Final Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GOVT-PUNJAB Waitinglist Nphs.Pdf

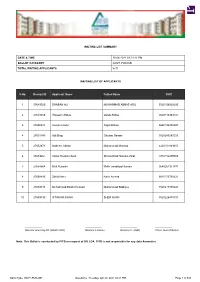

WAITING LIST SUMMARY DATE & TIME 20-04-2021 02:21:11 PM BALLOT CATEGORY GOVT-PUNJAB TOTAL WAITING APPLICANTS 8711 WAITING LIST OF APPLICANTS S No. Receipt ID Applicant Name Father Name CNIC 1 27649520 SHABAN ALI MUHAMMAD ABBAS ADIL 3520106922295 2 27649658 Waseem Abbas Qalab Abbas 3520113383737 3 27650644 Usman Hiader Sajid Abbasi 3650156358657 4 27651140 Adil Baig Ghulam Sarwar 3520240247205 5 27652673 Nadeem Akhtar Muhammad Mumtaz 4220101849351 6 27653461 Imtiaz Hussain Zaidi Shasmshad Hussain Zaidi 3110116479593 7 27654564 Bilal Hussain Malik tasadduq Hussain 3640261377911 8 27658485 Zahid Nazir Nazir Ahmed 3540173750321 9 27659188 Muhammad Bashir Hussain Muhammad Siddique 3520219305241 10 27659190 IFTIKHAR KHAN SHER KHAN 3520226475101 ------------------- ------------------- ------------------- ------------------- Director Housing-XII (LDAC NPA) Director Finance Director IT (I&O) Chief Town Planner Note: This Ballot is conducted by PITB on request of DG LDA. PITB is not responsible for any data Anomalies. Ballot Type: GOVT-PUNJAB Date&time : Tuesday, Apr 20, 2021 02:21 PM Page 1 of 545 WAITING LIST OF APPLICANTS S No. Receipt ID Applicant Name Father Name CNIC 11 27659898 Maqbool Ahmad Muhammad Anar Khan 3440105267405 12 27660478 Imran Yasin Muhammad Yasin 3540219620181 13 27661528 MIAN AZIZ UR REHMAN MUHAMMAD ANWAR 3520225181377 14 27664375 HINA SHAHZAD MUHAMMAD SHAHZAD ARIF 3520240001944 15 27664446 SAIRA JABEEN RAZA ALI 3110205697908 16 27664597 Maded Ali Muhammad Boota 3530223352053 17 27664664 Muhammad Imran MUHAMMAD ANWAR 3520223937489 -

Download Map (PDF | 4.45

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Overview - PUNJAB ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! K.P. ! ! ! ! ! ! Murree ! Tehsil ! ! ! ! ! ! Hasan Abdal Tehsil ! Attock Tehsil ! Kotli Sattian Tehsil ! Taxila Tehsil ! ! ! ! ! ! Attock ! ! ! ! Jand Tehsil ! Kahuta ! Fateh Jang Tehsil Tehsil ! ! ! Rawalpindi Tehsil ! ! ! Rawalpindi ! ! Pindi Gheb Tehsil ! J A M M U A N D K A S H M I R ! ! ! ! Gujar Khan Tehsil ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Sohawa ! Tehsil ! ! ! A F G H A N I S T A N Chakwal Chakwal ! ! ! Tehsil Sarai Alamgir Tehsil ! ! Tala Gang Tehsil Jhelum Tehsil ! Isakhel Tehsil ! Jhelum ! ! ! Choa Saidan Shah Tehsil Kharian Tehsil Gujrat Mianwali Tehsil Mianwali Gujrat Tehsil Pind Dadan Khan Tehsil Sialkot Tehsil Mandi Bahauddin Tehsil Malakwal Tehsil Phalia Mandi Bahauddin Tehsil Sialkot Daska Tehsil Khushab Piplan Tehsil Tehsil Wazirabad Tehsil Pasrur Tehsil Narowal Shakargarh Tehsil Shahpur Tehsil Khushab Gujranwala Bhalwal Hafizabad Tehsil Gujranwala Tehsil Tehsil Narowal Tehsil Sargodha Kamoke Tehsil Kalur Kot Tehsil Sargodha Tehsil Hafizabad Nowshera Virkan Tehsil Pindi Bhattian Tehsil Noorpur Sahiwal Tehsil Tehsil Darya Khan Tehsil Sillanwali Tehsil Ferozewala Tehsil Safdarabad Tehsil Sheikhupura Tehsil Chiniot -

High Court of Sindh, Karachi Tentative List of Applicants Applied for the Post of Civil Judge & Judicial Magistrate, 2020

HIGH COURT OF SINDH, KARACHI TENTATIVE LIST OF APPLICANTS APPLIED FOR THE POST OF CIVIL JUDGE & JUDICIAL MAGISTRATE, 2020 SNO NAME BIRTH DATE ENROL. DATE DOMICILE AND PRC OBJECTIONS REMARKS 1 Aadil Khan 17-MAR-1986 26-MAR-2016 Larkana - Eligible S/o Lal Bakhsh Narejo (34 years and 14 days) (4 years and 5 days) Larkana (20201824) 2 Aadil Khursheed 11-FEB-1992 22-JAN-2018 Shikarpur - Eligible S/o Khursheed Ahmed (28 years, 1 month and (2 years, 2 months and 9 days) Shikarpur BACHELOR DEGREE INSTEAD OF (20201873) 20 days) PASS CERTIFICATE IS REQUIRED. 3 Aajid Ali 08-APR-1992 07-JUL-2020 Sukkur - Not Eligible, Sub Court Enrollment Is S/o Mohammad Sabal (27 years, 11 months (No experience) Sukkur After Due Date (20202551) and 23 days) LL.B. DEGREE INSTEAD OF PASS CERTIFICATE AND BACHELORS DEGREE INSTEAD OF MARKS SHEET REQUIRED. 4 Aajiz Hussain Solangi 01-JAN-1989 01-AUG-2015 Naushero Feroze - Eligible S/o Mohammad Juman Solangi (31 years, 2 months and (4 years, 7 months and 30 days) Naushero Feroze (20201109) 30 days) 5 Aakash Kumar 14-APR-1992 25-MAY-2017 Karachi - Eligible, S/o Chandur Lal (27 years, 11 months (2 years, 10 months and 6 days) Karachi ASSISTANT SUPERINTENDENT in (20201837) and 17 days) HOME DEPARTMENT Appointment Date:11/02/2020 6 Aakash Kumar 17-AUG-1994 09-FEB-2019 Kamber @Shadadkot - Eligible S/o Anand Ram Sairani (25 years, 7 months and (1 year, 1 month and 22 days) Kamber @Shadadkot (20201692) 14 days) 7 Aakash Lal 15-SEP-1991 26-MAY-2018 Larkana - Eligible S/o Manohar Lal Mangrio (28 years, 6 months and (1 year, 10 months and 5 days) Larkana LL.B. -

District T.T.SINGH CRITERIA for RESULT of GRADE 8

Notes, Books, Past Papers, Test Series, Guess Papers & Many More Pakistan's Educational Network - SEDiNFO.NET - StudyNowPK.com - EduWorldPK.com District T.T.SINGH CRITERIA FOR RESULT OF GRADE 8 Criteria T.T.SINGH Punjab Status Minimum 33% marks in all subjects 88.34% 87.33% PASS Pass + Minimum 33% marks in four subjects and 28 to 32 marks Pass + Pass with 89.85% 89.08% in one subject Grace Marks Pass + Pass with Pass + Pass with grace marks + Minimum 33% marks in four Grace Marks + 97.79% 96.66% subjects and 10 to 27 marks in one subject Promoted to Next Class Candidate scoring minimum 33% marks in all subjects will be considered "Pass" One star (*) on total marks indicates that the candidate has passed with grace marks. Two stars (**) on total marks indicate that the candidate is promoted to next class. WWW.SEDiNFO.NET Notes, Books, Past Papers, Test Series, Guess Papers & Many More Pakistan's Educational Network - SEDiNFO.NET - StudyNowPK.com - EduWorldPK.com Notes, Books, Past Papers, Test Series, Guess Papers & Many More Pakistan's Educational Network - SEDiNFO.NET - StudyNowPK.com - EduWorldPK.com PUNJAB EXAMINATION COMMISSION, RESULT INFORMATION GRADE 8 EXAMINATION, 2020 DISTRICT: T.T.SINGH Students Students Students Pass % with Pass + Promoted Pass + Gender Registered Appeared Pass 33% marks Students Promoted % Male 11415 11145 9701 87.04 10907 97.86 Public School Female 12170 11963 10654 89.06 11692 97.73 Male 2576 2502 2266 90.57 2465 98.52 Private School Female 2188 2155 2002 92.90 2125 98.61 Male 596 570 434 76.14 529 92.81 -

People's Perceptıon Regardıng Jırga in Pakhtun Socıety

J. Appl. Environ. Biol. Sci. , 8(1)180-183, 2018 ISSN: 2090-4274 Journal of Applied Environmental © 2018, TextRoad Publication and Biological Sciences www.textroad.com People’s Perceptıon Regardıng Jırga ın Pakhtun Socıety Muhammad Nisar* 1, Anas Baryal 1, Dilkash Sapna 1, Zia Ur Rahman 2 Department of Sociology and Gender Studies, Bacha Khan University, Charsadda, KP, Pakistan 1 Department of Computer Science, Bacha Khan University, Charsadda, KP, Pakistan 2 Received: September 21, 2017 Accepted: December 11, 2017 ABSTRACT “This paper examines the institution of Jirga, and to assess the perceptions of the people regarding Jirga in District Malakand Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. A sample of 12 respondents was taken through convenience sampling method. In-depth interview was used as a tool for the collection of data from the respondents. The results show that Jirga is deep rooted in Pashtun society. People cannot go to courts for the solution of every problem and put their issues before Jirga. Jirga in these days is not a free institution and cannot enjoy its power as it used to be in the past. The majorities of Jirgaees (Jirga members) are illiterate, cannot probe the cases well, cannot enjoy their free status as well as take bribes and give their decisions in favour of wealthy or influential party. The decisions of Jirgas are not fully based on justice, as in many cases it violates the human rights. Most disadvantageous people like women and minorities are not given representation in Jirga. The modern days legal justice system or courts are exerting pressure on Jirga and declare it as illegal. -

Marks and 4 Credits

DHAKA UNIVERSITY AFFILIATED COLLEGES Syllabus Department of Islamic Studies One Year M.A. (Final) Course Effective from the Session: 2016-2017 to 2020-2021 1 M. A. in Islamic Studies in the colleges affiliated with the UNIVERSITY OF DHAKA is one year programme. Students are required to complete seven courses and one term paper (2 Credits) + Viva Voce (2 Credits) = 4 Credits. Each course will carry 100 marks and 4 credits. Students are required to obtain at least D grade (40 to less than 45 marks) for M.A degree. There will be one In-course test, one class attendance evaluation and a Course Final Examination at the end of the year for each course. Distribution of marks is as follows: Marks distribution for each course is as follows: 1. One In-Course Test of 15 marks: 15 marks 2. Class Attendance and Participation: 5 marks 3. Course Final Examination of 4 hours duration : 80 marks Total Marks : 100 Total Classes : 60 Total hours : 60 Total Credit Hours : 4 Explanations:- Evaluation of a courses of 100 marks: a. Each course will be taught by the Department and evaluated by one teacher from DU or affiliated colleges. Marks Distribution for each course: a. One In-course Test of 15 marks:15 Marks One test of one hour duration to be given by each course teacher at his/her convenience. b. Class Attendance and Participation: 5 Marks Each teacher will give marks out of 5. A single teacher teaching a course will give marks out of 5. c. Course Final Examination of 4 hours duration: 5x16= 80 Marks Two teachers will set questions and one teacher will evaluate the scripts. -

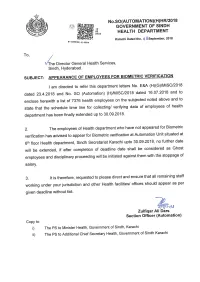

Pending Biometric) Non-Verified Unknown District S.No Employee Name Father Name Designation Institution Name CNIC Personel ID

Details of Employees (Pending Biometric) Non-Verified Unknown District S.no Employee Name Father Name Designation Institution Name CNIC Personel ID Women Medical 1 Dr. Afroze Khan Muhammad Chang (NULL) (NULL) Officer Women Medical 2 Dr. Shahnaz Abdullah Memon (NULL) 4130137928800 (NULL) Officer Muhammad Yaqoob Lund Women Medical 3 Dr. Saira Parveen (NULL) 4130379142244 (NULL) Baloch Officer Women Medical 4 Dr. Sharmeen Ashfaque Ashfaque Ahmed (NULL) 4140586538660 (NULL) Officer 5 Sameera Haider Ali Haider Jalbani Counselor (NULL) 4230152125668 214483656 Women Medical 6 Dr. Kanwal Gul Pirbho Mal Tarbani (NULL) 4320303150438 (NULL) Officer Women Medical 7 Dr. Saiqa Parveen Nizamuddin Khoso (NULL) 432068166602- (NULL) Officer Tertiary Care Manager 8 Faiz Ali Mangi Muhammad Achar (NULL) 4330213367251 214483652 /Medical Officer Women Medical 9 Dr. Kaneez Kalsoom Ghulam Hussain Dobal (NULL) 4410190742003 (NULL) Officer Women Medical 10 Dr. Sheeza Khan Muhammad Shahid Khan Pathan (NULL) 4420445717090 (NULL) Officer Women Medical 11 Dr. Rukhsana Khatoon Muhammad Alam Metlo (NULL) 4520492840334 (NULL) Officer Women Medical 12 Dr. Andleeb Liaqat Ali Arain (NULL) 454023016900 (NULL) Officer Badin S.no Employee Name Father Name Designation Institution Name CNIC Personel ID 1 MUHAMMAD SHAFI ABDULLAH WATER MAN unknown 1350353237435 10334485 2 IQBAL AHMED MEMON ALI MUHMMED MEMON Senior Medical Officer unknown 4110101265785 10337156 3 MENZOOR AHMED ABDUL REHAMN MEMON Medical Officer unknown 4110101388725 10337138 4 ALLAH BUX ABDUL KARIM Dispensor unknown -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Here, There, and Elsewhere: A Multicentered Relational Framework for Immigrant Identity Formation Based on Global Geopolitical Contexts Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5817t513 Author Shams, Tahseen Publication Date 2018 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Here, There, and Elsewhere: A Multicentered Relational Framework for Immigrant Identity Formation Based on Global Geopolitical Contexts A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology by Tahseen Shams 2018 © Copyright by Tahseen Shams 2018 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Here, There, and Elsewhere: A Multicentered Relational Framework for Immigrant Identity Formation Based on Global Geopolitical Contexts by Tahseen Shams Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology University of California, Los Angeles, 2018 Professor Roger Waldinger, Co-Chair Professor Rubén Hernández-León, Co-Chair The scholarship on international migration has long theorized how immigrants form new identities and build communities in the hostland. However, largely limited to studying the dyadic ties between the immigrant-sending and -receiving countries, research thus far has overlooked how sociopolitics in places beyond, but in relation to, the homeland and hostland can also shape immigrants’ identities. This dissertation addresses this gap by introducing a more comprehensive analytical design—the multicentered relational framework—that encompasses global political contexts in the immigrants’ homeland, hostland, and “elsewhere.” Based primarily on sixty interviews and a year’s worth of ethnographic data on Pakistani, Bangladeshi, and Indian Muslims in California, I trace how different dimensions of the immigrants’ “Muslim” identity category tie them to different “elsewhere” contexts. -

Mufti.Ebrahim.Desai

IMĀM BUKHĀRI Rahmatullahi alayhi and his famous Al-Jāmi Al- Sahīh By MUFTI EBRAHIM DESAI Hafidhahullah Published By: Darul Iftaa Mahmudiyyah www.daruliftaa.net Tel +27 31 271 3338 Websites www.daruliftaa.net | www.askimam.org www.idealwoman.org | www.darulmahmood.net Twitter @Darul_iftaa | @MuftiEbrahim © 2020 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by an information storage and retrieval system without permission from the publisher. # In the Name of Allah, the Most Gracious, the Most Merciful o _______________ III _______________ 1 _ NAME The full name of Imām Bukhāri (Rahmatullahi Alayh) was; Abu Abdullāh Muhammad ibn Ismaīl ibn Ibrahīm ibn Mughīra ibn Bardizba Al Ju’fī Al Bukhārī. _______________ III _______________ 2 _ BIRTH AND LINEAGE Imām Bukhāri was born on Friday (after Jumuah), on the 13th of Shawwāl, 194H. He was born blind. His mother would make excessive duā for him until one night she saw the Prophet Ibrahīm (alayhi salām) in her dream. The Prophet Ibrahīm (alayhi salām) gave her glad tidings that Allah had restored her son’s eyesight because of her excessive duā. Imām Bukhāri passed away on Friday, the 1st of Shawwāl, 256 H (the night before Eid al-Fitr). (Al-Hady al-Sāri – pg.477). Bardizba, the ancestor of Imām Bukhāri was a fire worshipper. In Bukhāra, Bardizba meant a farmer. Mawlānā Badr-e-Alam Sāhib stated that he met a Russian alim who pronounced it as Bardazba and he said that it means an expert. -

The Constitution and Female-Initiated Divorce in Pakistan: Western Liberalism in Islamic Garb

\\jciprod01\productn\H\HLG\34-2\HLG207.txt unknown Seq: 1 13-JUN-11 8:12 THE CONSTITUTION AND FEMALE-INITIATED DIVORCE IN PAKISTAN: WESTERN LIBERALISM IN ISLAMIC GARB KARIN CARMIT YEFET* “[N]o nation can ever be worthy of its existence that cannot take its women along with the men.” Mohammad Ali Jinnah, Founder of Pakistan1 The legal status of Muslim women, especially in family relations, has been the subject of considerable international academic and media interest. This Article examines the legal regulation of di- vorce in Pakistan, with particular attention to the impact of the nation’s dual constitutional commitments to gender equality and Islamic law. It identifies the right to marital freedom as a constitu- tional right in Pakistan and demonstrates that in a country in which women’s rights are notoriously and brutally violated, female di- vorce rights stand as a ray of light amidst the “darkness” of the general legal status of Pakistani women. Contrary to the conven- tional wisdom construing Islamic law as opposed to women’s rights, the constitutionalization of Islam in Pakistan has proven to be a potent tool in the service of women’s interests. Ultimately, I hope that this Article may serve as a model for the utilization of both Islamic and constitutional law to benefit women throughout the Muslim world. Introduction .................................................... 554 R I. All-or-Nothing: Classical Islam’s Gendered Divorce Regime ................................................. 557 R A. The Husband’s Right to Untie the Knot ............... 558 R * I wish to express my deep gratitude to Professors Akhil Reed Amar and Reva Siegel for their thoughtful and inspiring comments. -

Ethnographic Series, Sidhi, Part IV-B, No-1, Vol-V

CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 VOLUMEV, PART IV-B, No.1 ETHNOGRAPHIC SERIES GUJARAT Preliminary R. M. V ANKANI, investigation Tabulation Officer, and draft: Office of the CensuS Superintendent, Gujarat. SID I Supplementary V. A. DHAGIA, A NEGROID L IBE investigation: Tabulation Officer, Office of the Census Superintendent, OF GU ARAT Gujarat. M. L. SAH, Jr. Investigator, Office of the Registrar General, India. Fieta guidance, N. G. NAG, supervision and Research Officer, revised draft: Office of the Registrar General, India. Editors: R. K. TRIVEDI, Su perintendent of Census Operations, Gujarat. B. K. Roy BURMAN, Officer on Special Duty, (Handicrafts and Social Studies), Office of the Registrar General, India. K. F. PATEL, R. K. TRIVEDI Deputy Superintendent of Census Superintendent of Census Operations, Gujarat. Operations, Gujarat N. G. NAG, Research Officer, Office' of the Registrar General, India. CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 LIST OF PUBLICATIONS CENTRAL GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS Census of India, 1961 Volume V-Gujarat is being published in the following parts: '" I-A(i) General Report '" I-A(ii)a " '" I-A(ii)b " '" I-A(iii) General Report-Economic Trends and Projections :« I-B Report on Vital Statistics and Fertility Survey :I' I-C Subsidiary Tables '" II-A General Population Tables '" II-B(I) General Economic Tables (Tables B-1 to B-IV-C) '" II-B(2) General Economic Tables (Tables B-V to B-IX) '" II-C Cultural and Migration Tables :t< III Household Economic Tables (Tables B-X to B-XVII) "'IV-A Report on Housing and Establishments :t<IV-B Housing and Establishment -

Electoral Politics in Pakistan: a Case Study of NA-94 Abstract

Abdul Qadir Mushtaq1 Muhammad Ibrahim2 Electoral Politics In Pakistan: A Case Study of NA-94 Abstract: This constituency consists of Kamalia, Pirmahal and its sournding villages. Before 1985 elections, it was the part of district Faisalabad but before 1985, Zia regime decided to establish new district Toba Tek Singh. Kamalia is the Tehsil head quater of T. T. singh but its area has been divided into two constituencies. Few villages fall in NA and other villages are situated in NA. 94. The major bridaries of this constituency are, Syed, Arian, Jutt, Rajput, Rajput Bhatti, Kharals, Fityyana. Before 1985, the main leadership was in the hands of Syeds. Two different groups existed among them; one was leading Syed Nasir Deen Shah and second was under the control of Makhdoom Nazir Deen shah. These two groups ruled over district council Faisalabad for many years. Zia regime tried to dismental its influence and decided to divide the follwers of these two groups onto different districts. Few villages of their followers had been given in district Jaranwala, few were given in district Faisalabad and few came in the vicinity of district Toba Teksingh. In this way, the power of the Syed family came to an end. Now in the existing set up, the leadership is in the hands of three major families i.e. Syed, Arian and Fatiana. This paper presents the historical background of the electoral politics and role of bradrise in the victory of the candidates. Introduction Kamalia is a Tehsil of Toba Tek Singh District which is situated in Punjab, Pakistan.