King John and the Cistercians in Wales

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Antiphonary of Bangor and Its Musical Implications

The Antiphonary of Bangor and its Musical Implications by Helen Patterson A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Music University of Toronto © Copyright by Helen Patterson 2013 The Antiphonary of Bangor and its Musical Implications Helen Patterson Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Music University of Toronto 2013 Abstract This dissertation examines the hymns of the Antiphonary of Bangor (AB) (Antiphonarium Benchorense, Milan, Biblioteca Ambrosiana C. 5 inf.) and considers its musical implications in medieval Ireland. Neither an antiphonary in the true sense, with chants and verses for the Office, nor a book with the complete texts for the liturgy, the AB is a unique Irish manuscript. Dated from the late seventh-century, the AB is a collection of Latin hymns, prayers and texts attributed to the monastic community of Bangor in Northern Ireland. Given the scarcity of information pertaining to music in early Ireland, the AB is invaluable for its literary insights. Studied by liturgical, medieval, and Celtic scholars, and acknowledged as one of the few surviving sources of the Irish church, the manuscript reflects the influence of the wider Christian world. The hymns in particular show that this form of poetical expression was significant in early Christian Ireland and have made a contribution to the corpus of Latin literature. Prompted by an earlier hypothesis that the AB was a type of choirbook, the chapters move from these texts to consider the monastery of Bangor and the cultural context from which the manuscript emerges. As the Irish peregrini are known to have had an impact on the continent, and the AB was recovered in ii Bobbio, Italy, it is important to recognize the hymns not only in terms of monastic development, but what they reveal about music. -

Tavistock Abbey

TAVISTOCK ABBEY Tavistock Abbey, also known as the Abbey of Saint Mary and Saint Rumon was originally constructed of timber in 974AD but 16 years later the Vikings looted the abbey then burned it to the ground, the later abbey which is depicted here, was then re-built in stone. On the left is a 19th century engraving of the Court Gate as seen at the top of the sketch above and which of course can still be seen today near Tavistock’s museum. In those early days Tavistock would have been just a small hamlet so the abbey situated beside the River Tavy is sure to have dominated the landscape with a few scattered farmsteads and open grassland all around, West Down, Whitchurch Down and even Roborough Down would have had no roads, railways or canals dividing the land, just rough packhorse routes. There would however have been rivers meandering through the countryside of West Devon such as the Tavy and the Walkham but the land belonging to Tavistock’s abbots stretched as far as the River Tamar; packhorse routes would then have carried the black-robed monks across the border into Cornwall. So for centuries, religious life went on in the abbey until the 16th century when Henry VIII decided he wanted a divorce which was against the teachings of the Catholic Church. We all know what happened next of course, the Dissolution of the Monasteries, when along with all the other abbeys throughout the land, Tavistock Abbey was raised to the ground. Just a few ruined bits still remain into the 21st century. -

LLYWELYN TOUR Builth Castle, SO 043511

Return to Aberedw and follow the road to Builth Wells Ffynnon Llywelyn is reached by descending the LLYWELYN TOUR Builth Castle, SO 043511. LD2 3EG This is steps at the western end of the memorial. Tradition has A Self Drive Tour to visit the reached by a footpath from the Lion Hotel, at the south- it that Llywelyn's head was washed here before being places connected with the death ern end of the Wye Bridge. There are the remains of a taken to the king at Rhuddlan. of Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, sophisticated and expensive castle, rebuilt by Edward in Take the A483 back to Builth and then northwards Prince of Wales 1256 – 1282 1277. John Giffard was Constable of the castle in 1282 through Llandrindod and Crossgates. 2 miles north of and host to Roger le Strange, the commander of the this turn left for Abbey Cwmhir LD1 6PH. In the cen- King's squadron and Edmund Mortimer. INTRODUCTION tre of the village park in the area provided at Home Farm and walk down past the farmhouse to the ruins of Where was he killed? There are two very different the abbey. accounts of how Llywelyn died. The one most widely Llywelyn Memorial Stone SO 056712. This was accepted in outline by many English historians is that of Walter of Guisborough, written eighteen years after the placed in the ruins in 1978 near the spot where the grave is thought to lie. In 1876 English Court Records event, at the time of the crowning of the first English Prince of Wales in 1301. -

Accounts of the Constables of Bristol Castle

BRISTOL RECORD SOCIETY'S PUBLICATIONS General Editor: PROFESSOR PATRICK MCGRATH, M.A., Assistant General Editor: MISS ELIZABETH RALPH, M .A., F.S.A. VOL. XXXIV ACCOUNTS OF THE CONSTABLES OF BRISTOL CASTLE IN 1HE THIRTEENTH AND EARLY FOURTEENTH CENTURIES ACCOUNTS OF THE CONSTABLES OF BRISTOL CASTLE IN THE THIR1EENTH AND EARLY FOUR1EENTH CENTURIES EDITED BY MARGARET SHARP Printed for the BRISTOL RECORD SOCIETY 1982 ISSN 0305-8730 © Margaret Sharp Produced for the Society by A1an Sutton Publishing Limited, Gloucester Printed in Great Britain by Redwood Burn Limited Trowbridge CONTENTS Page Abbreviations VI Preface XI Introduction Xlll Pandulf- 1221-24 1 Ralph de Wiliton - 1224-25 5 Burgesses of Bristol - 1224-25 8 Peter de la Mare - 1282-84 10 Peter de la Mare - 1289-91 22 Nicholas Fermbaud - 1294-96 28 Nicholas Fermbaud- 1300-1303 47 Appendix 1 - Lists of Lords of Castle 69 Appendix 2 - Lists of Constables 77 Appendix 3 - Dating 94 Bibliography 97 Index 111 ABBREVIATIONS Abbrev. Plac. Placitorum in domo Capitulari Westmon asteriensi asservatorum abbrevatio ... Ed. W. Dlingworth. Rec. Comm. London, 1811. Ann. Mon. Annales monastici Ed. H.R. Luard. 5v. (R S xxxvi) London, 1864-69. BBC British Borough Charters, 1216-1307. Ed. A. Ballard and J. Tait. 3v. Cambridge 1913-43. BOAS Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society Transactions (Author's name and the volume number quoted. Full details in bibliography). BIHR Bulletin of the Institute of Historical Research. BM British Museum - Now British Library. Book of Fees Liber Feodorum: the Book of Fees com monly called Testa de Nevill 3v. HMSO 1920-31. Book of Seals Sir Christopher Hatton's Book of Seals Ed. -

King John's Tax Innovation -- Extortion, Resistance, and the Establishment of the Principle of Taxation by Consent Jane Frecknall Hughes

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by eGrove (Univ. of Mississippi) Accounting Historians Journal Volume 34 Article 4 Issue 2 December 2007 2007 King John's tax innovation -- Extortion, resistance, and the establishment of the principle of taxation by consent Jane Frecknall Hughes Lynne Oats Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/aah_journal Part of the Accounting Commons, and the Taxation Commons Recommended Citation Hughes, Jane Frecknall and Oats, Lynne (2007) "King John's tax innovation -- Extortion, resistance, and the establishment of the principle of taxation by consent," Accounting Historians Journal: Vol. 34 : Iss. 2 , Article 4. Available at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/aah_journal/vol34/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Archival Digital Accounting Collection at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Accounting Historians Journal by an authorized editor of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Hughes and Oats: King John's tax innovation -- Extortion, resistance, and the establishment of the principle of taxation by consent Accounting Historians Journal Vol. 34 No. 2 December 2007 pp. 75-107 Jane Frecknall Hughes SHEFFIELD UNIVERSITY MANAGEMENT SCHOOL and Lynne Oats UNIVERSITY OF WARWICK KING JOHN’S TAX INNOVATIONS – EXTORTION, RESISTANCE, AND THE ESTABLISHMENT OF THE PRINCIPLE OF TAXATION BY CONSENT Abstract: The purpose of this paper is to present a re-evaluation of the reign of England’s King John (1199–1216) from a fiscal perspective. The paper seeks to explain John’s innovations in terms of widening the scope and severity of tax assessment and revenue collection. -

Between History & Hope: Where Will the Church Be in 2020?

www.stdavidsdiocese.org.uk Tachwedd / November 2010 ‘Something Must be Done!’ ORD Rowe-Beddoe, the At the September meeting of the Governing Body of the Church in Wales, members ute to the growth of the churches.” LChairman of the Representa- were given a succinct and honest account of the state of the Church’s finances and It is interesting that the two tive Body (RB), the organisation future predictions. Paul Mackness reports people presenting that report were that administers the Church in both lay people, Richard Jones, Wales’ finances, summed up the punch: “ . your fund is in pretty the Parish Resources Adviser for current problems, “The financial good shape – but we do not see a It is inevitable Llandaff Diocese, and Tracey situation of the Church in Wales substantial uplift in the medium that clergy feel White, Funding and Parish Support is unlikely to improve over the term. Meanwhile the costs of the de-motivated when officer for St Asaph Diocese. next five years and will be unable Church rise inexorably. Something The questions posed dominated to continue operating in the way has to be done!” they service numerous the rest of the the meeting. it is doing at the moment. Never- The Church, like the secular congregations without Is it now time for change? Has theless the objectives of the RB world, is going to have to tighten the parish system run its course? remain – to relieve financial pres- its belt if we are to survive. For the opportunity to What needs to change in order for sure on parishes and support the past three years -

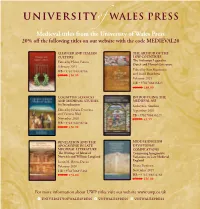

Medieval Titles from the University of Wales Press 20% Off the Following Titles on Our Website with the Code MEDIEVAL20

Medieval titles from the University of Wales Press 20% off the following titles on our website with the code MEDIEVAL20 CHAUCER AND ITALIAN THE ARTHUR OF THE CULTURE LOW COUNTRIES The Arthurian Legend in Edited by Helen Fulton Dutch and Flemish Literature February 2021 HB • 9781786836786 Edited by Bart Besamusca £70.00 £56.00 and Frank Brandsma February 2021 HB • 9781786836823 £80.00 £64.00 COGNITIVE SCIENCES INTRODUCING THE AND MEDIEVAL STUDIES MEDIEVAL ASS An Introduction Kathryn L. Smithies Edited by Juliana Dresvina September 2020 and Victoria Blud PB • 9781786836229 November 2020 £11.99 £9.59 HB • 9781786836748 £70.00 £56.00 REVELATION AND THE MIDDLE ENGLISH APOCALYPSE IN LATE DEVOTIONAL MEDIEVAL LITERATURE COMPILATIONS The Writings of Julian of Composing Imaginative Norwich and William Langland Variations in Late Medieval Justin M. Byron-Davies England February 2020 Diana Denissen HB • 9781786835161 November 2019 £70.00 £56.00 HB • 9781786834768 £70.00 £56.00 For more information about UWP titles visit our website www.uwp.co.uk B UNIVERSITYOFWALESPRESS A UNIWALESPRESS V UNIWALESPRESS 20% OFF WITH THE CODE MEDIEVAL20 TRIOEDD YNYS PRYDEIN GEOFFREY OF MONMOUTH PRINCESSES OF WALES The Triads of the Island of Britain Karen Jankulak Deborah Fisher THE ECONOMY OF MEDIEVAL Edited by Rachel Bromwich PB • 9780708321515 £7.99 £4.00 PB • 9780708319369 £3.99 £2.00 WALES, 1067-1536 PB • 9781783163052 £24.99 £17.49 Matthew Frank Stevens GENDERING THE CRUSADES REVISITING THE MEDIEVAL PB • 9781786834843 £24.99 £19.99 THE WELSH AND Edited by Susan B. Edgington NORTH OF ENGLAND THE MEDIEVAL WORLD and Sarah Lambert Interdisciplinary Approaches INTRODUCING THE MEDIEVAL Travel, Migration and Exile PB • 9780708316986 £19.99 £10.00 Edited by Anita Auer, Denis Renevey, DRAGON Edited by Patricia Skinner Camille Marshall and Tino Oudesluijs Thomas Honegger HOLINESS AND MASCULINITY PB • 9781786831897 £29.99 £20.99 PB • 9781786833945 £35.00 £17.50 PB • 9781786834683 £11.99 £9.59 IN THE MIDDLE AGES 50% OFF WITH THE CODE MEDIEVAL50 Edited by P. -

Minutes of an Ordinary Meeting

Minutes of the Ordinary Meeting of Abbeydore and Bacton Group Parish Council held in Abbeydore Village Hall on Tuesday 3rd March 2020 No ABPC/MW/103 Present Councillor Mr D Watkins Chairman Councillor Mr T Murcott Vice - Chairman Councillor Mr D Bannister Councillor Mrs W Gunn Councillor Mr M Jenkins Clerk Mr M Walker Also Present PC Jeff Rouse, PCSO Pete Knight and one further member of the public The Parish Council Meeting was formally opened by the Chairman at 7.30pm 1.0 Apologies for Absence Apologies were received from Councillor Mrs A Booth, Councillor Mr D Cook, Councillor Mr R Fenton and Golden Valley South Ward Councillor Mr Peter Jinman Parish Lengthsman/Contractor Mr Terry Griffiths and Locality Steward Mr Paul Norris not present 2.0 Minutes The Minutes of the Ordinary Group Parish Council Meeting No ABPC/MW/102 held on th Tuesday 7 January 2020 were unanimously confirmed as a true record and signed by the Chairman 3.0 Declarations of Interest and Dispensations 3.1 To receive any declarations of interest in agenda items from Councillors No Declarations of Interest were made 3.2 To consider any written applications for dispensation There were no written applications for dispensation made The Parish Council resolved to change the order of business at this time to Item 7.2 7.0 To Receive Reports (if available) from:- 7.2 West Mercia Police PC Jeff Rouse Safer Neighbourhood Team reported on the following:- No recent thefts or burglaries on the patch Scams involving the elderly, vulnerable females e.g. -

The First Life of Bernard of Clairvaux

CISTERCIAN FATHERS SERIES: NUMBER SEVENTY-SIX THE FIRST LIFE OF BERNARD OF CLAIRVAUX CISTERCIAN FATHERS SERIES: NUMBER SEVENTY-SIX The First Life of Bernard of Clairvaux by William of Saint-Thierry, Arnold of Bonneval, and Geoffrey of Auxerre Translated by Hilary Costello, OCSO Cistercian Publications www.cistercianpublications.org LITURGICAL PRESS Collegeville, Minnesota www.litpress.org A Cistercian Publications title published by Liturgical Press Cistercian Publications Editorial Offices 161 Grosvenor Street Athens, Ohio 45701 www.cistercianpublications.org In the absence of a critical edition of Recension B of the Vita Prima Sancti Bernardi, this translation is based on Mount Saint Bernard MS 1, with section numbers inserted from the critical edition of Recension A (Vita Prima Sancti Bernardi Claraevallis Abbatis, Liber Primus, ed. Paul Verdeyen, CCCM 89B [Turnhout: Brepols Publishers, 2011]). Scripture texts in this work are translated by the translator of the text. The image of Saint Bernard on the cover is a miniature from Mount Saint Bernard Abbey, fol. 1, reprinted with permission from Mount Saint Bernard Abbey. © 2015 by Order of Saint Benedict, Collegeville, Minnesota. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by print, microfilm, microfiche, mechanical recording, photocopying, translation, or any other means, known or yet unknown, for any purpose except brief quotations in reviews, without the previous written permission of Liturgical Press, Saint John’s Abbey, PO Box 7500, College- ville, Minnesota 56321-7500. Printed in the United States of America. 123456789 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Vita prima Sancti Bernardi. English The first life of Bernard of Clairvaux / by William of Saint-Thierry, Arnold of Bonneval, and Geoffrey of Auxerre ; translated by Hilary Costello, OCSO. -

The Archaeological Record of the Cistercians in Ireland, 1142-1541

THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL RECORD OF THE CISTERCIANS IN IRELAND, 1142-1541 written by SIMON HAYTER October 2013 Abstract In the twelfth century the Christian Church experienced a revolution in its religious organisation and many new monastic Orders were founded. The Cistercian Order spread rapidly throughout Europe and when they arrived in Ireland they brought a new style of monasticism, land management and architecture. The Cistercian abbey had an ordered layout arranged around a cloister and their order and commonality was in sharp contrast to the informal arrangement of the earlier Irish monasteries. The Cistercian Order expected that each abbey must be self-sufficient and, wherever possible, be geographically remote. Their self-sufficiency depended on their land- holdings being divided into monastic farms, known as granges, which were managed by Cisterci and worked by agricultural labourers. This scheme of land management had been pioneered on the Continent but it was new to Ireland and the socio-economic impact on medieval Ireland was significant. Today the surviving Cistercian abbeys are attractive ruins but beyond the abbey complex and within the wider environment they are nearly invisible. Medieval monastic archaeology in Ireland, which in modern terms began in the 1950s, concentrated almost exclusively on the abbey complex. The dispersed monastic land-holdings, grange complexes and settlement patterns have been almost totally ignored. This report discusses the archaeological record produced through excavations of Cistercian sites, combined -

Maison De Verdun Barenton (Au Comté De Mortain) Sont De Possibles Berceaux De La Famille ; a Priori, Boucey (Près Pontorson), Est Une Possession Tardive (XV° S.)

Normandie (Avranchin, Mortanais), Angleterre (Staffordhire, Leicestershire, Buckinghamshire, Warwickshire, Derbyshire), Irlande Extraction chevaleresque : XI° siècle en Normandie maintenue en noblesse (1463 par Monfaut) Branches de Verdun de La Crenne, Ballant, Barenton et Passais - 1) La Crenne Guillaume 1423 ; maintenu noble 1599 et 1624 divisée en 2 branches : a) La Crenne maintenue noble en 1666 ; b) Ballant maintenu noble en 1671 - 2) Barenton et Passais Colin de Verdun 1410 Fougères maintenu noble en 1635 Saint-Martin-des-Champs & Saint-Quentin-sur-le-Homme (Avranchin) ; Maison de Verdun Barenton (au comté de Mortain) sont de possibles berceaux de la famille ; a priori, Boucey (près Pontorson), est une possession tardive (XV° s.). & Verdon/Vardon Armes : en Grande-Bretagne France : «D’or (alias d’argent) fretté de sable (de six pièces)» «D’Argent, fretté de sable, de six pièces» (d’Hozier Grande-Bretagne : «D’or fretté de gueules» Verdun, Verdon, Vardon Verdun (France) Devises : «Coeli Sub Rore Virescens» & «Levius Fit Patientia» (Grande-Bretagne) (Goldstone Hall) ; «Gratia Dei Sum Id Quod Sum» Support : lambrequins d’or & d’azur ou d’or & de gueules Cimier : tête de cerf (Goldstone) Sources complémentaires : Dictionnaire de la Noblesse (F. A. Aubert de La Chesnaye-Desbois, éd. 1775, Héraldique & Généalogie), "Grand Armorial de France" - Henri Jougla de Morenas & Raoul de Warren - Reprint Mémoires & Documents - 1948, tome 6, sites Roglo, Wikipedia, Geneawiki, de-verdon.uk, jcdeval06, Archives de la Manche (AD50), wappenwiki (House -

Fortgranite Estate

FORTGRANITE ESTATE COUNTY WICKLOW | IRELAND FORTGRANITE ESTATE BALTINGLASS | COUNTY WICKLOW | IRELAND | W91 W304 Carlow 26 km | Wicklow 54 km | Kilkenny 67 km | Dublin 71 km | Dublin Airport 77km (Distances are approximate) HISTORIC COUNTRY ESTATE FOR SALE FOR +353 (0)45 433 550 THE FIRST TIME IN ITS HISTORY Jordan Auctioneers Edward Street, Newbridge Co. Kildare W12 RW24 FORTGRANITE HOUSE [email protected] Ground Floor: Entrance hall | Drawing room | Library | Morning room | Dining room | Inner hall | Breakfast room [email protected] Pantry | Kitchen | Back hall | Cloakroom. www.jordancs.ie First Floor: 10 bedrooms | 4 bathrooms. Second Floor: Bedroom | School room. Lower Ground Floor: Former kitchen | Boiler room | Former larder | China room | Saddle room | Wine cellar Old workshop | Coal store | 4 further store rooms. +353 (0)16 342 466 TRADITIONAL COURTYARDS STEWARD’S HOUSE Knight Frank 20-21 Upper Pembroke Street 2 traditional ranges of beautiful granite buildings comprising Sitting room | Kitchen | 3 bedrooms | Bathroom Dublin 2 D02 V449 9 loose boxes and various stores. Store room | 2 WCs [email protected] [email protected] MODERN FARMYARD HERD’S COTTAGE Range of modern farm buildings and dairy. Entrance hall / dining area | Sitting room | Kitchen Store | 2 bedrooms | Bathroom. +44 (0)20 7861 1069 DOYLE’S LODGE Knight Frank - Country Department Parkland | Grassland and woodland including spectacular 55 Baker Street Sitting room | Kitchen | Bedroom | Bathroom | 2 stores. historic arboretum and mature gardens. London W1U 8AN [email protected] LENNON’S LODGE In all about 341 acres. [email protected] Sitting room | Kitchen | Bedroom | Bathroom | Store. For sale Freehold as a whole.