Salmar Burger

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NATIONAL ASSEMBLY QUESTION No. 2026 for WRITTEN REPLY

NATIONAL ASSEMBLY QUESTION No. 2026 FOR WRITTEN REPLY DATE OF PUBLICATION IN INTERNAL QUESTION PAPER: Mr G R Krumbock (DA) to ask the Minister of Sports, Arts and Culture: (1) When last was each national competition of each South African sports federation held; (2) What (a) total number of national federations has the SA Sports Confederation and Olympic Committee (SASCOC) closed down since its establishment and (b) were the reasons in each case; (3) what (a) total number of applications for membership has SASCOC refused since its inception and (b) were the reasons in each case? NW2587E 1 REPLY (1) The following are the details on national competitions as received from the National Federations that responded; National Federations Championship(s) Dates South African Youth Championships October 2019 Wrestling Federation Senior, Junior and Cadet June 2019 Presidents and Masters March 2019 South African South African Equipped Powerlifting Championships 22 February 2020 Powerlifting Federation - Johannesburg Roller Sport South SA Artistic Roller Skating 17 - 19 May 2019 Africa SA Inline Speed skating South African Hockey Indoor Inter Provincial Tournament 11-14 March 2020 Association Cricket South Africa Proteas (Men) – Tour to India, match was abandoned 12 March 2020 without a ball bowled (Covid19 Impacted the rest of the tour). Proteas (Women)- ICC T20 Women’s World Cup 5 March 2020) (Semifinal Tennis South Africa Seniors National Competition 7-11 March 2020 South African Table Para Junior and Senior Championship 8-10 August 2019 Tennis Board -

Download the World Squash Update In

WORLD SQUASH UPDATE Issue 83 November / December 2019 FOR ALL WSF REGIONAL & NATIONAL FEDERATIONS cc: WSF Regional Presidents, WSF Commission Members, Stakeholders, PSA members, SPINs, Media, Accredited Products and Companies CAPE TOWN HOSTS SUCCESSFUL AGM The World Squash Federation Annual General Meeting took place on 6 November in Cape Town, South Africa, hosted by Squash South Africa. The WSF Conference, which preceded the AGM, facilitated informal discussions and featured presentations to update the delegates on key initiatives - including the World Squash Officiating, a joint enterprise between the WSF and Professional Squash Association (PSA) to develop an online platform that will provide National Federations with the tools to develop refereeing in their country. The new initiative is scheduled to go live before the end of the year. Additionally James Sandwith, from BEBRAND, presented the findings of a strategic review commissioned by WSF, with the report now available for all member nations to appraise. The 49th Annual General Meeting, attended by representatives of 24 National Federations, saw delegates agree an amendment to the Articles of Association to reduce the risk of inappropriate leadership behavior and to ensure that delegates in attendance at an AGM have a formal connection with their National Federations. There were no changes to the standard Rules of Squash. However, the Rules of Squash 57 were updated, adding an extra ball rebound resilience at 33 degrees C that will help to ensure that the differential between blue and black balls - and their range of bounce - will be more uniform across the brands that are WSF-approved. The WSF Championship Regulations were updated with respect to player eligibility, the use of random draws and a new timeline and procedure for seeding juniors. -

Judospacenewsletter 2014

Judospace Newsletter 2014 Supporting Player and Coach Education A SNAPSHOT OF OUR AC TIVITIES IN 2014 An Exciting Year At Judospace... December 2014 May nership to deliver EJU Level 3 Visit to Johannesburg South Award in Oslo. Africa to deliver Level 3 EJU Ad- Working to vanced Coach course with Dar- Hellenic Judo Federation partner- ren Warner. ship to deliver the EJU Level 3 improve the Award in Athens, Greece standards of January Partnership established between Dr Mike Callan & Nick Fletcher judo across Athlete Performance Panel Hellenic Judo Federation and the world launched. Judospace. attended the World Kata Cham- pionships and the IJF Kata Train- through im- Rebeka Tandaric & Samobor Judospace 5th Birthday! ing Camp, Malaga, Spain. proving the Judo Klub conduct physiology June knowledge, testing at Anglia Ruskin. Research away day organised by Professor Fumiaki Shishida, Anglia Ruskin Sport & Exercise skills and February Waseda University, visits Ju- Science Research Group. understand- Organised visit of the All Japan dospace offices and Bowen Ar- ing of the coaches, players University Judo Association to chive. Janine Johnson, Judospace Exec- the Budokwai & Oxford Univer- utive Assistant shortlisted in the and federations. Trevor Leggett centenary premi- sity. top 10 for the Newcomer PA of ere at BAFTA, London. the year award by Executive PA March magazine. July Visit from Dr Ryo Uchida of Organised the Commonwealth Nagoya University, Japan. Prof Katsumi Mori from Kanoya Judo Association congress and University visits Judospace to Inside this issue: Coach education seminar for elections in Glasgow. discuss child protection. Judo Federation Iceland. Andy Burns wins Commonwealth Partnership established with GREETINGS FROM 2 Dr Callan met Mr Nikos Iliadis in Games medal. -

A N N U a L R E P O R T 2 0

ANNUAL REPORT 2002 NATIONAL LOTTERIES BOARD Registered address: Block A, Equity Park 257 Brooklyn Road Brooklyn Pretoria 0181 Postal address: P O Box 1556 Brooklyn Square Pretoria 0075 Telephone: +27-12-362 0306 Fax: +27-12-362 2590 Auditors: Auditor-General Bankers: ABSA Nedbank First National Bank Rand Merchant Bank Standard Corporate Merchant Bank NATIONAL LOTTERIES BOARD ANNUAL REPORT 2002 1 Mr. A Erwin Minister of Trade and Industry Report of the National Lotteries Board for the period 1 April 2001 to 31 March 2002. It is my singular honour to submit the Annual Report of the National Lotteries Board and the National Lottery Distribution Trust Fund. J A Foster Chairman 2 NATIONAL LOTTERIES BOARD ANNUAL REPORT 2002 CONTENTS PAGE NO. Chairperson’s Report 4 National Lotteries Board: 13 Report of the Auditor-General 14 Balance Sheet 15 Income Statement 16 Statement of Changes in Equity 17 Cash Flow Statement 18 Notes to the Financial Statements 21 National Lottery Distribution Trust Fund: 27 Report of the Auditor-General 28 Balance Sheet 29 Income Statement 30 Statement of Changes in Equity 31 Cash Flow Statement 32 Notes to the Financial Statements 33 Beneficiaries of Good Cause monies 36 NATIONAL LOTTERIES BOARD ANNUAL REPORT 2002 3 CHAIRPERSON’S REPORT The support of South Africans for the National Lottery in the past two years has been phenomenal. Because of this support, the funds raised by the National Lottery for good causes are making a difference to the lives of the people of South Africa through the promotion of charitable work, the arts, culture, national heritage, sport and recreation. -

AG3403-A1-2-7-004-Jpeg.Pdf

DEVFXOPMENT AND PROMOllON The following proposals were made to help develop and promote table tennis in other areas. 1. A group of players could arrange a visit to areas where there are players interested in developing the game. Eg. Vredendal, Atlantis, Malmesbury, etc. These visits could perhaps be arranged for the off season. 2. A one day tournament could be arranged in areas where tournaments are not normally held. 3. A special team competition could be arranged which would be held at 3 central venues, one each in Boland, Western Province and Malmesbury. The teams would then travel for 2 weeks out of 3. Boland and Western Province are to investigate the possibility of setting this up. 4. Exhibitions 5. Going for weekends to Uitenhage, South Cape. 6. It was proposed that a calender be drawn up setting out the dates of all these event and including normal events on the table tennis calender. 7. It was proposed that the next tournament be held in George. The meeting suggested that a convenor for this tournament be found as soon as possible. The Federation executive was given a mandate to select a steering committee to start organising this tournament immediately. It was also emphasised that this tourna ment will involve a lot of organisation and that everyone would have to pull their weight. 8. Another proposal was that a SATTF team be chosen at the next South African Tournament. They could then be sent on an exhibition tour. 9. It was felt that the standard of umpiring had to be raised. -

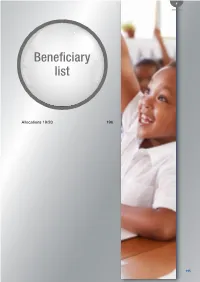

Beneficiary List

F Beneciary list Beneciary list Allocations 19/20 196 National Lotteries Commission Integrated Report 2019/2020 195 ALLOCATIONS 19/20 Date Sector Province Proj No. Name Amount 11-Apr-19 Arts GP 73807 CHILDREN’S RIGHTS VISION (SA) 701 899,00 15-Apr-19 Arts LP M12787 KHENSANI NYANGO FOUNDATION 2 500 000,00 15-Apr-19 Sports GP 32339 United Cricket Board 2 000 800,00 23-Apr-19 Arts EC M12795 OKUMYOLI DEVELOPMENT CENTER 283 000,00 23-Apr-19 Arts KZN M12816 CARL WILHELM POSSELT ORGANISATION 343 000,00 24-Apr-19 Arts MP M12975 MANYAKATANA PRIMARY SCHOOL 200 000,00 24-Apr-19 Arts WC M13008 ACTOR TOOLBOX 286 900,00 24-Apr-19 Arts MP M12862 QUEEN OF RAIN ORPHANAGE HOME 321 005,00 24-Apr-19 Arts MP M12941 GO BACK TO OUR ROOTS 351 025,00 24-Apr-19 Arts MP M12835 LAEVELD NATIONALE KUNSTEFEES 1 903 000,00 29-Apr-19 Charities FS M12924 HAND OF HANDS 5 000 000,00 29-Apr-19 Charities KZN M13275 SIPHILISIWE 5 000 000,00 29-Apr-19 Charities EC M13275 SIPHILISIWE 5 000 000,00 30-Apr-19 Arts FS M13031 ABAFAZI BENGOMA 184 500,00 30-Apr-19 Arts WC M12945 HOOD HOP AFRICA 330 360,00 30-Apr-19 Arts FS M13046 BORN TWO PROSPER 340 884,00 30-Apr-19 Arts FS M13021 SA INDUSTRIAL THEATRE OF DISABILITY 1 509 500,00 30-Apr-19 Arts EC M12850 NATIONAL ARTS FESTIVAL 3 000 000,00 30-Apr-19 Sports MP M12841 Flying Birds Handball Club 126 630,00 30-Apr-19 Sports KZN M12879 Ferry Stars Football Club 128 000,00 30-Apr-19 Sports WC M12848 Blakes Rugby Football Club 147 961,00 30-Apr-19 Sports WC M12930 Riverside Golf Club 200 000,00 30-Apr-19 Sports MP M12809 Mpumalanga Rugby -

Ioc Olympic Studies Centre Advanced Olympic Research Grant Programme 2014/2015

IOC OLYMPIC STUDIES CENTRE ADVANCED OLYMPIC RESEARCH GRANT PROGRAMME 2014/2015 FINAL REPORT OLYMPIC MOVEMENT STAKEHOLDER COLLABORATION FOR DELIVERING ON SPORT DEVELOPMENT IN EIGHT AFRICAN (SADC) COUNTRIES CORA BURNETT UNIVERSITY OF JOHANNESBURG OLYMPIC STUDIES CENTRE (UJOSC) & DEPARTMENT OF SPORT AND MOVEMENT STUDIES, JOHANNESBURG, SOUTH AFRICA May 2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 2 1. INTRODUCTION 2 2. THE RESEARCH 5 2.1 Phases 5 2.2 Aims and objectives 6 3. METHODOLOGY 7 3.1 Research framework 7 3.2 Methods 7 3.3 Sample 7 3.4 Data analysis 9 4. CASE STUDIES 10 4.1 Botswana 10 4.2 Lesotho 15 4.3 Namibia 19 4.4 Seychelles 24 4.5 South Africa 27 4.6 Swaziland 34 4.7 Zambia 37 4.8 Zimbabwe 41 5. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS 45 6. RECOMMENDATIONS 49 7. THE ACADEMIC SIGNIFICANCE OF THE RESEARCH 49 8. REFERENCES 50 9. Annexures 54 Annexure A: Map Annexure B: Pictures Annexure C: Methodology Annexure D: Olympic Education Workshop 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The following agencies are recognised: • The IOC for funding and guidance relating to this research, as well as staff from the International Olympic Study Centre, especially Nuria Puig, for assistance during the research process. • All leadership at in-country NOCs and competent staff members for assisting with logistical arrangements and providing in-country support. The wide reach is contributed to them identifying research participants, providing a venue, local guide and venue when needed. • All research participants who committed their time and shared their expertise during often long and intricate discussions and interviews. -

Annual Report

PART A General Informati on TM ANNUAL REPORT 2016/17 1 Annual Report of National Lotteries Commission 2016/17 TM © National Lotteries Commission Annual Report 2016/17 ISBN: 978-0-621-45535-9 Published by the National Lotteries Commission All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means, without the prior written consent of the National Lotteries Commission. Annual Report of National Lotteries Commission 2016/17 2 PART A General Informati on 3 Annual Report of National Lotteries Commission 2016/17 TABLE OF CONTENTS Annual Report of National Lotteries Commission 2016/17 4 PART A General Informati on PART A GENERAL INFORMATION...................................................8 1. General Information......................................................................................10 2. List of Abbreviations/Acronyms....................................................................11 3. Foreword by the Minister.......……………………….......................................13 4. Foreword by the Chairperson……………………….......................................15 5. Commissioner’s Overview………………....................................................…17 6. Statement of responsibility and con rmation of the accuracy of the annual report…...................................................................................20 7. Strategic Overview……………….............................................................…..22 8. Legislative Mandate..….................................................................................23 -

2014 Annual Report

2014 ANNUAL REPORT Report and financial statements For year ending 31 December 2014 BCA ANNUAL REPORT 2014 PAGE 1 Table of Contents OFFICERS ....................................................................................................................................................... 2 ADMINISTRATION .......................................................................................................................................... 2 FROM THE PRESIDENT AND CHAIR OF DEVELOPMENT ................................................................................... 3 2014 BCA COUNCIL REPORT ........................................................................................................................... 4 INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................................... 4 MEMBERSHIP ............................................................................................................................................ 5 REGIONS & OPERATION structures............................................................................................................. 5 DEVELOPMENT .......................................................................................................................................... 6 GOVERNANCE ............................................................................................................................................ 7 2014 BCA COMMITTEES ............................................................................................................................ -

Annual Report 2 0

ANNUAL REPORT 2003 NATIONAL LOTTERIES BOARD Registered address: Block A, Equity Park 257 Brooklyn Road Brooklyn Pretoria 0181 Postal address: P O Box 1556 Brooklyn Square Pretoria 0075 Telephone: +27-12-362 0306 Fax: +27-12-362 2590 Auditors: Auditor-General Bankers: ABSA Nedbank First National Bank Rand Merchant Bank Standard Corporate Merchant Bank NATIONAL LOTTERIES BOARD annual report 2003 1 Mr. A Erwin Minister of Trade and Industry Report of the National Lotteries Board for the period 1 April 2002 to 31 March 2003. It is my singular honour to submit the Annual Report of the National Lotteries Board and the National Lottery Distribution Trust Fund. J A Foster Chairman NATIONAL LOTTERIES BOARD annual report 2003 2 CONTENTS PAGE NO Chairperson’s Report 4 Audit Committee Report 13 National Lotteries Board: Report of the Auditor-General 15 Board Report 16 Balance Sheet 19 Income Statement 20 Statement of Changes in Equity 21 Cash Flow Statement 22 Summary of Accounting Policies 23 Notes to the Annual Financial Statements 25 National Lottery Distribution Trust Fund: Report of the Auditor-General 34 Balance Sheet 36 Income Statement 37 Statement of Changes in Equity 38 Cash Flow Statement 39 Notes to the Annual Financial Statements 40 Beneficiaries of Good Cause Monies 43 NATIONAL LOTTERIES BOARD annual report 2003 3 CHAIRPERSON’S REPORT One of the most identifiable brands in South Africa today is the National Lottery logo. Initially, the logo was associated with entertainment and the chance to fulfil one’s wildest dreams but it has come to mean something more profound. Each day, the National Lottery changes the lives of millions in South Africa in different ways. -

CORRUPTION the MEDIA SACOS Operates in Such a Climate in South

Ramsamy had, however, delivered the goods and had assured his position as Chairman of NOCSA until the next Olympic Games and perhaps until 2004, should South Africa be granted the Games for that year. He had also duly rewarded some of those who like him had betrayed the non-racial cause. One wonders if he did not at times have nightmares or was not haunted by what he wrote in “Apartheid - The Real Hurdle” “Black school children - the raw material from which future black sportsmen and women are made - are forced to accept inferior and unequal facilities. It is in reality impossible to conceive o f a completely non-racial sports system in a country which in these much more fundamental respects treats more than 80 percent of the population differently on the grounds o f race and colour. Merit selection emanating out o f such a system has little or no meaning as it will tend to prove how mediocre the performance o f black sportspeople are - the very theory that the white racist regime is propagating internationally. ” The final communique issued by the ANOCA Conference in Harare on 3/4 November 1990 stipulated that “once apartheid has been totally abolished” unity should be formed by the organisations controlling sport and the readmission of South Africa to membership of international sports organisations may be considered. One wonders whether Ramsamy has suffered a Craven-type loss of memory or has suddenly developed blind spots in that faculty. CORRUPTION Where money is, there is corruption, from the seller of fancy goods to the multi-millionaire. -

Sport and Recreation South Africa (SRSA) Is the National Government Department Responsible for Sport in South Africa

Sport and Recreation South Africa (SRSA) is the national government department responsible for sport in South Africa. Aligned with its vision of creating An Active and Winning Nation, its primary focuses are providing opportunities for all South Africans to participate in sport; managing the regulatory framework thereof and providing funding for different codes of sport. The department transforms the delivery of sport and recreation by ensuring equitable access, development and excellence at all levels of participation, thereby improving social cohesion, nation-building and the quality of life of all South Africans. The SRSA is established in terms of the Public Service Act of 1994. Its legal mandate is derived from the National Sport and Recreation Amendment Act, 2007 (Act 18 of 2007), which requires it to oversee the development and management of sport and recreation in South Africa. The Act provides the framework for relationships between the department and its external clients. This includes the SRSA’s partnership with the South African Sports Confederation and Olympic Committee (SASCOC). The partnership is key to improving South Africa’s international ranking in selected sports. The Act also ensures that sport and physical education contribute to social cohesion by legislating on sports participation and sports infrastructure. Aligned with the SRSA’s vision of an active and winning nation, the department primarily focuses on providing opportunities for all South Africans to participate in sport; manages the regulatory framework; and provides funding for different sporting codes. The SRSA aims to maximise access, development and excellence at all levels of participation in sport and recreation to improve the quality of life for all South Africans.