The Filioque Clause in History and Theology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE EUCHARIST in EARLY MEDIEVAL EUROPE Celia

THE EUCHARIST IN EARLY MEDIEVAL EUROPE Celia Chazelle In 843 or 844, Pascasius Radbertus, a monk of the Carolingian royal monastery of Corbie and its abbot from 843 to c. 847, presented King Charles the Bald (d. 877) with a special gift: a treatise about the Eucha- rist that Pascasius had written for Corbie’s mission house of Corvey between 831 and 833.1 Located in the eastern Carolingian territory of Saxony, Corvey had been founded from Corbie in 822 to help cement Christianity, and with it Carolingian rule, among the Saxons whom Charlemagne (d. 814) had forcibly converted from paganism around the turn of the ninth century. Pascasius must have recognized the significance of his gift’s timing, made either at Christmas (843) or at Easter (844).2 One of the key precepts expounded in this work, the first Latin treatise specifically on the Eucharist, is that through the Mass, bread and wine are inwardly, mystically changed into the historical flesh and blood of Christ. The sacrament that the king received in the feast honoring the incarnation (Christmas) or resurrection (Easter) was holy food and drink, the source of eternal salvation, because it contained the very body born of Mary in Bethlehem and crucified in Jerusalem. Pascasius wrote De corpore et sanguine Domini (“On the Lord’s Body and Blood”) in the midst of the rebellion of the three older sons of Emperor Louis the Pious (d. 840). By 843, the civil strife this unleashed had torn the Carolingian Empire apart;3 when Louis’ youngest son, 1 I am very grateful to numerous friends and colleagues for generously sharing their knowledge and offering advice on earlier drafts of this article. -

21.05.30 the Holy Trinity

TRINITY SUNDAY 135 NE Randolph Avenue, Peoria, Illinois 61606 Online: www.trinitypeoria.com ~ (309) 676-4609 The Holy Trinity May 30, 2021 Sunday Worship 8:00, 9:30 and 11:00 a.m. WELCOME IN THE NAME OF OUR RISEN LORD Welcome to Trinity! Today in the Divine Service God proclaims to us through Word and Sacrament the forgiveness, love, and salvation that He has won for us through the death and resurrection of His Son Jesus Christ. LARGE PRINT BULLETINS are available from an usher for persons with vision difficulties. WORSHIPPING WITH OUR CHILDREN This week we celebrate God as the Trinity. The word “Trinity” means “three.” For Christians the word helps us understand that God shows Himself to us as “Father, Son and Holy Spirit.” He is three persons in one God. Only He can do that! It is hard for us to understand exactly how God works but the one thing we know for sure is that God the Father loves us so much that God the Son, Jesus, was sent to give His life to pay for our sins and then rose to life again so that we could live forever. God the Holy Spirit, many times shown as a dove, gives us faith to believe that God loves us this much! See how many triangles you can find in church. Ideas adapted from Kids in the Divine Service by Christopher I. Thoma. ©2000 by the Commission on Worship of The Lutheran Church-Missouri Synod. All rights reserved. Divine Service - Setting Two + We Come Into God’s Presence + In celebration of Trinity Sunday, we will confess the Athanasian Creed separated into four parts throughout our liturgy. -

Augustine and the Art of Ruling in the Carolingian Imperial Period

Augustine and the Art of Ruling in the Carolingian Imperial Period This volume is an investigation of how Augustine was received in the Carolingian period, and the elements of his thought which had an impact on Carolingian ideas of ‘state’, rulership and ethics. It focuses on Alcuin of York and Hincmar of Rheims, authors and political advisers to Charlemagne and to Charles the Bald, respectively. It examines how they used Augustinian political thought and ethics, as manifested in the De civitate Dei, to give more weight to their advice. A comparative approach sheds light on the differences between Charlemagne’s reign and that of his grandson. It scrutinizes Alcuin’s and Hincmar’s discussions of empire, rulership and the moral conduct of political agents during which both drew on the De civitate Dei, although each came away with a different understanding. By means of a philological–historical approach, the book offers a deeper reading and treats the Latin texts as political discourses defined by content and language. Sophia Moesch is currently an SNSF-funded postdoctoral fellow at the University of Oxford, working on a project entitled ‘Developing Principles of Good Govern- ance: Latin and Greek Political Advice during the Carolingian and Macedonian Reforms’. She completed her PhD in History at King’s College London. Augustine and the Art of Ruling in the Carolingian Imperial Period Political Discourse in Alcuin of York and Hincmar of Rheims Sophia Moesch First published 2020 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN and by Routledge 52 Vanderbilt Avenue, New York, NY 10017 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business Published with the support of the Swiss National Science Foundation. -

Continuity and Tradition: the Prominent Role of Cyrillian Christology In

Jacopo Gnisci Jacopo Gnisci CONTINUITY AND TRADITION: THE PROMINENT ROLE OF CYRILLIAN CHRISTOLOGY IN FIFTEENTH AND SIXTEENTH CENTURY ETHIOPIA The Ethiopian Tewahedo Church is one of the oldest in the world. Its clergy maintains that Christianity arrived in the country during the first century AD (Yesehaq 1997: 13), as a result of the conversion of the Ethiopian Eunuch, narrated in the Acts of the Apostles (8:26-39). For most scholars, however, the history of Christianity in the region begins with the conversion of the Aksumite ruler Ezana, approximately during the first half of the fourth century AD.1 For historical and geographical reasons, throughout most of its long history the Ethiopian Church has shared strong ties with Egypt and, in particular, with the Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria. For instance, a conspicuous part of its literary corpus, both canonical and apocryphal, is drawn from Coptic sources (Cerulli 1961 67:70). Its liturgy and theology were also profoundly affected by the developments that took place in Alexandria (Mercer 1970).2 Furthermore, the writings of one of the most influential Alexandrian theologians, Cyril of Alexandria (c. 378-444), played a particularly significant role in shaping Ethiopian theology .3 The purpose of this paper is to highlight the enduring importance and influence of Cyril's thought on certain aspects of Ethiopian Christology from the early developments of Christianity in the country to the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Its aim, therefore, is not to offer a detailed examination of Cyril’s work, or more generally of Ethiopian Christology. Rather, its purpose is to emphasize a substantial continuity in the traditional understanding of the nature of Christ amongst Christian 1 For a more detailed introduction to the history of Ethiopian Christianity, see Kaplan (1982); Munro-Hay (2003). -

5000140104-5000223054-1-Sm

The University of Manchester Research The beginnings of printing in the Ottoman capital Link to publication record in Manchester Research Explorer Citation for published version (APA): Palabiyik, N. (2015). The beginnings of printing in the Ottoman capital. Studies in Ottoman Science, 16(2), 3-32. https://dergipark.org.tr/en/download/article-file/673531 Published in: Studies in Ottoman Science Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on Manchester Research Explorer is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Proof version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Explorer are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Takedown policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please refer to the University of Manchester’s Takedown Procedures [http://man.ac.uk/04Y6Bo] or contact [email protected] providing relevant details, so we can investigate your claim. Download date:04. Oct. 2021 Osmanlı Bilimi Araştırmaları, XVI/2 (2015): 3-32 THE BEGINNINGS OF PRINTING IN THE OTTOMAN CAPITAL: BOOK PRODUCTION AND CIRCULATION IN EARLY MODERN ISTANBUL Nil Pektaş* When Johannes Gutenberg began printing using the technology of movable type in Mainz around 1439, the Western world was to change rapidly and irreversibly. This shift from mainly handwritten production and the less popular xylographic printing (made from a single carved or sculpted block for each page) to typographic printing (made with movable type on a printing press in Gutenberg’s style) made it possible to produce more books by considerably reducing the time and cost of production. -

A Study on Religious Variables Influencing GDP Growth Over Countries

Religion and Economic Development - A study on Religious variables influencing GDP growth over countries Wonsub Eum * University of California, Berkeley Thesis Advisor: Professor Jeremy Magruder April 29, 2011 * I would like to thank Professor Jeremy Magruder for his valuable advice and guidance throughout the paper. I would also like to thank Professor Roger Craine, Professor Sofia Villas-Boas, and Professor Minjung Park for their advice on this research. Any error or mistake is my own. Abstract Religion is a popular topic to be considered as one of the major factors that affect people’s lifestyles. However, religion is one of the social factors that most economists are very careful in stating a connection with economic variables. Among few researchers who are keen to find how religions influence the economic growth, Barro had several publications with individual religious activities or beliefs and Montalvo and Reynal-Querol on religious diversity. In this paper, I challenge their studies by using more recent data, and test whether their arguments hold still for different data over time. In the first part of the paper, I first write down a simple macroeconomics equation from Mankiw, Romer, and Weil (1992) that explains GDP growth with several classical variables. I test Montalvo and Reynal-Querol (2003)’s variables – religious fragmentation and religious polarization – and look at them in their continents. Also, I test whether monthly attendance, beliefs in hell/heaven influence GDP growth, which Barro and McCleary (2003) used. My results demonstrate that the results from Barro’s paper that show a significant correlation between economic growth and religious activities or beliefs may not hold constant for different time period. -

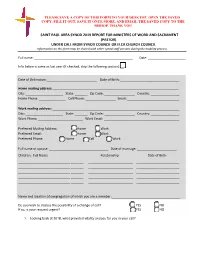

UNDER CALL from SYNOD COUNCIL OR ELCA CHURCH COUNCIL Information on This Form May Be Shared with Other Synod Staff Persons During the Mobility Process

PLEASE SAVE A COPY OF THIS FORM TO YOUR DESKTOP, OPEN THE SAVED COPY, FILL IT OUT, SAVE IT ONCE MORE, AND EMAIL THE SAVED COPY TO THE BISHOP. THANK YOU SAINT PAUL AREA SYNOD 2019 REPORT FOR MINISTERS OF WORD AND SACRAMENT (PASTOR) UNDER CALL FROM SYNOD COUNCIL OR ELCA CHURCH COUNCIL Information on this form may be shared with other synod staff persons during the mobility process Full name: _______________________________________________________ Date: _____________________ Info below is same as last year (if checked, skip the following section):__ Date of Ordination:____________________________ Date of Birth: _________________________________ Home mailing address: ______________________________________________________________________ City: _____________________ State: _______ Zip Code: _________________ Country: ________________ Home Phone: _______________ Cell Phone: _________________ Email: _____________________________ Work mailing address: _______________________________________________________________________ City: _____________________ State: _______ Zip Code: _________________ Country: ________________ Work Phone: _________________________ Work Email: __________________________________________ Preferred Mailing Address: Home Work Preferred Email: Home Work Preferred Phone: Home Cell Work Full name of spouse: _________________________________ Date of marriage: ______________________ Children: Full Name Relationship Date of Birth _____________________________ _______ _________________________ ________________________ _____________________________ -

The Athanasian Creed

The Athanasian Creed So likewise the Father is almighty, For the right faith is that we believe the Son almighty, and the Holy and confess that our Lord Jesus Christianity constantly struggles to keep the Faith free from false Spirit almighty. Christ, the Son of God, philosophies. And yet They are not three is God and man; In Fourth Century Alexandria, Egypt, a persuasive preacher with a logical almighties but One Almighty. God of the substance of the Father, mind used a philosophical concept foreign to the Scriptures in order to explain So the Father is God, the Son is begotten before the worlds; the connection between Jesus and his Father. Arius borrowed from the popular God, and the Holy Spirit is God. and man of the substance of His And yet They are not three mother, born in the world. Greek concept that a “god,” by nature, had to be high, distant and almighty; Gods but one God. Perfect God and perfect man, of a reason- and that humans, consequently, had to be low, spatial and inferior. So likewise the Father is Lord, the able soul and human flesh subsisting. Arius taught that only the Father was really a proper God. Because Jesus Son Lord, and the Holy Spirit Lord. Equal to the Father as touching was human, he was therefore only a creature (created by God) and therefore And yet They are not three His Godhead and inferior to the did not really possess any divine qualities. Lords but One Lord. Father as touching His The problem: when Arius denied the divinity of Christ, he destroyed God’s For as we are compelled by the manhood; role in accomplishing our salvation. -

The Chalcedonian Christology of St John Damascene : Philosophical Terminology and Theological Arguments

Durham E-Theses The Chalcedonian Christology of St John Damascene : philosophical terminology and theological arguments Metallidis, George How to cite: Metallidis, George (2003) The Chalcedonian Christology of St John Damascene : philosophical terminology and theological arguments, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/1085/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 UNIVERSITY OF DURHAM DEPARTMENT OF THEOLOGY GEORGE METALLIDIS The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consentand information derived from it should be acknowledged. The Chalcedonian Christology of St John Damascene: Philosophical Terminology and Theological Arguments PhD Thesis/FourthYear Supervisor: Prof. ANDREW LOUTH 0-I OCT2003 Durham 2003 The ChalcedonianChristology of St John Damascene To my Mother Despoina The ChalcedonianChristology of St John Damascene CONTENTS Page ABBREVIATIONS 7 ACKNOWLEDGMENT 12 INTRODUCTION 14 CHAPTER ONE TheLife of St John Damascene 1. -

How Orthodox Is the Eastern Orthodox Church?

How Orthodox is the Eastern Orthodox Church? Introduction As a result of some questions I thought it wise to give a simple evaluation of the Eastern Orthodox Church (EOC). 1 This is even more relevant since recent decades have seen hordes of evangelicals (especially disaffected Charismatics) relocate into the EOC under the presumption that it has more fundamental historic prestige than modern churches. While in some doctrines the EOC has been a safeguard of apostolic and early church patriarchal teaching (such as the Trinity), and while they hold to good Greek NT manuscripts, we should not accept a multitude of other teachings and practices which are unbiblical. You should also be aware that this church has formally condemned Calvinism in church statutes. The answer to the question, ‘ How Orthodox is the Eastern Orthodox Church? ’ is simply, ‘ Not very; in fact it is downright heretical in doctrine and practice ’. Here are the reasons why; but first I will give a potted history of the Orthodox Church. History What is the EOC? The Orthodox Church, or the Eastern Orthodox Church, 2 is a federation of Churches originating in the Greek-speaking Church of the Byzantine Empire, which reject the authority of the Roman Pope. It has the Patriarch of Constantinople 3 as its head and uses elaborate and archaic rituals. It calls itself, ‘The Holy Orthodox Catholic and Apostolic Church’. I will try to make this very complicated history as simple as I can. The history is also hindered by different sources contradicting each other and making mistakes of fact. Pre Chalcedon (to 451) The initial foundations of Greek theology were laid down by the Greek Fathers, such as Athanasius, John Chrysostom, Cyril of Alexandria, and the Cappadocian Fathers (the ‘Three Hierarchs’) i.e. -

The Concept of Energy in T. F. Torrance and in Orthodox Theology

THE CONCEPT OF ENERGY IN T. F. TORRANCE AND IN ORTHODOX THEOLOGY Stoyan Tanev, PhD Associate Professor, Department of Technology & Innovation, University of Southern Denmark, Odense, Denmark; Adjunct Professor, Faculty of Theology, nieity o Sof lgi Co-founder, International Center for Theologicl Scientifc lte [email protected] Abstract: The motivation for this paper is fourfold: (1) to emphasize the fact that the teaching on the distinction between Divine essence and energies is an integral part of Orthodox theology; (2) to provide an analysis of why Torrance did not adhere to it; (3) to correct certain erroneous perceptions regarding Orthodox theology put forward by scholars who have already discussed Torrance’s view on the essence-energies distinction in its relation to eication or theosis an nall to suggest an analsis emonstrating the correlation between Torrance’s engagements with particular themes in modern physics and the content of his theological positions. This last analsis is mae comparing his scientic theological approach to the approach of Christos Yannaras. The comparison provides an opportunity to emonstrate the correlation etween their preoccupations with specic themes in moern phsics an their specic theological insights. Thomas Torrance has clearly neglected the epistemological insights emerging from the advances of quantum mechanics in the 20th century and has ended up neglecting the value of the Orthodox teaching on the distinction between Divine essence and energies. This neglect seems to be associated with his specic prehalceonian unerstaning of personprosoponhpostasis. s a result he has expressed opinions that contradict the apophatic character of the distinction between Divine essence and energies and the subtlety of the apophatic realism of iinehuman communion. -

The Synod Process

The Synod Process I Convocation and Preparation of the Synod 2 Preparatory Commission 1 The bishop convenes the synod with the consultation of the • Members of the preparatory commission are chosen by the bishop. Presbyteral Council. • The preparatory commission assists the bishop in organizing and preparing for the synod. • The bishop establishes a synodal secretariat and possibly a press office. 1 2 4 Preparatory phases of synod • Spiritual, catechetical and formational preparation 4 1. All are invited to pray for the ongoing intention of the synod and its results, that it might become an authentic 3 event of grace for the Church. 3 Publication of the Synodal 2. All should be informed on the nature and Directory purpose of the synod and the scope of its The Synodal Directory includes: deliberations. 1. composition of the synod; • Diocesan Consultation 2. norms by which elections of synodal members are to be conducted; 1. The faithful and the clergy of the Diocese 3. various offices to be exercised by the synod; are encouraged to express their needs, 4. procedural norms of the synod meetings. desires, challenges and opinions regarding the synod topics. 2. Meetings will take place at each parish, then deanery, to discuss synod topics. II Conducting the Synod • Determining the questions 1. The bishop determines the • The actual synod consists of the synodal sessions, questions on which the synodal typically in the cathedral. debate will concentrate. • Members of the synod make the profession of the faith before commencing synodal discussions. • Themes to be examined are introduced from a brief report; discussion begins.