No Systematic Doping in Football”: a Critical Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Romanian Football Federation: in Search of Good Governance”

“Romanian Football Federation: in search of good governance” Florian Petrică Play The Game 2017 Eindhoven, November 29 LPF vs FRF Control over the national team and distribution of TV money Gigi Becali, FCSB owner (former Razvan Burleanu, FRF president Steaua) “The future is important now. Burleanu is - under his mandate, the Romanian national a problem, he should go, it is necessary team was led for the first time by a foreign to combine the sports, journalistic and coach – the German Christoph Daum political forces to get him down. National forces must also be involved to take him - has attracted criticism from club owners after down" Gigi Becali proposing LPF to cede 5% of TV rights revenue to lower leagues. Romanian teams in international competitions The National Team World Cup 1994, SUA: the 6th place 1998, France: latest qualification FIFA ranking: 3-rd place, 1997 The European Championship 2000, Belgium - Netherlands: the 7-th place National was ranked 7th 2016: latest qualification (last place in Group A, no win) FIFA ranking: 41-st place, 2017 The Romanian clubs 2006: Steaua vs Rapid in the quarterfinals of the UEFA Cup. Steaua lost the semi-final with Middlesbrough (2-4) ROMANIA. THE MOST IMPORTANT FOOTBALL TRANSFERS. 1990-2009 No Player Club Destination Value (dollars) Year 1. Mirel Rădoi Steaua Al Hilal 7.700.000 2009 2. Ionuţ Mazilu Rapid Dnepr 5.200.000 2008 3. Gheorghe Hagi Steaua Real Madrid 4.300.000 1990 4. George Ogararu Steaua Ajax 4.000.000 2006 5. Adrian Ropotan Dinamo Dinamo Moscova 3.900.000 2009 6. -

Two Day Sporting Memorabilia Auction - Day 2 Tuesday 14 May 2013 10:30

Two Day Sporting Memorabilia Auction - Day 2 Tuesday 14 May 2013 10:30 Graham Budd Auctions Ltd Sotheby's 34-35 New Bond Street London W1A 2AA Graham Budd Auctions Ltd (Two Day Sporting Memorabilia Auction - Day 2) Catalogue - Downloaded from UKAuctioneers.com Lot: 335 restrictions and 144 meetings were held between Easter 1940 Two framed 1929 sets of Dirt Track Racing cigarette cards, and VE Day 1945. 'Thrills of the Dirt Track', a complete photographic set of 16 Estimate: £100.00 - £150.00 given with Champion and Triumph cigarettes, each card individually dated between April and June 1929, mounted, framed and glazed, 38 by 46cm., 15 by 18in., 'Famous Dirt Lot: 338 Tack Riders', an illustrated colour set of 25 given with Ogden's Post-war 1940s-50s speedway journals and programmes, Cigarettes, each card featuring the portrait and signature of a including three 1947 issues of The Broadsider, three 1947-48 successful 1928 rider, mounted, framed and glazed, 33 by Speedway Reporter, nine 1949-50 Speedway Echo, seventy 48cm., 13 by 19in., plus 'Speedway Riders', a similar late- three 1947-1955 Speedway Gazette, eight 8 b&w speedway 1930s illustrated colour set of 50 given with Player's Cigarettes, press photos; plus many F.I.M. World Rider Championship mounted, framed and glazed, 51 by 56cm., 20 by 22in.; sold programmes 1948-82, including overseas events, eight with three small enamelled metal speedway supporters club pin England v. Australia tests 1948-53, over seventy 1947-1956 badges for the New Cross, Wembley and West Ham teams and Wembley -

Caderno Eleitoral Columbofilos

CADERNO ELEITORAL Circulo Eleitoral Porto Columbófilos Licença X Nome Federativa ABEL CARNEIRO SOUSA RODRIGUES 6408 ABEL FERREIRA LEITE 26304 ABEL FERREIRA REIS 6823 ABEL FERREIRA VALE 6394 ABEL MARIO SILVA PEREIRA 22190 ABEL ROCHA OLIVEIRA 52747 ABEL SILVA ALVES 26011 ABEL SOUSA FERNANDES 5117 ABEL XAVIER MARTINS NETO 39641 ABILIO ALBINO ANTUNES MARTINS 47508 ABILIO ANTONIO MENDES AZEVEDO 17467 ABILIO COSTA ALVES BASTOS 22735 ABILIO FERREIRA SANTOS 44918 ABILIO GONCALVES PEREIRA 38110 ABILIO GONCALVES SERRA 23222 ABILIO JORGE BARBOSA VIANA 27404 ABILIO LOPES PEREIRA 22581 ABILIO MANUEL F FRANCISCO 51267 ABILIO MARTINS NEVES 32119 ABILIO MIRANDA CARVALHO 36820 ABILIO MOREIRA NETO 22563 ABILIO OLIVEIRA MOREIRA 17585 ABILIO OLIVEIRA SILVA 6829 ABILIO OLIVEIRA SILVA 6871 ABILIO SERGIO F PEREIRA 45504 ABILIO SILVA ARAUJO 42465 ABILIO SILVA CUSTODIO 42668 ABILIO SILVA MACHADO 38281 ABILIO TEIXEIRA SOUSA 6447 ACACIO FERNANDO JESUS 40996 ACACIO LOPES AMORIM 2696 Licença X Nome Federativa ACACIO MACHADO RIBEIRO 5287 ACACIO VIEIRA MOTA 17657 ACILIO SOUSA CASTRO 5823 ADALBERTO FERNANDO MAIA NEVES 17824 ADAO ANTONIO DUARTE TEIXEIRA 46136 ADAO EDUARDO SOARES MOURA 42502 ADAO FERNANDO T CAMOES RIBEIRO 35819 ADAO MANUEL ALMEIDA SILVA 47991 ADAO MANUEL ALVES SILVA 27325 ADAO MOURA CARDOSO 37054 ADELINO ALMEIDA GONCALVES 22481 ADELINO ANTONIO T MOREIRA 30384 ADELINO BERNARDO G MOTA 48000 ADELINO JOAQUIM S LEONARDO 30251 ADELINO MANUEL R FERNANDES 50383 ADELINO MOREIRA ROCHA 39313 ADELINO VEIGA CARVALHO 38425 ADELIO ROCHA OLIVEIRA 44957 ADERITO NEVES -

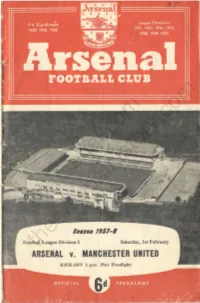

Arsenal.Com Thearsenalhistory.Com

arsenal.com Se11so11 1951-8 Footballthearsenalhistory.com League Division I Saturday, lst February ARSENAL v. MANCHESTER UNITED 'KICK-OFF 3 p.m. (Part Floodlight) lors who had come particularly to see our friendly match at Hereford last April and ARSENAL FOOTBALL CLUB LIMITED new signings-Ronnie Clayton and Freddie when we approached our old colleague Joe Jones-both from Hereford United. Here Wade, who is man;iger of the team nowa Directors again it was a story of the goalkeeper days, it was arranged that we should talk SIR BRACBWBLL :>Mira, Bart., K.C.V.O. (C hairman) keeping down the score, for Maclaren in about it again after they had been elimin CoMMANDBR A. F. BoNB, R.o., R.N.R., asro. 1he City goal was in great form to make ated from the F.A. Cup. This we did after J. W. JOYCE, EsQ. spectacular saves from Ray Swallow, Tony the 3rd Round and everything was fixed D. J. C. H. HILL-WOOD, EsQ. G. BRAcswsu.-SMITH, EsQ., M.B.B., e.A . Biggs and Freddie Jones. up in very quick time. We wish these two Secretary First, he made a full-length, one-handed youngsters every success at Highbury and W .R. WALL. save from Jones and followed it up with a long sojourn with our club. Manager a backward somersault in saving from Last Saturday we played a Friendly W. J. CRAYSTON. Biggs. Then Newman, the centre-half, match at Swansea in most difficult con kicked off the line when a shot from Swal ditions. The thaw had set in and the pitch low seemed certain to go in and Mac was thoroughly wet and sloppy. -

FC Famalicão SL Benfica

JORNADA 31 FC Famalicão SL Benfica Quinta, 09 de Julho 2020 - 21:30 Estádio Municipal de Famalicão, Vila Nova de Famalicão ORGANIZADOR POWERED BY Jornada 31 FC Famalicão X SL Benfica 2 Confronto histórico Ver mais detalhes FC Famalicão 1 2 14 SL Benfica GOLOS / MÉDIA VITÓRIAS EMPATES VITÓRIAS GOLOS / MÉDIA 13 golos marcados, uma média de 0,76 golos/jogo 6% 12% 82% 48 golos marcados, uma média de 2,82 golos/jogo TOTAL FC FAMALICÃO (CASA) SL BENFICA (CASA) CAMPO NEUTRO J FCF E SLB GOLOS FCF E SLB GOLOS FCF E SLB GOLOS FCF E SLB GOLOS Total 17 1 2 14 13 48 1 2 5 5 16 0 0 9 8 32 0 0 0 0 0 Liga NOS 13 1 1 11 9 40 1 1 4 4 14 0 0 7 5 26 0 0 0 0 0 Taça de Portugal 4 0 1 3 4 8 0 1 1 1 2 0 0 2 3 6 0 0 0 0 0 J=Jogos, E=Empates, FCF=FC Famalicão, SLB=SL Benfica FACTOS FC FAMALICÃO FACTOS SL BENFICA TOTAIS TOTAIS 82% vitórias 82% derrotas 6% derrotas 59% em que marcou 88% em que marcou 88% em que sofreu golos 59% em que sofreu golos MÁXIMO MÁXIMO 1 Jogos a vencer 8 Jogos a vencer 1947-01-12 -> 1992-02-19 9 Jogos sem vencer 1947-01-12 -> 1992-04-05 2 Jogos sem vencer 1992-04-05 -> 1992-09-13 8 Jogos a perder 1947-01-12 -> 1992-02-19 1 Jogos a perder 2 Jogos sem perder 1992-04-05 -> 1992-09-13 9 Jogos sem perder 1947-01-12 -> 1992-04-05 RECORDES FC FAMALICÃO: MAIOR VITÓRIA EM CASA Liga Portuguesa 1992/93 FC Famalicão 1-0 SL Benfica SL BENFICA: MAIOR VITÓRIA EM CASA Liga Portuguesa 1993/94 SL Benfica 8-0 FC Famalicão SL BENFICA: MAIOR VITÓRIA FORA Liga Portuguesa 1993/94 FC Famalicão 1-5 SL Benfica I Divisão 1946/47 FC Famalicão 1-5 SL Benfica RESULTADO -

18Futbol Camino a Corea Y Japón

Miércoles 13 de febrero de 2002 Mundo Deportivo 18 FUTBOL CAMINO A COREA Y JAPÓN España y Camacho Portugal miden motiva hoy sus fuerzas recordando que pensando en la la lista de 23 gran cita Sabor está abierta aMundial Javier Gascón BARCELONA ESPAÑA PORTUGAL ólo es un amistoso, pue- TÉCNICO MONTJUÏC TÉCNICO Montjuïc se den pensar algunos, pero J. ANTONIO ANTONIO CAMACHO RICARDO OLIVEIRA esta noche la selección se CAÑIZARES 'TONI' llenó hace dos S SALGADO NADAL J. COSTA DIMAS juega algo más que el pres- PUYOL COUTO tigio ante Portugal, otra selección años ante Italia MENDIETA SERGI FRECHAUT PAULO BENTO con aspiraciones en el Mundial. HELGUERA VIDIGAL JOAO PINTO De lo que ocurra esta noche depen- P. BARBOSA Quizás no se alcance en el Estadi MORIENTES de que la afición vuelva a ilusio- VALERÓN VICENTE Olímpic de Montjuïc el FIGO PAULETA narse y a engancharse con España extraordinario ambiente del TRISTÁN Alessandro Todor tal y como sucedió antes de la amistoso de hace dos años contra (Rumanía) Eurocopa, aunque luego no llega- Italia (2-0), el 29 de marzo de TITULARES TITULARES ra el éxito soñado. El resultado es VISITAS DE PORTUGAL A ESPAÑA 2000, cuando cerca de 50.000 1 1 importante, pero mucho más la CAÑIZARES MORIENTES 18-12-1921 Amistoso ESP-POR, 3-1 Madrid RICARDO espectadores comenzaron a soñar 2 SALGADO FRECHAUT 2 actitud, el carácter y el juego que 16-12-1923 Amistoso ESP-POR, 3-0 Sevilla con un éxito en la Eurocopa que no 3 SERGI 17-03-1929 Amistoso ESP-POR, 5-0 Sevilla DIMAS 3 se desplegue sobre el césped del 4 PUYOL 02-04-1933 Amistoso ESP-POR, 3-0 Vigo JORGE COSTA 4 llegó, pero las previsiones para Estadi Olímpic de Montjuïc. -

Calcio Ucronico

Eccoci Signori, bentornati su Sky Sport 24 per l’edizione delle 18, il calciomercato è finito, si ricomincia a fare sul serio, siamo ormai entrati in una nuova stagione, e sarà una stagione bellissima! Ecco il servizio preparato dalla nostra redazione su questo nuovo anno di grande calcio, tutto in diretta sulla nuova piattaforma SKY, che trasmette tutto il calcio italiano e internazionale in collaborazione con la Radio Televisione Toscana, TeleNord e Napoli TV. Via col servizio: ******************************************************************************************* A un anno dalla vittoria spagnola degli Europei 2008 sulla nazionale alto italiana i cugini dei castigliani si vendicano, infatti il Barcellona campione di Catalogna conquista la sua terza Champions League sconfiggendo in finale il Manchester United. Ma ora ricomincia il calcio europeo e italiano, in una nuova emozionante stagione! Ecco le squadre schierate nei prossimi campionati e coppe italiani: Alta Italia (FCAI) Serie A 2009/2010, campionato a girone unico con andata e ritorno Albinoleffe Milan Atalanta Modena Brescia Padova Cagliari Parma Chievo Verona Piacenza Como Sampdoria Genoa Sassuolo Inter Torino Juventus Triestina Mantova Udinese Toscana (LCT) Lega A 2009/2010, campionato a girone unico con doppio girone di andata e ritorno Arezzo Livorno Empoli Perugia Fiorentina Siena Grosseto Ternana Due Sicilie (FGCDS) Lega 1 2009/2010, campionato a girone unico con doppio girone di andata e ritorno Bari Messina Catania Napoli Gallipoli Palermo Lecce Reggina Stato Pontificio -

You Go Ahead, Cause Its Making Me Laugh... by Fausto Sala - Vice President FISSC

Year Number Jan - Mar 2 1 2012 You go ahead, cause its making me laugh... by Fausto Sala - Vice President FISSC “Olimpico” stadium in Rome, Sunday 5 February 2012. Around the 20 minute of the first half of Roma-Inter in South stand appeared a banner which read: “All at 15: the nature of things, by nature force”. As everybody knows the match was scheduled to be played on Saturday at 20.45, then anticipated at 15 and at last moved at the same time on Sunday, in contemporary with all other matches in serie A as the tradition was back in the past. Thus the roman fans wanted to underline this fact and their consent for the traditional shcedule of matches, remarking as only the snow emergency had forced the hands of those in command to revert to old habits of italian football fans. We can repeat until boredom that playing at night in the coldest days of the year is madness. Yet since January 18 up to February 5, between league and national cup, 21 matches at night have been programmed and out of these 19 in the north between Bergamo, Milan, Torino or Novara. But you think that who decides does not know such facts? But more the Lega is criticised, and more who guides the Lega continues to be bend to the will of the television networks who now have absolute power to decide the time in which games are playes, having tv rights now constitute the main income for the clubs. Thus the only concern of the Lega in these last seasons, whose president Maurizio Beretta has resigned since March of last year since he now passed to a top managerial post within UniCredit, was to see how to divide between the clubs the income coming from these rights with the consequent effect of half-empty stadiums to the benefit of sitting in cosy armchairs and sofas at home. -

Former FIFA President Havelange Resigns from IOC

14 Tuesday 6th December, 2011 Former FIFA President Havelange resigns from IOC by Stephen Wilson Blatter, who is also an IOC member, said in October that FIFA’s executive committee would LONDON (AP) — Former FIFA President Joao “reopen” the ISL dossier at a Dec. 16-17 meeting in Havelange has resigned from the IOC, just days Tokyo as part of a promised drive toward trans- before the longtime Brazilian member faced sus- parency and zero tolerance of corruption. pension from the Olympic body in a decade-old Hayatou and Diack face likely warnings or rep- kickback scandal stemming from his days as the rimands — not formal suspensions — from the IOC head of world football, The Associated Press has for conflict of interest violations in the ISL affair. learned. Hayatou, an IOC member since 2001 and Africa’s The 95-year-old Havelange — the IOC’s longest- top football official, reportedly received about serving member with 48 years of service — submit- $20,000 from ISL in 1995. He has denied any corrup- ted his resignation in a letter Thursday night, tion and said the money was a gift for his confeder- according to a person familiar with the case. The ation. Simon Katich person spoke to the AP on Sunday on condition of Diack said he received money after his house in anonymity because Havelange’s decision has been Senegal burned down in 1993. Diack, who was not kept confidential. an IOC member at the time, has said he did nothing Katich reprimanded The move came a few days before the wrong and is confident of being cleared. -

Match Report

Match Report 2002 FIFA World Cup Korea/Japan™ Group D Portugal - Korea Republic 0:1 (0:0) Match Date Venue / Stadium / Country Time Att 47 14 JUN 2002 Incheon / Incheon Munhak Stadium / KOR 20:30 50,239 Goals Scored: PARK Ji Sung (KOR) 70' Portugal (POR) Korea Republic (KOR) [ 1] VITOR BAIA (GK) [ 1] LEE Woon Jae (GK) [ 2] JORGE COSTA [ 4] CHOI Jin Cheul [ 5] FERNANDO COUTO (C) [ 5] KIM Nam Il [ 7] LUIS FIGO [ 6] YOO Sang Chul [ 8] JOAO PINTO [ 7] KIM Tae Young [ 9] PAULETA (-69') [ 9] SEOL Ki Hyeon [ 11] SERGIO CONCEICAO [ 10] LEE Young Pyo [ 17] PAULO BENTO [ 19] AHN Jung Hwan (-93') [ 20] PETIT (-77') [ 20] HONG Myung Bo (C) [ 22] BETO [ 21] PARK Ji Sung [ 23] RUI JORGE (-73') [ 22] SONG Chong Gug Substitutes: Substitutes: [ 3] ABEL XAVIER (+73') [ 2] HYUN Young Min [ 4] CANEIRA [ 3] CHOI Sung Yong [ 6] PAULO SOUSA [ 8] CHOI Tae Uk [ 10] RUI COSTA [ 11] CHOI Yong Soo [ 12] HUGO VIANA [ 12] KIM Byung Ji (GK) [ 13] JORGE ANDRADE (+69') [ 13] LEE Eul Yong [ 14] PEDRO BARBOSA [ 14] LEE Chun Soo (+93') [ 15] NELSON (GK) [ 15] LEE Min Sung [ 16] RICARDO (GK) [ 16] CHA Du Ri [ 18] FRECHAUT [ 17] YOON Jong Hwan [ 19] CAPUCHO [ 18] HWANG Sun Hong [ 21] NUNO GOMES (+77') [ 23] CHOI Eun Sung (GK) Coach:OLIVEIRA Antonio (POR) Coach: HIDDINK Guus (NED) Cautions: BETO (POR) 22' , KIM Tae Young (KOR) 24' , SEOL Ki Hyeon (KOR) 57' , BETO (POR) 66' , KIM Nam Il (KOR) 74' , JORGE COSTA (POR) 83' , AHN Jung Hwan (KOR) 93' Expulsions: JOAO PINTO (POR) 27' , BETO (POR) 66' 2Y Match Officials: Referee:SANCHEZ Angel (ARG) Assistant Referee 1: AL TRAIFI Ali -

Wizards O.T. Coast Football Champions

www.soccercardindex.com Wizards of the Coast Football Champions France 2001/02 checklist France National Team □63 Claude Michel Bordeaux Paris St. Germain □1 Fabien Barthez □64 Abdelhafid Tasfaout □124 Ulrich Rame □185 Lionel Letizi □2 Ulrich Rame □65 Fabrice Fiorese □125 Kodjo Afanou □186 Parralo Aguilera Cristobal □3 Vincent Candela □66 Stephane Guivarc'h □126 Bruno Miguel Basto □187 Frederic Dehu □4 Marcel Desailly □127 David Jemmali □188 Gabriel Heinze □5 Frank Leboeuf Troyes □128 Alain Roche □189 Mauricio Pochettino □6 Bixente Lizarazu □67 Tony Heurtebis □129 David Sommeil □190 Lionel Potillon □7 Emmanuel Petit □68 Frederic Adam □130 Laurent Batles □191 Mikel Arteta □8 Willy Sagnol □69 Gharib Amzine □131 Christophe Dugarry □192 Edouard Cisse □9 Mickael Silvestre □70 Mohamed Bradja □132 Sylvain Legwinski □193 Jay Jay Okocha □10 Lilian Thuram □71 David Hamed □133 Paulo Miranda □194 Ronaldinho □11 Eric Carriere □72 Medhi Leroy □134 Alexei Smertin □195 Jose Aloisio □12 Christophe Dugarry □73 Olivier Thomas □135 Christian □196 Nicolas Anelka □13 Christian Karembeu □74 Fabio Celestini □136 Pauleta □14 Robert Pires □75 Jerome Rothen Lens □15 Patrick Vieira □76 Samuel Boutal Lille □197 Guillaume Warmuz □16 Zinedine Zidane □77 Nicolas Gousse □137 Gregory Wimbee □198 Ferdinand Coly □17 Nicolas Anelka □138 Pascal Cygan □199 Valerien Ismael □18 Youri Djorkaeff Lorient □139 Abdelilah Fahmi □200 Eric Sikora □19 Thierry Henry □78 Stephane le Garrec □140 Stephane Pichot □201 Jean Guy Wallemme □20 Laurent Robert □79 Christophe Ferron □141 Gregory -

Presskit Supertaça2013 Site.Pdf

1 Histórico da Supertaça Cândido de Oliveira Prova Oficial Época Vencedor Data Jogo Local 2011/12 FC Porto 11.08.2012 FC Porto 1-0 Académica AAC Municipal de Aveiro 2010/11 FC Porto 07.08.2011 FC Porto 2-1 Vitória SC Municipal de Aveiro 2009/10 FC Porto 07.08.2010 SL Benfica 0-2 FC Porto Municipal de Aveiro 2008/09 FC Porto 09.08.2009 FC Porto 2-0 FC Paços Ferreira Municipal de Aveiro 2007/08 Sporting CP 16.08.2008 FC Porto 0-2 Sporting CP Estádio Algarve 2006/07 Sporting CP 11.08.2007 FC Porto 0-1 Sporting CP Municipal de Leiria 2005/06 FC Porto 19.08.2006 FC Porto 3-0 Vitória FC Municipal de Leiria 2004/05 SL Benfica 13.08.2005 SL Benfica 1-0 Vitória FC Estádio Algarve 2003/04 FC Porto 20.08.2004 FC Porto 1-0 SL Benfica Cidade de Coimbra 2002/03 FC Porto 10.08.2003 FC Porto 1-0 UD Leiria D. Afonso Henriques, Guimarães 2001/02 Sporting CP 18.08.2002 Sporting CP 5-1 Leixões Estádio do Bonfim, Setúbal 2000/01 FC Porto 04.08.2001 Boavista FC 0-1 FC Porto Rio Ave FC, Vila do Conde 13.08.2000 FC Porto 1-1 Sporting CP Estádio das Antas, Porto 1999/00 Sporting CP 31.01.2001 Sporting CP 0-0 FC Porto Estádio de Alvalade, Lisboa 16.05.2001 FC Porto 0-1 Sporting CP Municipal de Coimbra 07.08.1999 SC Beira-Mar 1-2 FC Porto Estádio Mário Duarte, Aveiro 1998/99 FC Porto 15.08.1999 FC Porto 3-1 SC Beira-Mar Estádio das Antas, Porto 08.08.1998 FC Porto 1-0 SC Braga Estádio das Antas, Porto 1997/98 FC Porto 09.09.1998 SC Braga 1-1 FC Porto Estádio 1º Maio, Braga 15.08.1997 Boavista FC 2-0 FC Porto Estádio do Bessa, Porto 1996/97 Boavista FC 10.09.1997