Sculpting in Time: Reflections on the Cinema

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

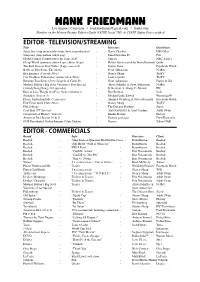

Hank Friedmann CV

HANK FRIEDMANN Los Angeles, California • [email protected] • hankf.com Member of the Motion Picture Editors Guild (IATSE Local 700) & CSATF Safety Pass certified ____________________________________________________________________________ EDITOR - TELEVISION/STREAMING Title Directors Distributor Santa, Inc (stop motion television show, in production) - Harry Chaskin HBO Max Simpsons (stop motion couch gag) - John Harvatine IV Fox Global Citizen Countdown to the Prize 2020 - Various NBC & Int’l Gloop World (animatic editor 5 eps, editor 15 eps) - Helder Sun (created by Justin Roiland) Quibi The Real Bros of Simi Valley (5 eps, season 3) - Jimmy Tatro Facebook Watch Between Two Ferns: The Movie - Scott Aukerman Netflix Blackspiracy (Comedy Pilot) - Stoney Sharp TruTV Can You Beat Yamaneika? (Game Show Pilot) - Lauren Quinn TruTV Between Two Ferns (Jerry Seinfeld & Cardi B.) - Scott Aukerman Funny or Die Michael Bolton’s Big Sexy Valentine’s Day Special - Akiva Schaffer & Scott Aukerman Netflix Comedy Bang Bang (110 episodes) - B. Berman, S. Sharp, D. Jelinek IFC How to Lose Weight in 4 Easy Steps (Sundance) - Ben Berman Jash Snatchers (Season 3) - Michael Lukk Litwak Warner/go90 Please Understand Me (5 episodes) - Ahamed Weinberg & Steven Feinartz Facebook Watch End Times Girls Club (Pilot) - Stoney Sharp TruTV Flulanthropy - The Director Brothers Seeso Cool Dad (TV Special) - Alex Kavutskiy & Ariel Gardner Adult Swim Crossroads of History “Lincoln” - Marko Slavnic History American Idol Season 10 & 11 - Remote packages Ford/Fremantle GOP Presidential Online Internet Cyber Debate - Various Yahoo!/FoD ____________________________________________________________________________ EDITOR - COMMERCIALS Brand Info Directors Client Reebok - Allen Iverson/Question Mid Double Cross - Roundhouse Reebok Reebok - Gigi Hadid “Wild is Wherever” - Roundhouse Reebok Reebok - FW19 Trail - Roundhouse Reebok Reebok - “Cardi B: Aztrek” - Eric Notarnicola Reebok Reebok - “Cardi B vs. -

Telecom Regulatory Authority of India (IS/ISO 9001: 2015 Cer�fied Organisa�On)

Telecom Regulatory Authority of India (IS/ISO 9001: 2015 Cerfied Organisaon) Annual Report 2017-18 Mahanagar Doorsanchar Bhawan, Jawahar Lal Nehru Marg, (Old Minto Road), New Delhi-110002 Telephone : +91-11-23664147 Fax No:+91-11-23211046 Website:hp://www.trai.gov.in LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL To the Central Government through Hon’ble Minister of Communicaons and Informaon Technology It is my privilege to forward the 21st Annual Report for the year 2017-18 of the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India to be laid before both Houses of Parliament. Included in this Report is the informaon required to be forwarded to the Central Government under the provisions of the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India Act, 1997, as amended by TRAI (Amendment) Act, 2000. The Report contains an overview of the telecom and broadcasng sectors and a summary of the key iniaves of TRAI on regulatory maers with specific reference to the funcons mandated to it under the Act. The Audited Annual Statement of Accounts of TRAI is also included in the Report. (RAM SEWAK SHARMA) CHAIRPERSON Dated: September 2018 III TABLE OF CONTENTS Sl.No. Parculars Page Nos. Overview of the Telecom and Broadcasng Sectors 1-8 Policies and Programmes 9-60 A. Review of General Environment in the Telecom Sector Part – I B. Review of Policies and Programmes C. Annexures to Part – I Part – II Review of working and operaon of the Telecom 61-130 Regulatory Authority of India Part – III Funcons of Telecom Regulatory Authority of India in respect of maers 131-150 specified in Secon 11 of Telecom Regulatory Authority of India Act Part – IV Organizaonal maers of Telecom Regulatory Authority of India and 151-220 Financial performance A. -

World Book Night 2016 | University of Essex

09/29/21 World Book Night 2016 | University of Essex World Book Night 2016 View Online A list of books you might like to try reading for fun - they're all in stock at the Albert Sloman Library! 197 items General Fiction (48 items) Contemporary authors (18 items) Life after life - Kate Atkinson, 2013 Book | Costa Book Award winner 2013. "During a snowstorm in England in 1910, a baby is born and dies before she can take her first breath. During a snowstorm in England in 1910, the same baby is born and lives to tell the tale. What if there were second chances? And third chances? In fact an infinite number of chances to live your life? Would you eventually be able to save the world from its own inevitable destiny? And would you even want to? Life After Life follows Ursula Todd as she lives through the turbulent events of the last century again and again. With wit and compassion, Kate Atkinson finds warmth even in life’s bleakest moments, and shows an extraordinary ability to evoke the past. Here she is at her most profound and inventive, in a novel that celebrates the best and worst of ourselves." (Review/summary from Amazon) House of leaves - Mark Z. Danielewski, 2001 Book | Horror/Romance/Postmodern. "Johnny Truant, a wild and troubled sometime employee in a LA tattoo parlour, finds a notebook kept by Zampano', a reclusive old man found dead in a cluttered apartment. Herein is the heavily annotated story of the Navidson Report. Will Navidson, a photojournalist, and his family move into a new house. -

Film Film Film Film

Annette Michelson’s contribution to art and film criticism over the last three decades has been un- paralleled. This volume honors Michelson’s unique C AMERA OBSCURA, CAMERA LUCIDA ALLEN AND TURVEY [EDS.] LUCIDA CAMERA OBSCURA, AMERA legacy with original essays by some of the many film FILM FILM scholars influenced by her work. Some continue her efforts to develop historical and theoretical frame- CULTURE CULTURE works for understanding modernist art, while others IN TRANSITION IN TRANSITION practice her form of interdisciplinary scholarship in relation to avant-garde and modernist film. The intro- duction investigates and evaluates Michelson’s work itself. All in some way pay homage to her extraordi- nary contribution and demonstrate its continued cen- trality to the field of art and film criticism. Richard Allen is Associ- ate Professor of Cinema Studies at New York Uni- versity. Malcolm Turvey teaches Film History at Sarah Lawrence College. They recently collaborated in editing Wittgenstein, Theory and the Arts (Lon- don: Routledge, 2001). CAMERA OBSCURA CAMERA LUCIDA ISBN 90-5356-494-2 Essays in Honor of Annette Michelson EDITED BY RICHARD ALLEN 9 789053 564943 MALCOLM TURVEY Amsterdam University Press Amsterdam University Press WWW.AUP.NL Camera Obscura, Camera Lucida Camera Obscura, Camera Lucida: Essays in Honor of Annette Michelson Edited by Richard Allen and Malcolm Turvey Amsterdam University Press Front cover illustration: 2001: A Space Odyssey. Courtesy of Photofest Cover design: Kok Korpershoek, Amsterdam Lay-out: japes, Amsterdam isbn 90 5356 494 2 (paperback) nur 652 © Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam, 2003 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, me- chanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permis- sion of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. -

Exposing Corruption in Progressive Rock: a Semiotic Analysis of Gentle Giant’S the Power and the Glory

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Music Music 2019 EXPOSING CORRUPTION IN PROGRESSIVE ROCK: A SEMIOTIC ANALYSIS OF GENTLE GIANT’S THE POWER AND THE GLORY Robert Jacob Sivy University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/etd.2019.459 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Sivy, Robert Jacob, "EXPOSING CORRUPTION IN PROGRESSIVE ROCK: A SEMIOTIC ANALYSIS OF GENTLE GIANT’S THE POWER AND THE GLORY" (2019). Theses and Dissertations--Music. 149. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/music_etds/149 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Music by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

The Stelliferous Fold : Toward a Virtual Law of Literature’S Self- Formation / Rodolphe Gasche´.—1St Ed

T he S telliferous Fold he Stelliferous Fold Toward a V irtual L aw of TL iterature’ s S elf-Formation R odolphe G asche´ fordham university press New York 2011 Copyright ᭧ 2011 Fordham University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any other—except for brief quotations in printed reviews, without the prior permission of the publisher. Fordham University Press has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of URLs for external or third-party Internet websites referred to in this publication and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate. Fordham University Press also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Gasche´, Rodolphe. The stelliferous fold : toward a virtual law of literature’s self- formation / Rodolphe Gasche´.—1st ed. p. cm. Includes index. ISBN 978-0-8232-3434-9 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-8232-3435-6 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-8232-3436-3 (ebk.) 1. Literature—Philosophy. 2. Literature—History and criticism—Theory, etc.I. Title. PN45.G326 2011 801—dc22 2011009669 Printed in the United States of America 131211 54321 First edition For Bronia Karst and Alexandra Gasche´ contents Acknowledgments ix Introduction 1 Part I. Scenarios for a Theory 1. Un-Staging the Beginning: Herman Melville’s Cetology 27 2. -

Full Cinematic Retrospective of Director Andrei Tarkovsky This Summer at MAD

Full Cinematic Retrospective of Director Andrei Tarkovsky this Summer at MAD Andrei Tarkovsky, Sculpting in Time presents the work of the revolutionary director and includes screenings—all on 35 mm—of all seven feature films and a behind-the-scenes documentary Stalker, 1976. Andrei Tarkovsky. New York, NY (June 8, 2015)—The Museum of Arts and Design presents a full cinematic retrospective of Andrei Tarkovsky’s work this summer with its latest cinema series, Andrei Tarkovsky, Sculpting in Time, from July 10 through August 28, 2015. Over the course of just seven feature films, Tarkovsky produced a poetic and enigmatic body of work that expanded the possibilities of cinema as an art form and transformed a wide range of genres including science fiction, war stories, film essays and historical dramas. Celebrating the legacy of this revolutionary director, the retrospective includes screenings of Tarkovsky’s seven feature films on 35 mm, as well as a behind-the-scenes documentary that reveals the process behind his groundbreaking practice and cinematic achievements. “Few directors have had as large of an influence on cinema as Andrei Tarkovsky,” says Jake Yuzna, MAD’s Director of Public Programs. “Working under censorship and with little support from the Soviet Union, Tarkovsky fought fiercely for his conceptualization of cinema as a singular and vital art form. Reconsidering the role of films in an age of increasing technology, Tarkovsky saw cinema as not merely a tool for communicating information, but as ‘a moral barometer in a sea of competing narratives.’” 2 COLUMBUS CIRCLE NEW YORK, NEW YORK 10019 P 212.299.7777 F 212.299.7701 MADMUSEUM.ORG Premiering on July 10 with Tarkovsky’s science fiction classic, Solaris, the retrospective showcases the director’s distinctive and influential aesthetic, characterized by expressive, sweeping takes, the evocative use of landscapes, and his method of “sculpting in time” with a camera. -

Songs of the Century

Songs of the Century T. Austin Graham hat is the time, the season, the historical context of a popular song? When is it most present in the world, best able Wto reflect, participate in, or construct some larger social reality? This essay will consider a few possible answers, exploring the ways that a song can exist in something as brief as a passing moment and as broad as a century. It will also suggest that when we hear those songs whose times have been the longest, we might not be hearing “songs” at all. Most people are likely to have an intuitive sense for how a song can contract and swell in history, suited to a certain context but capable of finding any number of others. Consider, for example, the various uses to which Joan Didion is able to put music in her generation-defining essay “Slouching Towards Bethlehem,” a meditation on drifting youth and looming apocalypse in the days of the Haight-Ashbury counterculture. Songs create a powerful sense of time and place throughout the piece, with Didion nodding to the Grateful Dead, Jefferson Airplane, Quick- silver Messenger Service, and “No Milk Today” by Herman’s Hermits, “a song I heard every morning in the cold late spring of 1967 on KRFC, the Flower Power Station, San Francisco.”1 But the music that speaks most directly and reverberates most widely in the essay is “For What It’s Worth,” the Buffalo Springfield single whose chiming guitar fifths and famous chorus—“Stop, hey, what’s that sound / Everybody look what’s going down”—make it instantly recognizable nearly five decades later.2 To listen to “For What It’s Worth” on Didion’s pages is to hear a song that exists in many registers and seems able to suffuse everything, from a snatch of conversation, to a set of political convictions, to nothing less than “The ’60s” itself. -

Tarkovsky Is for Me the Greatest, the One Who Invented a New Language, True to the Nature of Film As It Captures Life As a Reflection, Life As a Dream.”

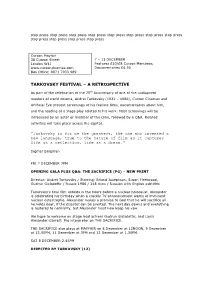

stop press stop press stop press stop press stop press stop press stop press stop press stop press stop press stop press stop press Curzon Mayfair 38 Curzon Street 7 – 13 DECEMBER London W1J Features £10/£8 Curzon Members; www.curzoncinemas.com Documentaries £6.50 Box Office: 0871 7033 989 TARKOVSKY FESTIVAL – A RETROSPECTIVE As part of the celebration of the 75th Anniversary of one of the undisputed masters of world cinema, Andrei Tarkovsky (1932 – 1986), Curzon Cinemas and Artificial Eye present screenings of his feature films, documentaries about him, and the reading of a stage play related to his work. Most screenings will be introduced by an actor or member of the crew, followed by a Q&A. Related activities will take place across the capital. “Tarkovsky is for me the greatest, the one who invented a new language, true to the nature of film as it captures life as a reflection, life as a dream.” Ingmar Bergman FRI 7 DECEMBER 7PM OPENING GALA PLUS Q&A: THE SACRIFICE (PG) – NEW PRINT Director: Andrei Tarkovsky / Starring: Erland Josephson, Susan Fleetwood, Gudrun Gisladottir / Russia 1986 / 148 mins / Russian with English subtitles Tarkovsky's final film unfolds in the hours before a nuclear holocaust. Alexander is celebrating his birthday when a crackly TV announcement warns of imminent nuclear catastrophe. Alexander makes a promise to God that he will sacrifice all he holds dear, if the disaster can be averted. The next day dawns and everything is restored to normality, but Alexander must now keep his vow. We hope to welcome on stage lead actress Gudrun Gisladottir, and Layla Alexander-Garrett, the interpreter on THE SACRIFICE. -

Teaching the Short Story: a Guide to Using Stories from Around the World. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 397 453 CS 215 435 AUTHOR Neumann, Bonnie H., Ed.; McDonnell, Helen M., Ed. TITLE Teaching the Short Story: A Guide to Using Stories from around the World. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-1947-6 PUB DATE 96 NOTE 311p. AVAILABLE FROM National Council of Teachers of English, 1111 W. Kenyon Road, Urbana, IL 61801-1096 (Stock No. 19476: $15.95 members, $21.95 nonmembers). PUB 'TYPE Guides Classroom Use Teaching Guides (For Teacher) (052) Collected Works General (020) Books (010) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC13 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Authors; Higher Education; High Schools; *Literary Criticism; Literary Devices; *Literature Appreciation; Multicultural Education; *Short Stories; *World Literature IDENTIFIERS *Comparative Literature; *Literature in Translation; Response to Literature ABSTRACT An innovative and practical resource for teachers looking to move beyond English and American works, this book explores 175 highly teachable short stories from nearly 50 countries, highlighting the work of recognized authors from practically every continent, authors such as Chinua Achebe, Anita Desai, Nadine Gordimer, Milan Kundera, Isak Dinesen, Octavio Paz, Jorge Amado, and Yukio Mishima. The stories in the book were selected and annotated by experienced teachers, and include information about the author, a synopsis of the story, and comparisons to frequently anthologized stories and readily available literary and artistic works. Also provided are six practical indexes, including those'that help teachers select short stories by title, country of origin, English-languag- source, comparison by themes, or comparison by literary devices. The final index, the cross-reference index, summarizes all the comparative material cited within the book,with the titles of annotated books appearing in capital letters. -

Directing the Narrative Shot Design

DIRECTING THE NARRATIVE and SHOT DESIGN The Art and Craft of Directing by Lubomir Kocka Series in Cinema and Culture © Lubomir Kocka 2018. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Vernon Art and Science Inc. www.vernonpress.com In the Americas: In the rest of the world: Vernon Press Vernon Press 1000 N West Street, C/Sancti Espiritu 17, Suite 1200, Wilmington, Malaga, 29006 Delaware 19801 Spain United States Series in Cinema and Culture Library of Congress Control Number: 2018933406 ISBN: 978-1-62273-288-3 Product and company names mentioned in this work are the trademarks of their respective owners. While every care has been taken in preparing this work, neither the authors nor Vernon Art and Science Inc. may be held responsible for any loss or damage caused or alleged to be caused directly or indirectly by the information contained in it. CONTENTS PREFACE v PART I: DIRECTORIAL CONCEPTS 1 CHAPTER 1: DIRECTOR 1 CHAPTER 2: VISUAL CONCEPT 9 CHAPTER 3: CONCEPT OF VISUAL UNITS 23 CHAPTER 4: MANIPULATING FILM TIME 37 CHAPTER 5: CONTROLLING SPACE 43 CHAPTER 6: BLOCKING STRATEGIES 59 CHAPTER 7: MULTIPLE-CHARACTER SCENE 79 CHAPTER 8: DEMYSTIFYING THE 180-DEGREE RULE – CROSSING THE LINE 91 CHAPTER 9: CONCEPT OF CHARACTER PERSPECTIVE 119 CHAPTER 10: CONCEPT OF STORYTELLER’S PERSPECTIVE 187 CHAPTER 11: EMOTIONAL MANIPULATION/ EMOTIONAL DESIGN 193 CHAPTER 12: PSYCHO-PHYSIOLOGICAL REGULARITIES IN LEFT-RIGHT/RIGHT-LEFT ORIENTATION 199 CHAPTER 13: DIRECTORIAL-DRAMATURGICAL ANALYSIS 229 CHAPTER 14: DIRECTOR’S BOOK 237 CHAPTER 15: PREVISUALIZATION 249 PART II: STUDIOS – DIRECTING EXERCISES 253 CHAPTER 16: I. -

Perception of Aircraft Height and Noise (Imm-15)

Gatwick Airport Arrivals Review: Perception of Aircraft Height and Noise (Imm-15) Main author: Gianluca Memoli (University of Sussex) Key contributions from: Giles Hamilton-Fletcher (University of Sussex) Federigo Ceraudo (University of Sussex) Laimonas Ratkevicius (Environmental Resources Management, data in Chapter 8) Matt Brookes (Helios, data in Chapter 9) Acknowledgements This report responds to recommendation Imm-15 of the Gatwick Independent Arrival Review. This study was run by an independent team of researchers from the University of Sussex, but its costs were covered by Gatwick Airport Ltd., which also deployed four noise measuring units in the areas covered by the social surveys. The authors would like to thank the steering committee – Steve Mitchell (Environmental Resources Management), Colin Grimwood (CJG Environmental Management), Vicki Hughes (Gatwick Airport Ltd), Graham Lake (Noise Management Board), Andy Sinclair (Gatwick Airport Ltd), Brendan Sheil (Gatwick Airport Ltd), Matt Brookes (Helios) – for the support received during the study. This study would not have been possible without the response of the people in the selected communities. They have spent their time answering our questions, plane-spotting and sharing their opinions with us, hoping that this additional information will facilitate discussions with their local airport. Our sincerest thanks go to all participants. Published by: University of Sussex, Brighton, 1/3/2018 ISBN: 978-0-9957862-3-3 Cover image purchased from i-Stock Photo on 28/02/2018. References This study uses the numerical style for references (see http://www.sussex.ac.uk/skillshub/?id=381). This means that citations appear as [number] in the main text: the numbering refers to a list at the end of the document (section 13) Perception of Aircraft Height and Noise Contents Contents Glossary ..................................................................................................................................................