exactly happened on that day? Britain, a remote province (actually several provinces)1 on the edge of the Roman Empire, had a tendency to defect from the central government. It produced several usurpers in the past.2 Was Constantine one of them? What gave him the right to be an Emperor in the first place? It can be argued that the political system that was still valid in 306, today known as the Tetrarchy, made any such seizure of power illegal. -

The Cambridge Companion to Age of Constantine.Pdf

The Cambridge Companion to THE AGE OF CONSTANTINE S The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Constantine offers students a com- prehensive one-volume introduction to this pivotal emperor and his times. Richly illustrated and designed as a readable survey accessible to all audiences, it also achieves a level of scholarly sophistication and a freshness of interpretation that will be welcomed by the experts. The volume is divided into five sections that examine political history, reli- gion, social and economic history, art, and foreign relations during the reign of Constantine, a ruler who gains in importance because he steered the Roman Empire on a course parallel with his own personal develop- ment. Each chapter examines the intimate interplay between emperor and empire and between a powerful personality and his world. Collec- tively, the chapters show how both were mutually affected in ways that shaped the world of late antiquity and even affect our own world today. Noel Lenski is Associate Professor of Classics at the University of Colorado, Boulder. A specialist in the history of late antiquity, he is the author of numerous articles on military, political, cultural, and social history and the monograph Failure of Empire: Valens and the Roman State in the Fourth Century ad. Cambridge Collections Online © Cambridge University Press, 2007 Cambridge Collections Online © Cambridge University Press, 2007 The Cambridge Companion to THE AGE OF CONSTANTINE S Edited by Noel Lenski University of Colorado Cambridge Collections Online © Cambridge University Press, 2007 cambridge university press Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, Sao˜ Paulo Cambridge University Press 40 West 20th Street, New York, ny 10011-4211, usa www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521818384 c Cambridge University Press 2006 This publication is in copyright. -

Collector's Checklist for Roman Imperial Coinage

Liberty Coin Service Collector’s Checklist for Roman Imperial Coinage (49 BC - AD 518) The Twelve Caesars - The Julio-Claudians and the Flavians (49 BC - AD 96) Purchase Emperor Denomination Grade Date Price Julius Caesar (49-44 BC) Augustus (31 BC-AD 14) Tiberius (AD 14 - AD 37) Caligula (AD 37 - AD 41) Claudius (AD 41 - AD 54) Tiberius Nero (AD 54 - AD 68) Galba (AD 68 - AD 69) Otho (AD 69) Nero Vitellius (AD 69) Vespasian (AD 69 - AD 79) Otho Titus (AD 79 - AD 81) Domitian (AD 81 - AD 96) The Nerva-Antonine Dynasty (AD 96 - AD 192) Nerva (AD 96-AD 98) Trajan (AD 98-AD 117) Hadrian (AD 117 - AD 138) Antoninus Pius (AD 138 - AD 161) Marcus Aurelius (AD 161 - AD 180) Hadrian Lucius Verus (AD 161 - AD 169) Commodus (AD 177 - AD 192) Marcus Aurelius Years of Transition (AD 193 - AD 195) Pertinax (AD 193) Didius Julianus (AD 193) Pescennius Niger (AD 193) Clodius Albinus (AD 193- AD 195) The Severans (AD 193 - AD 235) Clodius Albinus Septimus Severus (AD 193 - AD 211) Caracalla (AD 198 - AD 217) Purchase Emperor Denomination Grade Date Price Geta (AD 209 - AD 212) Macrinus (AD 217 - AD 218) Diadumedian as Caesar (AD 217 - AD 218) Elagabalus (AD 218 - AD 222) Severus Alexander (AD 222 - AD 235) Severus The Military Emperors (AD 235 - AD 284) Alexander Maximinus (AD 235 - AD 238) Maximus Caesar (AD 235 - AD 238) Balbinus (AD 238) Maximinus Pupienus (AD 238) Gordian I (AD 238) Gordian II (AD 238) Gordian III (AD 238 - AD 244) Philip I (AD 244 - AD 249) Philip II (AD 247 - AD 249) Gordian III Trajan Decius (AD 249 - AD 251) Herennius Etruscus -

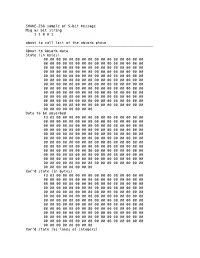

SHAKE-256 Sample of 5-Bit Message

SHAKE-256 sample of 5-bit message Msg as bit string 1 1 0 0 1 about to call last of the absorb phase ------------------------------------------------------------ About to Absorb data State (in bytes) 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 Data to be absorbed F3 03 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 80 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 Xor'd state (in bytes) F3 03 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 -

The Catalyst for Warfare: Dacia's Threat to the Roman Empire

The Catalyst for Warfare: Dacia’s Threat to the Roman Empire ______________________________________ ALEXANDRU MARTALOGU The Roman Republic and Empire survived for centuries despite imminent threats from the various peoples at the frontiers of their territory. Warfare, plundering, settlements and other diplomatic agreements were common throughout the Roman world. Contemporary scholars have given in-depth analyses of some wars and conflicts. Many, however, remain poorly analyzed given the scarce selection of period documents and subsequent inquiry. The Dacian conflicts are one such example. These emerged under the rule of Domitian1 and were ended by Trajan2. Several issues require clarification prior to discussing this topic. The few sources available on Domitian’s reign describe the emperor in hostile terms.3 They depict him as a negative figure. By contrast, the rule of Trajan, during which the Roman Empire reached its peak, is one of the least documented reigns of a major emperor. The primary sources necessary to analyze the Dacian wars include Cassius Dio’s Roman History, Jordanes’ Getica and a few other brief mentions by several ancient authors, including Pliny the Younger and Eutropius. Pliny is the only author contemporary to the wars. The others inherited an already existing opinion about the battles and emperors. It is no surprise that scholars continue to disagree on various issues concerning the Dacian conflicts, including the causes behind Domitian’s and Trajan’s individual decisions to attack Dacia. This study will explore various possible causes behind the Dacian Wars. A variety of reasons lead some to believe that the Romans felt threatened by the Dacians. -

The Roman Army : Military Units You Are Here: Home | Tablets | Tab

The Roman Army : Military Units you are here: home | tablets | Tab. Vindol. II Introductory Chapters | The Roman Army : Military Units Search database Military Units Personnel Soldiers and Civilians Origins Activities List of Persons View tablet number (118-573): From Alan Bowman and David Thomas, The Vindolanda Writing Tablets (Tabulae Vindolandenses II), London: British Museum Press, 1994. pp. 22-24 go In interpreting the evidence of the tablets from the 1970s, we suggested that in the mid-90s Vindolanda was occupied by the quingenary Eighth Cohort of Batavians and that it was succeeded towards the end of the period c. AD 95-105 by View all Tablets the First Cohort of Tungrians, which may have remained in occupation for some years thereafter.2 This interpretation can now be revised and amplified, beginning with the removal from the record of the Eighth Cohort of Batavians, since Search Tablets the evidence which has accumulated subsequently makes it clear that the numeral should have been read as viiii rather than viii.3 Browse Tablets The evidence of the tablets now indicates the certain or possible presence of three cohorts, or parts thereof, at Vindolanda, the First Cohort of Tungrians, the Third Cohort of Batavians and the Ninth Cohort of Batavians. The Search Tablets strength report of the First Cohort of Tungrians (154) shows that the unit was based at Vindolanda and the database archaeological context of this tablet and of the correspondence of its prefect, Iulius Verecundus, indicates that it was Browse Tablets there in the earlier part of the pre-Hadrianic period. The attribution of the strength report to Period 1 now seems less database likely than was once thought and we prefer to regard this particular piece of evidence as attributable to Period 2 and hence to the last decade of the first century AD.