By Carl Spaeth Submitted to the Graduate Degree Program in Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tenor Saxophone Mouthpiece When

MAY 2014 U.K. £3.50 DOWNBEAT.COM MAY 2014 VOLUME 81 / NUMBER 5 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Associate Editor Davis Inman Contributing Editors Ed Enright Kathleen Costanza Art Director LoriAnne Nelson Contributing Designer Ara Tirado Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Sue Mahal Circulation Assistant Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Pete Fenech 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. Jackson, Jimmy Katz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Richard Seidel, Tom Staudter, -

A Tribute to Dave Valentin & the Debut of Bill O'connell's (A.C.E.) Afro

Press contact: John MacElwee - 718-518-6539, [email protected] Tom Pryor - 718-753-3321 [email protected] Hostos Center for the Arts & Culture presents A Tribute to Dave Valentin & the Debut of Bill O’Connell’s (A.C.E.) Afro-Caribbean Ensemble Saturday, April 6, 2019, 7:30 PM LINK TO HIGH RESOLUTION PHOTOS (Bronx, NY) – On Saturday, April 6, Hostos Center for the Arts & Culture presents a double bill of Latin jazz with a Tribute to Dave Valentin, featuring a quintet led by the late flutist’s musical director, pianist Bill O’Connell with virtuoso flutist Andrea Brachfeld, then following with the debut of Bill O’Connell’s most recent project A.C.E. (Afro-Caribbean Ensemble) featuring a nonet comprised of some of New York’s top jazz and Latin jazz artists. The concert will be in the Repertory Theater at Hostos Community College, beginning at 7:30 PM. Tickets are $20, with student tickets at $5, and can be purchased online at www.hostoscenter.org or by calling (718) 518-4455. The box office is open Monday to Friday, 1 PM to 4 PM and will be open two hours prior to performance. In addition to O’Connell, the quintet includes original Dave Valentin Quartet members -- bassist Lincoln Goines and drummer Robby Ameen. Percussionist Román Díaz has been added to the group, and in the title role will be flutist Andrea Brachfeld, well-known for her musical abilities in jazz and Latin Jazz. Valentin said of Brachfeld, “with all due respect, she plays her buns off; one of the first ladies to disprove the concept that only men can deal with the real deal…” The original quartet with Brachfeld have performed tributes to Valentin in different venues in New York and repeat engagements at the Blue Note in Tokyo. -

V.I.E.W. Video & Arkadia Entertainment

EffectiveEFFECTIVE September AUGUST, 1, 20102011 PRICE SCHEDULE V.I.E.W. Video & Arkadia Entertainment Distributed by V.I.E.W., Inc. (Distribution) 11 Reservoir Road, Saugerties, NY 12477 • phone 845-246-9955 • fax 845-246-9966 E-mail: [email protected] • www.view.com TOLL-FREE ORDER DESK 800-843-9843 BILL TO SHIP TO (if different) (no P.O. boxes) NAME NAME ADDRESS ADDRESS CITY STATE ZIP CITY STATE ZIP PHONE COUNTRY PHONE COUNTRY EMAIL OVERSEAS: TOTAL NUMBER ITEMS AMOUNT $ WE CHARGE ACTUAL SHIPPING; How did you hear of us? LESS APPLICABLE DISCOUNT PLEASE INDICATE ❑ AIR SUB-TOTAL METHOD OF PAYMENT ❍ CHECK ❍ MONEY ORDER AMOUNT $ ❑ GROUND ❑ OTHER ❍ VISA ❍ MASTER CARD ❍ AMEX NYS RESIDENTS ADD 8.625% SHIPPING & HANDLING ACCOUNT NUMBER EXP. DATE SECURITY CODE $3.95 FIRST ITEM, $1 EACH ADDITIONAL CARDHOLDER’S NAME (PLEASE PRINT) OVERNIGHT & 2ND DAY AT COST TOTAL CARDHOLDER’S SIGNATURE FOR LIFETIME PUBLIC PERFORMANCE RIGHTS ADD $30 PER TITLE TO THE LIST PRICE. NOTE: Items in bold indicate our most recent releases. ARKADIAARKADIA PROMOTIONAL PROMOTIONAL MATERIAL MATERIAL Visit our Business-To-Business Resource Center at ___ 79001 602267900125602267900125 ArkadiaArkadia Cap BLACKBLACK $10$10 Visit our Business-To-Businesswww.viewb2bonline.com Resource Center at ___ 79002 602267900224 Arkadia Cap WHITE $10 www.viewb2b.com ___ 79002 602267900224 Arkadia Cap WHITE $10 • High & Low Resolution Photos of all front and back covers ___ 79003 602267900323 Arkadia T-shirt BLACK LG $12 • Over 25 Genre Specific Sell-Sheets with a box to insert your name ___ -

QUASIMODE: Ike QUEBEC

This discography is automatically generated by The JazzOmat Database System written by Thomas Wagner For private use only! ------------------------------------------ QUASIMODE: "Oneself-Likeness" Yusuke Hirado -p,el p; Kazuhiro Sunaga -b; Takashi Okutsu -d; Takahiro Matsuoka -perc; Mamoru Yonemura -ts; Mitshuharu Fukuyama -tp; Yoshio Iwamoto -ts; Tomoyoshi Nakamura -ss; Yoshiyuki Takuma -vib; recorded 2005 to 2006 in Japan 99555 DOWN IN THE VILLAGE 6.30 99556 GIANT BLACK SHADOW 5.39 99557 1000 DAY SPIRIT 7.02 99558 LUCKY LUCIANO 7.15 99559 IPE AMARELO 6.46 99560 SKELETON COAST 6.34 99561 FEELIN' GREEN 5.33 99562 ONESELF-LIKENESS 5.58 99563 GET THE FACT - OUTRO 1.48 ------------------------------------------ Ike QUEBEC: "The Complete Blue Note Forties Recordings (Mosaic 107)" Ike Quebec -ts; Roger Ramirez -p; Tiny Grimes -g; Milt Hinton -b; J.C. Heard -d; recorded July 18, 1944 in New York 34147 TINY'S EXERCISE 3.35 Blue Note 6507 37805 BLUE HARLEM 4.33 Blue Note 37 37806 INDIANA 3.55 Blue Note 38 39479 SHE'S FUNNY THAT WAY 4.22 --- 39480 INDIANA 3.53 Blue Note 6507 39481 BLUE HARLEM 4.42 Blue Note 544 40053 TINY'S EXERCISE 3.36 Blue Note 37 Jonah Jones -tp; Tyree Glenn -tb; Ike Quebec -ts; Roger Ramirez -p; Tiny Grimes -g; Oscar Pettiford -b; J.C. Heard -d; recorded September 25, 1944 in New York 37810 IF I HAD YOU 3.21 Blue Note 510 37812 MAD ABOUT YOU 4.11 Blue Note 42 39482 HARD TACK 3.00 Blue Note 510 39483 --- 3.00 prev. unissued 39484 FACIN' THE FACE 3.48 --- 39485 --- 4.08 Blue Note 42 Ike Quebec -ts; Napoleon Allen -g; Dave Rivera -p; Milt Hinton -b; J.C. -

Hybridity and Identity in the Pan-American Jazz Piano Tradition

Hybridity and Identity in the Pan-American Jazz Piano Tradition by William D. Scott Bachelor of Arts, Central Michigan University, 2011 Master of Music, University of Michigan, 2013 Master of Arts, University of Michigan, 2015 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2019 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by William D. Scott It was defended on March 28, 2019 and approved by Mark A. Clague, PhD, Department of Music James P. Cassaro, MA, Department of Music Aaron J. Johnson, PhD, Department of Music Dissertation Advisor: Michael C. Heller, PhD, Department of Music ii Copyright © by William D. Scott 2019 iii Michael C. Heller, PhD Hybridity and Identity in the Pan-American Jazz Piano Tradition William D. Scott, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2019 The term Latin jazz has often been employed by record labels, critics, and musicians alike to denote idioms ranging from Afro-Cuban music, to Brazilian samba and bossa nova, and more broadly to Latin American fusions with jazz. While many of these genres have coexisted under the Latin jazz heading in one manifestation or another, Panamanian pianist Danilo Pérez uses the expression “Pan-American jazz” to account for both the Afro-Cuban jazz tradition and non-Cuban Latin American fusions with jazz. Throughout this dissertation, I unpack the notion of Pan-American jazz from a variety of theoretical perspectives including Latinx identity discourse, transcription and musical analysis, and hybridity theory. -

January 1988

VOLUME 12, NUMBER 1, ISSUE 99 Cover Photo by Lissa Wales Wales PHIL GOULD Lissa In addition to drumming with Level 42, Phil Gould also is a by songwriter and lyricist for the group, which helps him fit his drums into the total picture. Photo by Simon Goodwin 16 RICHIE MORALES After paying years of dues with such artists as Herbie Mann, Ray Barretto, Gato Barbieri, and the Brecker Bros., Richie Morales is getting wide exposure with Spyro Gyra. by Jeff Potter 22 CHICK WEBB Although he died at the age of 33, Chick Webb had a lasting impact on jazz drumming, and was idolized by such notables as Gene Krupa and Buddy Rich. by Burt Korall 26 PERSONAL RELATIONSHIPS The many demands of a music career can interfere with a marriage or relationship. We spoke to several couples, including Steve and Susan Smith, Rod and Michele Morgenstein, and Tris and Celia Imboden, to find out what makes their relationships work. by Robyn Flans 30 MD TRIVIA CONTEST Win a Yamaha drumkit. 36 EDUCATION DRIVER'S SEAT by Rick Mattingly, Bob Saydlowski, Jr., and Rick Van Horn IN THE STUDIO Matching Drum Sounds To Big Band 122 Studio-Ready Drums Figures by Ed Shaughnessy 100 ELECTRONIC REVIEW by Craig Krampf 38 Dynacord P-20 Digital MIDI Drumkit TRACKING ROCK CHARTS by Bob Saydlowski, Jr. 126 Beware Of The Simple Drum Chart Steve Smith: "Lovin", Touchin', by Hank Jaramillo 42 Squeezin' " NEW AND NOTABLE 132 JAZZ DRUMMERS' WORKSHOP by Michael Lawson 102 PROFILES Meeting A Piece Of Music For The TIMP TALK First Time Dialogue For Timpani And Drumset FROM THE PAST by Peter Erskine 60 by Vic Firth 104 England's Phil Seamen THE MACHINE SHOP by Simon Goodwin 44 The Funk Machine SOUTH OF THE BORDER by Clive Brooks 66 The Merengue PORTRAITS 108 ROCK 'N' JAZZ CLINIC by John Santos Portinho A Little Can Go Long Way CONCEPTS by Carl Stormer 68 by Rod Morgenstein 80 Confidence 116 NEWS by Roy Burns LISTENER'S GUIDE UPDATE 6 Buddy Rich CLUB SCENE INDUSTRY HAPPENINGS 128 by Mark Gauthier 82 Periodic Checkups 118 MASTER CLASS by Rick Van Horn REVIEWS Portraits In Rhythm: Etude #10 ON TAPE 62 by Anthony J. -

Paul Haar, DMA 205 Westbrook Music Building 7611 Wren Court the University of Nebraska-Lincoln Lincoln, NE

Page 1 Paul Haar, DMA 205 Westbrook Music Building 7611 Wren Court The University of Nebraska-Lincoln Lincoln, NE. 68506 Lincoln, NE. 68588-0100 (402) 327-9620 (402) 472-5672 (402) 202-6792 (mobile) [email protected] [email protected] www.paulhaarmusic.com Current Position: 2019-Present Associate Professor of Saxophone Direct all aspect of the applied saxophone studio at the UNL Glenn Korff School of Music. This includes applied instruction for 16-22 majors (undergrad, MM and DMA), Directing the UNL Saxophone Choir, Korff Ensemble, and UNL Jazz Saxophone Ensemble. Coaching 4-5 saxophone quartets. 2004-2019 Associate Professor of Saxophone and Director of Jazz Studies The University of Nebraska-Lincoln Recruit and teach applied saxophone students at the undergraduate and graduate levels, teach studio related ensembles, direct UNL Jazz Ensemble I and coordinate all activities related to the UNL jazz program. 2017-Present Founder/Editor-In-Chief of “The Saxophonist” Magazine. An online publication promoting the advocacy of the saxophone, with over 14,814 unique vistors/readers in 35 counties. This also includes an editorial staff, blind peer review panel and 10 (to date) outside authors/contributors. Responsible for editing, content management, reviews and a contributing author. 2017-Present Soprano Saxophonist, TCB Saxophone Quartet Baritone/Tenor Saxophonist, Education: Doctor of Musical Arts-Saxophone Performance with an emphasis in Jazz Studies, The University of Texas at Austin, 2004 ▪Treatise Title: “Jazz Influence Upon Edison Denisov’s -

Wind Band Classics

572129 bk Wild Nights US 2/2/09 10:59 Page 8 Also available: WIND BAND CLASSICS WILD NIGHTS! Frank Ticheli • David Dzubay • Steven Bryant Roshanne Etezady • John Mackey Vince Gnojek, Soprano Saxophone University of Kansas Wind Ensemble • Scott Weiss 8.570074 8.572129 8 572129 bk Wild Nights US 2/2/09 10:59 Page 2 Wild Nights! PICCOLO CLARINET TRUMPET TROMBONE TIMPANI Frank Ticheli • David Dzubay • Steven Bryant • Roshanne Etezady • John Mackey Ann Armstrong* Pete Henry* William Munoz* Frank Perez* Greg Haynes* Larkin Sanders Orlando Ruiz Brett Bohmann Frank Ticheli (b. 1958) David Dzubay (b. 1964) FLUTE Mike Gersten Emily Seifert Stuart Becker PERCUSSION Laura Marsh* Mike Fessenger James Henry Marie Byleen- Cory Hills* Frank Ticheli joined the faculty of the University of David Dzubay is currently Professor of Music, Chair of Alyssa Boone Diana Kaepplinger Patrick Higley Miguel Rivera Southern California’s Thornton School of Music, where the Composition Department, and Director of the New Julia Snell Kayla Slovak Hunninghake Julie Wilder Paul Shapker he is Professor of Composition, in 1991. He is well Music Ensemble at the Indiana University Jacobs Emma Casey Hannah Wagner Evan Hunter Nick Mallin known for his works for concert band, many of which School of Music in Bloomington. He was previously on Ali Rehak Elizabeth Moultan EUPHONIUM Calvin Dugan have become standards in the repertoire. In addition to the faculty of the University of North Texas in Denton. Quin Jackson FRENCH HORN Dan Freeman* composing, he has appeared as guest conductor of his Dzubay has conducted at the Tanglewood, Aspen, and OBOE Steven Elliott Allison Akins* PIANO music at Carnegie Hall, at many American universities June in Buffalo festivals. -

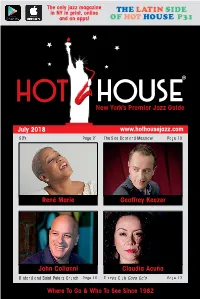

July 2018 92Y Page 21 the Side Door and Mezzrow Page 10

193398_HH_July_0 6/25/18 12:30 PM Page 1 DE The only jazz magazine THE LATIN SIDE in NY in print, online P32 and on apps! OF HOT HOUSE P31 July 2018 www.hothousejazz.com 92Y Page 21 The Side Door and Mezzrow Page 10 René Marie Geoffrey Keezer John Colianni Claudia Acuña Birdand and Saint Peter's Church Page 10 Dizzy's Club Coca-Cola Page 17 Where To Go & Who To See Since 1982 193398_HH_July_0 6/25/18 12:30 PM Page 2 2 193398_HH_July_0 6/25/18 12:30 PM Page 3 3 193398_HH_July_0 6/25/18 12:30 PM Page 4 4 193398_HH_July_0 6/25/18 12:30 PM Page 5 5 193398_HH_July_0 6/25/18 12:30 PM Page 6 6 193398_HH_July_0 6/25/18 12:30 PM Page 7 7 193398_HH_July_0 6/25/18 12:30 PM Page 8 8 193398_HH_July_0 6/25/18 12:30 PM Page 9 9 193398_HH_July_0 6/25/18 12:30 PM Page 10 WINNING SPINS By George Kanzler WO PIANISTS IN THE PRIME OF time suspending style of the late Shirley their careers bring fresh ideas to their Horn. Tlatest albums, featured in this Winning Gillian delivers her own lyrics on the Spins. Both reach beyond the usual piano pair's collaborative song, "You Stay with trio format—one by collaborating with a Me," and reveals her prowess as a scat vocalist on half the tracks, the other by set- singer on the bubbly "Guanajuato," anoth- ting his piano in the context of a swinging er collaboration with improvised sextet. -

3 Big Bandová Angažmá Boba Mintzera

JANÁČKOVA AKADEMIE MÚZICKÝCH UMĚNÍ V BRNĚ Hudební fakulta Katedra jazzové interpretace Saxofon Název práce Big bandová angažmá Boba Mintzera a jejich vliv na umělcovu vlastní tvorbu. Autor práce: Ivan Podhola Vedoucí práce: MgA. Rostislav Fraš Oponent práce: MgA. Radim Hanousek Brno 2017 Podhola Ivan. Big bandová angažmá Boba Mintzera a jejich vliv na umělcovu vlastní tvorbu. Bob Mintzer big bands residency and it´s influences on the artist´s own work. Brno: Janáčkova akademie múzických umění v Brně, Hudební fakulta, Katedra jazzové interpretace, rok 2017, vedoucí bakalářské práce MgA. Rostislav Fraš. Anotace Bakalářská práce Big bandová angažmá Boba Mintzera a jejich vliv na umělcovu vlastní tvorbu pojednává o interpretačním a kompozičním vývoji Boba Mintzera v průběhu jeho působení v big bandech. Annotation The Bachelor´s work Bob Mintzer big bands residency and it´s influences on the artist´s own work deals with the interpretative and compositional progress of Bob Mintzer during his big bands residencies. Klíčová slova Bob Mintzer, big band, improvizace, Buddy Rich, Mel Lewis Keywords Bob Mintzer, big band, improvization, Buddy Rich, Mel Lewis Prohlášení Prohlašuji, že jsem předkládanou práci zpracoval samostatně a použil jen uvedené prameny a literaturu. V Brně, dne 10. května 2017 Ivan Podhola Poděkování Rád bych na tomto místě poděkoval mým učitelům MgA. Rostislavu Frašovi a Mgr. Janu Přibilovi za odborné konzultace a rady, které mi dávali v průběhu zpracovávání této bakalářské práce. Dále bych rád poděkoval mé rodině, která mi byla vždy velkou oporou. Rád bych na tomto místě poděkoval i svým spolužákům, se kterými jsme si užili spoustu skvělých okamžiků, a to jak hudebních, tak i při studiu na této vysoké škole. -

Jazz Faculty and Friends: an Evening of Great Music

Kennesaw State University Upcoming Music Events Tuesday, November 18 Kennesaw State University Jazz Combos 8:00 pm • Bailey Performance Center Performance Hall School of Music Wednesday, November 19 Kennesaw State University Wind Ensemble and Concert Band presents 8:00 pm • Bailey Performance Center Performance Hall Thursday, November 20 Kennesaw State University Gospel Choir 8:00 pm • Bailey Performance Center Performance Hall Kennesaw State University Saturday, November 22 Kennesaw State University Jazz Faculty and Friends Opera Gala 8:00 pm • Bailey Performance Center Performance Hall Monday, November 24 Kennesaw State University Percussion Ensemble 8:00 pm • Bailey Performance Center Performance Hall Tuesday, December 2 Kennesaw State University Choral Ensembles Holiday Concert 8:00 pm • Bailey Performance Center Performance Hall Monday, November 17, 2008 8:00 pm Dr. Bobbie Bailey & Family Performance Center Concert Hall For the most current information, please visit http://www.kennesaw.edu/arts/events/ Twenty-third Concert of the 2008-2009 season Kennesaw State University Justin Varnes drums School of Music Born in Jacksonville, Florida, Justin Varnes studied music at the Monday, November 17, 2008 University of North Florida. After a brief stint with the Noel Freidline 8:00 pm Quintet, Mr. Varnes relocated to New York City to pursue a master's Dr. Bobbie Bailey & Family Performance Center degree in jazz studies at the New School. In New York, Justin toured for six years with vocalist Phoebe Snow, with whom he performed on the Performance Hall Roseanne Barr Show, as well as National Public Radio's "World Cafe" (he would later perform on "World Cafe" with pop group "Five for Fighting"). -

Guest Artists 2009-10 : School of Music : Texas State University

School of Music Guest Artists 2009-10 Texas State School of Music maintains a faculty of 70 outstanding musicians/scholars/teachers. That makes it an extraordinary bonus that so many leading professionals come to the campus each year to add to the artistic mix, giving guest recitals, master classes, and lectures. Below is just a sample of this amazing array of expert guests. 2009-2010 Dr. David Littrell guest clinician with Symphony Orchestra Monday, January 25, 2010, 2:00-4:00 pm in MUS 224 Served as national President of the American String Teachers Association in 2002-2004. conducts the University Orchestra and teaches strings at Kansas State University conducts the “Gold Orchestra”, 58 Manhattan KS area string students in grades 5-10. The “Gold Orchestra” toured England in 1997, Seattle and British Columbia in 1999, and performed at Carnegie Hall in 2001 and 2006. They performed at the ASTA National Orchestra Festival in Dallas in March 2004. served six years as Editor of the Books and Music Reviews section of the American String Teacher; editor of ASTA’s two-volume String Syllabus Dr. David Littrell Editor and Compiler of GIA Publications’ two volumes of Teaching Music through Performance in Orchestra Bob Mintzer Bob Mintzer debuts and performs a new Big Band composition commissioned by Texas State Jazz for the Hill Country Jazz Festival Saturday, February 6. Bob also appears as guest artist with the Hehmsoth Project at the Elephant Jazz Club, Austin, Friday, February 5, 9:30PM. In the jazz world Bob Mintzer is a household name, usually associated with being a saxophonist, bass clarinetist, composer, arranger, leader of a Grammy winning big band, member of the Yellowjackets, and educator.